African Americans and Soul Foods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abstract Nobles, Currey Allen

ABSTRACT NOBLES, CURREY ALLEN. Processing Factors Affecting Commercially Produced Pork Bacon. (Under the direction of Dana J. Hanson.) Three studies were performed to assess the effects of processing and ingredient parameters on the production yields and consumer acceptance of pork bacon. Products were produced at a commercial processing facility and processed under standard plant procedures. Study 1 was conducted to assess the effect of sodium phosphate reduction on processing yields and consumer sensory perception of bacon. Standard sodium phosphate level bacon (SP) and low sodium phosphate level bacon (LP) were produced at a commercial bacon processing facility. The SP bacon was formulated to 0.05% sodium phosphate in the finished product. LP bacon was formulated to 0.005% sodium phosphate in the finished product. SP bacon trees (N=9; 575 individual pork bellies) and LP bacon trees (N=9; 575 individual pork bellies) were produced. Phosphate reduction had no effect (p>0.05) on smokehouse and cooler yields. Phosphate reduction also showed no effect (p>0.05) on yield of #1 and #2 bacon slices. At 30 days post processing consumers rated LP bacon higher than SP bacon (p<0.05) in the attribute of overall liking, but there was no clear preference (p>0.05) of either product among consumers. At 110 days post processing SP bacon was rated higher by consumers (p<0.05) than LP bacon in the attribute of overall flavor liking, but there was no clear preference (p>0.05) for either product. Sodium phosphate reduction was not detrimental to processing yields and still produced a product that was well received by consumers. -

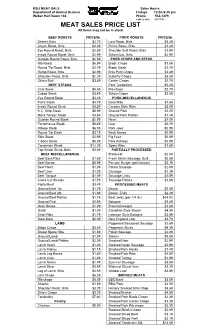

MEAT SALES PRICE LIST All Items May Not Be in Stock

KSU MEAT SALE Sales Hours: Department of Animal Science Fridays 12:00-5:45 pm Weber Hall Room 166 Phone 532-1279 expires date 05/31/05 MEAT SALES PRICE LIST All items may not be in stock BEEF ROASTS PRICE/lb. PORK ROASTS PRICE/lb. Brisket, Bnls $2.79 Loin Roast, Bnls $3.49 Chuck Roast, Bnls $2.39 Picnic Roast, Bnls $1.49 Eye Round Roast, Bnls $2.89 Shoulder Butt Roast, Bnls $1.59 Inside Round Roast, Bnls $2.99 Sirloin Butt, Bnls $2.99 Outside Round Roast, Bnls $2.59 PORK CHOPS AND STEAK Rib Roast $8.99 Blade Chops $1.89 Round Tip Roast, Bnls $2.79 Blade Steak $1.79 Rump Roast, Bnls $2.99 Bnls Pork Chops $3.69 Shoulder Roast, Bnls $2.29 Butterfly Chops $3.69 Sirloin Butt $3.89 Center Chops $2.79 BEEF STEAKS Pork Tenderloin $5.29 Club Steak $5.69 Rib chops $2.79 Cubed Steak $3.49 Sirloin Chops $2.09 Eye Round Steak $3.49 PORK-MISCELLANEOUS Flank Steak $4.79 Back Ribs $1.69 Inside Round Steak $3.29 Country Style Ribs $2.09 K.C. Strip Steak $6.69 Ground Pork $1.29 Mock Tender Steak $3.69 Ground Pork Patties $1.49 Outside Round Steak $2.99 Heart $1.09 Porterhouse Steak $6.49 Liver $0.79 Ribeye Steak $6.59 Pork Jowl $0.99 Round Tip Steak $3.19 Neck Bones $0.99 Skirt Steak $2.99 Pig Feet $0.89 T-bone Steak $6.39 Pork Kidneys $0.99 Tenderloin Steak $12.29 Spare Ribs $1.89 Top Sirloin Steak, Bnls $3.89 PARTIALLY PROCESSED BEEF-MISCELLANEOUS Bratwurst $2.69 Beef Back Ribs $1.69 Fresh Italian Sausage, Bulk $2.89 Beef Bones $0.99 Por-con Burger (pork-bacon) $2.19 Beef Heart $1.09 Potato Sausage $2.69 Beef Liver $1.09 Sausage $1.39 Beef Tongue $1.69 -

