Making the Business Case for Packaging Reuse Systems Study - June 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Plastic Reusable Packaging?

Sustainability Advantages of Reusable Containers What is plastic reusable packaging? Plastic reusable packaging products are used to move, store and distribute product within a single operation or entire supply chain. From raw material to finished goods, plastic reusable packaging safely and efficiently moves material/product along different points of the supply chain and ultimately to its destination. It is ideal for multiple trip applications in a closed-loop environment or well-managed supply chain. It can also be used effectively in a managed open-loop system, with reverse logistics in place to return empty containers or pallets for re-use or replenishment. Products can include: • Hand-held containers, bins, boxes or totes • Pallets, slip sheets, top frames and top caps • Divider sheets • Bulk containers, bins, boxes or totes • Protective interior dunnage (custom) • Storage containers and metal systems • Custom designed and engineered packaging By design, plastic reusable packaging products offer durable, rigid construction; contoured surfaces; easy-to-grasp handles; high levels of recyclability and vast identification options. These dimensionally consistent containers and pallets are easy to handle and interface effortlessly with all types of high-speed automated equipment. In fact, some products are specially designed to be "hands-free" and solely handled by robots or conveyors. Plastic packaging has no nails or loose corrugated flaps to halt a high-speed system. And, in high-volume industries, hundreds of thousands of dollars are lost when an automated system is stopped. Whether shipping plastic bottles to a soft drink bottler for filling; trim parts to an automotive manufacturer; electronic components to a computer manufacturer or consumer goods to the mass retailer, plastic reusable containers and pallets will help move product faster, better, safer and more cost effectively. -

Using Plastic Reusable Packaging to Support Your Lean Operation

Lean Packaging: Using Plastic Reusable Packaging to Support Your Lean Operation Copyright ã2004 ORBIS Corporation Executive Overview Today, more than 33% of US companies recognize the need for a lean philosophy to gain optimization in their operations and entire supply chain. Very simply….the lean philosophy emphasizes total system efficiency, continual improvement and value-added activity, to reduce costs. 1 This can be achieved in three ways: § The aggressive elimination of waste § Improved productive flow of material/product § Highly optimized inventory management According to the March 2001 issue of Modern Materials Handling, “Businesses succeed or fail based on their supply chain performance, therefore, the scope of lean thinking must encompass every aspect of every job within a company, including factory operations, engineering, project management, transportation and finance.” 2 And this includes packaging. According to Ford Motor Company, plastic reusable packaging drives lean production by facilitating the tremendous benefits. It opens the door to better scheduling, smaller batches and inventories, faster response to schedule changes and smaller, more frequent deliveries leading to the success of their "Synchronous Material Flow." It facilitates improved layouts and processes and provides a cleaner, safer, more ergonomic workplace. The net effect drives costs down. 3 The concepts behind lean production are not industry-specific. Whether shipping plastic bottles to a soft drink bottler for filling; trim parts to an automotive manufacturer; electronic components to a computer manufacturer or consumer goods to the mass retailer, plastic reusable packaging will help move product faster, better, safer and more cost effectively. While lean production seems is prevalent in the automotive industry, plenty of other leading industries have adopted lean philosophies, including: beverage, electronics, aerospace and pharmaceutical. -

Roundtable Sustainability Series: the Packaging Industry

Executive Insights Roundtable Sustainability Series: The Packaging Industry We recently held an in-depth conversation about Recycled packaging can involve different substrates, or materials, sustainability’s impact on packaging with three such as tin, recycled plastics, recycled paperboard and wood chips. Recycled packaging is the most prevalent sustainable leaders in L.E.K. Consulting’s Paper & Packaging packaging product. Over the years, the quality of recycled practice: Thilo Henkes, Managing Director and packaging products has improved so much that some recycled packaging can be used in contact with food. However, we have practice head; Jeff Cloetingh, Managing Director; yet to see a recycled or biodegradable packaging product that and Rory Murphy, Principal. Excerpts from our can be used in medical applications that require sterility. wide-ranging discussion can be found below. Reusable packaging has been coming into vogue over the past few years. It involves a reusable container — for example, a How do you define sustainability in packaging? metal container that you can bring back to the store and get Thilo Henkes: Sustainability is a pressing topic in packaging; it’s a refilled. You see it mostly with food — Nestle is using it for ice growing segment of the packaging sector that is experiencing a lot cream — and some personal care applications such as shampoos of innovation as consumers increasingly focus on how sustainable and body creams. the packaging is for the products they purchase. Brands and what they stand for are embodied in their packaging, and a lot What is defined as sustainable packaging? of packaging gets discarded, so brands are increasingly giving In the market today there are three types of substrates the sustainability of their packaging attention as some consumer that fall under the definition of sustainable: biodegradable segments are making brand selection decisions based on it. -

