Technologyandthe Growth of Textile Manufacturein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Needham Market | IP6 8AL Guide Price: £725,000

Burnley House | 37 High Street | Needham Market | IP6 8AL Guide Price: £725,000 Specialist marketing for | Barns | Cottages | Period Properties | Executive Homes | Town Houses | Village Homes To find out more or arrange a viewing please contact 01449 722003 or visit www.townandvillageproperties.co.uk Burnley House, 37 High Street, Needham Market, Suffolk, IP6 8AL “An impressive five bedroom period townhouse, situated in the heart of this popular market town boasting superbly presented & spacious accommodation along with a beautiful south facing walled garden offering plenty of parking.” Description Burnley House is a magnificent Georgian townhouse situated in the heart of this popular vibrant Suffolk market town. The accommodation comprises: entrance hall, drawing room, sitting room, dining room, kitchen/breakfast room, cellar, utility room, shower room, galleried landing, four bedrooms, en-suite to master bedroom, family bathroom, cloakroom, linen room and second floor attic/bedroom five. Fronting the high street, this impressive and substantial family home has been beautifully and sympathically restored by the current owers. The property displays many features of a property of this period, these include high ceilings, sash windows, cornicing, ceiling roses, impressive entrance hall and many attractive and a good local primary school. Alder Drawing Room Approx 14’8 x 13’8 fireplaces. Carr Farm offers fresh farm food for sale (4.48m x 4.15m) and a restaurant. Feature bay window to front elevation, Further benefits include a luxury fitted two radiators, cornicing, picture rail, bespoke kitchen with granite work Needham Market also has good transport attractive open fireplace with marble surfaces, large utility room with shower links with bus and train services into surround and hearth, storage cupboard room off, useful cellar, en-suite to master Stowmarket and Ipswich, where there are and dado rail. -

THE NEEDHAM MARKET NEWSLETTER PUBLISHED by NEEDHAM MARKET TOWN COUNCIL May 2016 - No 478 and Distributed Throughout Needham Market Free of Charge

THE NEEDHAM MARKET NEWSLETTER PUBLISHED BY NEEDHAM MARKET TOWN COUNCIL May 2016 - No 478 and Distributed Throughout Needham Market Free of Charge Needham Market Raft Race 2016 ‘Movie Madness’ Sunday 12th June See Page 7 for more details www.needhammarkettc.co.uk TOWN COUNCIL Needham Market Town Council OFFICE TOWN CLERK: ASSISTANT TOWN CLERK: Town Council Office, Kevin Hunter Kelaine Spurdens Community Centre, School Street, LIST OF TOWN COUNCILLORS: TELEPHONE: Needham Market IP6 8BB BE ANNIS OBE Grinstead House, Grinstead Hill, NM IP6 8EY 01449 720531 Telephone: (07927 007895) 01449 722246. D CAMPBELL ‘Chain House’ 1 High Street, NM, IP6 8AL 01449 720952 An answerphone is in operation when the office R CAMPBELL The Acorns, Hill House Lane, NM, IP6 8EA 01449 720729 is unmanned. TS CARTER Danescroft, Ipswich Road, NM, IP6 8EG 01449 401325 The office is open to the RP DARNELL 27 Pinecroft Way, NM, IP6 8HB 07990 583162 public Mondays and JE LEA MA Town Mayor/Chair of Council Thursdays 10am to 109 Jubilee Crescent, NM IP6 8AT 01449 721544 12noon. I MASON 114 Quinton Road, NM IP6 8TH 01449 721162 E.mail: MG NORRIS 20 Stowmarket Road, NM, IP6 8DS 01449 720871 clerk@needhammarkettc. KMN OAKES, 89 Stowmarket Road, NM, IP6 8ED 07702 339971 f9.co.uk S PHILLIPS 46 Crowley Road IP6 8BJ 01449 721710 Web: D SPURLING 36 Drift Court, NM, IP6 8SZ 01449 401443 www.needhammarkettc. M SPURLING 36 Drift Court, NM, IP6 8SZ 01449 401443 co.uk X STANSFIELD Deputy Town Mayor/Deputy Chair of Council Hope Cottage, 7 Stowmarket Road IP6 8DR 07538 058304 Town Council meetings are held on the first and AL WARD MBE 22 Chalkeith Road, NM, IP6 8HA 01449 720422 third Wednesdays of each month at 7:25 p.m. -

