Arkadian Landscapes”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Mycenaean Arkadia: Space and Place(S) of an Inland and Mountainous Region

Early Mycenaean Arkadia: Space and Place(s) of an Inland and Mountainous Region Eleni Salavoura1 Abstract: The concept of space is an abstract and sometimes a conventional term, but places – where people dwell, (inter)act and gain experiences – contribute decisively to the formation of the main characteristics and the identity of its residents. Arkadia, in the heart of the Peloponnese, is a landlocked country with small valleys and basins surrounded by high mountains, which, according to the ancient literature, offered to its inhabitants a hard and laborious life. Its rough terrain made Arkadia always a less attractive area for archaeological investigation. However, due to its position in the centre of the Peloponnese, Arkadia is an inevitable passage for anyone moving along or across the peninsula. The long life of small and medium-sized agrarian communities undoubtedly owes more to their foundation at crossroads connecting the inland with the Peloponnesian coast, than to their potential for economic growth based on the resources of the land. However, sites such as Analipsis, on its east-southeastern borders, the cemetery at Palaiokastro and the ash altar on Mount Lykaion, both in the southwest part of Arkadia, indicate that the area had a Bronze Age past, and raise many new questions. In this paper, I discuss the role of Arkadia in early Mycenaean times based on settlement patterns and excavation data, and I investigate the relation of these inland communities with high-ranking central places. In other words, this is an attempt to set place(s) into space, supporting the idea that the central region of the Peloponnese was a separated, but not isolated part of it, comprising regions that are also diversified among themselves. -

Bakke-Alisoy.Pdf

Papers and Monographs from the Norwegian Institute at Athens, Volume 5 Local and Global Perspectives on Mobility in the Eastern Mediterranean Edited by Ole Christian Aslaksen the Norwegian Institute at Athens 2016 © 2016 The Norwegian Institute at Athens Typeset by Rich Potter. ISBN: 978-960-85145-5-3 ISSN: 2459-3230 Communication and Trade at Tegea in the Bronze Age Hege Agathe Bakke-Alisøy Communication is a central part of any discussion of the Aegean Bronze Age and the development of the Minoan and Mycenaean civilisations. Movement and communication is always present in human society. The archaeological material from the Tegean Mountain plain indicates the importance of inland communication on the Peloponnese during the Bronze Age. I here look at the settlement structure at the Tegean plain in the Bronze Age, and its relation to possible routes of communication and trade. By discussing changes in settlement pattern, land use, and sacred space my aim is to trace possible changes in the local and regional communication networks in this area. During the EH communication and trade networks at Tegea seems primarily to have had a local focus, with some connection to the more developed trade nodes in the Gulf of Argos. A strong Minoan influenced trade network is also observed in Tegea from the MN and early LH with Analipsis and its strong connection to Laconia. The abandonment of Analipsis correlates with changes in the communication patterns due to a strong Mycenaean culture in the Argolid by the end of LH. The changes observed in the communication network suggest that Tegea, with its central location on the Peloponnese, could be seen as an interjection for all inland communication. -

Athens Guide

ATHENS GUIDE Made by Dorling Kindersley 27. May 2010 PERSONAL GUIDES POWERED BY traveldk.com 1 Top 10 Athens guide Top 10 Acropolis The temples on the “Sacred Rock” of Athens are considered the most important monuments in the Western world, for they have exerted more influence on our architecture than anything since. The great marble masterpieces were constructed during the late 5th-century BC reign of Perikles, the Golden Age of Athens. Most were temples built to honour Athena, the city’s patron goddess. Still breathtaking for their proportion and scale, both human and majestic, the temples were adorned with magnificent, dramatic sculptures of the gods. Herodes Atticus Theatre Top 10 Sights 9 A much later addition, built in 161 by its namesake. Acropolis Rock In summer it hosts the Athens Festival (see Festivals 1 As the highest part of the city, the rock is an ideal and Events). place for refuge, religion and royalty. The Acropolis Rock has been used continuously for these purposes since Dionysus Theatre Neolithic times. 10 This mosaic-tiled theatre was the site of Classical Greece’s drama competitions, where the tragedies and Propylaia comedies by the great playwrights (Aeschylus, 2 At the top of the rock, you are greeted by the Sophocles, Euripides) were first performed. The theatre Propylaia, the grand entrance through which all visitors seated 15,000, and you can still see engraved front-row passed to reach the summit temples. marble seats, reserved for priests of Dionysus. Temple of Athena Nike (“Victory”) 3 There has been a temple to a goddess of victory at New Acropolis Museum this location since prehistoric times, as it protects and stands over the part of the rock most vulnerable to The Glass Floor enemy attack. -

