Third Spot Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YS% ,Xld M%Cd;Dka;S%L Iudcjd§ Ckrcfha .Eiü M;%H the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

YS% ,xld m%cd;dka;s%l iudcjd§ ckrcfha .eiÜ m;%h The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka wxl 1"991 – 2016 Tlaf;dan¾ ui 28 jeks isl=rdod – 2016'10'28 No. 1,991 – fRiDAy, OCtOBER 28, 2016 (Published by Authority) PART I : SECTION (I) – GENERAL (Separate paging is given to each language of every Part in order that it may be filed separately) PAGE PAGE Proclamations, &c., by the President … — Government Notifications … … 1204 Appointments, &c., by the President … 1128 Price Control Orders … … — Appointments, &c., by the Cabinet of Ministers … — Central Bank of Sri Lanka Notices… … — Accounts of the Government of Sri Lanka … — Appointments, &c., by the Public Service Commission — Revenue and Expenditure Returns… … — Appointments, &c., by the Judicial Service Commission — Miscellaneous Departmental Notices … 1206 Other Appointments, &c. … … 1192 Notice to Mariners … … — Appointments, &c., of Registrars … — “Excise Ordinance” Notices … … — Note.– (i) Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Bill was published as a supplement to the part ii of the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka of August 12, 2016. (ii) Nation Building tax (Amendment) Bill was published as a supplement to the part ii of the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka of August 19, 2016. (iii) Land (Restrictions on Alienation) (Amendment) Bill was published as a supplement to the part ii of the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka of September 02, 2016. IMportant NOTICE REGARDING Acceptance OF NOTICES FOR PUBlication IN THE WEEKLY “GAZETTE” AttENtiON is drawn to the Notification appearing in the 1st week of every month, regarding the latest dates and times of acceptance of Notices for publication in the weekly Gazettes, at the end of every weekly Gazette of Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. -

2013 Titled “Sri Lanka As a Hub in Asia: the Way Forward”

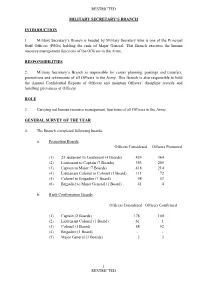

RESTRICTED MILITARY SECRETARY’S BRANCH INTRODUCTION 1. Military Secretary‟s Branch is headed by Military Secretary who is one of the Principal Staff Officers (PSOs) holding the rank of Major General. This Branch executes the human resource management functions of the Officers in the Army. RESPONSIBILITIES 2. Military Secretary‟s Branch is responsible for career planning, postings and transfers, promotions and retirements of all Officers in the Army. This Branch is also responsible to hold the Annual Confidential Reports of Officers and maintain Officers‟ discipline records and handling grievances of Officers. ROLE 3. Carrying out human resource management functions of all Officers in the Army. GENERAL SURVEY OF THE YEAR 4. The Branch completed following boards: a. Promotion Boards. Officers Considered Officers Promoted (1) 2/Lieutenant to Lieutenant (4 Boards) 424 364 (2) Lieutenant to Captain (7 Boards) 393 205 (3) Captain to Major (7 Boards) 418 214 (4) Lieutenant Colonel to Colonel (1 Board) 111 72 (5) Colonel to Brigadier (1 Board) 98 57 (6) Brigadier to Major General (1 Board) 41 4 b. Rank Confirmation Boards. Officers Considered Officers Confirmed (1) Captain (2 Boards) 178 100 (2) Lieutenant Colonel (1 Board) 61 1 (3) Colonel (1 Board) 58 52 (4) Brigadier (1 Board) - - (5) Major General (3 Boards) 3 3 1 RESTRICTED RESTRICTED c. Selection of Officers for Selected Majors List (1 Board): Officers Considered Officers Selected Major 129 60 5. Further to above, this Branch published the Officers Seniority list for 2014. ACHIEVEMENTS 6. Overall co-ordination of the Second Army Symposium 2013 titled “Sri Lanka as a Hub in Asia: the Way Forward”. -

