Religion and Castes (Hindus)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JULY AUG SEPT OCT NOV DEC

Bank Holidays for 2017 State JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JULY AUG SEPT OCT NOV DEC Andhra Pradesh 14,26 12,29 1,5,14 1 26 15,25 2,28,30 1,2,19 4 1,25 Assam 14,26 12 14,15 1 26 15 2,29,30 2,18,19 4 25 1,2,19,26, Bihar 26 13,14,22 5,14 1 26 14,15 2,29,30 25 27 Chandigarh 5,26 10,24 13 1,4,13,14 26 15 2,15,19 4 25 Chattisgarh 26 24 13 1,9 10 26 15 2,30 1,2,19 4 2,25 Delhi 26 13 1,9,14 10 26 15 2,30 1,2,19 4 2,25 Goa 26 13,28 1,14 1 26^ 15,25,26 2^,30 2,18 4,19,25 Gujarat 14,26 24 13 1,4,9,14 26 7,15,25 2,30 1,2,19,20 2,25 Haryana 26 10,24 13 1,9,14 10 26 15 30 2,5,19 4 25 2,8*,19, Himachal Pradesh 5,26 10,24 13 1,4,15 10 26 7*,15 2,30 4 21* 22^,23^, 1^,5,8^, Jammu & Kashmir 26 24 12+,28 1,13,14 10 5,13 15 2^,3^,30 1^,2,19 4 26^ 25 2,28,29, Jharkand 26 24 12,13,30 1,4,9,14 10 26 15 1,2,19,26 4 2,25 30 2,19,29, 1,2,5,17#, Karnataka 14,26 24 29 1,9,14,29 1 26 15,25 1,6 1,4#,25 30 18,20 1^,3,4,6, Kerala 26 24 1,14,16 1 25^ 15 2,18 2^,25 21,29,30 Madya Pradesh 26 13 1,5,9,14 10 26 7,15 2,30 1,2,19 4 2,25 Maharashtra 26 19,24 13,28 1,4,9,14 1,10 26 15,17,25 2,30 1,2,19,20 4 1,25 Mahe 26 1,13,14 26^ 15,16 1^,3,4,29 2,15,18 1 1^,25 12,18,24, Meghalaya 1,26 13 14 16,17 15 2,29,30 2,19,20 10,23 25,26,30 Mizoram 2,11,26 20 3,13 14 15,30 6 15 29,30 2,19,21 25,26 1,24,25, Nagaland 1,26 1,14 26 15 2,29,30 2,19 4 26,27 2,19,28, Odisha 26 1,24 13 1,4,14 15,25,26 14,15,25 1,2,5,19 25 30 Puducherry 14,16,26 1,14 1 26^ 15,16,25 1^,29 2,18 1 2^,25 Punjab 5.26 10 13 1,4 29 26 15 30 2,5,19 4 25 Rajasthan 26 13 1,4,9,14 26^ 7,15 2^,30 1^,2,19,20 4 25 Sikkim 1,14,26 -

CAPITAL MARKET SEGMENT Download Ref No : NSE/CMTR/31297 Date : December 07, 2015 Circular Ref