The Geotectonic Evolution of Olympus Mt and Its

Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, vol. XLVII 2013 Δελτίο της Ελληνικής Γεωλογικής Εταιρίας, τομ. XLVII , 2013 th ου Proceedings of the 13 International Congress, Chania, Sept. Πρακτικά 13 Διεθνούς Συνεδρίου, Χανιά, Σεπτ. 2013 2013 THE GEOTECTONIC EVOLUTION OF OLYMPUS MT. AND ITS MYTHOLOGICAL ANALOGUE Mariolakos I.D.1 and Manoutsoglou E.2 1 National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Faculty of Geology and Geoenvironment, Department of Dynamic, Tectonic & Applied Geology, Panepistimioupoli, Zografou, GR 157 84, Athens, Greece, [email protected] 2 Technical University of Crete, Department of Mineral Resources Engineering, Research Unit of Geology, Chania, 73100, Greece, [email protected] Abstract Mt Olympus is the highest mountain of Greece (2918 m.) and one of the most impor- tant and well known locations of the modern world. This is related to its great cul- tural significance, since the ancient Greeks considered this mountain as the habitat of their Gods, ever since Zeus became the dominant figure of the ancient Greek re- ligion and consequently the protagonist of the cultural regime. Before the genera- tion of Zeus, Olympus was inhabited by the generation of Cronus. In this paper we shall refer to a lesser known mythological reference which, in our opinion, presents similarities to the geotectonic evolution of the wider area of Olympus. According to Apollodorus and other great authors, the God Poseidon and Iphimedia had twin sons, the Aloades, namely Otus and Ephialtes, who showed a tendency to gigantism. When they reached the age of nine, they were about 16 m. tall and 4.5 m. wide. -

VENETIANS and OTTOMANS in the SOUTHEAST PELOPONNESE (15Th-18Th Century)

VENETIANS AND OTTOMANS IN THE SOUTHEAST PELOPONNESE (15th-18th century) Evangelia Balta* The study gives an insight into the historical and economic geography of the Southeast Peloponnese frorm the mid- fifteenth century until the morrow of the second Ottoma ill conquest in 1715. It necessarily covers also the period of Venetialll rule, whiciL was the intermezzo between the first and second perio.ds of Ottoman rule. By utilizing the data of an Ottoman archivrul material, I try to compose, as far as possible, the picture ())f that part of the Peloponnese occupied by Mount Pamon, which begins to t he south of the District of Mantineia, extends througlhout the D:istrict of Kynouria (in the Prefecture of Arcadia), includes the east poart of the District of Lacedaimon and the entire District of Epidavros Limira . Or. Evangelia Balta, Director of Studies (Institute for N1eohellenic Resea rch/ National Hellenic Research Foundation). Venetians and Oltomans in the Southeast Peloponnese 169 (in the Prefecture of Laconia), and ends at Cape Malea. 1 The Ottoman archival material available to me for this particular area comprises certain unpublished fiscal registers of the Morea, deposited in the Ba§bakal1lIk Osmal1lI Al"§ivi in Istanbul, which I have gathered together over the last decade, in the course of collecting testimonies on the Ottoman Peloponnese. The material r have gleaned is very fragmentary in relation to what exists and I therefore wish to stress that th e information presented here for the first time does not derive from an exhaustive archival study for the area. Nonetheless, despite the fact that the material at my disposal covers the region neither spatially nor temporarily, in regard to the protracted period of Ottoman rule, J have decided to discuss it here for two reasons: I. -

