Arxiv:1707.00609V2 [Quant-Ph] 3 Oct 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arxiv:1607.01025V2

Observables, gravitational dressing, and obstructions to locality and subsystems William Donnelly∗ and Steven B. Giddings† Department of Physics, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106 Quantum field theory – our basic framework for describing all nongravitational physics – conflicts with general relativity: the latter precludes the standard definition of the former’s essential principle of locality, in terms of commuting local observables. We examine this conflict more carefully, by investigating implications of gauge (diffeomorphism) invariance for observables in gravity. We prove a dressing theorem, showing that any operator with nonzero Poincar´echarges, and in particular any compactly supported operator, in flat-spacetime quantum field theory must be gravitationally dressed once coupled to gravity, i.e. it must depend on the metric at arbitrarily long distances, and we put lower bounds on this nonlocal dependence. This departure from standard locality occurs in the most severe way possible: in perturbation theory about flat spacetime, at leading order in Newton’s constant. The physical observables in a gravitational theory therefore do not organize themselves into local commuting subalgebras: the principle of locality must apparently be reformulated or abandoned, and in fact we lack a clear definition of the coarser and more basic notion of a quantum subsystem of the Universe. We discuss relational approaches to locality based on diffeomorphism-invariant nonlocal operators, and reinforce arguments that any such locality is state-dependent and approximate. We also find limitations to the utility of bilocal diffeomorphism- invariant operators that are considered in cosmological contexts. An appendix provides a concise review of the canonical covariant formalism for gravity, instrumental in the discussion of Poincar´e charges and their associated long-range fields. -

![Arxiv:0908.1787V1 [Quant-Ph] 13 Aug 2009 Ematical Underpinning](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7319/arxiv-0908-1787v1-quant-ph-13-aug-2009-ematical-underpinning-277319.webp)

Arxiv:0908.1787V1 [Quant-Ph] 13 Aug 2009 Ematical Underpinning

August 13, 2009 18:17 Contemporary Physics QuantumPicturalismFinal Contemporary Physics Vol. 00, No. 00, February 2009, 1{32 RESEARCH ARTICLE Quantum picturalism Bob Coecke∗ Oxford University Computing Laboratory, Wolfson Building, Parks Road, OX1 3QD Oxford, UK (Received 01 02 2009; final version received XX YY ZZZZ) Why did it take us 50 years since the birth of the quantum mechanical formalism to discover that unknown quantum states cannot be cloned? Yet, the proof of the `no-cloning theorem' is easy, and its consequences and potential for applications are immense. Similarly, why did it take us 60 years to discover the conceptually intriguing and easily derivable physical phenomenon of `quantum teleportation'? We claim that the quantum mechanical formalism doesn't support our intuition, nor does it elucidate the key concepts that govern the behaviour of the entities that are subject to the laws of quantum physics. The arrays of complex numbers are kin to the arrays of 0s and 1s of the early days of computer programming practice. Using a technical term from computer science, the quantum mechanical formalism is `low-level'. In this review we present steps towards a diagrammatic `high-level' alternative for the Hilbert space formalism, one which appeals to our intuition. The diagrammatic language as it currently stands allows for intuitive reasoning about interacting quantum systems, and trivialises many otherwise involved and tedious computations. It clearly exposes limitations such as the no-cloning theorem, and phenomena such as quantum teleportation. As a logic, it supports `automation': it enables a (classical) computer to reason about interacting quantum systems, prove theorems, and design protocols. -

A Non-Technical Explanation of the Bell Inequality Eliminated by EPR Analysis Eliminated by Bell A