Gypsies and Travellers Short Stay Stopping Sites: Call for Sites

Gypsies and Travellers Short Stay Stopping Sites: Call for Sites 23 September 2015 – 16 November 2015 Suffolk‘s Public Sector working together www.suffolk.gov.uk/shortstay 1 Foreword Cllr Sarah Stamp, Russell Williams, Cabinet Member for Communities Gypsy and Traveller Lead for Suffolk County Council Suffolk Chief Executives Group We - as political leaders and chief executives of public services across Suffolk - have a We are looking to put in place three Short Stay Stopping Sites across the county. We believe responsibility to ensure the needs of all of the people that live in our county are met. these sites will save the taxpayer money, help meet the needs of the Gypsy and Traveller community and reduce unauthorised encampments. The sites will not be used as a While the needs of many of our residents are easily, and readily, identifiable, we must also permanent base. ensure that the needs of the Gypsy and Traveller community are met too. This Call for Sites is the start of a process which will be open, thorough and carefully managed Suffolk’s county, district and borough councils, Suffolk Constabulary and Suffolk’s health to ensure the needs of both the settled community and the Gypsy and Traveller community services, have pledged their commitment to this. One of the first steps is to identify where are considered before any decisions are taken. Our commitment is to provide the right sites, in best to locate a number of Short Stay Stopping Sites. At present, Suffolk does not currently the right locations, with strict suitability criteria that any potential site will have to meet. -

Suffolk Rail Prospectus Cromer Sheringham West Runton Roughton Road

Suffolk Rail Prospectus Cromer Sheringham West Runton Roughton Road Gunton East Anglia Passenger Rail Service North Walsham Worstead King’s Lynn Hoveton & Wroxham Norwich Salhouse Watlington Brundall Lingwood Acle Wymondham Downham Market Brundall Buckenham Peterborough Spooner Row Gardens Great Littleport Yarmouth March Cantley Lakenheath Thetford Attleborough Reedham Berney Arms Whittlesea Eccles Road Manea Shippea Brandon Harling Haddiscoe Road Hill Diss Somerleyton Ely Regional Oulton Broad North Waterbeach Bury St. Oulton Broad South Edmunds Lowestoft Chesterton (working name) Kennett Thurston Elmswell Beccles Newmarket Dullingham Stowmarket Brampton Cambridge Halesworth Shelford Darsham Whittlesford Parkway Saxmundham Great Chesterford Needham Market Wickham Market Audley End Melton Newport Great Eastern Westerfield Woodbridge Elsenham Stansted Airport Derby Road Stansted Ipswich Express Stansted Mountfitchet Felixstowe Sudbury Bishop’s Stortford Hertford Trimley East Sawbridgeworth Bures Wrabness Dovercourt Manningtree Ware Harlow Mill Mistley Harwich Harwich Chappel and International Town St. Margarets Harlow Town Wakes Colne Roydon Colchester Walton-on-the-Naze Rye House Braintree Broxbourne Hythe Great Frinton-on-Sea Wivenhoe West Cheshunt Braintree Freeport Colchester Bentley Weeley Anglia Town Waltham Cross Cressing Alresford Kirby Marks Tey Thorpe-le-Soken Enfield Lock Cross White Notley Brimsdown Kelvedon Edmonton Clacton-on-Sea Green Ponders End Witham Angel Road Chelmsford Hatfield Peverel Northumberland Park Southminster -

