Partial Anodontia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral Health in Prevalent Types of Ehlers–Danlos Syndromes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography J Oral Pathol Med (2005) 34: 298–307 ª Blackwell Munksgaard 2005 Æ All rights reserved www.blackwellmunksgaard.com/jopm Oral health in prevalent types of Ehlers–Danlos syndromes Peter J. De Coster1, Luc C. Martens1, Anne De Paepe2 1Department of Paediatric Dentistry, Centre for Special Care, Paecamed Research, Ghent University, Ghent; 2Centre for Medical Genetics, Ghent University Hospital, Ghent, Belgium BACKGROUND: The Ehlers–Danlos syndromes (EDS) Introduction comprise a heterogenous group of heritable disorders of connective tissue, characterized by joint hypermobility, The Ehlers–Danlos syndromes (EDS) comprise a het- skin hyperextensibility and tissue fragility. Most EDS erogenous group of heritable disorders of connective types are caused by mutations in genes encoding different tissue, largely characterized by joint hypermobility, skin types of collagen or enzymes, essential for normal pro- hyperextensibility and tissue fragility (1) (Fig. 1). The cessing of collagen. clinical features, modes of inheritance and molecular METHODS: Oral health was assessed in 31 subjects with bases differ according to the type. EDS are caused by a EDS (16 with hypermobility EDS, nine with classical EDS genetic defect causing an error in the synthesis or and six with vascular EDS), including signs and symptoms processing of collagen types I, III or V. The distribution of temporomandibular disorders (TMD), alterations of and function of these collagen types are displayed in dental hard tissues, oral mucosa and periodontium, and Table 1. At present, two classifications of EDS are was compared with matched controls. -

2021 Follow-Up After Emergency Department Visits for Non-Traumatic Dental Conditions in Adults

DQA Measure EDF-A-A Effective January 1, 2021 **Please read the DQA Measures User Guide prior to implementing this measure.** DQA Measure Specifications: Administrative Claims-Based Measures Follow-up after Emergency Department Visits for Non-Traumatic Dental Conditions in Adults Description: The percentage of ambulatory care sensitive non-traumatic dental condition emergency department visits among adults aged 18 years and older in the reporting period for which the member visited a dentist within (a) 7 days and (b) 30 days of the ED visit Numerators: Number of ambulatory care sensitive non-traumatic dental condition ED visits in the reporting period for which the member visited a dentist within (a) 7 days (NUM1) and (b) 30 days (NUM2) of the ED visit Denominator: Number of ambulatory care sensitive non-traumatic dental condition ED visits in the reporting period Rates: NUM1/DEN and NUM2/DEN Rationale: The use of emergency departments (EDs) for non-traumatic dental conditions has been a growing public health concern across the United States (US)1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 with over 2 million visits occurring in 2015.9 The majority of ED visits are semi-urgent (53.8%) or non-urgent (23.9%)10, which can be better managed in an ambulatory care setting. Dental care in an ED setting is not definitive with limited care continuity that ultimately leads to poor oral health outcomes.11,12,13 This process of care measure can be used to assess if the patient had timely follow-up with a dentist for more definitive care. References: 1. -

Non-Syndromic Occurrence of True Generalized Microdontia with Mandibular Mesiodens - a Rare Case Seema D Bargale* and Shital DP Kiran

