Democratizing the World Trade Organization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Global Trading System

COVER STORY • Global Governance at a Crossroads – a Roadmap Towards the G20 Summit in Osaka • 3 he Global Trading System: What Went Wrong & How to Fix It TBy Edward Alden Author Edward Alden Introduction in what will become a prolonged era of growing nationalism and protectionism. Gideon Rachman, the Financial Times columnist, has It has now been more than a quarter century since the United argued that the nationalist backlash symbolized by Trump’s election States, the European Union (EU), Japan and more than 100 other and the 2016 Brexit vote in the United Kingdom is likely to spread to countries came together to conclude the Uruguay Round global trade other countries and persist for several decades. But, he noted, those agreement and establish the World Trade Organization (WHO). It was movements will have to show that they can deliver not just promises a time of extraordinary optimism. Mickey Kantor, US trade but real economic results. So far – as the process of the UK representative for President Bill Clinton, had endured many sleepless government and parliament’s efforts to leave the EU show – real nights with his counterparts to bring the deal home by the Dec. 15, economic results have not been delivered. But champions of 1993 deadline. He promised the new agreement would “raise the globalization and the “rules-based trading system” cannot simply standard of living not only for Americans, but for workers all over the wait and hope that the failures of economic nationalism will become world”. Every American family, he said, would gain some $17,000 evident. -

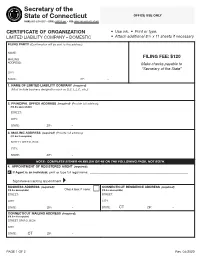

Certificate of Organization (LLC

Secretary of the State of Connecticut OFFICE USE ONLY PHONE: 860-509-6003 • EMAIL: [email protected] • WEB: www.concord-sots.ct.gov CERTIFICATE OF ORGANIZATION • Use ink. • Print or type. LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY – DOMESTIC • Attach additional 8 ½ x 11 sheets if necessary. FILING PARTY (Confirmation will be sent to this address): NAME: FILING FEE: $120 MAILING ADDRESS: Make checks payable to “Secretary of the State” CITY: STATE: ZIP: – 1. NAME OF LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY (required) (Must include business designation such as LLC, L.L.C., etc.): 2. PRINCIPAL OFFICE ADDRESS (required) (Provide full address): (P.O. Box unacceptable) STREET: CITY: STATE: ZIP: – 3. MAILING ADDRESS (required) (Provide full address): (P.O. Box IS acceptable) STREET OR P.O. BOX: CITY: STATE: ZIP: – NOTE: COMPLETE EITHER 4A BELOW OR 4B ON THE FOLLOWING PAGE, NOT BOTH. 4. APPOINTMENT OF REGISTERED AGENT (required): A. If Agent is an individual, print or type full legal name: _______________________________________________________________ Signature accepting appointment ▸ ____________________________________________________________________________________ BUSINESS ADDRESS (required): CONNECTICUT RESIDENCE ADDRESS (required): (P.O. Box unacceptable) Check box if none: (P.O. Box unacceptable) STREET: STREET: CITY: CITY: STATE: ZIP: – STATE: CT ZIP: – CONNECTICUT MAILING ADDRESS (required): (P.O. Box IS acceptable) STREET OR P.O. BOX: CITY: STATE: CT ZIP: – PAGE 1 OF 2 Rev. 04/2020 Secretary of the State of Connecticut OFFICE USE ONLY PHONE: 860-509-6003 • EMAIL: [email protected] -

A Citizen's Guide to the World Trade Organization

A Citizens Guide to THE WORLD TRADE A Citizens Guide to the World Trade ORGANIZATION Organization Published by the Working Group on the WTO / MAI, July 1999 Printed in the U.S. by Inkworks, a worker- owned union shop ISBN 1-58231-000-9 EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW TO The contents of this pamphlet may be freely reproduced provided that its source FIGHT FOR is acknowledged. FAIR TRADE THE WTO AND this system sidelines environmental rules, health safeguards and labor CORPORATE standards to provide transnational GLOBALIZATION corporations (TNCs) with a cheap supply of labor and natural resources. The WTO also guarantees corporate access to What do the U.S. Cattlemen’s Associa- foreign markets without requiring that tion, Chiquita Banana and the Venezu- TNCs respect countries’ domestic elan oil industry have in common? These priorities. big business interests were able to defeat hard-won national laws ensuring The myth that every nation can grow by food safety, strengthening local econo- exporting more than they import is central mies and protecting the environment by to the neoliberal ideology. Its proponents convincing governments to challenge the seem to forget that in order for one laws at the World Trade Organization country to export an automobile, some (WTO). other country has to import it. Established in 1995, the WTO is a The WTO Hurts U.S. Workers - Steel powerful new global commerce agency, More than 10,000 which transformed the General Agree- high-wage, high-tech ment on Tarriffs and Trade (GATT) into workers in the U.S. an enforceable global commercial code. -