Conservation Area Appraisal

CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Needham Market NW © Crown copyright All rights reserved Mid Suffolk D C Licence no 100017810 2010 INTRODUCTION The conservation area in Needham Market was designated in 1970 by East Suffolk County Council, and inherited by Mid Suffolk District Council at its inception in 1974. It was last appraised and extended by Mid Suffolk District Council in 2000. The Council has a duty to review its conservation area designations from time to time, and this appraisal examines Needham Market under a number of different headings as set out in English Heritage’s ‘Guidance on Conservation Area Appraisals’ (2006). As such it is a straightforward appraisal of Needham Market’s built environment in conservation terms. This document is neither prescriptive nor overly descriptive, but more a demonstration of ‘quality of place’, sufficient for the briefing of the Planning Officer when assessing proposed works in the area. The Town Sign photographs and maps are thus intended to contribute as much as the text itself. As the English Heritage guidelines point out, the appraisal is to be read as a general overview, rather than as a comprehensive listing, and the omission of any particular building, feature or space does not imply that it is of no interest in conservation terms. Text, photographs and map overlays by Patrick Taylor, Conservation Architect, Mid Suffolk District Council 2011. View South-east down High Street Needham Market SE © Crown copyright All rights reserved Mid Suffolk D C Licence no 100017810 2010 TOPOGRAPHICAL FRAMEWORK Needham Market is situated in central Suffolk, eight miles north-west of Ipswich between 20m and 40m above OD. -

Needham Market Football Club Address ‘Bloomfields’ Quinton Road, Needham Market, Ipswich

2 WELCOME NOTES This evening we welcome the officials, staff, players and supporters of Debenham LC to ‘Bloomfields for this Thurlow Nunn First Division North fixture. We would also like to extend this welcome to today’s match officials. It is almost a year since the two teams have played against each other and this evening Needham Reserves will look to continue their winning ways after Saturday’s 3-2 victory over second place Diss Town. Callum Page weighed in with another brace with Ben Harris scoring the other. The match report can be seen on page 12 Debenham LC on the other hand lost at home to our local rivals AFC Sudbury Reserves 4-2 on Saturday. It was their third defeat in four league game, so no doubt they will be wanting to change their fortunes. I’m sure it will be an exciting game and know you will all get behind the team and help them towards victory….. Enjoy the game and your visit to Bloomfields…..Lastly have a safe journey home afterwards….. Previous Season’s Meetings: 17/10/18 Needham Market Res 1-0 Debenham LC 24/8/18 Debenham LC 2-1 Needham Market Res 7/4/18 Debenham LC 1-1 Needham Market Res 20/3/18 Needham Market Res 0-3 Debenham LC 25/2/17 Debenham LC 3-0 Needham Market Res 27/9/16 Needham Market Res 1-1 Debenham LC Other Thurlow Nunn First Division North Fixtures Ipswich Wanderers vs Framlingham Town @ SEH Sports Centre Norwich CBS vs Mulbarton Wanderers @ The FDC 3 Needham Market Football Club Address ‘Bloomfields’ Quinton Road, Needham Market, Ipswich. -

THE NEEDHAM MARKET NEWSLETTER PUBLISHED by NEEDHAM MARKET TOWN COUNCIL October 2016 - No 483 and Distributed Throughout Needham Market Free of Charge