Uniform Retail Meat Identity Standards a PROGRAM for the RETAIL MEAT INDUSTRY APPROVED NAMES PORK

Uniform Retail Meat Identity Standards A PROGRAM FOR THE RETAIL MEAT INDUSTRY APPROVED NAMES PORK This section is organized in the following order: SELECT AN AREA TO VIEW IT Species Cuts Chart LARGER SEE THE Species-Specific FOLLOWING Primal Information AREAS Index of Cuts Cut Nomenclature PORK -- Increasing in and U.P.C.Numbers Popularity Figure 1-- Primal (Wholesale) Cuts and Bone Structure of Pork Figure 2 -- Loin Roasts -- Center Chops INTRODUCTION Figure 3 -- Portion Pieces APPROVED NAMES -- Center Chops BEEF Figure 4-- Whole or Half Loins VEAL PORK Figure 5 -- Center Loin or Strip Loin LAMB GROUND MEATS Pork Belly EFFECTIVE MEATCASE MANAGEMENT & Pork Leg FOOD SAFETY MEAT COOKERY Pork Cuts GLOSSARY & REFERENCES Approved by the National Pork Board INDUSTRY-WIDE COOPERATIVE MEAT IDENTIFICATION STANDARDS COMMITTEE Uniform Retail Meat Identity Standards A PROGRAM FOR THE RETAIL MEAT INDUSTRY APPROVED NAMES PORK INTRODUCTION APPROVED NAMES BEEF VEAL PORK LAMB GROUND MEATS EFFECTIVE MEATCASE MANAGEMENT FOOD SAFETY MEAT COOKERY GLOSSARY & REFERENCES INDUSTRY-WIDE COOPERATIVE MEAT IDENTIFICATION STANDARDS COMMITTEE Uniform Retail Meat Identity Standards A PROGRAM FOR THE RETAIL MEAT INDUSTRY APPROVED NAMES PORK INTRODUCTION APPROVED NAMES BEEF VEAL PORK LAMB GROUND MEATS EFFECTIVE MEATCASE MANAGEMENT FOOD SAFETY MEAT COOKERY GLOSSARY & REFERENCES INDUSTRY-WIDE COOPERATIVE MEAT IDENTIFICATION STANDARDS COMMITTEE Uniform Retail Meat Identity Standards A PROGRAM FOR THE RETAIL MEAT INDUSTRY APPROVED NAMES PORK INTRODUCTION APPROVED NAMES BEEF -

Canadian Pork Buyers Guide

CANADIAN PORK BUYERS’ GUIDE PORK SHOULDER PORK LOIN PORK LEG PORK BELLY PORK RIBS LOIN, BACK RIBS CPI#C505 BELLY, RIB IN CPI#C410 SHOULDER, BLADE (BUTT) SHOULDER, PICNIC, LOIN, BONE-IN CPI#C200 LOIN, BONELESS CPI#C201 CPI#C320 HOCK-ON CPI#C310 LEG (FRESH HAM) CPI#C100 LEG (FRESH HAM), FLANK REMOVED CPI#C101 BELLY, SIDE RIBS CPI#C500 BELLY, SKINLESS CPI#400 BUYERS’ GUIDE SHOULDER, BLADE (BUTT), SHOULDER PICNIC, BONELESS, LOIN, RIB RACK, NINE BONE, LOIN, SHORT CUT BACK, BONELESS CPI#C325 GLOVE CUT STYLE CPI#C316 FRENCHED CPI#C210 BONELESS CPI#205 LEG (FRESH HAM), BONELESS, LEG (FRESH HAM), BONELESS, FOUR PIECE SKINLESS CPI#C105 (INSIDE, OUTSIDE, KNUCKLE, LIGHT BUTT) CPI#110 BELLY, SIDE RIBS, BREAST BONE RETAIL AND FOODSERVICE END-USER GUIDE REMOVED CPI#C501 BELLY, SKINLESS, SQUARE CUT CPI#401 BELLY, SIDE RIBS, CENTRE CUT CPI#C502 SHOULDER, BLADE (BUTT,) SHOULDER, PICNIC, LOIN, SHORT CUT BACK, BONELESS, FALSE LEAN AND BELLY LOIN, SHORT CUT BACK, BONELESS, CAPICOLA, BONELESS CPI#C330 BONELESS CPI#C315 STRIP REMOVED CPI#C209 MAIN MUSCLE CPI#C211 LEG (FRESH HAM), INSIDE, LEG (FRESH HAM), OUTSIDE, LEG (FRESH HAM), KNUCKLE, BONELESS CPI#C107 BONELESS CPI#C106 BONELESS CPI#C108 BELLY, SKINLESS, SINGLE RIBBED CPI#C405 BRISKET BONE CPI#C821 WWW.VERIFIEDCANADIANPORK.COM SHOULDER, PICNIC, FRONT SHANK MEAT, SHOULDER, PICNIC, CUSHION, LOIN, TENDERLOIN LOIN, RIB CAP (FALSE LEAN) LOIN, SIRLOIN BELLY, SKINLESS, SINGLE RIBBED, SHOULDER, RIBLETS, LOIN, BUTTON BONES PECTORAL MEAT CPI#C346 BONELESS CPI#C319 BONELESS CPI#C345 CPI#C227 CPI # 229 CPI#C235 LEG -

