Cardiovascular Risk After Hospitalisation for Unexplained

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stroke Mimics and Chameleons: Quandaries in the Field

Stroke Mimics and Chameleons: Quandaries in the Field Madeleine Geraghty, MD Rockwood Multicare What’s the difference Stroke mimic: Looks like a stroke, is something else Stroke chameleon: Looks like something else, is really a stroke! Scope of the Mimic Recent eval by Briard, et al: ◦ 960 patients transported by EMS during an 18 month period ◦ 42% mimics 55% other neurologic diagnoses 20% seizures, 19% migraines, 11% peripheral neuropathies 45% non-neurologic diagnoses Cardiac 16%, psychiatric 12%, infectious 9% ◦ Neurologic mimics were younger (~64 years) than non-neurologic mimics (~70 years) Entering a new era Large vessel occlusions Now a 24 hour time window for mechanical thrombectomy ◦ Most centers will likely activate the > 6 hour patients from within the ED, still working out those details Volume of stroke mimics/chameleons in the new time window? Effects on resource management? ◦ At the hospital level? ◦ At the regional level with distance transports? Need Emergency Responder Impressions now more than ever in order to learn for the future!! General Principles Positive symptoms Indicate an excess of central nervous system neuron electrical discharges Visual: flashing lights, zig zag shapes, lines, shapes, objects sensory: paresthesia, pain motor: jerking limb movements Migraine, Seizure are characterized with having “positive” symptoms Negative symptoms Indicate a loss or reduction of central nervous system neuron function – loss of vision, hearing, sensation, limb power. TIA/Stroke present with “negative” symptoms. -

Syncope Fainting, Or Syncope, Is the Sudden Loss of Consciousness and Ability to Stand

Northwestern Memorial Hospital Patient Education CONDITIONS AND DISEASES Syncope Fainting, or syncope, is the sudden loss of consciousness and ability to stand. It is also called “passing out.” This common If you have any problem is the cause of many falls and injuries. One third of people faint at least once during their life. Syncope may occur questions, ask without warning or can be signaled by: ■ Feelings of weakness your physician ■ Feeling hot or sweating ■ Dizziness or nurse. ■ Visual changes ■ Nausea ■ Palpitations Causes of syncope Fainting is due to a sudden decrease in blood flow and oxygen to the brain. There are many causes of syncope, but most fall into 1 of 3 major types. Abnormal nerve reflex Nerves that control heart rate, blood pressure and other body functions may respond in an abnormal way and cause syncope. This can be triggered by: ■ Standing ■ Pain ■ Unpleasant sight or smell ■ Stress, anxiety or emotional distress ■ Coughing, sneezing or swallowing ■ Urinating or having a bowel movement Fainting due to an abnormal nerve reflex is more likely to occur under certain conditions, such as dehydration, viral infection, after prolonged bed rest or a lack of sleep or regular food intake. Types of syncope that involve an abnormal nerve reflex include: ■ Vasovagal (neurocardiac) syncope is the most common type and can occur at any age. It often occurs when blood pools in the leg veins. This triggers a reflex where the heart rate, blood pressure or both may suddenly fall. It generally is not a dangerous condition and can be prevented by avoiding situations that can trigger syncope. -