NATIONAL STOCK EXCHANGE OF INDIA LIMITED DEPARTMENT : CAPITAL MARKET SEGMENT Download Ref No : NSE/CMTR/31297 Date : December 07, 2015 Circular Ref. No : 73/2015 All Members, Trading holidays for the calendar year 2016 In pursuance to clause 2 of Chapter IX of the Bye-Laws and Regulation 2.3.1 of part A Regulations of the Capital Market Segment, the Exchange hereby notifies trading holidays for the calendar year 2016 as below: Sr. No. Date Day Description 1 January 26, 2016 Tuesday Republic Day 2 March 07, 2016 Monday Mahashivratri 3 March 24, 2016 Thursday Holi 4 March 25, 2016 Friday Good Friday 5 April 14, 2016 Thursday Dr. Baba Saheb Ambedkar Jayanti 6 April 15, 2016 Friday Ram Navami 7 April 19, 2016 Tuesday Mahavir Jayanti 8 July 06, 2016 Wednesday Id-Ul-Fitr (Ramzan ID) 9 August 15, 2016 Monday Independence Day 10 September 05, 2016 Monday Ganesh Chaturthi 11 September 13, 2016 Tuesday Bakri ID 12 October 11, 2016 Tuesday Dasera 13 October 12, 2016 Wednesday Moharram 14 October 31, 2016 Monday Diwali-Balipratipada 15 November 14, 2016 Monday Gurunanak Jayanti The holidays falling on Saturday / Sunday are as follows: Sr. No. Date Day Description 1 May 01, 2016 Sunday Maharashtra Day 2 October 02, 2016 Sunday Mahatma Gandhi Jayanti 3 October 30, 2016 Sunday Diwali-Laxmi Pujan* 4 December 25, 2016 Sunday Christmas *Muhurat Trading will be conducted on Sunday, October 30, 2016. Timings of Muhurat Trading shall be notified subsequently. For and on behalf of National Stock Exchange of India Limited Khushal Shah Chief Manager Toll Free No Fax No Email id 1800 266 00 53 +91-22-26598155 [email protected] Regd. -

Vishwa Hindu Parishad (UK) World Council of Hindus Charity No: 262684

Vishwa Hindu Parishad (UK) World Council of Hindus Charity No: 262684 ON THIS SACRED MAHotSAVA WE WISH YOU Shubh Deepawali & Nutan Varshabhinandan (HAPPY DEEPAWALI & PROSPEROUS VIKRAM NEW YEAR) This heralds the Hindu New Year. Through several millennia of civilisation, Hindu Dharma has enhanced World Thought, Culture, Science & Peace (According to Sacred Hindu Scriptures) Bhagwan Shree Rama - Treta Yug - 1,296,000 human or 3,600 divine years – Bhagwan Shree Krishna – Dvapar Yug | 3228 BC - 3102 BC | Bhagwan Shree Buddha | 623 BC - 543 BC | Bhagwan Shree Mahavir | 599 BC – 527 BC | Vikram Samvat | 57-56 BC | Lord Christ | 0 BC/AD | Guru Nanak Dev Maharaj Ji (Nanak Shahi) | 1469 AD -1539 AD | \ Let us all remain guided eternally by SANATAN DHARMIC values, which are inclusive & plural, commonly known as Hindutva \ Ekam Sat Vipraha, Bahudha Vadanti \ (Truth is One, Wisemen (Seers, Rishis) have called it by different Names in different Eras) \ Sarve Bhavantu Sukhinaha, Sarve Santu Niramayaha, Sarve Bhadrani Pashyantu, Maakashchit Dukhabhag Bhavet \ (Let All be Happy, Let All be without Any illness, Let there be Universal Brotherhood, \ Vishwa Dharma Prakashena Vishwa Shanti Pravartake \ (Dharma - the Eternal Guiding Light for Universal Welfare and Peace) \ Asato ma Sad Gamaya - Lead me from Untruth to Truth \ Tamaso ma Jyotir Gamaya - Lead me from Darkness to Light Mrutyor ma Amritam Gamaya - Lead me from Death to Immortality \ Shanti Shanti Shantihi : \ Vishwa Hindu Parishad (UK) - World Council of Hindus & National Hindu Students Forum (NHSF) UK SPECIAL MESSAGE: On this auspicious occasion, come, let us rededicate ourselves towards, Spreading Universal Dharma of Righteousness, Peace & Conservation, keeping in mind the pollution generated as a result of the smoke from fireworks…. -

Applied For, Diary No. 48684/2014-CO/L Booklet Available

Self Published Booklet ISBN: Applied For Copyright: Applied For, Diary No. 48684/2014-CO/L Booklet available at: www.indiaholidaylist.com Your suggestions for the improvement of the booklet will always be welcome PREFACE Holidays were fun in our childhood days and as a school goer kid I remember that going through the holiday list was the first thing I used to do on receiving the school diary. However, as a professional, holidays have got a different meaning. I came across several consultants & dealers who constantly complain that they didn’t knew about the holidays in advance or they forgot to keep this in mind due to which their work gets substantially delayed. Consultants as well as Companies now a day are operating Pan India and they are having presence in almost all the States of India. In these circumstances, it becomes imperative for them to keep a track of the holidays in the States in which they are present. This booklet is meant for all such end- users, although its use is not limited to them. I hope this booklet will achieve its objective of making its end users to plan things ahead. My goal will be accomplished if this booklet helps you in avoiding at least one unproductive day. The sources for the compilation for most of the States are the Official Notification by the respective States/UT; however, for some of the other States/UT such Official Notification was not available. Compilation for these States/UTs has been done from other unofficial sources. Acknowledgements: First & foremost I extend my gratitude to my parents, friends & well wishers. -

