Distribution and Abundance of Giant Fruit Bat (Pteropus Giganteus)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Preliminary Study of Viral Metagenomics of French Bat Species in Contact with Humans: Identification of New Mammalian Viruses

A preliminary study of viral metagenomics of French bat species in contact with humans: identification of new mammalian viruses. Laurent Dacheux, Minerva Cervantes-Gonzalez, Ghislaine Guigon, Jean-Michel Thiberge, Mathias Vandenbogaert, Corinne Maufrais, Valérie Caro, Hervé Bourhy To cite this version: Laurent Dacheux, Minerva Cervantes-Gonzalez, Ghislaine Guigon, Jean-Michel Thiberge, Mathias Vandenbogaert, et al.. A preliminary study of viral metagenomics of French bat species in contact with humans: identification of new mammalian viruses.. PLoS ONE, Public Library of Science, 2014, 9 (1), pp.e87194. 10.1371/journal.pone.0087194.s006. pasteur-01430485 HAL Id: pasteur-01430485 https://hal-pasteur.archives-ouvertes.fr/pasteur-01430485 Submitted on 9 Jan 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License A Preliminary Study of Viral Metagenomics of French Bat Species in Contact with Humans: Identification of New Mammalian Viruses Laurent Dacheux1*, Minerva Cervantes-Gonzalez1, -

Viral Diversity Among Different Bat Species That Share a Common Habitatᰔ Eric F

JOURNAL OF VIROLOGY, Dec. 2010, p. 13004–13018 Vol. 84, No. 24 0022-538X/10/$12.00 doi:10.1128/JVI.01255-10 Copyright © 2010, American Society for Microbiology. All Rights Reserved. Metagenomic Analysis of the Viromes of Three North American Bat Species: Viral Diversity among Different Bat Species That Share a Common Habitatᰔ Eric F. Donaldson,1†* Aimee N. Haskew,2 J. Edward Gates,2† Jeremy Huynh,1 Clea J. Moore,3 and Matthew B. Frieman4† Department of Epidemiology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 275991; University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, Appalachian Laboratory, Frostburg, Maryland 215322; Department of Biological Sciences, Oakwood University, Huntsville, Alabama 358963; and Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Maryland at Baltimore, Baltimore, Maryland 212014 Received 11 June 2010/Accepted 24 September 2010 Effective prediction of future viral zoonoses requires an in-depth understanding of the heterologous viral population in key animal species that will likely serve as reservoir hosts or intermediates during the next viral epidemic. The importance of bats as natural hosts for several important viral zoonoses, including Ebola, Marburg, Nipah, Hendra, and rabies viruses and severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus (SARS-CoV), has been established; however, the large viral population diversity (virome) of bats has been partially deter- mined for only a few of the ϳ1,200 bat species. To assess the virome of North American bats, we collected fecal, oral, urine, and tissue samples from individual bats captured at an abandoned railroad tunnel in Maryland that is cohabitated by 7 to 10 different bat species. Here, we present preliminary characterization of the virome of three common North American bat species, including big brown bats (Eptesicus fuscus), tricolored bats (Perimyotis subflavus), and little brown myotis (Myotis lucifugus). -

Village and Town Directory, Puruliya, Part XII-A , Series-26, West Bengal

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES -26 WEST BENGAL DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART XII-A VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY PURULIYA DISTRICT DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS WEST BENGAL Price Rs. 30.00 PUBLISHED BY THE CONTROLLER GOVERNMENT PRINTING, WEST BENGAL AND PRINTED BY SARASWATY PRESS LTD. 11 B.T. ROAD, CALCUTTA -700056 CONTENTS Page No. 1. Foreword i-ii 2. Preface iii-iv 3. Acknowledgements v-vi 4. Important Statistics vii-viii 5. Analytical note and Analysis of Data ix-xxxiii Part A - Village and Town Directory 6. Section I - Village Directory Note explaining the Codes used in the Village Directory 3 (1) Hura C.D. Block 4-9 (a) Village Directory (2) Punch a C.D. Block 10-15 (a) Village Directory (3) Manbazar - I C.D. Block 16 - 29 (a) Village Directory (4) Manbazar -II C.D. Block 30- 41 (a) Village Directory (5) Raghunathpur - I C.D. Block 42-45 (a) Village Directory (6) Raghunathpur - II C.D. Block 46 - 51 (a) Village Directory (7) Bagmundi C.D. Block 52- 59 (a) Village Directory (a) Arsha C.D. Block 60-65 (a) Village Directory (9) Bundwan C.D. Block 66-73 (a) Village Directory (10) Jhalda -I C.D. Block 74 - 81 (a) Village Directory (11) Jhalda -II C.D. Block 82-89 (a) Village Directory (12) Neturia C.D. Block 90-95 (a) Village Directory (13) Kashipur C.O. Block 96 -107 (a) Village Directory (14) Santuri C.D. Block 108-115 (a) Village Directory (15) Para C.O. Block 116 -121 (a) Village Directory Page No. (16) Purulia -I C.D. -