THE NEEDHAM MARKET NEWSLETTER PUBLISHED BY NEEDHAM MARKET TOWN COUNCIL October 2016 - No 483 and Distributed Throughout Needham Market Free of Charge Needham Market Fireworks Display and Torchlight Procession at Bloomfields Football Ground Saturday 5th November See Page 17 for more details www.needhammarkettc.co.uk TOWN COUNCIL Needham Market Town Council OFFICE TOWN CLERK: ASSISTANT TOWN CLERK: Town Council Office, Kevin Hunter Kelaine Spurdens Community Centre, School Street, LIST OF TOWN COUNCILLORS: TELEPHONE: Needham Market IP6 8BB BE ANNIS OBE Grinstead House, Grinstead Hill, NM IP6 8EY 01449 720531 Telephone: (07927 007895) 01449 722246. D CAMPBELL ‘Chain House’ 1 High Street, NM, IP6 8AL 01449 720952 An answerphone is in operation when the office R CAMPBELL Deputy Town Mayor/Deputy Chair of Council is unmanned. The Acorns, Hill House Lane, NM, IP6 8EA 01449 720729 The office is open to the TS CARTER Danescroft, Ipswich Road, NM, IP6 8EG 01449 401325 public Mondays and RP DARNELL 27 Pinecroft Way, NM, IP6 8HB 07990 583162 Thursdays 10am to JE LEA MA 109 Jubilee Crescent, NM IP6 8AT 01449 721544 12noon. I MASON 114 Quinton Road, NM IP6 8TH 01449 721162 E.mail: A MORRIS 8 Chainhouse Road, IP6 8EP 01449 720161 clerk@needhammarkettc. MG NORRIS 20 Stowmarket Road, NM, IP6 8DS 01449 720871 f9.co.uk KMN OAKES, 89 Stowmarket Road, NM, IP6 8ED 07702 339971 Web: S PHILLIPS 46 Crowley Road IP6 8BJ 01449 721710 www.needhammarkettc. D SPURLING 36 Drift Court, NM, IP6 8SZ 01449 401443 co.uk M SPURLING 36 Drift Court, NM, IP6 8SZ 01449 401443 Town Council meetings X STANSFIELD Town Mayor/Chair of Council are held on the first and Hope Cottage, 7 Stowmarket Road IP6 8DR 07538 058304 third Wednesdays of each month at 7:25 p.m. -

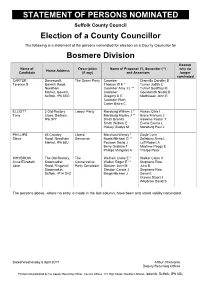

Statement of Persons Nominated

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED Suffolk County Council Election of a County Councillor The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a County Councillor for Bosmere Division Reason Name of Description Name of Proposer (*), Seconder (**) why no Home Address Candidate (if any) and Assentors longer nominated CARTER Danescroft, The Green Party Coomber Granville Dorothy B Terence S Ipswich Road, Thomas W F * Turner Judith C Needham Coomber Amy J L ** Turner Geoffrey M Market, Ipswich, Coomber Gouldsmith Nicola B Suffolk, IP6 8EG Gregory D E Matthissen John E Coomber Ruth Carter Bistra C ELLIOTT 3 Old Rectory Labour Party Marsburg William J * Hiskey Clive I Tony Close, Barham, Marsburg Hayley J ** Brace Frances J IP6 0PY Smith Brenda Hawkins Kester T Smith William E Evans Emma L Hiskey Gladys M Marsburg Paul J PHILLIPS 46 Crowley Liberal Marchant Wendy * Gayle Lynn Steve Road, Needham Democrat Norris Michael G ** Salisbury Anna L Market, IP6 8BJ Poulson David J Luff Robert A Berry Graham T Mayhew Peggy E Phillips Margaret A Thorpe Peter WHYBROW The Old Rectory, The Welham Claire E * Walker Claire V Anne Elizabeth Stowmarket Conservative Walker Roger E ** Stephens-Row Jane Road, Ringshall, Party Candidate Stratton John M Julia B Stowmarket, Stratton Carole J Stephens-Row Suffolk, IP14 2HZ Brega Michael J David E Groves Stuart J Whybrow David S The persons above, where no entry is made in the last column, have been and stand validly nominated. Dated Wednesday 5 April 2017 Arthur Charvonia Deputy Returning Officer Printed -

