Normalising the Abnormal: the Militarisation of Mullaitivu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter Supporting Communities in Need

NEWSLETTER ICRC JULY-SEPTEMBER 2014 SUPPORTING COMMUNITIES IN NEED Economic security and water and sanitation for the vulnerable Dear Reader, they could reduce the immense economic This year, the ICRC started a Community Conflicts destroy livelihoods and hardships and poverty under which they Based Livelihood Support Programme infrastructure which provide water and and their families are living at present” (para (CBLSP) to support vulnerable communities sanitation to communities. Throughout 5.112). in the Mullaitivu and Kilinochchi districts the world, the ICRC strives to enable access to establish or consolidate an income to clean water and sanitation and ensure The ICRC’s response during the recovery generating activity. economic security for people affected by phase to those made vulnerable by the conflict so they can either restore or start a conflict was the piloting of a Micro Economic The ICRC’s economic security programmes livelihood. Initiatives (MEI) programme for women- are closely linked to its water and sanitation headed households, people with disabilities initiatives. In Sri Lanka today, the ICRC supports and extremely vulnerable households in vulnerable households and communities In Sri Lanka, the ICRC restores wells the Vavuniya district in 2011. The MEI is in the former conflict areas to become contaminated as a result of monsoonal a programme in which each beneficiary economically independent through flooding, and renovates and builds pipe identifies and designs the livelihood sustainable income generation activities and networks, overhead water tanks, and for which he or she needs assistance to provides them clean water and sanitation by toilets in rural communities for returnee implement, thereby employing a bottom- cleaning wells and repairing or constructing populations to have access to clean water up needs-based approach. -

YS% ,Xld M%Cd;Dka;S%L Iudcjd§ Ckrcfha .Eiü M;%H the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

YS% ,xld m%cd;dka;s%l iudcjd§ ckrcfha .eiÜ m;%h The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka wxl 1"991 – 2016 Tlaf;dan¾ ui 28 jeks isl=rdod – 2016'10'28 No. 1,991 – fRiDAy, OCtOBER 28, 2016 (Published by Authority) PART I : SECTION (I) – GENERAL (Separate paging is given to each language of every Part in order that it may be filed separately) PAGE PAGE Proclamations, &c., by the President … — Government Notifications … … 1204 Appointments, &c., by the President … 1128 Price Control Orders … … — Appointments, &c., by the Cabinet of Ministers … — Central Bank of Sri Lanka Notices… … — Accounts of the Government of Sri Lanka … — Appointments, &c., by the Public Service Commission — Revenue and Expenditure Returns… … — Appointments, &c., by the Judicial Service Commission — Miscellaneous Departmental Notices … 1206 Other Appointments, &c. … … 1192 Notice to Mariners … … — Appointments, &c., of Registrars … — “Excise Ordinance” Notices … … — Note.– (i) Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Bill was published as a supplement to the part ii of the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka of August 12, 2016. (ii) Nation Building tax (Amendment) Bill was published as a supplement to the part ii of the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka of August 19, 2016. (iii) Land (Restrictions on Alienation) (Amendment) Bill was published as a supplement to the part ii of the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka of September 02, 2016. IMportant NOTICE REGARDING Acceptance OF NOTICES FOR PUBlication IN THE WEEKLY “GAZETTE” AttENtiON is drawn to the Notification appearing in the 1st week of every month, regarding the latest dates and times of acceptance of Notices for publication in the weekly Gazettes, at the end of every weekly Gazette of Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. -

Integrated Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka Report

Integrated Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka A multi-agency approach coordinated by Central Environment Authority and Disaster Management Centre, Supported by United Nations Development Programme and United Nations Environment Programme Integrated Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka November 2014 A Multi-agency approach coordinated by the Central Environmental Authority (CEA) of the Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy and Disaster Management Centre (DMC) of the Ministry of Disaster Management, supported by United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Integrated Strategic Environment Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka ISBN number: 978-955-9012-55-9 First edition: November 2014 © Editors: Dr. Ananda Mallawatantri Prof. Buddhi Marambe Dr. Connor Skehan Published by: Central Environment Authority 104, Parisara Piyasa, Battaramulla Sri Lanka Disaster Management Centre No 2, Vidya Mawatha, Colombo 7 Sri Lanka Related publication: Map Atlas: ISEA-North ii Message from the Hon. Minister of Environment and Renewable Energy Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is a systematic decision support process, aiming to ensure that due consideration is given to environmental and other sustainability aspects during the development of plans, policies and programmes. SEA is widely used in many countries as an aid to strategic decision making. In May 2006, the Cabinet of Ministers approved a Cabinet of Memorandum -

Tides of Violence: Mapping the Sri Lankan Conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre