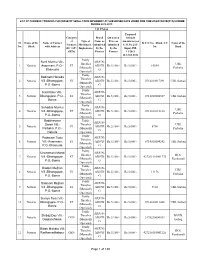

Ota Final List 1St Phase

LIST OF FARMERS TOWARDS PURCHASE OF SMALL FARM IMPLEMENT AT SUBSIDISED RATE UNDER ONE TIME ASSISTANCE(OTA)SCHEME DURING 2012-2013 1st Phase Proposed Category Brand Quotation Subsidy of Type of Name as Price as Amount as per Sl. Name of the Name of Farmer K.C.C.No. / Bank A/C Name of the Farmers Machinary / submitted submitted G.O.No.233- No. Block with Address No. Bank (SC / ST / Implements by the by the Input-9M- GEN) Farmer Farmer 11/2013 dt.12.02.2013 Paddy Sunil Murmu Vill.- ARJUN- Thresher UBI, 1 Neturia Asanmani, P.O.- ST AR07D Rs.5,100/- Rs.5,000/- 10054 (Manually Parbelia Bhamuria G Operated) Paddy Bodinath Hansda ARJUN- Thresher 2 Neturia Vill.-Dhangajore, ST AR07D Rs.5,100/- Rs.5,000/- 0714010017091 UBI, Sarbari (Manually P.O.-Bonra G Operated) Paddy Kati Kisku Vill.- ARJUN- Thresher 3 Neturia Dhangajore, P.O.- ST AR07D Rs.5,100/- Rs.5,000/- 0714010104517 UBI, Sarbari (Manually Bonra G Operated) Paddy Sahadeb Murmu ARJUN- Thresher UBI, 4 Neturia Vill.-Dhangajore, ST AR07D Rs.5,100/- Rs.5,000/- 0712010115100 (Manually Parbelia P.O.-Bonra G Operated) Buddheswar Paddy ARJUN- Soren Vill.- Thresher UBI, 5 Neturia ST AR07D Rs.5,100/- Rs.5,000/- 8708 Parbelia, P.O.- (Manually Parbelia G Neturia Operated) Paddy Patamani Tudu ARJUN- Thresher 6 Neturia Vill.-Asanmani, ST AR07D Rs.5,100/- Rs.5,000/- 0714010104242 UBI, Sarbari (Manually P.O.-Bhamuria G Operated) Paddy Chandmani Mandi ARJUN- Thresher BOI, 7 Neturia Vill.-Dhangajore, ST AR07D Rs.5,100/- Rs.5,000/- 427201110001776 (Manually Ramkanali P.O.-Bonra G Operated) Paddy Badani Mejhan -

E2767 V. 2 Public Disclosure Authorized ACCELERATED DEVELOPMENT of MINOR IRRIGATION (A.D.M.I) PROJECT in WEST BENGAL

E2767 v. 2 Public Disclosure Authorized ACCELERATED DEVELOPMENT OF MINOR IRRIGATION (A.D.M.I) PROJECT IN WEST BENGAL ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Public Disclosure Authorized ANNEXURE (Part II) November 2010 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Annexure - I - Map of West Bengal showing Environmental Features Annexure – II - Sample Blocks Annexure – III - Map of West Bengal Soils Annexure – IV - Ground Water Availability in Pilot Districts Annexure – V - Ground Water Availability in non-pilot districts Annexure – VI - Arsenic Contamination Maps of Districts Annexure – VII - Details of Wetlands more than 10 ha Annexure – VIII - Environmental Codes of Practice Annexure – IX - Terms of Reference for Limited EA Annexure – X - Environmental Survey Report of Sample Blocks Annexure – XI - Stakeholder Consultation Annexure – XII - Primary & Secondary Water Quality Data Annexure – XIII - Primary & Secondary Soil Quality Data Annexure – XIV - EMP Master Table ii Annexure II Sample Blocks for Environmental Assessment Agro- Hydrogeological No. of climatic Soil group District Block Status of the Block Samples zone Hill Zone Acid soils/sandy Jalpaiguri Mal Piedmont zone 1 loam Terai Acid soils/sandy Darjeeling Phansidewa Piedmont zone 1 Teesta loam Flood plain Acid soils/sandy Jalpaiguri Dhupguri Recent to sub-recent 1 loam alluvium Acid soils/sandy Coochbehar Tufangunge II Recent to sub-recent 1 loam alluvium Acid soils/sandy Coochbehar Sitai Recent to subrecent 1 loam alluvium Vindhyan Alluvial/sandy Dakshin Gangarampur( Older alluvium -