Food Packaging Technology

FOOD PACKAGING TECHNOLOGY Edited by RICHARD COLES Consultant in Food Packaging, London DEREK MCDOWELL Head of Supply and Packaging Division Loughry College, Northern Ireland and MARK J. KIRWAN Consultant in Packaging Technology London Blackwell Publishing © 2003 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered Editorial Offices: trademarks, and are used only for identification 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ and explanation, without intent to infringe. Tel: +44 (0) 1865 776868 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK First published 2003 Tel: +44 (0) 1865 791100 Blackwell Munksgaard, 1 Rosenørns Allè, Library of Congress Cataloging in P.O. Box 227, DK-1502 Copenhagen V, Publication Data Denmark A catalog record for this title is available Tel: +45 77 33 33 33 from the Library of Congress Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd, 550 Swanston Street, Carlton South, British Library Cataloguing in Victoria 3053, Australia Publication Data Tel: +61 (0)3 9347 0300 A catalogue record for this title is available Blackwell Publishing, 10 rue Casimir from the British Library Delavigne, 75006 Paris, France ISBN 1–84127–221–3 Tel: +33 1 53 10 33 10 Originated as Sheffield Academic Press Published in the USA and Canada (only) by Set in 10.5/12pt Times CRC Press LLC by Integra Software Services Pvt Ltd, 2000 Corporate Blvd., N.W. Pondicherry, India Boca Raton, FL 33431, USA Printed and bound in Great Britain, Orders from the USA and Canada (only) to using acid-free paper by CRC Press LLC MPG Books Ltd, Bodmin, Cornwall USA and Canada only: For further information on ISBN 0–8493–9788–X Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: The right of the Author to be identified as the www.blackwellpublishing.com Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Bringing Reusable Packaging Systems to Life Lessons Learned from Testing Reusable Cups Table of Contents

Bringing Reusable Packaging Systems to Life Lessons Learned from Testing Reusable Cups Table of Contents Introduction SECTION 1 SECTION 4 Setting the Scene Experimentation in Action — Lessons Learned — Reuse Model Insights Piloting Innovative Reusable Top Insights for Reuse How It Works Cup Systems Models SECTION 2 SECTION 5 The Journey of a Reusable What’s Next? — Building the Cup — A Multi-Stage Journey Future for Reuse Models Customer Awareness Sign-up Point-of-Sale SECTION 6 Drink Preparation Point-of-Handoff Appendix Point-of-Return Terms to Know Washing & Sanitizing Citations Pick-up & Delivery Acknowledgements B L E Inventory A T O F SECTION 3 Bringing Reusable Packaging C Systems to Life – Critical O Inputs & Considerations for N Scale S T T Engage Diverse Stakeholders E N Make Sustainable Material Choices Select the Perfect Spot Choose the Right Payment Model Optimize Health & Safety Protocols Measure Impact and Success Bringing Reusable Packaging Systems to Life 2 Dear Reader, If you visualize the current journey of most products and packaging in our economy, including the single-use cup, it looks like a straight line that starts with extracting finite raw materials and ends at the landfill. fter decades of relying on this food, are accelerating the growth of reuse The key to success for reuse models is seemingly convenient linear models. Over the last few years, we’ve seen continually testing, honing and refining them. Asystem, its long hidden costs in innovative companies explore and harness And assessing the environmental impact of terms of economic and environmental groundbreaking reusable packaging and reusable packaging is paramount during this consequences have become clear, bringing refill models, such as Algramo piloting phase of experimentation — we must ensure we us to a tipping point that necessitates a their “smart dispensing” reuse model with don’t introduce new unintended consequences better way forward — one that considers companies like Nestlé and Unilever, among when replacing one system with another. -

Using Reusable Packaging to Optimize Your

60 Why Reusables? Using Plastic Reusable Packaging to Optimize Your Supply Chain Copyright ã2004 ORBIS Corporation Executive Overview Today’s supply chains are becoming more and more complex. With shorter product life cycles and rising customer demands, as well as the increasing spread of distribution, manufacturing, sourcing and engineering functions around the world, companies are seeking to successfully manage their supply chain, for improved profitability. 1 The good news: Those who have mastered supply chain excellence can experience up to 73% greater profit margins than other companies. 2 Plastic reusable packaging improves the flow of product all along the supply chain in many industries, to reduce total costs and achieve sustained optimization. Whether shipping plastic bottles to a soft drink bottler for filling; trim parts to an automotive manufacturer; electronic components to a computer manufacturer or consumer goods to the mass retailer, plastic reusable containers and pallets will help move product faster, better, safer and more cost effectively. Plastic reusable packaging is integrated in a single operation or entire supply chain to take the place of single-use corrugated shipping and storage boxes and limited-use wood pallets. Users experience a rapid return on their packaging investment…many times in 6-18 months or less. U.S. firms will spend on average $4.8 billion a year through 2008 to tune their supply network processes. 3 In this paper we will look closely at a basic supply chain model and address how companies, regardless -