Latest Diagnostic and Treatment Strategies for the Congenital Long QT Syndromes

Latest Diagnostic and Treatment Strategies for the Congenital Long QT Syndromes Michael J. Ackerman, MD, PhD Windland Smith Rice Cardiovascular Genomics Research Professor Professor of Medicine, Pediatrics, and Pharmacology Director, Long QT Syndrome Clinic and the Mayo Clinic Windland Smith Rice Sudden Death Genomics Laboratory President, Sudden Arrhythmia Death Syndromes (SADS) Foundation Learning Objectives to Disclose: • To RECOGNIZE the “faces” (phenotypes) of the congenital long QT syndromes (LQTS) • To CRITIQUE the various diagnostic modalities used in the evaluation of LQTS and UNDERSTAND their limitations • To ASSESS the currently available treatment options for the various LQT syndromes and EVALUATE their efficacy WINDLAND Smith Rice Sudden Death Genomics Laboratory Conflicts of Interest to Disclose: • Consultant – Boston Scientific, Gilead Sciences, Medtronic, St. Jude Medical, and Transgenomic/FAMILION • Royalties – Transgenomic/FAMILION Congenital Long QT Syndrome Normal QT interval QT QT Prolonged QT 1. Syncope 2. Seizures 3. Sudden death Torsades de pointes Congenital Long QT Syndrome Normal QT interval QT QT ♥ 1957 – first clinical description – JLNS ♥ 1960s – RomanoProlonged-Ward QT syndrome ♥ 1983 – “Schwartz/Moss score”1. Syncope ♥ 1991 – first LQTS chromosome locus 2. Seizures ♥ March 10, 1995 – birth of cardiac 3. Sudden channelopathies death Torsades de pointes Congenital Long QT Syndrome Normal QT interval QT QT Prolonged QT 1. Syncope 2. Seizures 3. Sudden death Torsades de pointes Congenital Long QT Syndrome Normal -

TREATMENT of VASOVAGAL SYNCOPE Where to Go for Help Syncope: HRS Definition

June 8, 2018, London UK TREATMENT OF VASOVAGAL SYNCOPE Where to go for help Syncope: HRS Definition ▪ Syncope is defined as: —a transient loss of consciousness, —associated with an inability to maintain postural tone, —rapid and spontaneous recovery, —and the absence of clinical features specific for another form of transient loss of consciousness such as epileptic seizure. 3 Syncope Cardiac Vasovagal Orthostatic Carotid sinus 4 Vasovagal Syncope: HRS Definition ▪ Vasovagal syncope is defined as a syncope syndrome that usually: 1. occurs with upright posture held for more than 30 seconds or with exposure to emotional stress, pain, or medical settings; 2. features diaphoresis, warmth, nausea, and pallor; 3. is associated with hypotension and relative bradycardia, when known; and 4. is followed by fatigue. 5 Physiology of Symptoms and Signs Decreased cardiac output Hypotension • Weakness • Lightheadness Retinal hypoperfusion • Blurred vision, grey vision, coning down Physiology of Symptoms and Signs Decreased cardiac output Reflex cutaneous vasoconstriction • Maintains core blood volume • Pallor, looks grey or very white Physiology of Symptoms and Signs Vasovagal reflex Worsened hypotension • More weakness • More lightheadness Vagal • Nausea and vomiting • Diarrhea • Abdominal discomfort Physiology of Symptoms and Signs Increase arterial conductance Rapid transit of core blood to skin • Hot flash • Warmth and discomfort • Lasts seconds • Pink skin SYNCOPE 9 Physiology of Symptoms and Signs Collapse • Preload restored • Reflexes end • Skin -

Update on the Diagnosis and Management of Familial Long QT Syndrome

Heart, Lung and Circulation (2016) 25, 769–776 POSITION STATEMENT 1443-9506/04/$36.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2016.01.020 Update on the Diagnosis and Management of Familial Long QT Syndrome Kathryn E Waddell-Smith, FRACP a,b, Jonathan R Skinner, FRACP, FCSANZ, FHRS, MD a,b*, members of the CSANZ Genetics Council Writing Group aGreen Lane Paediatric and Congenital Cardiac Services, Starship Children’s Hospital, Auckland New Zealand bDepartment[5_TD$IF] of Paediatrics,[6_TD$IF] Child[7_TD$IF] and[8_TD$IF] Youth[9_TD$IF] Health,[10_TD$IF] University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand Received 17 December 2015; accepted 20 January 2016; online published-ahead-of-print 5 March 2016 This update was reviewed by the CSANZ Continuing Education and Recertification Committee and ratified by the CSANZ board in August 2015. Since the CSANZ 2011 guidelines, adjunctive clinical tests have proven useful in the diagnosis of LQTS and are discussed in this update. Understanding of the diagnostic and risk stratifying role of LQTS genetics is also discussed. At least 14 LQTS genes are now thought to be responsible for the disease. High-risk individuals may have multiple mutations, large gene rearrangements, C-loop mutations in KCNQ1, transmembrane mutations in KCNH2, or have certain gene modifiers present, particularly NOS1AP polymorphisms. In regards to treatment, nadolol is preferred, particularly for long QT type 2, and short acting metoprolol should not be used. Thoracoscopic left cardiac sympathectomy is valuable in those who cannot adhere to beta blocker therapy, particularly in long QT type 1. Indications for ICD therapies have been refined; and a primary indication for ICD in post-pubertal females with long QT type 2 and a very long QT interval is emerging. -