Organizational Culture Model

A MODEL of ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE By Don Arendt – Dec. 2008 In discussions on the subjects of system safety and safety management, we hear a lot about “safety culture,” but less is said about how these concepts relate to things we can observe, test, and manage. The model in the diagram below can be used to illustrate components of the system, psychological elements of the people in the system and their individual and collective behaviors in terms of system performance. This model is based on work started by Stanford psychologist Albert Bandura in the 1970’s. It’s also featured in E. Scott Geller’s text, The Psychology of Safety Handbook. Bandura called the interaction between these elements “reciprocal determinism.” We don’t need to know that but it basically means that the elements in the system can cause each other. One element can affect the others or be affected by the others. System and Environment The first element we should consider is the system/environment element. This is where the processes of the SMS “live.” This is also the most tangible of the elements and the one that can be most directly affected by management actions. The organization’s policy, organizational structure, accountability frameworks, procedures, controls, facilities, equipment, and software that make up the workplace conditions under which employees work all reside in this element. Elements of the operational environment such as markets, industry standards, legal and regulatory frameworks, and business relations such as contracts and alliances also affect the make up part of the system’s environment. These elements together form the vital underpinnings of this thing we call “culture.” Psychology The next element, the psychological element, concerns how the people in the organization think and feel about various aspects of organizational performance, including safety. -

World Trade Statistical Review 2021

World Trade Statistical Review 2021 8% 4.3 111.7 4% 3% 0.0 -0.2 -0.7 Insurance and pension services Financial services Computer services -3.3 -5.4 World Trade StatisticalWorld Review 2021 -15.5 93.7 cultural and Personal, services recreational -14% Construction -18% 2021Q1 2019Q4 2019Q3 2020Q1 2020Q4 2020Q3 2020Q2 Merchandise trade volume About the WTO The World Trade Organization deals with the global rules of trade between nations. Its main function is to ensure that trade flows as smoothly, predictably and freely as possible. About this publication World Trade Statistical Review provides a detailed analysis of the latest developments in world trade. It is the WTO’s flagship statistical publication and is produced on an annual basis. For more information All data used in this report, as well as additional charts and tables not included, can be downloaded from the WTO web site at www.wto.org/statistics World Trade Statistical Review 2021 I. Introduction 4 Acknowledgements 6 A message from Director-General 7 II. Highlights of world trade in 2020 and the impact of COVID-19 8 World trade overview 10 Merchandise trade 12 Commercial services 15 Leading traders 18 Least-developed countries 19 III. World trade and economic growth, 2020-21 20 Trade and GDP in 2020 and early 2021 22 Merchandise trade volume 23 Commodity prices 26 Exchange rates 27 Merchandise and services trade values 28 Leading indicators of trade 31 Economic recovery from COVID-19 34 IV. Composition, definitions & methodology 40 Composition of geographical and economic groupings 42 Definitions and methodology 42 Specific notes for selected economies 49 Statistical sources 50 Abbreviations and symbols 51 V. -

Trade and Employment Challenges for Policy Research

ILO - WTO - ILO TRADE AND EMPLOYMENT CHALLENGES FOR POLICY RESEARCH This study is the outcome of collaborative research between the Secretariat of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the TRADE AND EMPLOYMENT International Labour Office (ILO). It addresses an issue that is of concern to both organizations: the relationship between trade and employment. On the basis of an overview of the existing academic CHALLENGES FOR POLICY RESEARCH literature, the study provides an impartial view of what can be said, and with what degree of confidence, on the relationship between trade and employment, an often contentious issue of public debate. Its focus is on the connections between trade policies, and labour and social policies and it will be useful for all those who are interested in this debate: academics and policy-makers, workers and employers, trade and labour specialists. WTO ISBN 978-92-870-3380-2 A joint study of the International Labour Office ILO ISBN 978-92-2-119551-1 and the Secretariat of the World Trade Organization Printed by the WTO Secretariat - 813.07 TRADE AND EMPLOYMENT CHALLENGES FOR POLICY RESEARCH A joint study of the International Labour Office and the Secretariat of the World Trade Organization Prepared by Marion Jansen Eddy Lee Economic Research and Statistics Division International Institute for Labour Studies World Trade Organization International Labour Office TRADE AND EMPLOYMENT: CHALLENGES FOR POLICY RESEARCH Copyright © 2007 International Labour Organization and World Trade Organization. Publications of the International Labour Office and World Trade Organization enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. -