LEARNING KIT MEAT PROCESSING CAVA PROJECT (Erasmus+ 2014 Call for Proposal - Code 2014-1-IT01-KA202-002680) DIDACTIC UNIT (1-4) UNIT 1: Meat Definition

With the support of the Erasmus+ program of the European Union LEARNING KIT MEAT PROCESSING CAVA PROJECT (Erasmus+ 2014 Call for proposal - Code 2014-1-IT01-KA202-002680) DIDACTIC UNIT (1-4) UNIT 1: meat definition UNIT 2: meat origin UNIT 3: structure of animal tissues and organs; connective tissue; offal UNIT 4: chemical composition of meat • Meat is food of animal origin, i.e. obtained by slaughter of livestock or by shooting or slaughtering wild game. • From culinary point of view: all muscle edible parts of animals. • The definition of meat may be wider or narrower, depending on what the term “meat” encompasses. In the wider sense, meat comprises all body tissues of slaughtered warm-blooded animals suitable for human consumption, including offal, adipose tissue, and blood. MEAT DEFINITION In a narrower sense, meat are muscles (muscle tissue) and bone base linked together by adipose and connective tissue. • Meat is easily perishable and therefore it can be kept in a state suitable for human consumption for only a short period of time. • In order to extend the meat keepability, different preserving and processing procedures are applied aiming at impeding, limiting or directing the microorganisms and tissue enzymes' activity and protecting the nutritional value of meat. • Moreover, the objective is to improve the organoleptic properties of meat and meat products. • The market offers fresh meat, refrigerated meat, frozen meat, MEAT DEFINITION semi-processed and processed meat, i.e. dried, smoked, sausages or salami, canned and cured meat cuts. • Slaughtering and primary carcass processing result in obtaining edible parts and secondary slaughter products. -

Dudley Poultry, Co

Dudley Poultry, Co. PRODUCT CATALOGUE 800-648-6881 910 STATE ROUTE 245 | MIDDLESEX, NY 14507 WWW.DUDLEYPOULTRY.COM Beef |Pork |Poultry |Seafood |Appetizers & More! Contents Appetizers ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Beef Fresh ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Beef (Frozen) ................................................................................................................................. 10 Beverages ...................................................................................................................................... 12 Canned Beans ................................................................................................................................ 14 Canned Fruit ................................................................................................................................. 16 Canned Tomato ............................................................................................................................ 18 Canned Veg. .................................................................................................................................. 20 Charcoal ........................................................................................................................................ 22 Chicken Breaded .......................................................................................................................... -