Premature Ventricular Contractions Ralph Augostini, MD FACC FHRS

Premature Ventricular Contractions Ralph Augostini, MD FACC FHRS Orlando, Florida – October 7-9, 2011 Premature Ventricular Contractions: ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death J Am Coll Cardiol, 2006; 48:247-346. Background PVCs are ectopic impulses originating from an area distal to the His Purkinje system Most common ventricular arrhythmia Significance of PVCs is interpreted in the context of the underlying cardiac condition Ventricular ectopy leading to ventricular tachycardia (VT), which, in turn, can degenerate into ventricular fibrillation, is one of the common mechanisms for sudden cardiac death The treatment paradigm in the 1970s and 1980s was to eliminate PVCs in patients after myocardial infarction (MI). CAST and other studies demonstrated that eliminating PVCs with available anti-arrhythmic drugs increases the risk of death to patients without providing any measurable benefit Pathophysiology Three common mechanisms exist for PVCs, (1) automaticity, (2) reentry, and (3) triggered activity: Automaticity: The development of a new site of depolarization in non-nodal ventricular tissue. Reentry circuit: Reentry typically occurs when slow- conducting tissue (eg, post-infarction myocardium) is present adjacent to normal tissue. Triggered activity: Afterdepolarization can occur either during (early) or after (late) completion of repolarization. Early afterdepolarizations commonly are responsible for bradycardia associated PVCs, but also with ischemia and electrolyte disturbance. Triggered Fogoros: Electrophysiologic Testing. 3rd ed. Blackwell Scientific 1999; 158. Epidemiology Frequency The Framingham heart study (with 1-h ambulatory ECG) 1 or more PVCs per hour was 33% in men without coronary artery disease (CAD) and 32% in women without CAD Among patients with CAD, the prevalence rate of 1 or more PVCs was 58% in men and 49% in women. -

Syncope: Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis LLOYD A

Syncope: Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis LLOYD A. RUNSER, MD, MPH; ROBERT L. GAUER, MD; and ALEX HOUSER, DO Womack Army Medical Center, Fort Bragg, North Carolina Syncope is an abrupt and transient loss of consciousness caused by cerebral hypoperfusion. It accounts for 1% to 1.5% of emergency department visits, resulting in high hospital admission rates and significant medical costs. Syncope is classified as neurally mediated, cardiac, and orthostatic hypotension. Neurally mediated syncope is the most common type and has a benign course, whereas cardiac syncope is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Patients with presyncope have similar prognoses to those with syncope and should undergo a similar evaluation. A standard- ized approach to syncope evaluation reduces hospital admissions and medical costs, and increases diagnostic accu- racy. The initial assessment for all patients presenting with syncope includes a detailed history, physical examination, and electrocardiography. The initial evaluation may diagnose up to 50% of patients and allows immediate short-term risk stratification. Laboratory testing and neuroimaging have a low diagnostic yield and should be ordered only if clin- ically indicated. Several comparable clinical decision rules can be used to assess the short-term risk of death and the need for hospital admission. Low-risk patients with a single episode of syncope can often be reassured with no further investigation. High-risk patients with cardiovascular or structural heart disease, history concerning for arrhythmia, abnormal electrocardiographic findings, or severe comorbidities should be admitted to the hospital for further evalu- ation. In cases of unexplained syncope, provocative testing and prolonged electrocardiographic monitoring strategies can be diagnostic. -

