How to Analyze Non-Profit Financial Statements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

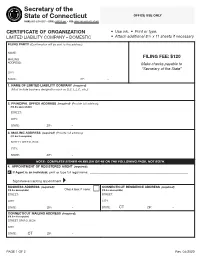

Certificate of Organization (LLC

Secretary of the State of Connecticut OFFICE USE ONLY PHONE: 860-509-6003 • EMAIL: [email protected] • WEB: www.concord-sots.ct.gov CERTIFICATE OF ORGANIZATION • Use ink. • Print or type. LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY – DOMESTIC • Attach additional 8 ½ x 11 sheets if necessary. FILING PARTY (Confirmation will be sent to this address): NAME: FILING FEE: $120 MAILING ADDRESS: Make checks payable to “Secretary of the State” CITY: STATE: ZIP: – 1. NAME OF LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY (required) (Must include business designation such as LLC, L.L.C., etc.): 2. PRINCIPAL OFFICE ADDRESS (required) (Provide full address): (P.O. Box unacceptable) STREET: CITY: STATE: ZIP: – 3. MAILING ADDRESS (required) (Provide full address): (P.O. Box IS acceptable) STREET OR P.O. BOX: CITY: STATE: ZIP: – NOTE: COMPLETE EITHER 4A BELOW OR 4B ON THE FOLLOWING PAGE, NOT BOTH. 4. APPOINTMENT OF REGISTERED AGENT (required): A. If Agent is an individual, print or type full legal name: _______________________________________________________________ Signature accepting appointment ▸ ____________________________________________________________________________________ BUSINESS ADDRESS (required): CONNECTICUT RESIDENCE ADDRESS (required): (P.O. Box unacceptable) Check box if none: (P.O. Box unacceptable) STREET: STREET: CITY: CITY: STATE: ZIP: – STATE: CT ZIP: – CONNECTICUT MAILING ADDRESS (required): (P.O. Box IS acceptable) STREET OR P.O. BOX: CITY: STATE: CT ZIP: – PAGE 1 OF 2 Rev. 04/2020 Secretary of the State of Connecticut OFFICE USE ONLY PHONE: 860-509-6003 • EMAIL: [email protected] -

Assurance on XBRL Instance Document: a Conceptual Framework of Assertions

Assurance on XBRL Instance Document: A Conceptual Framework of Assertions Rajendra P. Srivastava Ernst & Young Professor and Director Ernst & Young Center for Auditing Research and Advanced Technology School of Business, The University of Kansas 1300 Sunnyside Avenue, Lawrence, Kansas 66045 Email: [email protected] and Alexander Kogan Department of Accounting and Information Systems Rutgers Business School – Newark and New Brunswick Rutgers University 180 University Avenue, Newark, NJ 07102-1895 Email: [email protected] 1 Assurance on XBRL Instance Document: A Conceptual Framework of Assertions ABSTRACT XBRL stands for extensible business reporting language. It is an XML based computer language for reporting business information. Starting December 2008, the United States Security and Exchange Commission (US SEC) has a proposal requiring top 500 public companies to file their financial statements with the SEC not only in the text format (i.e., in ASCII or HTML) but also in the XBRL format. The file created using XRBL language is called an XBRL instance document. Under this requirement, the filers are not required to obtain a third party assurance on the XBRL instance document. The main reason for not requiring a third party independent assurance of XBRL instance documents is to encourage filers to comply with the SEC requirement without incurring much added costs. In addition, to encourage the filers to comply with this requirement, the SEC is not holding filers legally liable of any errors in the filed XBRL instance documents so long as they look similar to the standard reports when viewed using the SEC viewer. Even though the SEC is not currently requiring a third party assurance of the XBRL instance documents of the SEC filings, it is in the best interest of the public that these documents be assured. -

Financial Forecasts and Projections 1473

Financial Forecasts and Projections 1473 AT Section 301 Financial Forecasts and Projections Source: SSAE No. 10; SSAE No. 11; SSAE No. 17. Effective when the date of the practitioner’s report is on or after June 1, 2001, unless otherwise indicated. Introduction .01 This section sets forth standards and provides guidance to practition- ers who are engaged to issue or do issue examination (paragraphs .29–.50), compilation (paragraphs .12–.28), or agreed-upon procedures reports (para- graphs .51–.56) on prospective financial statements. .02 Whenever a practitioner (a) submits, to his or her client or others, prospective financial statements that he or she has assembled, or assisted inas- sembling, that are or reasonably might be expected to be used by another (third) party1 or (b) reports on prospective financial statements that are, or reasonably might be expected to be used by another (third) party, the practitioner should perform one of the engagements described in the preceding paragraph. In de- ciding whether the prospective financial statements are or reasonably might be expected to be used by a third party, the practitioner may rely on either the written or oral representation of the responsible party, unless information comes to his or her attention that contradicts the responsible party's represen- tation. If such third-party use of the prospective financial statements is not reasonably expected, the provisions of this section are not applicable unless the practitioner has been engaged to examine, compile, or apply agreed-upon procedures to the prospective financial statements. .03 This section also provides standards for a practitioner who is engaged to examine, compile, or apply agreed-upon procedures to partial presentations. -