A Review of Chiropterological Studies and a Distributional List of the Bat Fauna of India

Rec. zool. Surv. India: Vol. 118(3)/ 242-280, 2018 ISSN (Online) : (Applied for) DOI: 10.26515/rzsi/v118/i3/2018/121056 ISSN (Print) : 0375-1511 A review of Chiropterological studies and a distributional list of the Bat Fauna of India Uttam Saikia* Zoological Survey of India, Risa Colony, Shillong – 793014, Meghalaya, India; [email protected] Abstract A historical review of studies on various aspects of the bat fauna of India is presented. Based on published information and study of museum specimens, an upto date checklist of the bat fauna of India including 127 species in 40 genera is being provided. Additionaly, new distribution localities for Indian bat species recorded after Bates and Harrison, 1997 is also provided. Since the systematic status of many species occurring in the country is unclear, it is proposed that an integrative taxonomic approach may be employed to accurately quantify the bat diversity of India. Keywords: Chiroptera, Checklist, Distribution, India, Review Introduction smallest one being Craseonycteris thonglongyai weighing about 2g and a wingspan of 12-13cm, while the largest Chiroptera, commonly known as bats is among the belong to the genus Pteropus weighing up to 1.5kg and a 29 extant mammalian Orders (Wilson and Reeder, wing span over 2m (Arita and Fenton, 1997). 2005) and is a remarkable group from evolutionary and Bats are nocturnal and usually spend the daylight hours zoogeographic point of view. Chiroptera represent one roosting in caves, rock crevices, foliages or various man- of the most speciose and ubiquitous orders of mammals made structures. Some bats are solitary while others are (Eick et al., 2005). -

West Bengal 2.Xlsx

NAME OF THE REPORTING NAME OF THE NAME OF THE HOSPITAL/ICTC UNIT POSTAL ADDRESS OF UNIT CONTACT NO. UNIT DISTRICTS COUNSELLOR (1) NO. SL.NO ICTC ANC UNIT, BARASAT DH, BANAMALIPUR, BARASAT, 1 BARASAT DH 24 PARGANAS (N) SOMA BASU DUTTA 9474570260 033‐25842209 KOL‐124 ICTC UNIT, BARASAT DH, BANAMALIPUR, BARASAT, KOL‐ 2 BARASAT DH 24 PARGANAS (N) PRIYANKA DUTTA 9883277034 033‐25842300 124 ICTC UNIT, DR. J.R.DHAR SD HOSPITAL, BONGAON, 3 BONGAON SDH 24 PARGANAS (N) UPENDRA KHUJUR 9933113431 03215‐240027 743235 4 BASIRHAT SDH ICTC UNIT, BASIRHAT SDH, 24 PGS (N) 24 PARGANAS (N) SANGITA PANDA 9830666322 ICTC UNIT, BHATPARA, PO‐JAGADDAL, 24 PGS (N), 5 BHATPARA SGH 24 PARGANAS (N) DEBJANI GUHA ROY 9836869683 25024541 743125 ICTC UNIT, NAIHATI SGH, 7NO, BIJOYNAGAR, PO+PS‐ 6 NAIHATISGH 24 PARGANAS (N) SAMBHUNATH BHOWMIK 9874649373 2502‐4561 NAIHATI, 743145 ICTC UNIT, ASHOKENAGAR SGH, KACHUA MORE, ASHOKE 7 ASHOKENAGAR SGH * 24 PARGANAS (N) KRISHNA DUTTA 9883177933 03216222230 NAGAR, 24PGS(N), 743222 8 HABRA SGH * ICTC HABRA SGH, HABRA, 24PGS (N), 743263 24 PARGANAS (N) ATASHI CHAKRABORTY 9831446909 03216‐238790 ANAMIKA SINGHA ROY, 9432925673, 9BN BOSE BARRACKPORE SDH ICTC UNIT, BN BOSE BARAKPUR, BARAKPUR, PIN‐123 24 PARGANAS (N) 25452106 KOYEL CHOWDHURY 9830689467 ICTC UNIT, BARANAGAR SGH, 104 AK MUKHERJEE RD. PRIYANKA DAS, SRABONI 9836663813, 10 BARANAGAR SGH * 24 PARGANAS (N) 25313221 KOL‐90 SARKAR GHOSH 981071992 11 PANIHATI SGH ICTC UNIT, PANIHATI SGH, SODHPUR, PIN‐110 24 PARGANAS (N) TUSAR KANTI MAJUMDER 9830234660 25956301 ICTC UNIT, SALT LAKE -