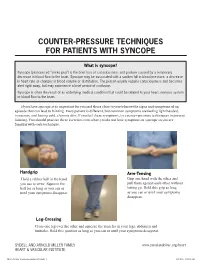

Counter-Pressure Techniques for Patients with Syncope

COUNTER-PRESSURE TECHNIQUES FOR PATIENTS WITH SYNCOPE What is syncope? Syncope (pronounced “sin ko pea”) is the brief loss of consciousness and posture caused by a temporary decrease in blood flow to the brain. Syncope may be associated with a sudden fall in blood pressure, a decrease in heart rate or changes in blood volume or distribution. The person usually regains consciousness and becomes alert right away, but may experience a brief period of confusion. Syncope is often the result of an underlying medical condition that could be related to your heart, nervous system or blood flow to the brain. If you have syncope, it is important for you and those close to you to know the signs and symptoms of an episode that can lead to fainting. Every patient is different, but common symptoms are feeling light headed, nauseous, and having cold, clammy skin. If you feel these symptoms, try counter-pressure techniques to prevent fainting. You should practice these exercises even when you do not have symptoms of syncope so you are familiar with each technique. Handgrip Arm-Tensing Hold a rubber ball in the hand Grip one hand with the other and you use to write. Squeeze the pull them against each other without ball for as long as you can or letting go. Hold this grip as long until your symptoms disappear. as you can or until your symptoms disappear. Leg-Crossing Cross one leg over the other and squeeze the muscles in your legs, abdomen and buttocks. Hold this position as long as you can or until your symptoms disappear. -

Near-Syncope After Exercise

GRAND ROUNDS CLINICIAN’S CORNER AT THE JOHNS HOPKINS BAYVIEW MEDICAL CENTER Near-Syncope After Exercise Roy C. Ziegelstein, MD Syncope and near-syncope are great diagnostic challenges in medicine. On CASE PRESENTATION the one hand, the symptom may result from a benign condition and pose A 72-year-old man complained of near- little or no threat to health other than that related to falling. On the other syncope after exercise that had been oc- hand, syncope or near-syncope can be the manifestation of a serious un- curring for several months. Every morn- derlying condition that poses an imminent threat to life. Patients with a car- ing, he walked at 3.5 mph for about half diac cause of syncope are at far greater risk of dying in the first year after an an hour on his treadmill in the well- ventilated basement of his home. After episode of syncope or near-syncope than individuals with a noncardiac cause. exercising, he would step off the tread- A cardiac cause of syncope should be considered in every patient with syn- mill, check his pulse, and become light- cope or near-syncope, but it is particularly common in older patients or in headed immediately afterward. This feel- patients with known structural heart disease, arrhythmia, or certain electro- ing lasted a few minutes and he would cardiographic abnormalities. Although many diagnostic tests may be help- then go upstairs to eat breakfast and take ful in the evaluation of syncope and near-syncope, the history, physical ex- his medications. amination, and electrocardiogram pinpoint the cause in many circumstances. -

A Case of Long-QT Syndrome Presenting After Childbirth Ryan Wereski1, Richard Dobson2, Edward J Newman3, Derek Connelly4

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2019; 49: 26–30 | doi: 10.4997/JRCPE.2019.105 CASE REPORT Syncope in a new mother: a case of long-QT syndrome presenting after childbirth Ryan Wereski1, Richard Dobson2, Edward J Newman3, Derek Connelly4 ClinicalDiagnosis of inherited arrhythmia syndromes, including long-QT syndrome Correspondence to: (LQTS), is challenging; however, early detection and initiation of therapies Ryan Wereski Abstract can reduce otherwise high rates of mortality. Department of Cardiology Queen Elizabeth University Two months following the birth of her rst child a previously well 21-year-old Hospital female experienced four episodes of transient loss of consciousness (TLOC). 1345 Govan Road The history was atypical for seizures but a video electroencephalogram (EEG) captured an Glasgow G51 4TF episode with abnormal bifrontal epileptic discharge. She was commenced on levetiracetam. UK Within weeks of the birth of her second child she experienced ve further episodes. During the Email: subsequent hospital admission an electrocardiogram (ECG) recorded polymorphic ventricular [email protected] tachycardia (VT) during a typical TLOC event. Other ECGs recorded a prolonged QT interval. A diagnosis of LQTS was made and TLOC episodes ceased on commencement of nadolol. The patient experienced 22 TLOC episodes before diagnosis – most likely from self-terminating VT. With widespread availability of effective treatments to reduce the risk of sudden cardiac death in such conditions, clinicians should always remember how the ECG is an essential investigation every time a patient presents with TLOC. Keywords: diagnosis, EEG, long-QT syndrome, LQTS, post-partum, pregnancy Financial and Competing Interests: No confl ict of interests declared Introduction demonstrates the importance of the electrocardiogram (ECG) Inherited arrhythmia syndromes including long-QT syndrome in the assessment of all patients with TLOC and how the ECG (LQTS) are a common cause of sudden unexplained death should always be a central investigation. -