Under Government Orders

(Under Government Orders) BOMBAY PlUNTED AT THE GOVERNMENT CENTlUI. PRESS )btainable from the Government Publications Sales Depot, Institute of Science ' Building, Fort, Bombay (for purchasers in Bombay City); from the Government Book Depot, Chami Road Gardens, Bombay 4 (for orders from the mofussil) or I through the High Commissioner for India, India House, Aldwych, London. W.C.2 . or through any recognized Bookseller. Price-Re. 11 Anna.s 6 or 198. 1954 CONTENTS 1lJ. PAGB PREFACE v GENERAL INTRODUCTION • VII-X MAP. PART I. CHAPTER 1 : PHYSICAL FEATURES .urn NATURAL REsOURCES- 1 Boundaries and Sub-Divisions 1 ; ASpects 2 ; Hills 4 ; River Systems 6; Geology 10 ; Climate 11; Forests 20; Fauna 24 ; Birds 28; Fish 32; Snakes 37. PART n. CHAPTER 2: ADMINISTRATIVE HISTORY- ,(1 Hindu Period ~90 B.C.-1295 A.D.) 41; Muslim Period (1295-1720) 43; Maratha Period \1720-1818) 52; British Period (1819-1947) 59. PART m. CIIAPTE~ 3: TIm, ~OPLE .AND Tm:m CULTURE-.- 69 Population' (1951 Census) 69; Food 75; Houses and Housing 76; Dress 78; Ornaments 21 ; Hindu CUstoms 82 ; Hindu Religious Practices 120;. Gaines 137; Dances 141; Akhadas or TaIims 145; ·Tamasha 146; Bene Israels'147; Christians 150; Muslims 153 ~ People from Tamil Nad 'and Kerala 157; Sindhi Hindus, 159. P~T IV....iECONOMIC ORGAN1ZAT~ON. CHAPTER 4: GENERAL ECONOMIC SURVEY .. 163 CHAPTER 5 : A~CULTUllE- 169 Agricultural .Popillation 169.; Rainfall 172; 'Agricultural Season 173; Soils 174; Land Utilization 177 j Holdings 183; Cereals 191; Pulses 196; Oil-Seeds 199; Drugs and Narcotics 201; Sugarcane 202; Condiments and Spices 204; Fibres 206; Fruits and Vegetables 207; AgricUltural. -

The Cultural Importance of the Arts

THE MEANING OF THE HINDU TEMPLE FOR THE NORTH INDIAN COMMUNITY IN VANCOUVER by Niranjan Anil Garde A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ADVANCED STUDIES IN ARCHITECTURE in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) May 2014 © Niranjan Anil Garde, 2014 Abstract This research study asks how the North Indian community in Vancouver gives meaning to its Hindu temple. It examines how community identity is expressed through the built environment of the temple. In order to understand the meaning attributed to the Hindu temple by the North Indian community, I undertook an ethnographic case study of a Hindu temple in the city of Surrey, Greater Vancouver Region. The study is also a personal journey through which I have come to understand the built environment as an expression of identity. The research study claims that the meaning of the built environment is related to how one perceives it – which depends on one’s values, which in turn, are related to the context. Such a study offers an important contribution to knowledge about how North Indians use their temples in a diasporic context. It also suggests that the study of this kind of architecture is dependent on the community’s perceptions and meanings. ii Preface This dissertation is an original intellectual product of the author, Niranjan Anil Garde. The methodology reported in Chapter 1, the access to the fieldwork and the data collected according to the prescribed forms as mentioned in appendix 4 was covered under the approval of UBC Ethics Certificate number H13-01590. -