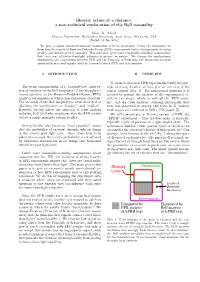

Ghostly action at a distance: a non-technical explanation of the Bell inequality Mark G. Alford Physics Department, Washington University, Saint Louis, MO 63130, USA (Dated: 16 Jan 2016) We give a simple non-mathematical explanation of Bell's inequality. Using the inequality, we show how the results of Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) experiments violate the principle of strong locality, also known as local causality. This indicates, given some reasonable-sounding assumptions, that some sort of faster-than-light influence is present in nature. We discuss the implications, emphasizing the relationship between EPR and the Principle of Relativity, the distinction between causal influences and signals, and the tension between EPR and determinism. I. INTRODUCTION II. OVERVIEW To make it clear how EPR experiments falsify the prin- The recent announcement of a \loophole-free" observa- ciple of strong locality, we now give an overview of the tion of violation of the Bell inequality [1] has brought re- logical context (Fig. 1). For pedagogical purposes it is newed attention to the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) natural to present the analysis of the experimental re- family of experiments in which such violation is observed. sults in two stages, which we will call the \EPR analy- The violation of the Bell inequality is often described as sis", and the \Bell analysis" although historically they falsifying the combination of \locality" and \realism". were not presented in exactly this form [4, 5]; indeed, However, we will follow the approach of other authors both stages are combined in Bell's 1976 paper [2]. including Bell [2{4] who emphasize that the EPR results We will concentrate on Bohm's variant of EPR, the violate a single principle, strong locality. -

Dynamical Relaxation to Quantum Equilibrium

Dynamical relaxation to quantum equilibrium Or, an account of Mike's attempt to write an entirely new computer code that doesn't do quantum Monte Carlo for the first time in years. ESDG, 10th February 2010 Mike Towler TCM Group, Cavendish Laboratory, University of Cambridge www.tcm.phy.cam.ac.uk/∼mdt26 and www.vallico.net/tti/tti.html [email protected] { Typeset by FoilTEX { 1 What I talked about a month ago (`Exchange, antisymmetry and Pauli repulsion', ESDG Jan 13th 2010) I showed that (1) the assumption that fermions are point particles with a continuous objective existence, and (2) the equations of non-relativistic QM, allow us to deduce: • ..that a mathematically well-defined ‘fifth force', non-local in character, appears to act on the particles and causes their trajectories to differ from the classical ones. • ..that this force appears to have its origin in an objectively-existing `wave field’ mathematically represented by the usual QM wave function. • ..that indistinguishability arguments are invalid under these assumptions; rather antisymmetrization implies the introduction of forces between particles. • ..the nature of spin. • ..that the action of the force prevents two fermions from coming into close proximity when `their spins are the same', and that in general, this mechanism prevents fermions from occupying the same quantum state. This is a readily understandable causal explanation for the Exclusion principle and for its otherwise inexplicable consequences such as `degeneracy pressure' in a white dwarf star. Furthermore, if assume antisymmetry of wave field not fundamental but develops naturally over the course of time, then can see character of reason for fermionic wave functions having symmetry behaviour they do. -

Infinite Potential Show Title: Generic Show Episode #101 Date: 3/17/20 Transcribed by Daily Transcription Tre

INFINITE POTENTIAL SHOW TITLE: GENERIC SHOW EPISODE #101 DATE: 3/17/20 TRANSCRIBED BY DAILY TRANSCRIPTION_TRE 00:00:28 DAVID BOHM People talked about the world, and I said, "Where does it end?" and, uh, uh... MALE And what answer did they give? DAVID BOHM Well, they-I never, uh, I don't remember. It wasn't terribly convincing I suppose. [LAUGH] DR. DAVID C. It was, uh, a night, and we were SCHRUM walking under the stars, black sky, and he looked up to the stars, and he said, "Ordinarily, when we look to the sky and look to the stars, we think of stars as objects far out and vast spaces between them." He said, "There's another way we can look at it. We can look at the vacuum at the emptiness instead as a planum, as infinitely full rather than infinitely empty. And that the material objects themselves are like little bubbles, little vacancies in this vast sea." 00:01:25 DR. DAVID C. So David Bohm, in a sense, was SCHRUM using that view to have me look at the stars and to have a sense of the night sky all of a sudden in a different way, as one whole living organism and these little bits that we call matter as sort to just little holes in it. DR. DAVID C. He often mentioned just one other SCHRUM aspect of this, that this planum, in a cubic centimeter of the planum, there's more, uh, energy matter than in the entire visible Page 2 of 62 universe. -

Pilot-Wave Theory, Bohmian Metaphysics, and the Foundations of Quantum Mechanics Lecture 8 Bohmian Metaphysics: the Implicate Order and Other Arcana