Geographical Index

Geographical Index Achaia: 15, 21, 34, 47, 68, 134, 146, 148, 160, 162–167, Antheia: 43, 86, 149, 289, 308–309, 413, 572, 575–577, 172, 304, 385, 388–390, 395–398, 402, 404, 414, 602 541–542, 583, 599, 602–603, 608 – Ellinika: 296 Agoulinitsa Lagoon: 133–134, 136 – Epia: 413 Agriapidies: see Chalandritsa – Kastroulia: 43, 242, 296–299, 301, 572, 575–576 Aidonia: 509–510, 583, 594 – Makria Rachi: 289, 308 – Chamber Tomb 7: 509–510 – Thouria: 242 Aigina: 14–16, 21–23, 39, 41–43, 50, 112, 120, 144, 259, Antikythera: 368 285, 408, 428, 437, 442, 463, 487, 517–536, 539, Aphidna: 297, 434 541, 543, 551, 554, 556–557, 559, 561–562, 569, “Aphrodite Erykina”, Sanctuary: see Ayios Petros 572, 575–576, 584 Apollo Epikourios, Temple: see Vasses – Kolonna: 14, 23, 41–44, 298, 301, 428, 430, 435, Apollo Maleatas, Sanctuary: see Epidauros 437, 444, 487, 517–536, 551, 553, 555, 557, 559, Apulia: see Italy 569, 575, 584 Araxos: 133 – Kiln: 23, 519, 527–528, 536, 555 Archanes: see Crete – Large Building Complex: 23, 517, 519–528, 536 Arene: see Kato Samikon – Shaft Grave: 43, 298, 301, 428, 430, 435, 437, Argassi-Neratzoules: see Zakynthos 444, 519–520, 572 Argive Gulf: see Gulf of Argos Aigion: 113, 388, 390–391, 395–396, 541–542, 583 Argive Heraion: see Prosymna Aitolia: 148, 164, 303, 386, 388–389, 541 Argive Plain: 22, 423, 470, 479, 484–488, 490–491, 604 Aitolo-Akarnania: 164–165, 168, 172, 584, 599, 603 Argolid: 15, 17, 21–24, 42–43, 45, 47, 107, 113, 117, Akkadian States: 41 121, 141, 144, 190, 215, 237, 240–242, 244–245, Akona: see Koukounara 251–252, -

1 Introduction: Taking Testimony, Making Archives

Notes 1 Introduction: Taking Testimony, Making Archives Notes to Pages 2–5 1. K. Gavroglou, “Sweet Memories from Tzimbali.” To Vima, August 29, 1999. 2. I am indebted for the use of the term personal archive to a panel organized by colleagues Laura Kunreuther and Carole McGranahan at the American Anthropological Association Meetings in San Francisco in November 2000, entitled “Personal Archives: Collections, Selves, Histories.” On the historian’s “personal archives,” see LaCapra (1985b). 3. On the history and theory of collecting and collections, see, for instance, Benjamin (1955), Stewart (1993), Crane (2000), Chow (2001). 4. The interdisciplinary literature on memory is voluminous, including studies on the “art of memory” from antiquity to modernity (Yates 1966; Matsuda 1996); monuments, public commemoration, and “lieux de mémoire” (Nora 1989; Young 1993; Gillis 1994; Sider and Smith 1997); photography, film, and other kinds of “screen memories” (Kuhn 1995; Hirsch 1997; Sturken 1997; Davis 2000; Strassler 2003); public history and national her- itage (Wright 1985; Hewison 1987; Samuel 1994); and trauma, testimony, and the “sci- ences of memory,” such as psychoanalysis (Langer 1991; Felman and Laub 1992; Caruth 1995, 1996; Hacking 1995; Antze and Lambek 1996); as well as many theoretical analy- ses, review articles, and comparative cultural studies (Connerton 1989; Hutton 1993; Olick and Robbins 1998; Bal, Crewe, and Spitzer 1999; Ben-Amos and Weissberg 1999; Stoler and Strassler 2000). 5. For commentaries on the “memory boom” as a “postmodern” phenomenon, see Fischer (1986), Huyssen (1995). James Faubion has argued that anthropological interest in history and memory might be ascribed to astute “participant observation” of a world in which the past has become the “privileged ground of individual and collective identity, entitlements, of la condition humaine,” but charges nonetheless that “anthropologists have been more likely to reflect this transformation than reflect upon it” (1993b: 44). -