Hyderabad Bangalore

HYDERABAD Fixed Weekly Offs: Saturdays and Sundays S.No. Date Day of the Week Holiday 1 Jan 13, 2017 Friday Bhogi/Makar Sankranti/Pongal/Lohri 2 Jan 26, 2017 Thursday Republic Day 3 Mar 29, 2017 Wednesday Ugadi/Gudi padva 4 Jun 2, 2017 Friday Telangana/AP formation day 5 Jun 26, 2017 Monday Ramzaan Eid/Eid-ul-Fitr 6 Aug 15, 2017 Tuesday Independence Day 7 Aug 25, 2017 Friday Ganesh Chaturthi 8 Oct 2, 2017 Monday Gandhi Jayanti 9 Oct 18, 2017 Wednesday Diwali (Balipratipada/Padwa) 10 Dec 25, 2017 Monday X'mas With Staggered Weekly Offs S.No. Date Day of the Week Holiday 1 Jan 14, 2017 Saturday Makar Sankranti/Pongal/Lohri 2 Jan 26, 2017 Thursday Republic Day 3 Mar 29, 2017 Wednesday Ugadi/Gudi padva 4 Jun 26, 2017 Monday Ramzaan Eid/Eid-ul-Fitr 5 Aug 15, 2017 Tuesday Independence Day 6 Aug 25, 2017 Friday Ganesh Chaturthi 7 Sep 30, 2017 Saturday Dassera/Vijaya Dashmi/Ayudh Pooja 8 Oct 2, 2017 Monday Gandhi Jayanti 9 Oct 18, 2017 Wednesday Diwali (Balipratipada/Padwa) 10 Dec 25, 2017 Monday X'mas BANGALORE Fixed Weekly Offs: Saturdays and Sundays S.No. Date Day of the Week Holiday 1 Jan 13, 2017 Friday Bhogi/Makar Sankranti/Pongal/Lohri 2 Jan 26, 2017 Thursday Republic Day 3 Mar 29, 2017 Wednesday Ugadi/Gudi padva 4 Jun 26, 2017 Monday Ramzaan Eid/Eid-ul-Fitr 5 Aug 15, 2017 Tuesday Independence Day 6 Aug 25, 2017 Friday Ganesh Chaturthi 7 Oct 2, 2017 Monday Gandhi Jayanti 8 Oct 18, 2017 Wednesday Diwali (Balipratipada/Padwa) 9 Nov 1, 2017 Wednesday Kannada Rajyotsava 10 Dec 25, 2017 Monday X'mas NOIDA Fixed Weekly Offs: Saturdays and Sundays S.No. -

About Deepawali - the Social Significance

About Deepawali - The Social Significance Deepa means a lamp and avali means a row. The word literally means a row of lights. We normally think that Deepawali is about a lamplight, a deepa. In fact, Deepawali is not about a single deepa, it is about many. It is about a collective, an organization, a formation of lamps. It is about the relationship between one lamp and the rest of the lamps in the collective. The secret message of deepawali is hidden in its very name. Let us begin with a short prayer that sums up the essence of this remarkable festival. Deepawali Prayer Om Asato Maa Sat Gamaya Tamaso Maa Jyotir Gamaya Mrityor Maa Amritam Gamaya Sat means the truth and a-sat is its negation or falsehood. So the first line means: lead me from Falsehood to Truth. Tamas is darkness or ignorance. And jyoti is light. So the second line means: lead me from darkness or ignorance to light or knowledge. The third line means lead me from death (mtriyu ) to immortality (amrita). Deepawali is the festival of lights symbolizing the lighting of the lamp of knowledge and removing ignorance, in our lives, and in those of others. It is this deeper message of social consciousness behind the glamour of Deepawali that this article attempts to convey. The Diya - Lamp The central theme behind deepawali rests on the concept of the Diya, the lamp. In Hindu tradition Ishwara or God is the "Knowledge principle," the Reality, the source of all knowledge. The light enables one to see the reality that is ever present. -