Kamal Gunaratne Secretary of Defence Sri Lanka

KAMAL GUNARATNE SECRETARY OF DEFENCE SRI LANKA Dossier December 2019 1 MAJOR GENERAL (RET.) GABADAGE DON HARISCHANDRA KAMAL GUNARATNE 53 Division Commander in 2009 Currently Secretary of Defence and Sri Lankan Army Reserve Force. 2 SUMMARY Sri Lanka’s new secretary of defence commanded one of the most important military divisions in the 2009 war in the Vanni when the United Nations says there are reasonable grounds to say war crimes were committed by the men under his command. It is noteworthy that though appointed to a civilian post, he received a military parade at his inauguration1 and remains in the Army’s Reserve Force2. He went on to run Sri Lanka’s most notorious army torture camp in Vavuniya for 18 months after the war at a time of mass detention. The ITJP has documented ten accounts of torture and/or sexual violence committed by soldiers against detainees in that period and this is likely the tip of the iceberg. There is no way as the camp commander he could not have known about detention there – this was not a legal detention site but contained purpose-built cells equipped for torture. Kamal Gunaratne was also in charge post-war of internally displaced people – this was the illegal detention of 282,000 Tamil civilians who survived the war in Manik Farm and other sites. He also appears to have been involved in screening IDP’s for suspected ex combatants and putting them in the government’s “rehabilitation programme” which constituted wrongful detention according to the UN3. After the war as a diplomat, Gunaratne is alleged to have been involved in a murder in the Embassy in Brazil when posted there. -

The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

YS% ,xld m%cd;dka;s%l iudcjd§ ckrcfha .eiÜ m;%h The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka wxl 2"023 – 2017 cqks ui 09 jeks isl=rdod – 2017'06'09 No. 2,023 – FRIDAY, JUNE 09, 2017 (Published by Authority) PART I : SECTION (I) – GENERAL (Separate paging is given to each language of every Part in order that it may be fi led separately) PAGE PAGE Proclamations, &c., by the President … — Government Notifi cations … … 757 Appointments, &c., by the President … 758 Price Control Orders … … — Appointments, &c., by the Cabinet of Ministers … 774 Central Bank of Sri Lanka Notices… … — Accounts of the Government of Sri Lanka … — Appointments, &c., by the Public Service Commission — Revenue and Expenditure Returns… … — Appointments, &c., by the Judicial Service Commission — Miscellaneous Departmental Notices … 834 Other Appointments, &c. … … — Notice to Mariners … … — Appointments, &c., of Registrars … — “Excise Ordinance” Notices … … — Note.– Local Authorities Elections (Amendment) Bill was published as a supplement to the Part II of the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka of June 02, 2017. Laila Umma Deen Foundation (Incorporation) Bill was published as a supplement to the Part II of the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka of June 02, 2017. IMPORTANT NOTICE REGARDING ACCEPTANCE OF NOTICES FOR PUBLICATION IN THE WEEKLY “GAZETTE” ATTENTION is drawn to the Notifi cation appearing in the 1st week of every month, regarding the latest dates and times of acceptance of Notices for publication in the weekly Gazettes, at the end of every weekly Gazette of Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. -

Shavendra Silva Chief of Army Staff Sri Lanka

SHAVENDRA SILVA CHIEF OF ARMY STAFF SRI LANKA Dossier 29 January 2019 1 MAJOR GENERAL L. H. S. C. SILVA 58 Division Commander in 2009 “Our aim was not to gain ground but to have more kills.” Shavendra Silva1 1 Soldiers followed all humanitarian norms - Maj. Gen. Shavendra, Shanika Sriyananda, 27 Dec 2009, The Sunday Observer, http://archives.sundayobserver.lk/2001/pix/PrintPage.asp?REF=/2009/12/27/sec02.asp. Also cited on Silva’s Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/Major.General.shavendra.silva/posts/815949115103954 2 SUMMARY Shavendra Silva was arguably the most important frontline ground Commander in the 2008-9 War in Sri Lanka, in which a United Nations investigation found reasonable grounds to say international crimes were committed. He commanded a large number of troops throughout the offensive in the north of the island who were instrumental in the attacks on all the strategic towns and villages in 2009. He was also personally present at the surrenders at the end of the War, at which point hundreds of Tamils disappeared in Army custody and others, including women and children, were subjected to summary execution. Despite being one of the most notorious alleged war criminals and aligned to the Rajapaksa family, in January 2019 Silva was promoted to Chief of Staff of the Sri Lankan Army. This makes him number two in the Sri Lankan Army and next in line to become Commander. For those who survived the war he waged on them, this is a total affront. It also quashes any hope of Sri Lanka in the short term fulfilling its promise to deal with the past. -