Commission Implementing Decision of 22 August 2018 on the Publication

28.8.2018 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 302/13 COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING DECISION of 22 August 2018 on the publication in the Official Journal of the European Union of an application for amendment of a specification for a name in the wine sector referred to in Article 105 of Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council (‘Μαντινεία’ (Mantinia) (PDO)) (2018/C 302/10) THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 establishing a common organisation of the markets in agricultural products and repealing Council Regulations (EEC) No 922/72, (EEC) No 234/79, (EC) No 1037/2001 and (EC) No 1234/2007 (1), and in particular Article 97(3) thereof, Whereas: (1) Greece has sent an application for amendment of the specification for the name ‘Μαντινεία’ (Mantinia) in accordance with Article 105 of Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013. (2) The Commission has examined the application and concluded that the conditions laid down in Articles 93 to 96, Article 97(1), and Articles 100, 101 and 102 of Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 have been met. (3) In order to allow for the presentation of statements of opposition in accordance with Article 98 of Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013, the application for amendment of the specification for the name ‘Μαντινεία’ (Mantinia) should be published in the Official Journal of the European Union, HAS DECIDED AS FOLLOWS: Sole Article The application for amendment of the specification for the name ‘Μαντινεία’ (Mantinia) (PDO), in accordance with Article 105 of Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013, is contained in the Annex to this Decision. -

Greek Motorway Concessions

GENERAL SECRETARIAT FOR CONCESSIONS GREEK MOTORWAY CONCESSIONS SEPTEMBER 2011 Preface This Report presents in summary the problems that were encountered during the implementation of the five Greek Motorway Concessions Projects that are under construction, the actions taken by the General Secretariat for Concessions of the Hellenic Ministry of Infrastructure, Transport and Networks (MITN) and the progress of negotiations with the Concessionaires and the lending Banks to this day. The technical and financial analysis for every project is reported and a solution to the problems is investigated. The basic elements of the New Toll Policy which should be followed after the completion of the negotiations are also presented. This report aims to assist in improving the understanding and coordination of the jointly responsible Ministries of Infrastructure, Transport and Networks and Finance and their Consultants in the next phase of negotiations with the Concessionaires and Lending Banks. Responsibility for the contents of this report lies with the undersigned. The views and proposals included in this report by no means bind the Greek State. Contributors to the compilation of this report:: Stefania Trezou, Dr. Civil Engineer NTUA, Technical Consultant in the General Secretariat for Concessions. Kleopatra Petroutsatou, Dr. Civil Engineer NTUA, Administrator in the General Secretariat for Concessions. Georgios P. Smyrnioudis, Partner, Ernst & Young, who had the responsibility of the financial calculations, and his associates. Additional participants in the Working Groups during negotiations: Antonios Markezinis, Legal Advisor for Concessions of Ministry of Infrastructure, Transport and Networks. Dimitrios Anagnostopoulos, Civil Engineer NTUA, Technical Consultant in the General Secretariat for Concessions. The responsible Directors of the MITN and their teams. -

Print Sheet Remote1

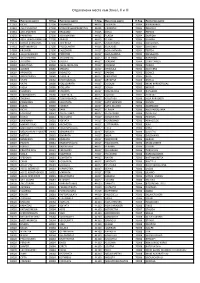

Отдалечени места към Зона I, II и III П.Код Населено място П.Код Населено място П.Код Населено място П.Код Населено място 11361 KICELI 27100 KERAMIDIA 44015 LAGKADA 70004 KSEROKABOS 12351 AGIA VARVARA 27100 MONI FRAGKOPIDIMATOS 44015 LIKORRAXI 70004 PERVOLA 13561 AGII ANARGIRI 27100 TRAGANO 44015 OKSIA 70004 PEFKOS 13672 PARNITHA 27200 AGIA MARINA 44015 PLAGIA 70004 SKAFIDIA 13679 AGIA TRIADA PARNITHAS 27200 ANALICI 44015 PLIKATI 70004 STAFRIA 13679 KSENIA PARNITHAS 27200 ASTEREIKA 44015 PIRSOGIANNI 70004 SIKOLOGOS 14451 METAMORFOSI 27200 PALEOLANTHI 44015 XIONADES 70004 SINDONIA 14568 KRIONERI 27200 PALEOXORI 44017 AGIA VARVARA 70004 TERTSA 15342 AGIA PARASKEFI 27200 PERISTERI 44017 AGIA MARINA 70004 FAFLAGKOS 18010 AGIA MARINA 27300 AGIA MAFRA 44017 VEDERIKOS 70004 XONDROS 18010 AGKISTRI 27300 KALIVIA 44017 VERENIKI 70004 CARI FORADA 18010 EGINITISSA 28080 AGIOS NIKOLAOS 44017 VROSINA 70005 AVDOU 18010 ALONES 28080 GRIZATA 44017 VRISOULA 70005 ANO KERA 18010 APONISOS 28080 DIGALETO 44017 GARDIKI 70005 GONIES 18010 APOSPORIDES 28080 ZERVATA 44017 GKRIBOVO 70005 KERA 18010 VATHI 28080 KARAVOMILOS 44017 GRANITSA 70005 KRASIO 18010 VATHI 28080 KOULOURATA 44017 DIXOUNI 70005 MONI KARDIOTISSAS 18010 VIGLA 28080 POULATA 44017 DOVLA 70005 MOXOS 18010 VLAXIDES 28080 STAVERIS 44017 DOMOLESSA 70005 POTAMIES 18010 GIANNAKIDES 28080 TZANEKATA 44017 ZALOGO 70005 SFENDILI 18010 THERMA 28080 TSAKARISIANOS 44017 KALLITHEA 70006 AGIA PARASKEFI 18010 KANAKIDES 28080 XALIOTATA 44017 KATO VERENIKI 70006 AGNOS 18010 KLIMA 28080 XARAKTI 44017 KATO ZALOGO -