Listofholidays2020 0.Pdf

ANNEXURE - I LIST OF PUBLIC HOLIDAYS DURING THE YEAR 2O2O FOR CENTRAL GOW. OFFICES SITUATED IN THE STATE OF MAHARSHTRA Date Day SNo. L Holiday Sunday 1 Republic Day 26.0 i.2020 2 Holi 10.03.2020 Tuesday J Gudi Padwa 2s.03.2020 Wednesday 4 Mahavir Jayanti 06.04.2020 tulonday Friday 1.0.04.2020 Friday ls Good Thursday D Buddha Purnima 07.05.2020 * 7 IdtIl Fitr 25.05.2020 Monday * Saturday B ldr]l Zuha (Bakri Id) 01.08.2020 Wednesda 9 Janamashtami Vaishnavi 12.08.2020 10 Independence DaY 15.08.2020 Saturday * 11 Muharram 30.08.2020 Sunday i1 2 Mahatma Gandhls Bifthday 02.10.2020 Friday 1) Dussehra (Vijay Dashmi) 2s.70.20?-0 Sunday x 74 Prophet Mohammads 30.10.2020 Friday Bifthday(Id-e-Milad) 15 Diwali (Deepavali) 14.11.2020 Saturday Monday i1 6 Guru NanaKs Birthday 30.11.2020 T7 Christmas'Day 25.12.2020 Frida ___ subject to * Based on holiday declared bY Govt. of Maharashtra and would be change as per decision of Govt, of Maharashtra. tJ ,tr" (PADMAKUMARAN.C ) Jt. S-ecretary, CGEWCC, Mumbai. ANNEXURE II RESTRICTED HOLIDAYS FOR THE YEAR 2O2O TO BE OBSERVED BY CENTRAL GOVERNMENT OFFICES IN MAHARASHTRA STATE S.No. Name of the Holiday Date Dav 1 New Year's Day January,01 Wednesdav ,) Guru Gobind Sinqh's Birthday January, 02 Thu rsday Lohri January, '13 Monday 4 Makar Sankranti / Pongal January, 15 Wednesday 5 Shri Ganesh Jayanti January,2E Tuesday 6 Basant Panchami / Sri Panchami January,30 Thursday 7 Guru Ravidas's Birthday February, 09 Sunday B Swami Dayananda Saraswati Ja anti February, 18 Tuesday 9 Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Jayanti February, 19 Wednesday '10 Mahashivratri F ebruary , 21 Friday 1'1 Holika Dahan / Dol atra I Hazarat Ali's Brrthda March,09 Monday Shri Ram Navami April, 02 Thursday IJ Hanuman.layanti April, 08 Wednesday 14 Pesach (Jew) April, 09 Thursday 15 Easter Sunday April, 12 Su nday 10 Vaisakhi/ Vishu April, 13 Monday 17 Or. -

STUDENT RESOURCE BOOK (2018-19) Part-I

STUDENT RESOURCE BOOK (2018-19) Part-I NMIMS Hyderabad Dr. Prithvi Yadav Ms. Vandana Kushte Mr. Ashish Apte (Director) (Deputy Registrar – Academics) (Controller of Exam) Dr. Meena Chintamaneni Dr. Sharad Mhaiskar Dr. Rajan Saxena (Registrar) (Pro Vice Chancellor) (Vice Chancellor) Message from Vice Chancellor Congratulations! You are one of the privileged student, who has been selected at NMIMS. You have joined the University which has been the education and training ground of some of the most distinguished and outstanding professionals, academic leaders and CEOs. You are also privileged, as you will have an outstanding learning environment built assiduously over the years by the faculty and staff. I am sure, NMIMS education will have a profound impact on your thinking and choices in life. As a University, we value the intellect you bring to the program. I am sure you will play an important role in generating new ideas that will transform human lives and the society. Over the years, NMIMS has grown to being a multi-faculty and multi-campus Category I university. This has enabled university to innovate and encourage the growth of holistic education at the undergraduate level. It has also encouraged the University to offer interdisciplinary courses at the Master’s level. The University is committed to building more flexible structures in Academic Programs, delivery models and assessment technology. We are also committed to engage with you in multiple ways, using classroom and non-classroom activities and technology. The legacy of this University is built on four pillars, namely Innovation, Market Responsiveness, Discovery and Employability. Also ethos of `giving’ combined with `integrity’ is engrained in NMIMS. -