Bargale and Kiran Head & Face Medicine 2011, 7:19 http://www.head-face-med.com/content/7/1/19 HEAD & FACE MEDICINE CASEREPORT Open Access Non-syndromic occurrence of true generalized microdontia with mandibular mesiodens - a rare case Seema D Bargale* and Shital DP Kiran Abstract Abnormalities in size of teeth and number of teeth are occasionally recorded in clinical cases. True generalized microdontia is rare case in which all the teeth are smaller than normal. Mesiodens is commonly located in maxilary central incisor region and uncommon in the mandible. In the present case a 12 year-old boy was healthy; normal in appearance and the medical history was noncontributory. The patient was examined and found to have permanent teeth that were smaller than those of the average adult teeth. The true generalized microdontia was accompanied by mandibular mesiodens. This is a unique case report of non-syndromic association of mandibular hyperdontia with true generalized microdontia. Keywords: Generalised microdontia, Hyperdontia, Permanent dentition, Mandibular supernumerary tooth Introduction [Ullrich-Turner syndrome], Chromosome 13[trisomy 13], Microdontia is a rare phenomenon. The term microdontia Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, Hallermann-Streiff, Oro- (microdentism, microdontism) is defined as the condition faciodigital syndrome (type 3), Oculo-mandibulo-facial of having abnormally small teeth [1]. According to Boyle, syndrome, Tricho-Rhino-Phalangeal, type1 Branchio- “in general microdontia, the teeth are small, the crowns oculo-facial syndrome. short, and normal contact areas between the teeth are fre- Supernumerary teeth are defined as any supplementary quently missing” [2] Shafer, Hine, and Levy [3] divided tooth or tooth substance in addition to usual configuration microdontia into three types: (1) Microdontia involving of twenty deciduous and thirty two permanent teeth [7]. -

Ovarian Cancer

113th AAO Annual Session OVERVIEW Unraveling an Association between Hypodontia and OUTLINE Epithelial Ovarian Cancer 1. Introduction Anna N Vu, DMD, MS 2. Background 3. Purpose Division of Orthodontics 4. Materials and Methods May 2013 5. Results 6. Discussion 7. Conclusion U N I V E R S I T Y O F K E N T U C K Y C O L L E G E O F D E N T I S T R Y HYPODONTIA HYPODONTIA REVIEW & CANCER • Over 300 genes are involved in odontogenesis including MSX1, PAX9, and AXIN2 HYPODONTIA • Genes involved in dental development also have roles in other organs of the body Defined as the developmental absence of one or more teeth as well as variations in size, • Mutation in several genes governing tooth development have already been associated with shape, rate of dental development and eruption time. cancer • Mutations in AXIN2 cause familial tooth agenesis and predispose to colorectal cancer7 Hypodontia is the agenesis of 6 or less teeth. • AXIN2 gene is highly expressed in ovarian tissue so may play a role in epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC)8 Oligodontia is the agenesis of 6 or more teeth. Anodontia is the agenesis of all teeth. • Reduced expression of PAX9 can lead to hypodontia and has been correlated with increased malignancy of dysplastic and cancerous esophageal epithelium9 2.6-11.3% reported prevelance worldwide. 78 • RUNX transcription factor family (RUNX1, 2, and 3) are involved in odontogenesis and has been Women are affected more than males at a ratio of 3:2. the most targeted genes in acute myeloid leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia10 Both genetic and environmental explanations for hypodontia have been reported. -

Concomitant Mandibular Hypo-Hyperdontia: Report of Two Rarest Cases with the Literature Review

International Journal of Contemporary Dental and Medical Reviews (2014), Article ID 091214, 6 Pages REVIEW ARTICLE Concomitant mandibular hypo-hyperdontia: Report of two rarest cases with the literature review N. B. Nagaveni, Meghna Bajaj, Kirthiga Muthusamy, P. Poornima, Suryakanth M. Pai, V. V. Subba Reddy Department of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry, College of Dental Sciences, Davangere, Karnataka, India Correspondence Abstract Dr. N.B. Nagaveni, Department of Pedodontics Concomitant occurrence of both hypodontia (congenital tooth agenesis) and and Preventive Dentistry, College of Dental hyperdontia (supernumerary tooth) in the same dental arch is an extremely rare dental Sciences, Davangere, Karnataka, India. Email: anomaly. Literature search shows very few cases of this anomalous condition with all [email protected] cases depicting the unilateral presence of supernumerary tooth. Therefore, the intention Received 16 December 2014; of the current article is to report two cases of concomitant occurrence of mandibular both Accepted 18 January 2015 hypo-hyperdontia. In that one case exhibited bilateral occurrence of mesiodens teeth in the midline of mandible with associated agenesis of permanent both central incisors doi: 10.15713/ins.ijcdmr.22 and taurodontism in permanent molars, which is not published so far. The article also provides comprehensive literature review on this rarest clinical entity. How to cite the article: N. B. Nagaveni, Meghna Bajaj, Kirthiga Keywords: Mandibular mesiodens, supernumerary tooth, tooth agenesis Muthusamy, P. Poornima, Suryakanth M. Pai, V. V. Subba Reddy, “Concomitant mandibular hypo-hyperdontia: Report of two rarest cases with literature review”, Int J Contemp Dent Med Rev, Vol. 2014, Article ID: 091214, 2014. doi: 10.15713/ins.ijcdmr.22 Introduction same patient. -