the Wto, Imf and World Bank

ISSN: 1726-9466 13 F ULFILLING THE MARRAKESH MANDATE ON COHERENCE: ISBN: 978-92-870-3443-4 TEN YEARS OF COOPERATION BETWEEN THE WTO, IMF AND WORLD BANK by MARC AUBOIN Printed by the WTO Secretariat - 6006.07 DISCUSSION PAPER NO 13 Fulfi lling the Marrakesh Mandate on Coherence: Ten Years of Cooperation between the WTO, IMF and World Bank by Marc Auboin Counsellor, Trade and Finance and Trade Facilitation Division World Trade Organization Geneva, Switzerland Disclaimer and citation guideline Discussion Papers are presented by the authors in their personal capacity and opinions expressed in these papers should be attributed to the authors. They are not meant to represent the positions or opinions of the WTO Secretariat or of its Members and are without prejudice to Members’ rights and obligations under the WTO. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors. Any citation of this paper should ascribe authorship to staff of the WTO Secretariat and not to the WTO. This paper is only available in English – Price CHF 20.- To order, please contact: WTO Publications Centre William Rappard 154 rue de Lausanne CH-1211 Geneva Switzerland Tel: (41 22) 739 52 08 Fax: (41 22) 739 57 92 Website: www.wto.org E-mail: [email protected] ISSN 1726-9466 ISBN: 978-92-870-3443-4 Printed by the WTO Secretariat IX-2007 Keywords: coherence, cooperation in global economic policy making, economic policy coordination, cooperation between international organizations. © World Trade Organization, 2007. Reproduction of material contained in this document may be made only with written permission of the WTO Publications Manager. -

Customer Relationship Management and Leadership Sponsorship

Abilene Christian University Digital Commons @ ACU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-2019 Customer Relationship Management and Leadership Sponsorship Jacob Martin [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Martin, Jacob, "Customer Relationship Management and Leadership Sponsorship" (2019). Digital Commons @ ACU, Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 124. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ACU. This dissertation, directed and approved by the candidate’s committee, has been accepted by the College of Graduate and Professional Studies of Abilene Christian University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Education in Organizational Leadership Dr. Joey Cope, Dean of the College of Graduate and Professional Studies Date Dissertation Committee: Dr. First Name Last Name, Chair Dr. First Name Last Name Dr. First Name Last Name Abilene Christian University School of Educational Leadership Customer Relationship Management and Leadership Sponsorship A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Organizational Leadership by Jacob Martin December 2018 i Acknowledgments I would not have been able to complete this journey without the support of my family. My wife, Christal, has especially been supportive, and I greatly appreciate her patience with the many hours this has taken over the last few years. I also owe gratitude for the extra push and timely encouragement from my parents, Joe Don and Janet, and my granddad Dee. -

English Business Organization Law During the Industrial Revolution

Choosing the Partnership: English Business Organization Law During the Industrial Revolution Ryan Bubb* I. INTRODUCTION For most of the period associated with the Industrial Revolution in Britain, English law restricted access to incorporation and the Bubble Act explicitly outlawed the formation of unincorporated joint stock com- panies with transferable shares. Furthermore, firms in the manufacturing industries most closely associated with the Industrial Revolution were overwhelmingly partnerships. These two facts have led some scholars to posit that the antiquated business organization law was a constraint on the structural transformation and growth that characterized the British economy during the period. For example, Professor Ron Harris argues that the limitation on the joint stock form was “less than satisfactory in terms of overall social costs, efficient allocation of resources, and even- 1 tually the rate of growth of the English economy.” * Associate Professor of Law, New York University School of Law. Email: [email protected]. For helpful comments I am grateful to Ed Glaeser, Ron Harris, Eric Hilt, Giacomo Ponzetto, Max Schanzenbach, and participants in the Berle VI Symposium at Seattle University Law School, the NYU Legal History Colloquium, and the Harvard Economic History Tea. I thank Alex Seretakis for superb research assistance. 1. RON HARRIS, INDUSTRIALIZING ENGLISH LAW: ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND BUSINESS ORGANIZATION, 1720–1844, at 167 (2000). There are numerous other examples of this and related arguments in the literature. While acknowledging that, to a large extent, restrictions on the joint stock form could be overcome by alternative arrangements, Nick Crafts nonetheless argues that “institutional weaknesses relating to . company legislation . must have had some inhibiting effects both on savers and on business investment.” Nick Crafts, The Industrial Revolution, in 1 THE ECONOMIC HISTORY OF BRITAIN SINCE 1700, at 44, 52 (Roderick Floud & Donald N. -