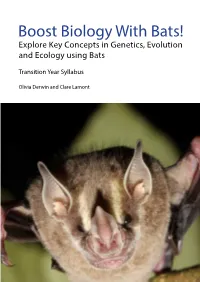

Boost Biology with Bats! Explore Key Concepts in Genetics, Evolution and Ecology Using Bats

Boost Biology With Bats! Explore Key Concepts in Genetics, Evolution and Ecology using Bats Transition Year Syllabus Olivia Derwin and Clare Lamont Contents Overview 3 Why Study Bats? 4 Section 1. Genetics 7 1.1 Cells-the building blocks of all living organisms. 7 1.2 Structure of DNA. 13 1.3 Complementary Base Pairing-Tasks. 25 1.4. Isolating DNA From A Biological Sample. 29 1.5 DNA Replication. 32 1.6 What Are Genes? 33 1.7 The Genetic Code 36 1.8 Protein Synthesis - How are proteins made from a gene? 42 1.9. Genes, Variation, Speciation & Evolution. 48 Section 2. UCD Bat-Lab 55 2.1 Introduction to Bat Lab. 55 2.2 The Steps involved in DNA Analysis. Bat Lab UCD. 56 2.2.1 Extraction and Purification of DNA. 57 2.2.2 PCR - To amplify a gene or DNA sequence. 58 2.2.3 Gel Electrophoresis. 60 Section 3 Comparative Genomics and Phylogenetics 63 3.1 DNA Sequencing 63 3.2 Phylogenetics 69 3.3. Comparitive Biology and Its Uses 74 Section 4. Ecology and Ecosystems 76 4.1 All About Bats 76 4.2 Identification Of Bat Species Through Morphology 79 4.3 Methods Used To Record Bats. 82 4.4 What To Expect From A Bat Walk 83 4.5 Methods For Capturing Bats 84 4.6 The Implications Of Green Energies For Bats And Their Environment. 85 Conclusions 86 Acknowledgements 87 Bibliography 87 Useful weblinks 88 2 Overview Genetics, biochemistry and molecular biology are exciting and progressive areas of science, un- derpinning biology. -

SMM Newsletter Aug2010.Pmd

Small Mammal Mail Newsletter celebrating the most useful yet most neglected Mammals for CCINSA & RISCINSA -- Chiroptera, Rodent, Insectivore, & Scandens Conservation and Information Networks of South Asia Volume 2 Number 1 Jan-Jun 2010 Contents New Network Members Will Fruit Bats be delisted as Vermin on the CCINSA Indian Wildlife Protection Act in the International Year of Biodiversity? If not now, Mr. Manjit Bista when?, Pp. 2-5 Student, Institute of Forestry, Pokhara, Nepal [email protected], [email protected] Small mammals survey in Bhutan, Tenzin, Pp. 6-8 Mr. Muhammad Asif Khan Research Associate, Pakistan Museum of Natural History, A Note on Feeding Habits of Fruit Bats in Colaba, Zoological Sciences Division, Islamabad, Pakistan Urban Mumbai, India, J. Patrick David and [email protected], [email protected] Vidyadhar Atkore, P. 9 RISCINSA Training Report on Bat Capture, Handling and Species Identification, Manjit Bist, Pp. 10-11 Mr. Muhammad Asif Khan Research Associate, Pakistan Museum of Natural History, Training Workshops in South Asia, Pp. 12-15 Zoological Sciences Division, Islamabad, Pakistan [email protected], [email protected] An Updated Checklist of valid bat species of Nepal, Sanjan Thapa, Pp. 16-17 In CCINSA and RISCINA we have never passed a Field Notes on albinism in Five-striped Palm period of six months (and actually it is now eight Squirrel Funambulus pennanti Wroughton from months) between newsletters and had so few new Udaipur, Rajasthan, India, Satya Prakash Mehra, members. Either we have everybody who is Narayan Singh Kharwar, Partap Singh, P. 18 interested in bats and rats already a member (VERY unlikely) or we have lost our reach into the academic Short Report on First One-day National Seminar and nature study institutions that have provided our on Small Mammals Issues, Sagar Dahal and current collection of members. -