Financial Statements

FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Dr. Derek Farnsworth | Assistant Professor Financial Statements Financial Statements Key Concepts • The two primary financial statements – Balance Sheet – Income Statement • Debt vs equity • Book vs market value • Income vs cash flow • Average vs marginal tax rate Key Terms Review • Asset – something you have • Liability – something you owe (debt) • Equity – net value of the business – Equity = Assets – Liabilities New Terms − Liquidity – Speed and ease of conversion to cash without significant loss of value − Valuable in avoiding financial distress • Current vs fixed or long term – An asset or liability is “current” if it converts to cash within a year The Balance Sheet • A snapshot of the firm’s assets and liabilities at a given point in time (“as of …”) • Assets − Left-hand side (or upper portion) − In order of decreasing liquidity • Liabilities and Owners’ Equity – Right-hand side (or lower portion) – In ascending order of when due to be paid • Balance Sheet Identity ▪ Assets = Liabilities + Owners’ Equity (ALOE) The Balance Sheet Total Value of Assets Total Value of Liabilities and Shareholders' Equity Net Working Current Liabilities Current Assets Capital Long Term Debt Fixed Assets 1. Tangible 2. Intangible Shareholder Equity The Balance Sheet Balance Sheet Examples • Let’s examine some balance sheets! • SCORE Balance Sheet • FSA Balance Sheet Accrued Interest? • Let’s get Investopedia to help! • http://www.investopedia.com/terms/a/accrue dinterest.asp Balance Sheet Activity • Balance Sheets have a particular -

OIG-18-031 Financial Management: Audit of the Bureau

Audit Report OIG-18-031 FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT Audit of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing’s Fiscal Years 2017 and 2016 Financial Statements December 19, 2017 Office of Inspector General Department of the Treasury This Page Intentionally Left Blank DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY WASHINGTON, D.C. 20220 OFFICE OF December 19, 2017 INSPECTOR GENERAL MEMORANDUM FOR LEONARD R. OLIJAR, DIRECTOR BUREAU OF ENGRAVING AND PRINTING FROM: James Hodge /s/ Director, Financial Audit SUBJECT: Audit of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing’s Fiscal Years 2017 and 2016 Financial Statements I am pleased to transmit the attached subject report. Under a contract monitored by our office, KPMG LLP (KPMG), an independent certified public accounting firm, audited the financial statements of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) as of September 30, 2017 and 2016, and for the years then ended, and provided an opinion on the financial statements, an opinion on management’s assertion that BEP maintained effective internal control over financial reporting, and a report on compliance with laws, regulations, and contracts tested. The contract required that the audit be performed in accordance with U.S. generally accepted government auditing standards, Office of Management and Budget Bulletin No. 17-03, Audit Requirements for Federal Financial Statements, and the Government Accountability Office/President’s Council on Integrity and Efficiency, Financial Audit Manual. In its audit of BEP, KPMG found • the financial statements were fairly presented, in all material respects, in accordance with U.S. generally accepted accounting principles; • management’s assertion that BEP maintained effective internal control over financial reporting as of September 30, 2017, was fairly stated in all material respects; and • no instances of reportable noncompliance with laws, regulations, and contracts tested. -