Artisanal Charcutterie

ARTISANAL CHARCUTTERIE LIST OF PRODUCTS & DESCRIPTION Guanciale Guanciale is an Italian cured meat product prepared from pork jowl or cheeks. Its name is derived from guancia, Italian for cheek. 520 THB/KG Its flavor is stronger than other pork products, such as pancetta, and its texture is more delicate. Upon cooking, the fat typically melts away giving great depth of flavor to the dishes and sauces it is used in. In cuisine Guanciale may be cut and eaten directly in small portions, but is often used as a pasta ingredient.It is used in dishes like spaghetti alla carbonara and sauces like sugo all'amatriciana. Coppa / Cabecero de lomo Capocollo or Coppa is a traditional Italian and Corsican pork cold cut (salume) made from the dry-cured muscle running from the neck to the 4th or 5th rib of the pork shoulder or neck. 1030 THB/ Kg It is a whole muscle salume, dry cured and, typically, sliced very thin. It is similar to the more widely known cured ham or prosciutto, because they are both pork-derived cold-cuts that are used in similar dishes This cut is typically called capocollo or coppa in much of Italy and Corsica. Regional terms include capicollo (Campania), capicollu (Corsica), finocchiata (Tuscany), lonza (Lazio) and lonzino (Marche and Abruzzo). Capocollo is esteemed for its delicate flavor and tender, fatty texture and is often more expensive than most other salumi. In many countries, it is often sold as a gourmet food item. It is usually sliced thin for use in antipasto or sandwiches such as muffulettas, Italian grinders and subs, and panini as well as some traditional Italian pizza. -

Guidelines for Slaughtering, Meat Cutting and Further Processing

04/11/2011 Guidelines for slaughtering, meat cutting and further proc… FAO ANIMAL PRODUCTION AND HEALTH PAPER 91 Guidelines for slaughtering, meat cutting and further processing Contents The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. D:/cd3wddvd/NoExe/Master/dvd001/…/meister10.htm 1/227 04/11/2011 Guidelines for slaughtering, meat cutting and further proc… M-72 ISBN 92-5-102921-0 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Publications Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Via delle Terme di Caracalla, 00 100 Rome, Italy. FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, © FAO 1991 Hyperlinks to non-FAO Internet sites do not imply any official endorsement of or responsibility for the opinions, ideas, data or products presented at these locations, or guarantee the validity D:/cd3wddvd/NoExe/Master/dvd001/…/meister10.htm 2/227 04/11/2011 Guidelines for slaughtering, meat cutting and further proc… of the information provided. The sole purpose of links to non-FAO sites is to indicate further information available on related topics. -

Effects of Dried Distillers Grains with Solubles (Ddgs

EFFECTS OF DRIED DISTILLERS GRAINS WITH SOLUBLES (DDGS) FEEDING STRATEGIES ON GROWTH PERFORMANCE, NUTRIENT INTAKE, BODY COMPOSITION, AND LEAN AND FAT QUALITY OF IMMUNOLOGICALLY CASTRATED PIGS HARVESTED AT 5, 7, or 9 WEEKS AFTER THE SECOND IMPROVEST® DOSE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Erin Kay Harris IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Gerald C. Shurson, Adviser December 2014 © Erin K. Harris 2014 Acknowledgements This thesis could not have been completed without the support and help of many people. My love for agriculture, food-producing animals, and pigs is only possible due to the enormous gift and blessing of growing up on a hog farm, where my early days included the stroller view of the farrowing barn and paint-stick wall art in the finishing barn. My parent’s dedication and perseverance through many challenges I’ve experienced are a gift, and provided me with perspective and instilled my core values. In addition, I could not have accomplished this without the left over meals from my mother and pep- talks from my father, who's first-hand experience of the Ph.D. process was invaluable and is an experience that few fathers anddaughters can relate. To my committee members, Dr. Jerry Shurson, Dr. Lee Johnston, Dr. Bill Dayton, Dr. Ryan Cox, and Dr. Marnie Mellencamp, thank-you for taking me on as graduate student, and providing opportunities to allow me to develop into a more well-rounded professional, and for challenging me outside of my academic comfort zone. -

Wholesale-Pork Catalog

TABLE OF CONTENTS Pork .................................................................................................................................................... 2 Bacon ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Ham ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Pork Belly ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Pork Bones .................................................................................................................................... 4 Pork Grinds ................................................................................................................................... 4 Pork Loin ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Pork Offal ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Pork Prepared Meats ..................................................................................................................... 7 Pork Shoulder ................................................................................................................................ 8 Whole Pig .................................................................................................................................... -