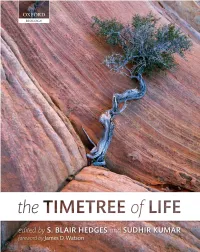

Teeling2009chap78.Pdf

Bats (Chiroptera) Emma C. Teeling oldest bat fossils (~55 Ma) and is considered a microbat; UCD School of Biology and Environmental Science, Science Center however, the majority of the bat fossil record is fragmen- West, University College Dublin, Belfi eld, Dublin 4, Ireland (emma. tary and missing key species (6, 7). Here I review the rela- [email protected]) tionships and divergence times of the extant families of bats. Abstract Traditionally bats have been divided into two super- ordinal groups: Megachiroptera and Microchiroptera Bats are grouped into 17–18 families (>1000 species) within (see 8, 9 for reviews). Megachiroptera was consid- the mammalian Order Chiroptera. Recent phylogenetic ered basal and contained the Old World megabat fam- analyses of molecular data have reclassifi ed Chiroptera at ily Pteropodidae, whereas Microchiroptera contained the interfamilial level. Traditionally, the non-echolocating the 17 microbat families (8, 9). Although this division megabats (Pteropodidae) have been considered to be the was based mainly on morphological and paleonto- earliest diverging lineage of living bats; however, they are logical data, it highlighted the diB erence in mode of now found to be the closest relatives of the echolocating sensory perception between megabats and microbats. rhinolophoid microbats. Four major groups of echolocating Because all microbats are capable of sophisticated laryn- microbats are supported: rhinolophoids, emballonuroids, geal echolocation whereas megabats are not (5), it was vespertilionoids, and noctilionoids. The timetree suggests believed that laryngeal echolocation had a single origin that the earliest divergences among bats occurred ~64 in the lineage leading to microbats (10). 7 e 17 families million years ago (Ma) and that the four major microbat of microbats have been subsequently divided into two lineages were established by 50 Ma. -

The Evolution and Development of Chiropteran Flight

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Honors Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Spring 2020 The Evolution and Development of Chiropteran Flight Emmaline Willis University of New Hampshire Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/honors Part of the Developmental Biology Commons, Evolution Commons, Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Willis, Emmaline, "The Evolution and Development of Chiropteran Flight" (2020). Honors Theses and Capstones. 538. https://scholars.unh.edu/honors/538 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Willis 1 Emmaline Willis Zool Thesis Advisor- Bolker 9/25/19 The Evolution and Development of Chiropteran Flight Intro Flying is thought of as a reserved skill used by very few animals throughout history. These animals may be the birds outside your window, the pterodactyl in a children’s book, or the insects buzzing about on a hot day. There are also thousands of bats flapping around in the dark all around the world. Exploring the sky, bats are the only mammal capable of true powered flight (Gunnel and Simmons 2005). Bats are an extraordinarily diverse group of mammals. Chiroptera, the order name for this group of mammals, has over one thousand species (Hill, 2018). In fact, the number may be closer to 1,400 species (K. -

Decoding Bat Immunity: the Need for a Coordinated Research Approach

COMMENT Decoding bat immunity: the need for a coordinated research approach Lin- Fa Wang 1,2 ✉, Akshamal M. Gamage1, Wharton O. Y. Chan 1, Michael Hiller3,4,5 and Emma C. Teeling6 Understanding antiviral immune responses in bats, which are reservoirs for many emerging viruses, could aid the response to future epidemics. Here, we discuss five key areas in which greater consensus among the bat research community is necessary to drive breakthroughs in the field. With more than 1,400 species that collectively account currently available for approximately 50 bat species, and for ~20% of all living mammals, bats serve as a rich on- going efforts by the Bat1K consortium to generate resource for understanding mammalian evolution and reference- quality genomes for all living bat species7 will adaptation1. Bats belong to the Chiroptera order and are provide a much needed foundational resource for the the only mammals capable of self- powered flight. They subsequent development of immunological tools. are also remarkably diverse in terms of their physiology, The availability of bat- derived cell lines has also ena- social biology, sensory perception, ecological habitats bled in vitro experimentation and hypothesis testing8. and diet. In recent years, bats have garnered attention as Transcriptomic and molecular studies using cell lines suspected reservoirs for viruses that can cause disease have provided novel insights into how bat cells respond in humans, including the SARS- related coronaviruses2. to infection. However, despite being an accessible and This observation has been attributed to a tolerant (that tractable resource, bat cell lines have several limitations, is, non- pathological) bat immune response to these including the lack of complex cell interactions that are viruses3, as well as to the high species diversity within present in vivo and artefacts imposed by the process the chiropteran order4.