Needham Market - Stowmarket 88

Ipswich - Needham Market - Stowmarket 88 Monday to Friday (Except Bank Holidays) Operator FNS FNS FNS FNS FNS FNS FNS FNS FNS FNS FNS FNS FNS FNS FNS Service Restrictions NSch Sch Ipswich, Old Cattle Market Bus Station (D) 0635 0745 0845 0915 then 15 45 until 1345 1415 1415 1445 1530 1615 1645 1715 1745 Ipswich, Tower Ramparts Bus Station (FF) 0638 0748 0848 0918at 18 48 1348 1418 1418 1448 1533 1618 1648 1718 1748 Westbourne, Norbridge Social Club (o/s) 0646 0756 0856 0926these 26 56 1356 1426 1426 1456 1541 1628 1658 1728 1758 Claydon, The Greyhound (adj) 0656 0806 0906 0936mins 36 06 1406 1436 1436 1506 1551 1638 1708 1738 1808 Great Blakenham, Chequers (adj) 0659 0809 0909 0939past 39 09 1409 1439 1439 1509 1554 1641 1711 1741 1811 Needham Market, The Swan (adj) 0706 0816 0916 0946each 46 16 1416 1446 1446 1516 1601 1650 1720 1750 1820 Combs Ford, Cracknells (o/s) 0715 0825 0925 0955hour 55 25 1425 1455 1455 1525 1610 1700 1730 1800 1830 Stowmarket, Argos Store (o/s) arr 0720 0830 0930 1000 00 30 1430 1500 1500 1530 1615 1705 1735 1805 1835 Stowmarket, Argos Store (o/s) dep 1502 1805 1835 Stowmarket, Recreation Ground (opp) 1503 1806 1836 Stowmarket, Kipling Way (adj) 1509 1812 1842 Stowmarket, Newbolt Close (opp) 1511 1814 1844 Stowmarket, Beech Terrace (opp) 1514 1817 1847 Saturday Operator FNS FNS FNS FNS FNS FNS FNS Ipswich, Old Cattle Market Bus Station (D) 0745 0815 then 15 45 until 1645 1715 1745 Ipswich, Tower Ramparts Bus Station (FF) 0748 0818at 18 48 1648 1718 1748 Westbourne, Norbridge Social Club (o/s) 0756 0826these -

THE NEEDHAM MARKET NEWSLETTER PUBLISHED by NEEDHAM MARKET TOWN COUNCIL June 2019 - No 512 and Distributed Throughout Needham Market Free of Charge

THE NEEDHAM MARKET NEWSLETTER PUBLISHED BY NEEDHAM MARKET TOWN COUNCIL June 2019 - No 512 and Distributed Throughout Needham Market Free of Charge 275 YEARS OF CRICKET IN NEEDHAM MARKET SEE PAGE 17 www.needhammarkettc.co.uk Needham Market Town Council Newsletter Copy: All copy for the newsletter must TOWN CLERK: DEPUTY TOWN CLERK: TOWN COUNCIL be emailed to [email protected] Kevin Hunter Kelaine Spurdens OFFICE in Microsoft Word format Town Council Office, LIST OF TOWN COUNCILLORS: TELEPHONE: Copy deadline is always the 8th School Street of the month prior to publication BE Annis (01449) 720531 Needham Market and deadline for the July 2019 Suffolk, IP6 8BB Issue is 8th June 2019 please. N Andrews (01449) 721302 C Campbell (01449) 720952 The office is open to the public All Advertising queries should be Mondays and Thursdays: referred to Kelaine at the Town RP Darnell 07790 583162 Council Office on: (01449) 722246 10 am to 12 noon. JE Lea MA (01449) 721544 or email as above. I Mason (01449) 721162 Telephone: (01449) 722246 NEEDHAM MG Norris (01449) 720871 An answerphone is in operation MARKET LIBRARY when the office Is unmanned. P Potter (01449) 723948 School Street, S Phillips (01449) 721710 E.mail: Needham Market (Town Mayor / Chair of Council) [email protected] IP6 8BB Tel: (01449) 720780 D Campbell (01449) 720952 Website: (Deputy Town Mayor / Deputy Chair of Council) Opening Hours www.needhammarkettc.co.uk M Ost Monday Closed Town Council Meetings: D Spurling (01449) 401443 Tuesday 10am – 1pm & These are held on the first and 2pm – 5pm M Spurling (01449) 401443 third Wednesdays of each month Wednesday 2pm – 7pm X Stansfield 07538 058304 at 7:25 p.m. -