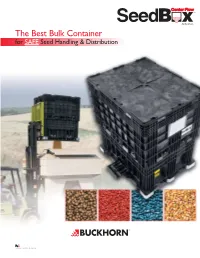

The Best Bulk Container

The Best Bulk Container for SAFE Seed Handling & Distribution ™ Content Security SeedBox Lids and discharge door can be sealed with security ties to Container prevent content contamination. ™ Tight Fitting Lid The reusable SeedBox Container Extra product protection against rain, rodents, from Buckhorn is the best, most dust, dirt, and other contaminants. Lids efficient, container available to feature reinforced ribbing, corner transport and dispense seeds. stacking supports, and water The Seedbox's unique design runoff channels. provides a safer work environment, saves labor by eliminating the need for flexible bulk bags, and reduces expendable packaging and disposal costs. The smooth, sloped interior and a generous, center discharge port empty contents safely, completely, and quickly – as fast as 30 seconds. Rugged Construction The container's high-strength, plastic Molded of high-density construction easily handles loads up polyethylene (HDPE) structural foam. Will not rust, peel, or to 2,500 lbs. (1,134kg), and multiple splinter. Resistant to water, containers interlock when stacked or mild acids and withstands nested for safe, stable storage. temperatures of –20° F to Nested containers take up 40% less 120° F (–28.8° C to 48.8° C). space, maximizing warehouse storage. SeedBox Containers are available exclusively from Buckhorn, your Cross-Member one source for reusable packaging Reinforcement opportunities that drive efficiency and Molded-in cross mem- bers for additional lateral costs savings in your supply chain. strength and reinforcement. Interior Funnel Design Smooth sides and funnel shape for complete emptying without tipping. Inspiring Innovation Buckhorn's Seedbox Container inspired equipment manufacturers to develop better transport vehicles that efficiently deliver seed to planters in the field. -

Download Catalog

DELIVERING VALUE BEYOND THE BOX BUCKHORN REUSABLE PACKAGING SOLUTIONS Reusable Packaging Solutions Product Catalog PRODUCT CATALOG Table of Contents Buckhorn Inc. Why Buckhorn .......................................................................................... 3-6 400 TechneCenter Drive, Suite 215 Bulk Boxes ..................................................................................................... 7 Milford, OH 45150 Bulk Boxes Overview ....................................................................................... 8-9 Toll Free: (800) 543-4454 General Purpose Boxes ................................................................................ 10-11 Tel: (513) 831-4402 Fax: (513) 831-5474 Standard-Duty Boxes ....................................................................................12-13 Extra-Duty Boxes ........................................................................................... 14-15 Heavy-Duty Boxes ......................................................................................... 16-17 Extended Length Boxes .............................................................................. 18-21 DunnageReady Boxes .................................................................................22-23 Agricultural Boxes ....................................................................................... 24-25 Bulk Box Accessories ........................................................................................26 Hand-Held Containers ...............................................................................27 -

Recycling Food Packaging & Food Waste in Plastics Revolution

Recycling food packaging & food waste in plastics revolution STUDY European Economic and Social Committee Recycling Food Packaging and Food Waste in Plastics Revolution Study The information and views set out in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee. The European Economic and Social Committee does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this study. Neither the European Economic and Social Committee nor any person acting on the European Economic and Social Committee’s behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. General information STUDY FOR The European Economic and Social Committee (EESC) REQUESTING SERVICE Legislative Planning, Relations with Institutions and Civil Society Directorate STUDY MANAGING SERVICE Foresight, Studies and Policy Assessment Unit DATE October 2020 (corrected version) MAIN CONTRACTOR ADS Insight AUTHORS Aida Axelsson-Bakri, Mikaela Nordenfelt, Tina Ajdič, Eric Le Nail CONTACTS [email protected] IDENTIFIERS ISBN doi STUDY print QE-03-20-534-EN-C 978-92-830-4882-4 10.2864/539724 PDF QE-03-20-534-EN-N 978-92-830-4881-7 10.2864/154293 0 Table of Contents Abstract 1 Executive Summary 2 1. Introduction 7 1.1 Objectives and scope of the study 7 1.2 Methodology 8 1.3 Definition of Sustainable Food Packaging 8 2. Policy and Other Trends and Drivers 10 2.1 EU Policy: context, legislation, and binding targets 10 2.2 Future EU political debate and priorities 12 2.3 Other Trends & Drivers 14 3. -