Church, Society, and the Sacred in Early Christian Greece

CHURCH, SOCIETY, AND THE SACRED IN EARLY CHRISTIAN GREECE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By William R. Caraher, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved By Professor Timothy E. Gregory, Adviser Professor James Morganstern Professor Barbara Hanawalt _____________________ Adviser Professor Nathan Rosenstein Department of History ABSTRACT This dissertation proposes a social analysis of the Early Christian basilicas (4th-6th century) of Southern and Central Greece, predominantly those in the Late Roman province of Achaia. After an introduction which places the dissertation in the broader context of the study of Late Antique Greece, the second chapter argues that church construction played an important role in the process of religions change in Late Antiquity. The third chapter examines Christian ritual, architecture, and cosmology to show that churches in Greece depended upon and reacted to existing phenomena that served to promote hierarchy and shape power structures in Late Roman society. Chapter four emphasizes social messages communicated through the motifs present in the numerous mosaic pavements which commonly adorned Early Christian buildings in Greece. The final chapter demonstrates that the epigraphy likewise presented massages that communicated social expectations drawn from both an elite and Christian discourse. Moreover they provide valuable information for the individuals who participated in the processes of church construction. After a brief conclusion, two catalogues present bibliographic citations for the inscriptions and architecture referred to in the text. The primary goal of this dissertation is to integrate the study of ritual, architecture, and social history and to demonstrate how Early Christian architecture played an important role in affecting social change during Late Antiquity. -

The Fortifications of Arkadian Poleis in the Classical and Hellenistic Periods

THE FORTIFICATIONS OF ARKADIAN POLEIS IN THE CLASSICAL AND HELLENISTIC PERIODS by Matthew Peter Maher BA, The University of Western Ontario, 2002 BA, The University of Western Ontario, 2005 MA, The University of British Columbia, 2007 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Classics) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) March 2012 © Matthew Peter Maher, 2012 Abstract This study comprises a comprehensive and detailed account of the historical development of Greek military architecture and defensive planning specifically in Arkadia in the Classical and Hellenistic periods. It aims to resolve several problems, not least of all, to fill the large gap in our knowledge of both Arkadian fortifications and the archaeology record on the individual site level. After establishing that the Arkadian settlements in question were indeed poleis, and reviewing all previous scholarship on the sites, the fortification circuit of each polis is explored through the local history, the geographical/topographical setting, the architectural components of the fortifications themselves, and finally, the overall defensive planning inherent in their construction. Based an understanding of all of these factors, including historical probability, a chronology of construction for each site is provided. The synthesis made possible by the data gathered from the published literature and collected during the field reconnaissance of every site, has confirmed a number of interesting and noteworthy regionally specific patterns. Related to chronology, it is significant that there is no evidence for fortified poleis in Arkadia during the Archaic period, and when the poleis were eventually fortified in the Classical period, the fact that most appeared in the early fourth century BCE, strategically distributed in limited geographic areas, suggests that the larger defensive concerns of the Arkadian League were a factor.