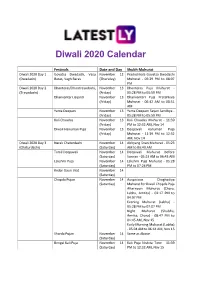

Diwali 2020 Calendar

Diwali 2020 Calendar Festivals Date and Day Shubh Muhurat Diwali 2020 Day 1 Govatsa Dwadashi, Vasu November 12 Pradoshkala Govatsa Dwadashi (Dwadashi) Baras, Vagh Baras (Thursday) Muhurat - 05:29 PM to 08:07 PM Diwali 2020 Day 2 Dhanteras/Dhantrayodashi, November 13 Dhanteras Puja Muhurat - (Trayodashi) (Friday) 05:28 PM to 05:59 PM Dhanvantari Jayanti November 13 Dhanvantari Puja Pratahkala (Friday) Muhurat - 06:42 AM to 08:51 AM Yama Deepam November 13 Yama Deepam Sayan Sandhya - (Friday) 05:28 PM to 05:59 PM Kali Chaudas November 13 Kali Chaudas Muhurat - 11:39 (Friday) PM to 12:32 AM, Nov 14 Diwali Hanuman Puja November 13 Deepavali Hanuman Puja (Friday) Muhurat - 11:39 PM to 12:32 AM, Nov 14 Diwali 2020 Day 3 Narak Chaturdashi November 14 Abhyang Snan Muhurat - 05:23 (Chaturdashi) (Saturday) AM to 06:43 AM Tamil Deepavali November 14 Deepavali Muhurat before (Saturday) Sunrise - 05:23 AM to 06:43 AM Lakshmi Puja November 14 Lakshmi Puja Muhurat - 05:28 (Saturday) PM to 07:24 PM Kedar Gauri Vrat November 14 (Saturday) Chopda Pujan November 14 Auspicious Choghadiya (Saturday) Muhurat for Diwali Chopda Puja Afternoon Muhurat (Chara, Labha, Amrita) - 02:17 PM to 04:07 PM Evening Muhurat (Labha) - 05:28 PM to 07:07 PM Night Muhurat (Shubha, Amrita, Chara) - 08:47 PM to 01:45 AM, Nov 15 Early Morning Muhurat (Labha) - 05:04 AM to 06:44 AM, Nov 15 Sharda Pujan November 14 Same as Above (Saturday) Bengal Kali Puja November 14 Kali Puja Nishita Time - 11:39 (Saturday) PM to 12:32 AM, Nov 15 Diwali 2020 Day 4 Govardhan Puja/Annakut November -

Diwali Festival in Maharashtra

Diwali Festival in Maharashtra The Hindu festival of Diwali is the celebration of lights and is observed in India as well as in other countries. The specialty of the occasion is the festivities wherein, the houses are decorated with attractive lights and there is also the most important part of bursting the fire crackers. Celebrated since the ancient times, the festival of Diwali is about the victory of good over bad and hence the lights symbolize the removal of evil from lives and welcoming happiness, joy and prosperity. The concept of light over darkness is seen due to an ancient story about the Gods. This is one of the grandest festivals celebrated in the country. The lamps that are placed in the houses are meant to welcome goddess Lakshmi into their home and bless them with ample prosperity and wealth. According to the people of Maharashtra, in the archetypal Marathi family diwali starts from 'Vasu-baras' which happens to fall on 'Ashwin Krishna Dwadashi' date according to the Marathi calendar. This includes a celebration held in respect of cows that are considered as a mother in the Hindu religion in every part of India. The employees get bonuses and holidays to spend time celebrate this auspicious festival with friends and family. The bonuses are generally used for buying new things in the houses and for the people. The stores usually have offer and schemes to attract the customers during the festive season because evidently everybody is out for shopping. HISTORY OF THE ATTRACTION Diwali is celebrated in honor of the auspicious occasion when Lord Rama, his wife Sita and his brother Lakshmana returned back from an exile of 14 years.