The New Plastics Economy Rethinking the Future of Plastics

THE NEW PLASTICS ECONOMY • • • 1 The New Plastics Economy Rethinking the future of plastics THE NEW PLASTICS ECONOMY RETHINKING THE FUTURE OF PLASTICS 2 • • • THE NEW PLASTICS ECONOMY THE NEW PLASTICS ECONOMY • • • 3 CONTENTS Preface 4 Foreword 5 In support of the New Plastics Economy 6 Project MainStream 8 Disclaimer 9 Acknowledgements 10 Global partners of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation 14 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 15 PART I SUMMARY OF FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS 22 1 The case for rethinking plastics, starting with packaging 24 2 The New Plastics Economy: Capturing the opportunity 31 3 The New Plastics Economy demands a new approach 39 PART II CREATING AN EFFECTIVE AFTER-USE PLASTICS ECONOMY 44 4 Recycling: Drastically increasing economics, uptake and quality through compounding and mutually reinforcing actions 46 5 Reuse: Unlocking material savings and beyond 62 6 Compostable packaging: Returning nutrients to the soil for targeted packaging applications 68 PART III DRASTICALLY REDUCING LEAKAGE OF PLASTICS INTO NATURAL SYSTEMS AND MINIMISING OTHER EXTERNALITIES 74 7 Drastically reducing leakage into natural systems and associated negative impacts 76 8 Substances of concern: Capturing value with materials that are safe in all product phases 79 PART IV DECOUPLING PLASTICS FROM FOSSIL FEEDSTOCKS 86 9 Dematerialisation: Doing more with less plastic 88 10 Renewably sourced plastics: Decoupling plastics production from fossil feedstocks 92 Appendix 97 Appendix A. Global material flow analysis: definitions and sources 98 Appendix B. Biodegradation 100 Appendix C. Anaerobic digestion 101 Glossary 102 List of Figures and Boxes 105 Endnotes 106 About the Ellen MacArthur Foundation 117 4 • • • THE NEW PLASTICS ECONOMY PREFACE The circular economy is gaining growing attention as a potential way for our society to increase prosperity, while reducing demands on finite raw materials and minimising negative externalities. -

Coca-Cola 2020 World Without Waste Report

2020 World Without Waste Report THE COMPANY Introduction Design Collect Partner What’s Next Assurance Statement Design Make 100% of our packaging recyclable globally by 2025—and We have a responsibility to help solve the global use at least 50% recycled material plastic waste crisis. That’s why, in 2018, we in our packaging by 2030. launched World Without Waste—an ambitious, sustainable packaging initiative that is creating systemic change by driving a circular economy Collect for our bottles and cans. Collect and recycle a bottle or can for each one we sell by 2030. The World Without Waste strategy has signaled a renewed focus on our entire packaging lifecycle—from how bottles and cans are Partner designed and produced to how they’re recycled Bring people together to and repurposed—through a focus on three support a healthy, debris-free environment. fundamental goals: Our sustainability priorities are interconnected, so we approach them holistically. Because packaging accounts for approximately 30% of our overall carbon footprint, our World Without Waste strategy is essential to meeting our Science-Based Target for climate. We lower our carbon footprint by using more recycled material; by lightweighting our packaging; by focusing on refillable, dispensed and Coca-Cola Freestyle solutions; by developing alternative packaging materials, such as advanced, plant-based packaging that requires less fossil fuel; and by investing in local recycling programs to collect plastic and glass bottles and cans so they can become new ones. This is our third World Without Waste progress report (read our 2018 and 2019 reports). Three years into this transformational journey, the global conversation about plastic pollution—and calls for urgent, collaborative action—are intensifying. -

Reusable Vs Single-Use Packaging

REUSABLE VS A review of SINGLE-USE environmental PACKAGING impacts EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 A REVIEW OF ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS As the global population has grown and Currently, most waste management society has become more fast-paced, there systems prioritise recycling as the has been an increased demand for, and main method of reducing the amount therefore production of, more convenient, of waste going to disposal, which, in easy-to-use, on-the-go products. This terms of circular economy strategies, demand, coupled with globalisation and should be considered as one of the last trade liberalisation, has translated into management options, after it has been consumption patterns that are taking a toll determined that the product (or parts of on Earth’s capacity to replenish itself. In it) can no longer be reused, repurposed, Europe, packaging alone represents 36% remanufactured or reinserted into the of municipal solid waste1. While individual production line. On top of that, materials countries attempt to solve their waste are not being recycled at a high enough management issues and resources continue rate to ensure that our waste is managed to be depleted at a rate faster than they can sustainably. Reuse avoids the need for be regenerated, the global economy loses resource extraction and reduces energy about $80-120 billion in packaging that use compared to the manufacturing of could be reused or recycled2. new products and recycling. In addition, it can incentivise a shift toward more conscious consumption and reshape our relationship to products. This report aims at understanding the benefits of reuse by evaluating the multi-layered environmental impacts of both single-use and reusable types of packaging through an in-depth comparative analysis of 32 Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) studies.