A Guide to Nonprofit Board Service in Oregon

A GUIDE TO NONPROFIT BOARD SERVICE IN OREGON Office of the Attorney General A GUIDE TO NONPROFIT BOARD SERVICE Dear Board Member: Thank you for serving as a director of a nonprofit charitable corporation. Oregonians rely heavily on charitable corporations to provide many public benefits, and our quality of life is dependent upon the many volunteer directors who are willing to give of their time and talents. Although charitable corporations vary a great deal in size, structure and mission, there are a number of principles which apply to all such organizations. This guide is provided by the Attorney General’s office to assist board members in performing these important functions. It is only a guide and is not meant to suggest the exact manner that board members must act in all situations. Specific legal questions should be directed to your attorney. Nevertheless, we believe that this guide will help you understand the three “R”s associated with your board participation: your role, your rights, and your responsibilities. Active participation in charitable causes is critical to improving the quality of life for all Oregonians. On behalf of the public, I appreciate your dedicated service. Sincerely, Ellen F. Rosenblum Attorney General 1 UNDERSTANDING YOUR ROLE Board members are recruited for a variety of reasons. Some individuals are talented fundraisers and are sought by charities for that reason. Others bring credibility and prestige to an organization. But whatever the other reasons for service, the principal role of the board member is stewardship. The directors of the corporation are ultimately responsible for the management of the affairs of the charity. -

Collaboration

Partnership, Collaboration: depend on partnerships with local housing Why Form a Partnership? authorities and private development firms to What is the Difference? provide shelter and transitional housing units for With a strong partnership, your organization may their homeless clients. have access to more financial resources, tangible A legal partnership is a contractual relationship resources, people resources, licensed client involving close cooperation between two or more Collaborations are the most immediate, economical services, and professional expertise. Investors, parties having specified and joint rights and way to enhance the services an organization can such as foundations and government grants, will responsibilities. Each party has an equal share of offer homeless veterans. Gaining access to services be more likely to consider your program the risk as well as the reward. that are already provided by community-based proposals because more areas of need are organizations and agencies is critical in containing A collaboration involves cooperation in which addressed and there is less duplication of services. costs while maximizing program benefits. Support parties are not necessarily bound contractually. organizations, in turn, can justify funding requests There is a relationship, but it is usually less formal based on services they offer to homeless veterans. How do you find and select a than a binding, legal contract and responsibilities partner? may not be shared equally. A collaboration exists Where to Find Vital Services when several people pool their common interests, • Define what your clients needs are (both assets and professional skills to promote broader The following is a list of services most homeless current and future). -

Balance-Of-Payments Crises in the Developing World: Balancing Trade, Finance and Development in the New Economic Order Chantal Thomas

American University International Law Review Volume 15 | Issue 6 Article 3 2000 Balance-of-Payments Crises in the Developing World: Balancing Trade, Finance and Development in the New Economic Order Chantal Thomas Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Thomas, Chantal. "Balance-of-Payments Crises in the Developing World: Balancing Trade, Finance and Development in the New Economic Order." American University International Law Review 15, no. 6 (2000): 1249-1277. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BALANCE-OF-PAYMENTS CRISES IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD: BALANCING TRADE, FINANCE AND DEVELOPMENT IN THE NEW ECONOMIC ORDER CHANTAL THOMAS' INTRODUCTION ............................................ 1250 I. CAUSES OF BALANCE-OF-PAYMENTS CRISES ...... 1251 II. INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC LAW ON BALANCE- OF-PAYVIENTS CRISES ................................ 1255 A. THE TRADE SIDE: THE GATT/WTO ...................... 1255 1. The Basic Legal Rules .................................. 1255 2. The Operation of the Rules ........................... 1258 a. Substantive Dynamics ................................ 1259 b. Institutional Dynam ics ................................ 1260 B. THE MONETARY SIDE: THE IMF ......................... 1261 C. THE ERA OF DEEP INTEGRATION .......................... 1263 III. INDIA AND ITS BALANCE-OF-PAYMENTS TRADE RESTRICTION S .............................................. 1265 A. THE TRANSFORMATION OF INDIA .......................... 1265 B. THE WTO BALANCE-OF-PAYMENTS CASE ................ 1269 1. The Substantive Arguments ............................ 1270 a.