Lessons from Sri Lanka's War – Indian Defence

Lessons from Sri Lanka's War By VK Shashikumar Issue: Vol 24.3 Jul-Sep 2009 | Date : 19 Nov , 2014 Terrorism has to be wiped out militarily and cannot be tackled politically. That’s the basic premise of the Rajapakse Model. Conduct of Operations This is how the Sri Lankan government described (through a Ministry of Defence Press Release) the war strategy of its defence forces on May 18, 2009 after the annihilation of the LTTE. “Security forces have marked a decisive victory in the humanitarian operations launched against terrorism by killing almost all senior cadres of the LTTE. The security forces commenced this humanitarian operation in August 2006 by liberating the Maavil Aru Anicut with the objective of wiping out terrorism from the country. An area of 15,000 square kilometres was controlled by the LTTE terrorists by 2006. Now the forces have completely liberated the entire territory of Sri Lanka from the LTTE terrorists. After liberating the Eastern Province from the clutches of terrorism on the 11th of July in 2007, the troops launched the Wanni humanitarian operation to liberate the innocent civilians from the terrorists in 2007.” “The operation was launched by three battle fronts. On March 2007, the 57th Division of the Army under the Security forces have command of Major General Jagath Dias commencing its marked a decisive operations from Vavuniya marched towards the North. victory in the They gained control of the Kilinochchi town on the 2nd of January this year, which was considered as the heartland humanitarian of the LTTE. In parallel to this, the 58th division, then Task operations launched Force One, commanded by Brigadier Shavendra Silva against terrorism by commenced its operations from the Silavathura area in killing almost all Mannar in the western coast of the island. -

The Men Now Patrolling Sri Lanka | ITJP - JDS

The Men Now Patrolling Sri Lanka | ITJP - JDS THE MEN NOW PATROLLING SRI LANKA Dossier MAY 2019 1 The Men Now Patrolling Sri Lanka | ITJP - JDS A JOINT REPORT WITH JOURNALISTS FOR DEMOCRACY IN SRI LANKA THE MEN NOW PATROLLING SRI LANKA On Easter Sunday 2019, a series of coordinated bomb blasts struck hotels and churches in Sri Lanka killing more than 250 people, including many tourists. The targets were churches in Colombo, Negombo and Batticaloa and five star hotels in the capital. The attacks are thought to have been suicide bombings carried out by a local Islamist group Lanka but Amaq News Agency, a propaganda outlet for the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), later claimed responsibility. Following the attacks there was considerable fear and panic about whether all the perpetrators had been apprehended and the possibility of further bombings. As a result security was stepped up considerably. The army is quoted by media sources as saying 10,000 troops were deployed in the wake of the tragic Easter Sunday bombings1. As in the war period, these troops enjoy extraordinary powers to detain any suspect. The re-imposition of the Emergency Regulations confer on the army and police sweeping powers of search and seizure, detention or arrest of any person without a warrant or court approval2. The Emergency Regulations are in addition to existing counter-terrorism legislation, overdue to be reformed to bring it in line with international standards3. Worryingly, there has already been a proposal for an immunity provision from prosecution for the Sri Lankan military and especially intelligence services4. -