Emergency Department Visits Involving Dental Conditions, 2018

HEALTHCARE COST AND Agency for Healthcare UTILIZATION PROJECT Research and Quality Emergency Department Visits Involving Dental Conditions, 2018 STATISTICAL BRIEF #280 August 2021 Highlights ■ In 2018, there were more than 2 Pamela L. Owens, Ph.D., Richard J. Manski, D.D.S., M.B.A., million dental-related Ph.D., and Audrey J. Weiss, Ph.D. emergency department (ED) visits, which represented 615.5 Introduction visits per 100,000 population. Oral health contributes to overall wellbeing and improved quality ■ The highest population rates of of life. Untreated poor dental health also can lead to negative dental-related ED visits were general health outcomes.1 Most oral diseases tend to be among non-Hispanic Black progressive and cumulative without intervention.2 Tooth decay individuals, individuals aged 18– and periodontal disease are among the most prevalent chronic 44 years, and those residing in diseases worldwide and have been shown to be associated with the lowest income communities, a number of life-threatening conditions, including sepsis, (rates of 1,362.4, 1,107.4, and diabetes, and heart disease.2,3 Despite the increasing need for 1,069.1 per 100,000 population, dental care, many Americans delay or do not receive it. Failure to respectively). receive treatment may make necessary the provision of less ■ A higher proportion of dental- definitive and more costly care. Individuals who lack a usual related than non-dental-related source for dental care may visit hospital emergency departments ED visits were expected to be 4,5 (EDs) to seek relief for dental pain and related conditions. The paid by Medicaid (42 vs. -

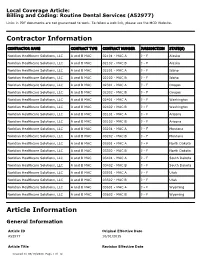

Billing and Coding: Routine Dental Services Local Coverage Article

Local Coverage Article: Billing and Coding: Routine Dental Services (A52977) Links in PDF documents are not guaranteed to work. To follow a web link, please use the MCD Website. Contractor Information CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT NUMBER JURISDICTION STATE(S) Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC A and B MAC 02101 - MAC A J - F Alaska Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC A and B MAC 02102 - MAC B J - F Alaska Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC A and B MAC 02201 - MAC A J - F Idaho Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC A and B MAC 02202 - MAC B J - F Idaho Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC A and B MAC 02301 - MAC A J - F Oregon Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC A and B MAC 02302 - MAC B J - F Oregon Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC A and B MAC 02401 - MAC A J - F Washington Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC A and B MAC 02402 - MAC B J - F Washington Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC A and B MAC 03101 - MAC A J - F Arizona Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC A and B MAC 03102 - MAC B J - F Arizona Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC A and B MAC 03201 - MAC A J - F Montana Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC A and B MAC 03202 - MAC B J - F Montana Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC A and B MAC 03301 - MAC A J - F North Dakota Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC A and B MAC 03302 - MAC B J - F North Dakota Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC A and B MAC 03401 - MAC A J - F South Dakota Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC A and B MAC 03402 - MAC B J - F South Dakota Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC A and B MAC 03501 - MAC A J - F Utah Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC A and B MAC 03502 - MAC B J - F Utah Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC A and B MAC 03601 - MAC A J - F Wyoming Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC A and B MAC 03602 - MAC B J - F Wyoming Article Information General Information Article ID Original Effective Date A52977 10/01/2015 Article Title Revision Effective Date Created on 05/19/2020. -