CFA Level 1 Financial Ratios Sheet

CFA Level 1 Financial Ratios Sheet Activity Ratios Solvency ratios Ratio calculation Activity ratios measure how efficiently a company performs Total debt Debt-to-assets day-to-day tasks, such as the collection of receivables and Total assets management of inventory. The table below clarifies how to Total debt Dept-to-capital calculate most of the activity ratios. Total debt + Total shareholders’ equity Total debt Dept-to-equity Total shareholders’ equity Activity Ratios Ratio calculation Average total assets Financial leverage Cost of goods sold Total shareholders’ equity Inventory turnover Average inventory Number of days in period Days of inventory on hands (DOH) Coverage Ratios Ratio calculation Inventory turnover EBIT Revenue or Revenue from credit sales Interest coverage Receivables turnover Interest payements Average receivables EBIT + Lease payements Number of days Fixed charge coverage Days of sales outstanding (DSO) Interest payements + Lease payements Receivable turnover Purchases Payable Turnover Average payables Profitability Ratios Number of days in a period Number of days of payables Payable turnover Profitability ratios measure the company’s ability to Revenue generate profits from its resources (assets). The table below Working capital turnover Average working capital shows the calculations of these ratios. Revenue Fixed assets turnover Average fixed assets Return on sales ratios Ratio calculation Revenue Total assets turnover Average total assets Gross profit Gross profit margin Revenue Operating profit Operating margin Liquidity Ratios Revenue EBT (Earnings Before Taxes) Pretax margin Liquidity ratios measure the company’s ability to meet its Revenue short-term obligations and how quickly assets are converted Net income Net profit margin into cash. The following table explains how to calculate the Revenue major liquidity ratios. -

An Introduction to Basic Farm Financial Statements: Balance Sheet

W 884 An Introduction to Basic Farm Financial Statements: Balance Sheet Victoria Campbell, Extension Intern S. Aaron Smith, Associate Professor Christopher N. Boyer, Associate Professor Andrew P. Griffith, Associate Professor Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics The image part with relationship ID rId2 was not found in the file. Introduction Basic Accounting Overview To begin constructing a balance sheet, we Tennessee agriculture includes a diverse list need to first start with the standard of livestock, poultry, fruits and vegetables, accounting equation: row crop, nursery, forestry, ornamental, agri- Total Assets = Total Liabilities + Owner’s tourism, value added and other Equity nontraditional enterprises. These farms vary in size from less than a quarter of an acre to The balance sheet is designed with assets on thousands of acres, and the specific goal for the left-hand side and liabilities plus owner’s each farm can vary. For example, producers’ equity on the right-hand side. This format goals might include maximizing profits, allows both sides of the balance sheet to maintaining a way of life, enjoyment, equal each other. After all, a balance sheet transitioning the operation to the next must balance. generation, etc. Regardless of the farm size, enterprises and objectives, it is important to keep proper farm financial records to improve the long- term viability of the farm. Accurate recordkeeping and organized financial statements allow producers to measure key financial components of their business such A change in liquidity, solvency and equity can as profitability, liquidity and solvency. These be found by comparing balance sheets from measurements are vital to making two different time periods. -

Preparing a Short-Term Cash Flow Forecast

Preparing a short-term What is a short-term cash How does a short-term cash flow forecast and why is it flow forecast differ from a cash flow forecast important? budget or business plan? 27 April 2020 The COVID-19 crisis has brought the importance of cash flow A short-term cash flow forecast is a forecast of the The income statement or profit and loss account forecasting and management into sharp focus for businesses. cash you have, the cash you expect to receive and in a budget or business plan includes non-cash the cash you expect to pay out of your business over accounting items such as depreciation and accruals This document explores the importance of forecasting, explains a certain period, typically 13 weeks. Fundamentally, for various expenses. The forecast cash flow how it differs from a budget or business plan and offers it’s about having good enough information to give statement contained in these plans is derived from practical tips for preparing a short-term cash flow forecast. you time and money to make the right business the forecast income statement and balance sheet decisions. on an indirect basis and shows the broad categories You can also access this information in podcast form here. of where cash is generated and where cash is spent. Forecasts are important because: They are produced on a monthly or quarterly basis. • They provide visibility of your future cash position In contrast, a short-term cash flow forecast: and highlight if and when your cash position is going to be tight. -

Illustrative IFRS Financial Statements 2019 – Investment Funds

Illustrative IFRS financial statements 2019 Investment funds Stay informed. Visit inform.pw c.com Illustrative IFRS financial statements 2019 – Investment funds Illustrative IFRS financial statements 2019 – Investment funds This publication provides an illustrative set of financial statements, prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), for a fictional open-ended investment fund (‘ABC Fund’ or the ‘Fund’). ABC Fund is an existing preparer of IFRS financial statements; IFRS 1, ‘First-time adoption of IFRS’, is not applicable. It does not have any subsidiaries, associates or joint ventures. The Fund’s shares are not traded in a public market. Guidance on financial statements for first-time adopters of IFRS is available at www.pwc.com/ifrs. This publication is based on the requirements of IFRS standards and interpretations for the financial year beginning on 1 January 2019. There are no standards effective for the first time in 2019 that required changes to the disclosures or accounting policies in this publication. However, readers should consider whether any of the standards that are mandatory for the first time for financial years beginning 1 January 2019 could affect their own accounting policies. Appendix XII contains a full list of these standards (including those that have only a disclosure impact) as well as a summary of their key requirements. In compiling the illustrative disclosures, we have updated the guidance included in Appendix VIII to address IFRIC 23 ‘Uncertainty over income tax treatments’ which is applicable for financial years beginning on or after 1 January 2019. Commentary boxes are included throughout the publication to provide additional information where necessary. -