Symptoms and Signs Associated with Syncope in Young People

ARTICLE Original Article ORIGINAL Symptoms and Signs Associated with Syncope in Young People with Primary Cardiac Arrhythmias a,b,c a,b Judith M. MacCormick, MBChB , Jackie R. Crawford, NZCS , d b,e b,e Seo-Kyung Chung, PhD , Andrew N. Shelling, PhD , Cary-Anne Evans, MSc (Med) , b,d a,b b,f Mark I. Rees, PhD , Warren M. Smith, MBChB , Ian G. Crozier, MBChB , b,g a,b,∗ Hugh McAlister and Jon R. Skinner, MD a Green Lane Paediatric and Congenital Cardiac Service, Auckland City/Starship Children’s Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand b Cardiac Inherited Diseases Group (CIDG), Auckland City/Starship Children’s Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand c Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston, MA, United States d Institute of Life Science, School of Medicine, Swansea University, Swansea, United Kingdom e Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand f Department of Cardiology, Christchurch Hospital, New Zealand g Department of Cardiology, Waikato Hospital, New Zealand Background: It is often reported that clinical symptoms are useful in differentiating cardiac from non-cardiac syncope. Studies in the young are rare. This study was designed to capture the symptoms and signs reported by patients with cardiac syncope before the patients or their attending clinicians knew the final diagnosis. Methods: Retrospective case-note review of 35 consecutive unrelated gene-positive probands with a proven cardiac channelopathy. Results: The presentation leading to diagnosis of cardiac channelopathy was resuscitated sudden cardiac death in 7 patients; syncope in 20; collapse with retained consciousness in 2; palpitations in 1 and an incidental finding in 5. -

Neurally Mediated Syncope Manifesting During Atrial Fibrillation a Case Report

Circ J 2002; 66: 866–868 Neurally Mediated Syncope Manifesting During Atrial Fibrillation A Case Report Takeshi Shirayama, MD; Keiji Inoue, MD; Takashi Sakamoto, MD; Midori Yamamura, MD; Hiroki Mani, MD; Akiko Yoshida, MD; Hiroto Imai, MD; Yayoi Matoba, MD; Masao Nakagawa, MD A 64-year-old male was admitted to hospital because of repeated episodes of syncope and palpitation. Ambulatory monitoring revealed paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF) as the cause of palpitation; he did not have structural heart disease. The induction of AF by rapid pacing (50Hz for 1s) in an upright position provoked syncope with a vasodepressor response. Atropine sulfate blocked the induction of syncope. The possible etiology was neurally mediated syncope that manifested only during AF, which suggests that the abnormal vagal activity during AF in this case exaggerated the vasodepessor response while upright. (Circ J 2002; 66: 866–868) Key Words: Atrial fibrillation; Head-up tilt; Neurally mediated syncope; Vagal nerve yncope is often encountered in an emergency room, Laboratory tests revealed hyperlipidemia (triglyceride, but its etiology is not always clear. Neurally medi- 240mg/dl; total cholesterol, 208mg/dl) and hyperuricemia S ated syncope, which is characterized by abnormal (8.6 mg/dl). Liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase, vagal reflex, has been recently recognized as a major cause alanine aminotransferase,γ-glutamyl transpeptidase) were of syncopal episodes,1–3 and it can be provoked repeatedly normal. Blood pressure was 132/70mmHg, and heart rate by the head-up tilt test with fairly good sensitivity.2,4 A was regular at 85beats/min. The ECG was normal, as was paroxysmal attack of atrial fibrillation (AF) is another ultrasonic echocardiography.