No-Guilt Pig-Out Recipes from Our Farm to Your Table

NO-GUILT PIG-OUT RECIPES FROM OUR FARM TO YOUR TABLE ã Mockingbird Farm INTRODUCTION I use recipes as inspiration, so I tend to write them that way, too. Use these adaptable recipes as guides to create dishes that you and your family will love. Onions don’t agree with me, so I don’t use them, but if you like them and they like you, most of these dishes will benefit from their flavor. Except the chocolate pecan pie. Don’t put onions in that. All of the recipes in this booklet are my own inventions, with the exception of a couple that I gained permission from the author to use. You’ll see notes on those and links to more from those authors. The recipes also are gluten-free / grain-free / Paleo-friendly. Each of these recipes is something that I’ve made multiple times. I seldom make a dish the same way twice, which is why it’s taken me ages to write this booklet. I wanted to make sure I’d made all of these recipes multiple times so that they’d work out great for you. Feedback is welcome – let me know what you think, what you love, if you want more information, or if something doesn’t work out for you. My email address is [email protected]. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Asian Pork Tacos Page 4 Bacon Jam Page 5 Fresh Pork Belly Page 6 Savory Pork Pie Page 7 Ground Pork Bake Page 8 Ground Pork Sautee Page 9 Braised Fresh Ham Roast Page 10 Braised Pork Jowl Page 11 Apple Juice Pork Shoulder Page 12 Slow Cooked Spare Ribs Page 13 Apple & Celeriac Remoulade Page 14 Cassava Flour Tortillas Page 15 Chocolate Pecan Pie Page 16 3 SHOPPING LIST Mockingbird -

Meatworks Pork Cutting Instructions

MEATWORKS PORK CUTTING INSTRUCTIONS (774) 319-5616 [email protected] HOURS OF OPERATION 7:00AM TO 4:00PM LIVESTOCK RECEIVING HRS MON-FRI 1:30PM TO 3:30PM SUNDAY 12:00PM TO 1:00PM CUSTOMER NAME FARM NAME PHONE # # OF ANIMALS PEN # KILL DATE ORDER # ANIMAL ID (S)/LIVE WEIGHT LOT #/CARCASS ID (S) THICKNESS: 1"__ 1.25"__ 1.5"__ ROAST WEIGHTS: 2-3LBS___ 3-4LBS___ 4-5LBS___ PORK SHOULDER *IF YOU SELECT SMOKE THE VALUE-ADDED SERVICE SECTION MUST BE COMPLETED CHECK ONE: 3168 WHOLE SKIN-ON___ 3172 ARM ROAST___ GRIND___ SMOKE___ SPECIAL INSTRUCIONS: PORK BUTTS *IF YOU SELECT SMOKE THE VALUE-ADDED SERVICE SECTION MUST BE COMPLETED CHECK ONE: 3184 ROAST___ 3186 BLADE STEAKS___ 3198 COUNTRY-STYLE RIBS____ SMOKE___ GRIND___ SPECIAL INSTRUCIONS: PORK HAMS *IF YOU SELECT SMOKE THE VALUE-ADDED SERVICE SECTION MUST BE COMPLETED CHECK ONE: 3402 CENTER CUT ROAST___ 3404 CENTER CUT STEAKS___ SMOKE___ GRIND___ SPECIAL INSTRUCIONS: PORK BELLY *IF YOU SELECT SMOKE THE VALUE-ADDED SERVICE SECTION MUST BE COMPLETED CHECK ONE: 3427 WHOLE SKIN-ON___ SMOKE___ 3468 SPARE RIBS YES ___ NO ___ SPECIAL INSTRUCIONS: PORK LOINS *IF YOU SELECT SMOKE THE VALUE-ADDED SERVICE SECTION MUST BE COMPLETED CHECK ONE: (RIB/LOIN/SIRLOIN): 3268/3266/3328 BI ROASTS___ 3298/3313/3338 BI CHOPS___ SMOKE___ GRIND___ SPECIAL INSTRUCIONS: GROUND PORK *IF YOU SELECT SAUSAGE THE VALUE-ADDED SERVICE SECTION MUST BE COMPLETED 5400 1-LB PKG___ 5401 2-LB PKG ___ 5403 5-LB PKG___SAUSAGE___ (50 LB MINIMUM PER SAUSAGE BATCH) SPECIAL INSTRUCIONS: PORK ORGAN MEAT *ALL ORGAN MEAT PASSING