Tides of violence: mapping the Sri Lankan conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre The Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) is an independent, non-profit legal centre based in Sydney. Established in 1982, PIAC tackles barriers to justice and fairness experienced by people who are vulnerable or facing disadvantage. We ensure basic rights are enjoyed across the community through legal assistance and strategic litigation, public policy development, communication and training. 2nd edition May 2019 Contact: Public Interest Advocacy Centre Level 5, 175 Liverpool St Sydney NSW 2000 Website: www.piac.asn.au Public Interest Advocacy Centre @PIACnews The Public Interest Advocacy Centre office is located on the land of the Gadigal of the Eora Nation. TIDES OF VIOLENCE: MAPPING THE SRI LANKAN CONFLICT FROM 1983 TO 2009 03 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 09 Background to CMAP .............................................................................................................................................09 Report overview .......................................................................................................................................................09 Key violation patterns in each time period ......................................................................................................09 24 July 1983 – 28 July 1987 .................................................................................................................................10 -

The Impacts of Small Arms Availability and Misuse in Sri Lanka

In the Shadow of a Cease-fire: The Impacts of Small Arms Availability and Misuse in Sri Lanka by Chris Smith October 2003 A publication of the Small Arms Survey Chris Smith The Small Arms Survey The Small Arms Survey is an independent research project located at the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva, Switzerland. It is also linked to the Graduate Institute’s Programme for Strategic and International Security Studies. Established in 1999, the project is supported by the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, and by contributions from the Governments of Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. It collaborates with research institutes and non-governmental organizations in many countries including Brazil, Canada, Georgia, Germany, India, Israel, Jordan, Norway, the Russian Federation, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Thailand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The Small Arms Survey occasional paper series presents new and substantial research findings by project staff and commissioned researchers on data, methodological, and conceptual issues related to small arms, or detailed country and regional case studies. The series is published periodically and is available in hard copy and on the project’s web site. Small Arms Survey Phone: + 41 22 908 5777 Graduate Institute of International Studies Fax: + 41 22 732 2738 47 Avenue Blanc Email: [email protected] 1202 Geneva Web site: http://www.smallarmssurvey.org Switzerland ii Occasional Papers No. 1 Re-Armament in Sierra Leone: One Year After the Lomé Peace Agreement, by Eric Berman, December 2000 No. 2 Removing Small Arms from Society: A Review of Weapons Collection and Destruction Programmes, by Sami Faltas, Glenn McDonald, and Camilla Waszink, July 2001 No. -

Collective Trauma in the Vanni- a Qualitative Inquiry Into the Mental Health of the Internally Displaced Due to the Civil War in Sri Lanka Daya Somasundaram

Somasundaram International Journal of Mental Health Systems 2010, 4:22 http://www.ijmhs.com/content/4/1/22 RESEARCH Open Access Collective trauma in the Vanni- a qualitative inquiry into the mental health of the internally displaced due to the civil war in Sri Lanka Daya Somasundaram Abstract Background: From January to May, 2009, a population of 300,000 in the Vanni, northern Sri Lanka underwent multiple displacements, deaths, injuries, deprivation of water, food, medical care and other basic needs caught between the shelling and bombings of the state forces and the LTTE which forcefully recruited men, women and children to fight on the frontlines and held the rest hostage. This study explores the long term psychosocial and mental health consequences of exposure to massive, existential trauma. Methods: This paper is a qualitative inquiry into the psychosocial situation of the Vanni displaced and their ethnography using narratives and observations obtained through participant observation; in depth interviews; key informant, family and extended family interviews; and focus groups using a prescribed, semi structured open ended questionnaire. Results: The narratives, drawings, letters and poems as well as data from observations, key informant interviews, extended family and focus group discussions show considerable impact at the family and community. The family and community relationships, networks, processes and structures are destroyed. There develops collective symptoms of despair, passivity, silence, loss of values and ethical mores, amotivation, dependency on external assistance, but also resilience and post-traumatic growth. Conclusions: Considering the severity of family and community level adverse effects and implication for resettlement, rehabilitation, and development programmes; interventions for healing of memories, psychosocial regeneration of the family and community structures and processes are essential. -

Projected Economic Growth in North & East Regions Will Be 13 Per Cent

Published in Canada by The Times of Sri Lanka Vol.9 JUNE 2011 Projected economic growth in North & East regions will be 13 per cent over five years The economy of Sri Lanka’s once war-torn Northern and Eastern provinces are set to grow by around 13 percent per annum from 2011 onwards for the next five years, according to the Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL). CBSL Governor Ajith Nivard Cabraal (inset) made these remarks in delivering the 60th Anniversary Oration of the CBSL a fortnight ago, on the topic of ‘Promoting financial inclusiveness – The experience of the past two years’. “There is a clear drive towards holistic development in the North and East to ensure that people sustain their economic achievements and translate them into a way of life. We expect that the range of investments made in these provinces will result in a growth rate of around 13 percent per annum in these provinces, from 2011 onwards for the next five years,” Cabraal said. According to the Governor, it has been encouraging to see that the Northern Province (NP) had recorded the highest nominal growth rate of 14% in 2009 ahead of all other Provinces although on a low base. The contribution to the country’s GDP by the NP increased to 3.3% in 2009 from 2.8% in 2006. The Eastern Province on the other hand recorded the second-highest nominal growth rate of all provinces, at 14% in 2009 while its contribution to the country’s GDP increased to 5.8% in 2009 from 4.9% in 2006. -