On the Genetics of Hypodontia and Microdontia: Synergism Or Allelism of Major Genes in a Family with Six Affected Members

JMed Genet 1996;33:137-142 137 On the genetics of hypodontia and microdontia: synergism or allelism of major genes in a family J Med Genet: first published as 10.1136/jmg.33.2.137 on 1 February 1996. Downloaded from with six affected members S P Lyngstadaas, H Nordbo, T Gedde-Dahl Jr, P S Thrane Abstract and epigenetic factors.7 In a large study oftooth Familial severe hypodontia of the per- number and size in British schoolchildren, ex- manent dentition is a rare condition. The cluding patients with more widespread ab- genetics ofthis entity remains unclear and normalities, Brook3 favoured a multifactorial several modes of inheritance have been model with a continuous spectrum, related to suggested. We report here an increase in tooth number and size, with thresholds, and the number of congenitally missing teeth where position on the scale depends upon the after the mating of affected subjects from combination of numerous genetic and en- two unrelated Norwegian families. This vironmental factors, each with a small effect. condition may be the result of allelic mut- In this study the proportion ofaffected relatives ations at a single gene locus. Alternatively, varied with the severity of the condition in the incompletely penetrant non-allelic genes probands and an association between hy- may show a synergistic effect as expected podontia and microdontia was noted. for a multifactorial trait with interacting Other causes of hypodontia have been sug- gene products. This and similar kindreds gested and include an evolutionary trend to- may allow identification of genes involved wards fewer teeth,28 infections during in growth and differentiation of dental tis- pregnancy and early childhood, hormonal dys- sues by linkage and haplotype association function, which itself may be inherited, and analysis. -

The Investigation of Major Salivary Gland Agenesis: a Case Report

Oral Pathology The investigation of major salivary gland agenesis: A case report T.A. Hodgson FDS, RCS, MRCP(UK) R. Shah FDS, RCS S.R. Porter MD, PhD, FDS, RCS, FDS, RCSE Dr. Hodgson is a specialist registrar and professor, and Dr. Porter is a consultant and head of department, Department of Oral Medicine; Dr. Shah is senior house officer, Department of Pediatric Dentistry , Eastman Dental Institute for Oral Health Care Sciences, University College London. Correspond with Dr. Hodgson at [email protected] Abstract Salivary gland agenesis is an extremely uncommon congenital The present report details a child with rampant dental car- anomaly, which may cause a profound xerostomia in children. The ies secondary to xerostomia. Despite having oral disease for oral sequelae includes dental caries, candidosis, and ascending many years, the congenital absence of all the salivary glands sialadenitits. failed to be established until late adolescence, and, therefore, The present report details a child with rampant dental caries appropriate replacement therapy was not instituted, until this secondary to xerostomia. Despite having oral disease for many years, time, to prevent further oral disease. the congenital absence of all the salivary glands failed to be estab- lished until early adulthood. Case report The appropriate investigation and management of the In 1988, a 41/2-year-old Caucasian female was referred to the xerostomic child allows a definitive diagnosis to be made and at- Department of Pediatric Dentistry of the Eastman Dental In- tention focused on the prevention and treatment of resultant oral stitute for Oral Health Care Sciences for the extraction of disease. -