Download Information from CALL’S Web Site

Handling Instructions for CALL Electronic Media and Paper Products Center for Army Lessons Learned (CALL) authorizes official use of this CALL product for operational and institutional purposes that contribute to the overall success of U.S., coalition, and allied efforts. The information contained in this product reflects the actions of units in the field and may not necessarily be approved U.S. Army policy or doctrine. This product is designed for official use by U.S., coalition, and allied personnel and cannot be released to the public without the expressed written consent of CALL. This product has been furnished with the expressed understanding that it will be used for official defense-related purposes only and that it will be afforded the same degree of protection that the U.S. affords information marked “U.S. UNCLASSIFIED, For Official Use Only [FOUO]” in accordance with U.S. Army Regulation (AR) 380-5, section 5-2. Official military and civil service/government personnel, to include all coalition and allied partners may paraphrase; quote; or use sentences, phrases, and paragraphs for integration into official products or research. However, integration of CALL “U.S. UNCLASSIFIED, For Official Use Only [FOUO]” information into official products or research renders them FOUO, and they must be maintained and controlled within official channels and cannot be released to the public without the expressed written consent of CALL. This product may be placed on protected UNCLASSIFIED intranets within military organizations or units, provided that access is restricted through user ID and password or other authentication means to ensure that only properly accredited military and government officials have access to these products. -

YS% ,Xld M%Cd;Dka;S%L Iudcjd§ Ckrcfha .Eiü M;%H the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

N. B. - (i) Part IV A of the Gazette No. 1,981 of 19.08.2016 was not published. (ii) The List of Jurors in Kurunegala and Kuliyapitiya Jurisdiction area in year 2016, have been published in Part VI of this Gazette in all Three Languages. YS% ,xld m%cd;dka;s%l iudcjd§ ckrcfha .eiÜ m;%h The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka wxl 1"982 – 2016 wf.daia;= ui 26 jeks isl=rdod – 2016'08'26 No. 1,982 – fRiDAy, AuGuSt 26, 2016 (Published by Authority) PART I : SECTION (I) – GENERAL (Separate paging is given to each language of every Part in order that it may be filed separately) PAGE PAGE Proclamations, &c., by the President … — Government Notifications … … 876 Appointments, &c., by the President … 866 Price Control Orders … … — Appointments, &c., by the Cabinet of Ministers … — Central Bank of Sri Lanka Notices… … — Accounts of the Government of Sri Lanka … — Appointments, &c., by the Public Service Commission — Revenue and Expenditure Returns… … — Appointments, &c., by the Judicial Service Commission — Miscellaneous Departmental Notices … 877 Other Appointments, &c. … … 868 Notice to Mariners … … — Appointments, &c., of Registrars … — “Excise Ordinance” Notices … … — Note.– Registration of Deaths (Temporary Provisions) (Amendment) Bill is published as a supplement to the Part II of the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka of June 10, 2016. IMportant NOTICE REGARDING Acceptance OF NOTICES FOR PUBlication IN THE WEEKLY “GAZETTE” AttENtiON is drawn to the Notification appearing in the 1st week of every month, regarding the latest dates and times of acceptance of Notices for publication in the weekly Gazettes, at the end of every weekly Gazette of Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. -

Restricted Restricted

RESTRICTED RESTRICTED RESTRICTED FOREWORD Throughout its illustrious history, the Sri Lanka Army has served the country in line with national interests. The glorious journey of the Army through the years, its utmost dedication and exceptional contributions made both during times of conflict and peace have inspired confidence amongst all citizens of Sri Lanka. The continuous commitment made by the Sri Lanka Army for nearly three decades to eradicate terrorism from the country made the Army victorious and professional in stature. At present, the evolving nature of security is more unpredictable and amorphous than ever before, which necessitates the Army to be vigilant to conduct and sustain diversified missions across all spheres. Hence, the Sri Lanka Army keeps pace with the modern advancements in order to seize, retain and exploit the opportunities to elevate the professionalism of the Army, and ensure national security. Moreover, the Sri Lanka Army, as guardians of the Nation, has to carry out a diverse array of tasks in multiple domains with a great sence of responsibility in order to provide necessary assistance to the citizenry whenever needed. In addition to performing its primary duties, the Army has to be a professional, modular and agile force to address the challenges of providing assistance for achieving the national goal of alleviating poverty from Sri Lanka, accelerating the development initiatives of the state, and providing humanitarian assistance for disaster mitigation. This Annual Report will undoubtedly guide the Sri Lanka Army to reflect on the past year as it works towards further enhancing capabilities of its personnel to accomplish the goals set for the year 2017. -

Island of Impunity?