Children & Armed Conflict in Sri Lanka

CHILDREN & ARMED CONFLICT IN SRI LANKA Displaced Tamil girl at Mannar Reception Centre, 1995 ©Howard Davies / Exile Images A discussion document prepared for UNICEF Regional Office South Asia Jason Hart Ph.D REFUGEE STUDIES CENTRE, OXFORD UNIVERSITY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report is based upon material collected in Sri Lanka and the United Kingdom. In the gathering, consideration and analysis of this material I have enjoyed the support and assistance of many people. I should here like to offer my thanks to them. Firstly, I am indebted to Reiko Nishijima at UNICEF-ROSA who has been responsible for the overall project of which this report is part. I should like to thank Reiko and her assistants, Damodar Adhikari and Tek Chhetri, for their warm support. At the Sri Lanka Country Office of UNICEF I was fortunate to be welcomed and greatly assisted by staff members throughout the organisation. My particular thanks go to the following people in the Colombo office: Jean-Luc Bories, Avril Vandersay, Maureen Bocks, U.L Jaufer, Irene Fraser, and the country representative, Colin Glennie. With the assistance of UNICEF’s drivers and logistics staff I was able to visit all five of the field offices where my work was facilitated most thoroughly by Monica Martin (Batticaloa), Gabriella Elroy (Trincomalee), I.A. Hameed, Bashir Thani & N. Sutharman (Vavuniya), Penny Brune (Mallavi), A. Sriskantharajan & Kalyani Ganeshmoorthy (Jaffna). My gratitude also goes to the numerous other individuals and organisations who helped during my seven week stay in Sri Lanka. Lack of space prevents me from mentioning all except a handful: Gunnar Andersen and Rajaram Subbian (Save the Children, Norway), Pauline Taylor-McKeown (SC UK), Alan Vernon and numerous colleagues (UNHCR), Markus Mayer, (IMCAP), Jenny Knox (Thiruptiya), Sunimal Fernando (INASIA), Jeevan Thiagarajah and Lakmali Dasanayake (CHA), various staff at ZOA, Ananda Galappatti (War-Trauma & Psychosocial Support Programme) Father Saveri (CPA) and Father Damien (Wholistic Health Centre). -

2013 Titled “Sri Lanka As a Hub in Asia: the Way Forward”

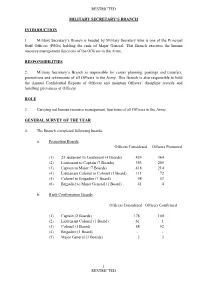

RESTRICTED MILITARY SECRETARY’S BRANCH INTRODUCTION 1. Military Secretary‟s Branch is headed by Military Secretary who is one of the Principal Staff Officers (PSOs) holding the rank of Major General. This Branch executes the human resource management functions of the Officers in the Army. RESPONSIBILITIES 2. Military Secretary‟s Branch is responsible for career planning, postings and transfers, promotions and retirements of all Officers in the Army. This Branch is also responsible to hold the Annual Confidential Reports of Officers and maintain Officers‟ discipline records and handling grievances of Officers. ROLE 3. Carrying out human resource management functions of all Officers in the Army. GENERAL SURVEY OF THE YEAR 4. The Branch completed following boards: a. Promotion Boards. Officers Considered Officers Promoted (1) 2/Lieutenant to Lieutenant (4 Boards) 424 364 (2) Lieutenant to Captain (7 Boards) 393 205 (3) Captain to Major (7 Boards) 418 214 (4) Lieutenant Colonel to Colonel (1 Board) 111 72 (5) Colonel to Brigadier (1 Board) 98 57 (6) Brigadier to Major General (1 Board) 41 4 b. Rank Confirmation Boards. Officers Considered Officers Confirmed (1) Captain (2 Boards) 178 100 (2) Lieutenant Colonel (1 Board) 61 1 (3) Colonel (1 Board) 58 52 (4) Brigadier (1 Board) - - (5) Major General (3 Boards) 3 3 1 RESTRICTED RESTRICTED c. Selection of Officers for Selected Majors List (1 Board): Officers Considered Officers Selected Major 129 60 5. Further to above, this Branch published the Officers Seniority list for 2014. ACHIEVEMENTS 6. Overall co-ordination of the Second Army Symposium 2013 titled “Sri Lanka as a Hub in Asia: the Way Forward”. -