Radiographic Assessment of Third Molars Agenesis Patterns in Young Adults

Pesquisa Brasileira em Odontopediatria e Clínica Integrada 2021; 21:e0212 https://doi.org/10.1590/pboci.2021.076 ISSN 1519-0501 / eISSN 1983-4632 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Radiographic Assessment of Third Molars Agenesis Patterns in Young Adults Anahat Chugh1 , Komal Smriti1 , Anupam Singh2 , Mathangi Kumar3 , Kalyan Chakravarthy Pentapati1 , Srikanth Gadicherla2 , Chehak Nayyar1 , Shreshth Kapoor4 1Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India. 2Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India. 3Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India. 4Department of Public Health Dentistry, Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India. Correspondence: Komal Smriti, Department of Oral Medicine & Radiology, Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal 576104, Karnataka, India. E-mail: [email protected] Academic Editor: Alessandro Leite Cavalcanti Received: 28 September 2020 / Review: 14 December 2020 / Accepted: 07 January 2021 How to cite: Chugh A, Smriti K, Singh A, Kumar M, Pentapati KC, Gadicherla S, Nayyar C, Kapoor S. Radiographic assessment of third molars agenesis patterns in young adults. Pesqui Bras Odontopediatria Clín Integr. 2021; 21:e0212. https://doi.org/10.1590/pboci.2021.076 ABSTRACT Objective: To determine the prevalence of third molar agenesis and associated characteristics. Material and Methods: A total of 2374 panoramic radiographs were retrieved from the radiological archives and evaluated in a computer monitor under optimum viewing conditions. The basic demographic data (age and sex) and the primary findings regarding the presence or absence of third molars in the maxillary and mandibular arches were recorded systematically in a specially designed proforma. -

University of Illinois, December 2003

Case #1 Case Presented by Virginia C. Fiedler, MD, Michelle Bain, MD and Alexander L. Berlin, MD History of Present Illness: This 9-year-old African American girl presented with hair shedding and patchy hair loss since infancy. Additionally, her hair has been brittle. Her scalp is comfortable, without pruritus. The patient’s mother has also noticed deviations of multiple finger joints since the age of 3 along with more recent similar changes in toe joints. These changes are not associated with pain or joint swelling. The patient denies decreased body sweating, but she does note increased sweating in the areas of scalp hair loss. Past Medical History: Febrile seizures as a child Multiple finger and toe joint deviations starting at 3 years of age History of ankle deformities treated with braces for 2 years Medications: None Allergies: No known drug allergies Family History: No history of autoimmune or other skin disorders; no joint abnormalities Social History: Patient is a 4th grade student and is doing well in school Review of Systems: Denies visual problems or arthralgias Diet is adequate for protein Physical Examination: The patient had patchy alopecia that was most pronounced in the ophiasis distribution and also involved the vertex. The affected areas had miniaturized hair follicles. Hair pull test was positive for 5-6 hairs in catagen and telogen phases. Ears were not low-set. There was an increased distance between the nose and the upper lip, and the philtrum was difficult to appreciate. The patient had retained deciduous teeth, as well as hypodontia and partial anodontia. -

Oral Manifestation of Genodermatoses L

Journal of Medicine, Radiology, Pathology & Surgery (2017), 4, 22–27 NARRATIVE REVIEW Oral manifestation of genodermatoses L. Kavya, S. Vandana, Swetha Paulose, Vishwanath Rangdhol, W. John Baliah, T. Dhanraj Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, Indira Gandhi Institute of Dental Sciences, Pudhucherry, India Keywords Abstract Genodermatoses, mutation, oral Genodermatoses are inherited dermatological disorders associated with the structure manifestation and functions of skin and its appendages. Several genodermatoses presenting with Correspondence multisystem involvement lead to increased morbidity and mortality. Dermatological Dr. L. Kavya, Department of Oral Medicine and diseases, besides including the skin and its supplements may also involve the oral cavity, Radiology, Indira Gandhi Institute of Dental which deserves special attention considering that they may be the only presenting sign Sciences, Pudhucherry, India. of these disorders. The important aspect to be noted about these disorders is the rarity Phone: +91-9442902745. of the conditions and lack of awareness among the population which are the major E-mail: [email protected] drawbacks in the early diagnosis and prompt management of these diseases. This review intends to outline various genodermatoses with their characteristic oral manifestations. Received: 11 April 2017; Accepted: 15 May 2017 doi: 10.15713/ins.jmrps.97 Introduction hence, it is simplified under three classifications based on its distinct features. Genodermatoses or genetic diseases are a group of inherited According to William et al. 2005:[3] skin disorders with a collection of cutaneous and systemic signs 1. Chromosomal and symptoms. In the oral cavity, a wide spectrum of diseases 2. Single gene occurs due to genetic modifications ranging from developmental 3.