International Crimes Evidence Project ICEP Sri Lanka . International Crimes Evidence Project ICEP Sri Lanka . International Crimes Evidence Project ICEP Sri Lanka . ISLAND OF IMPUNITY? Investigation into international crimes in the final stages of the Sri Lankan civil war International Crimes Evidence Projects ICEP group SRI LANKA . International Crimes Evidence Project ICEP Sri Lanka International Crimes Evidence Project I C E P Sri Lanka International Crimes Evidence Project ICEP Sri Lanka International Crimes Evidence Project ICEP Sri Lanka International Crimes Evidence Project ICEP Sri Lanka February 2014 International Crimes Evidence Project © Copyright Public Interest Advocacy Centre Ltd PIAC provides this report to you for the purpose of assisting in the process of deliberating on and discussing the need for accountability for alleged international crimes and related events that took place in the final stages of the Sri Lankan civil war, including through the UN Human Rights Council process. PIAC authorises you to use this report only for that purpose. Public Interest Advocacy Centre Ltd Level 7, 173-175 Phillip St Sydney NSW 2000 Australia Tel: +61 2 8898 6500 Fax: +61 2 8898 6555 Email: [email protected] www.piac.asn.au ABN: 77 002 773 524 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY i ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS x MAPS OF SRI LANKA xii 2 INTRODUCTION 1 A. International Crimes Evidence Project 1 B. Committee of Experts 1 C. Purpose of this report 2 D. Terms of reference 2 E. Methodology 3 3 BACKGROUND TO THE CONFLICT 5 4 PARTIES TO THE CONFLICT 7 5 LEGAL FRAMEWORK 8 A. The applicable rules of international law 8 B. -

The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka Wxl 2"120 – 2019 Wfm%A,A Ui 18 Jeks N%Yiam;Skaod – 2019'04'18 No

N. B.- Part iV (A) of the Gazette No. 2119 of 12.04.2019 was not published. YS% ,xld m%cd;dka;s%l iudcjd§ ckrcfha .eiÜ m;%h The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka wxl 2"120 – 2019 wfm%a,a ui 18 jeks n%yiam;skaod – 2019'04'18 No. 2,120 – thuRSDAy, APRiL 18, 2019 (Published by Authority) PART I : SECTION (I) – GENERAL (Separate paging is given to each language of every Part in order that it may be filed separately) PAGE PAGE Proclamations, &c., by the President … — Government Notifications … … — Appointments, &c., by the President … 642 Price Control Orders … … — Appointments, &c., by the Cabinet of Ministers … — Central Bank of Sri Lanka Notices… … — Appointments, &c., by the Public Service Commission — Accounts of the Government of Sri Lanka … — Revenue and Expenditure Returns… … — Appointments, &c., by the Judicial Service Commission — Miscellaneous Departmental Notices … 683 Other Appointments, &c. … … 679 Notice to Mariners … … — Appointments, &c., of Registrars … — “Excise Ordinance” Notices … … — IMportant NOTICE REGARDING Acceptance OF NOTICES FOR PUBlication IN THE WEEKLY “GAZETTE” AttENtiON is drawn to the Notification appearing in the 1st week of every month, regarding the latest dates and times of acceptance of Notices for publication in the weekly Gazettes, at the end of every weekly Gazette of Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. All notices to be published in the weekly Gazettes shall close at 12.00 noon of each Friday, two weeks before the date of publication. All Government Departments, Corporations, Boards, etc. are hereby advised that Notifications fixing closing dates and times of applications in respect of Post-Vacancies, Examinations, tender Notices and dates and times of Auction Sales, etc.