Ancient Water Management and Governance in the Dry Zone of Sri Lanka Until Abandonment, and the Influence of Colonial Politics During Reclamation

water Article Ancient Water Management and Governance in the Dry Zone of Sri Lanka Until Abandonment, and the Influence of Colonial Politics during Reclamation Nuwan Abeywardana * , Wiebke Bebermeier * and Brigitta Schütt Department of Earth Sciences, Physical Geography, Freie Universität Berlin, Malteserstr. 74-100, 12249 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (N.A.), [email protected] (W.B.) Received: 30 October 2018; Accepted: 21 November 2018; Published: 27 November 2018 Abstract: The dry-zone water-harvesting and management system in Sri Lanka is one of the oldest historically recorded systems in the world. A substantial number of ancient sources mention the management and governance structure of this system suggesting it was initiated in the 4th century BCE (Before Common Era) and abandoned in the middle of the 13th century CE (Common Era). In the 19th century CE, it was reused under the British colonial government. This research aims to identify the ancient water management and governance structure in the dry zone of Sri Lanka through a systematic analysis of ancient sources. Furthermore, colonial politics and interventions during reclamation have been critically analyzed. Information was captured from 222 text passages containing 560 different records. 201 of these text passages were captured from lithic inscriptions and 21 text passages originate from the chronicles. The spatial and temporal distribution of the records and the qualitative information they contain reflect the evolution of the water management and governance systems in Sri Lanka. Vast multitudes of small tanks were developed and managed by the local communities. Due to the sustainable management structure set up within society, the small tank systems have remained intact for more than two millennia. -

12 Manogaran.Pdf

Ethnic Conflict and Reconciliation in Sri Lanka National Capilal District Boundarl3S * Province Boundaries Q 10 20 30 010;1)304050 Sri Lanka • Ethnic Conflict and Reconciliation in Sri Lanka CHELVADURAIMANOGARAN MW~1 UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS • HONOLULU - © 1987 University ofHawaii Press All Rights Reserved Manufactured in the United States ofAmerica Library ofCongress Cataloging-in-Publication-Data Manogaran, Chelvadurai, 1935- Ethnic conflict and reconciliation in Sri Lanka. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Sri Lanka-Politics and government. 2. Sri Lanka -Ethnic relations. 3. Tamils-Sri Lanka-Politics and government. I. Title. DS489.8.M36 1987 954.9'303 87-16247 ISBN 0-8248-1116-X • The prosperity ofa nation does not descend from the sky. Nor does it emerge from its own accord from the earth. It depends upon the conduct ofthe people that constitute the nation. We must recognize that the country does not mean just the lifeless soil around us. The country consists ofa conglomeration ofpeople and it is what they make ofit. To rectify the world and put it on proper path, we have to first rec tify ourselves and our conduct.... At the present time, when we see all over the country confusion, fear and anxiety, each one in every home must con ., tribute his share ofcool, calm love to suppress the anger and fury. No governmental authority can sup press it as effectively and as quickly as you can by love and brotherliness. SATHYA SAl BABA - • Contents List ofTables IX List ofFigures Xl Preface X111 Introduction 1 CHAPTER I Sinhalese-Tamil -

Third Spot Report

THIRD SPOT REPORT How the International Community’s Passivity Has Enabled Further Mass Atrocities in Sri Lanka: the Case of Ongoing Illegal Detention, Torture, and Sexual Violence 7 March 2018 * * * MAP – Third Spot Report Page 1 of 34 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. In October 2015, the Government of Sri Lanka (GSL) committed to a broad transitional-justice agenda pursuant to UN Human Rights Council (HRC) Resolution 30/1. The measures included accountability mechanisms to address some of the worst crimes of the 21st Century. Since then, the GSL has proceeded in bad faith, reneged on its international commitments, and violated its legal obligations to victims. To make matters worse, Sri Lankan security forces have continued to commit serious crimes—including arbitrary deprivations of liberty, torture, and sexual violence—with impunity. Seemingly, the failure of the international community to hold Sri Lanka to account for past crimes has encouraged the continuation of violations. 2. Since the filing of the MAP’s last report in November 2017, the GSL has made zero progress on its transitional justice agenda, despite damning assessments by UN Special Rapporteurs and human rights organizations. Calls for a time- bound benchmarked action plan for implementation of Resolution 30/1 have fallen on deaf ears. The US and EU appear to be more interested in nurturing bilateral relationships with the GSL in reaction to China’s increasing influence. And President Sirisena has maintained his position that any special court set up to investigate war crimes will not include foreign participation. Observers lament that ‘Sri Lanka has shown how it’s possible to hoodwink the international community, always asking for space and time’.