Organizational Culture Model

A MODEL of ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE By Don Arendt – Dec. 2008 In discussions on the subjects of system safety and safety management, we hear a lot about “safety culture,” but less is said about how these concepts relate to things we can observe, test, and manage. The model in the diagram below can be used to illustrate components of the system, psychological elements of the people in the system and their individual and collective behaviors in terms of system performance. This model is based on work started by Stanford psychologist Albert Bandura in the 1970’s. It’s also featured in E. Scott Geller’s text, The Psychology of Safety Handbook. Bandura called the interaction between these elements “reciprocal determinism.” We don’t need to know that but it basically means that the elements in the system can cause each other. One element can affect the others or be affected by the others. System and Environment The first element we should consider is the system/environment element. This is where the processes of the SMS “live.” This is also the most tangible of the elements and the one that can be most directly affected by management actions. The organization’s policy, organizational structure, accountability frameworks, procedures, controls, facilities, equipment, and software that make up the workplace conditions under which employees work all reside in this element. Elements of the operational environment such as markets, industry standards, legal and regulatory frameworks, and business relations such as contracts and alliances also affect the make up part of the system’s environment. These elements together form the vital underpinnings of this thing we call “culture.” Psychology The next element, the psychological element, concerns how the people in the organization think and feel about various aspects of organizational performance, including safety. -

FS Double Dividend and Revenue Neutrality 01 02

Low Carbon Green Growth Roadmap for Asia and the Pacific FACT SHEET Figure 1: The double dividend through environmental tax and fiscal reforms Double dividend and revenue neutrality Key point • Double dividend and revenue neutrality principles enhance effectiveness, public acceptance and feasibility of environmental tax and fiscal reform measures. Double dividend and revenue neutrality explained The double dividend hypothesis states that a revenue neutral restructuring of the tax system, whereby green taxes are increased in proportion to a decrease in traditional taxes (income tax), could not only improve envi- ronmental quality (the first dividend) but also reduce the distortion of the tax system and the cost of labour, The prospects for winning the double dividend varies from country to country and depends on the structure of subsequently generating higher levels of employment (second dividend). relative preferences (the demand elasticity for ‘dirty’ goods and resources) and infrastructure available, the levels of investment in environmental research and development and the low use of distorting non- Revenue neutrality is a fiscal policy tool that can be used to overcome political resistance to an increase in envi- environmental taxes. ronmental taxes by seeking to have the same proportional reduction in income tax, pension contributions or possibly even value-added taxes (VAT), while striving to maintain a net-zero increase in the overall taxation of the It is also important to carefully design a supporting policy system, including regulations and investment environ- economy. ment, that will create incentives for a change of consumers towards environment-friendly consumption and to provide alternatives to more resource-inefficient lifestyles. -

Chapter 5 Consolidation Following Acquisition Consolidation Following

Consolidation Following Acquisition Chapter 5 • The procedures used to prepare a consolidated balance sheet as of the date of acquisition were introduced in the preceding chapter, that is, Consolidation Chapter 4. Following Acquisition • More than a consolidated balance sheet, however, is needed to provide a comprehensive picture of the consolidated entity’s activities following acquisition. McGraw-Hill/Irwin Copyright © 2005 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. 5-2 Consolidation Following Acquisition Consolidation Following Acquisition • The purpose of this chapter is to present the procedures used in the preparation of a • As with a single company, the set of basic consolidated balance sheet, income statement, financial statements for a consolidated entity and retained earnings statement subsequent consists of a balance sheet, an income to the date of combination. statement, a statement of changes in retained earnings, and a statement of cash flows. • The preparation of a consolidated statement of cash flows is discussed in Chapter 10. 5-3 5-4 Consolidation Following Acquisition Consolidation Following Acquisition • This chapter first deals with the important concepts of consolidated net income and consolidated retained earnings. • Finally, the remainder of the chapter deals with the specific procedures used to • Thereafter, the chapter presents a description prepare consolidated financial statements of the workpaper format used to facilitate the subsequent to the date of combination. preparation of a full set of consolidated financial statements. 5-5 5-6 1 Consolidation Following Acquisition Consolidation Following Acquisition • The discussion in the chapter focuses on procedures for consolidation when the parent company accounts for its investment in • Regardless of the method used by the parent subsidiary stock using the equity method.