1. Parish: Needham Market (Former Hamlet of Barking)

1. Parish: Needham Market (former hamlet of Barking) Meaning: a) Poor homestead/village with a market b) Enclosure of Haydda’s people with market (Ekwall) 2. Hundred: BOSMERE (- 1327), BOSEMERE AND CLAYDON Deanery: Bosmere Union: Bosmere and Claydon RDC/UDC: Bosmere and Claydon R.D. (1901-1934), Gipping R.D. (1934-1974), Mid-Suffolk D.C. (1974 -) Other administrative details: Separate from Barking and acquiring civil parish status (1901), separated ecclesiastically (1907) Civil boundary change (1907), gains part of Creeting St. Mary Bosmere and Claydon Petty Sessional Division Stowmarket County Court District 3. Area: 451 acres (1912) 4. Soils: Mixed: a. Deep weel drained loam and sandy soils, locally flinty, in places over gravel, slight risk water erosion b. Slowly permeable calcareous/non calcareous clay soils, slight risk water erosion c. Stoneless clay soils mostly overlying peat by river, variably affected by groundwater, risk of localised flooding 5. Types of farming: 1500–1640 Thirsk: Wood-pasture region, mainly pasture, meadow engaged in rearing and dairying with some pig-keeping, horse breeding and poultry. Crops mainly barley with some wheat, rye, oats, peas, vetches, hops and occasionally hemp. Also has similarities with sheep-corn region where sheep are main fertilising agent, bred for fattening, barley main cash crop 1818 Marshall: Wide variations of crop and management techniques including summer fallow in 1 preparation for corn and rotation of turnip, barley, clover, wheat on lighter lands 1937 Main crops: Urbanised area 6. Enclosure: 7. Settlement: 1958 River Gipping forms natural boundary to NE. Railway runs parallel to the river from NW – SE Small compact town development spaced along line of Stowmarket to Ipswich road, to west of railway. -

Needham Market | Suffolk | IP6 8DG Guide Price: £220,000

102 High Street | Needham Market | Suffolk | IP6 8DG Guide Price: £220,000 Specialist marketing for | Barns | Cottages | Period Properties | Executive Homes | Town Houses | Village Homes To find out more or arrange a viewing please contact 01449 722003 or visit www.townandvillageproperties.co.uk 102 High Street, Needham Market, Suffolk, IP6 8DG “A wonderful opportunity to acquire this charming two bedroom characterful home offering an abundance of period features with the benefit of being close to local amenities.” Description An appealing two bedroom character townhouse situated in the heart of Needham Market’s High Street and close to everyday amenities. The accommodation comprises: sitting room, dining room, kitchen, landing, two bedrooms and bathroom. This delightful period home offers an abundance of charm and character to include exposed timbers, exposed brickwork, focal fireplaces, open studwork and some boarded flooring to the first floor. Further benefits include a delightful bespoke fitted kitchen, gas fired central heating, newly installed gas boiler and is superbly presented throughout. Outside to the rear is an enclosed low maintenance courtyard garden which can be accessed via the kitchen and offers a pedestrian gate to King William Street. About the Area Needham Market is a desirable small town situated in the heart of Mid Suffolk between the towns of Bury St Edmunds and Ipswich. There are a range of everyday amenities and individual shops including butcher, baker, tea shops/cafes, public houses, take-away restaurants, a post office and a Co-op supermarket. There is also a library, community centre, dentist and a good local primary school. Alder Carr Farm offers fresh farm food for sale and a restaurant.