Pilot-wave theory, Bohmian metaphysics, and the foundations of quantum mechanics Lecture 8 Bohmian metaphysics: the implicate order and other arcana Mike Towler TCM Group, Cavendish Laboratory, University of Cambridge www.tcm.phy.cam.ac.uk/∼mdt26 and www.vallico.net/tti/tti.html [email protected] – Typeset by FoilTEX – 1 Acknowledgements The material in this lecture is largely derived from books and articles by David Bohm, Basil Hiley, Paavo Pylkk¨annen, F. David Peat, Marcello Guarini, Jack Sarfatti, Lee Nichol, Andrew Whitaker, and Constantine Pagonis. The text of an interview between Simeon Alev and Peat is extensively quoted. Other sources used and many other interesting papers are listed on the course web page: www.tcm.phy.cam.ac.uk/∼mdt26/pilot waves.html MDT – Typeset by FoilTEX – 2 More philosophical preliminaries Positivism: Observed phenomena are all that require discussion or scientific analysis; consideration of other questions, such as what the underlying mechanism may be, or what ‘real entities’ produce the phenomena, is dismissed as meaningless. Truth begins in sense experience, but does not end there. Positivism fails to prove that there are not abstract ideas, laws, and principles, beyond particular observable facts and relationships and necessary principles, or that we cannot know them. Nor does it prove that material and corporeal things constitute the whole order of existing beings, and that our knowledge is limited to them. Positivism ignores all humanly significant and interesting problems, citing its refusal to engage in reflection; it gives to a particular methodology an absolutist status and can do this only because it has partly forgotten, partly repressed its knowledge of the roots of this methodology in human concerns. -

Non-Locality in the Stochastic Interpretation of the Quantum Theory Annales De L’I

ANNALES DE L’I. H. P., SECTION A D. BOHM Non-locality in the stochastic interpretation of the quantum theory Annales de l’I. H. P., section A, tome 49, no 3 (1988), p. 287-296 <http://www.numdam.org/item?id=AIHPA_1988__49_3_287_0> © Gauthier-Villars, 1988, tous droits réservés. L’accès aux archives de la revue « Annales de l’I. H. P., section A » implique l’accord avec les conditions générales d’utilisation (http://www.numdam. org/conditions). Toute utilisation commerciale ou impression systématique est constitutive d’une infraction pénale. Toute copie ou impression de ce fichier doit contenir la présente mention de copyright. Article numérisé dans le cadre du programme Numérisation de documents anciens mathématiques http://www.numdam.org/ Ann. Inst. Henri Poincare, Vol. 49, n° 3, 1988, 287 Physique theorique Non-Locality in the Stochastic Interpretation of the Quantum Theory D. BOHM Department of Physics, Birkbeck College (London University), Malet Street, London WC1E 7HX ABSTRACT. - This article reviews the stochastic interpretation of the quantum theory and shows in detail how it implies non-locality. RESUME . - Cet article presente une revue de 1’interpretation stochas- tique de la theorie quantique et montre en detail en quoi elle implique une non-localite. 1. INTRODUCTION It gives me great pleasure on the occasion of Jean-Pierre Vigier’s retire- ment to recall our long period of fruitful association and to say something about the stochastic interpretation of the quantum theory, in which we worked together in earlier days. Because of requirements of space, however, this article will be a condensation of my talk (*) which was in fact based on a much more extended article by Basil Hiley and me [1 ]. -

I Speculative Physics: the Ontology of Theory And

Speculative Physics: the Ontology of Theory and Experiment in High Energy Particle Physics and Science Fiction by Clarissa Ai Ling Lee Graduate Program in Literature Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ___________________________ N. Katherine Hayles, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Mark C. Kruse, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Mark B. Hansen ___________________________ Andrew Janiak ___________________________ Timothy Lenoir Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Program in Literature in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 i v ABSTRACT Speculative Physics: the Ontology of Theory and Experiment in High Energy Particle Physics and Science Fiction by Clarissa Ai Ling Lee Graduate Program in Literature Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ N. Katherine Hayles, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Mark C. Kruse, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Mark B. Hansen ___________________________ Andrew Janiak ___________________________ Timothy Lenoir An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Program in Literature in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 i v Copyright by Clarissa Ai Ling Lee 2014 Abstract The dissertation brings together approaches across the fields of physics, critical theory, literary studies, philosophy of physics, sociology of science, and history of science to synthesize a hybrid approach for instigating more rigorous and intense cross- disciplinary interrogations between the sciences and the humanities. I explore the concept of speculation in particle physics and science fiction to examine emergent critical approaches for working in the two areas of literature and physics (the latter through critical science studies), but with the expectation of contributing new insights to media theory, critical code studies, and also the science studies of science fiction. -

16-1 Paul Howard

BESHARA MAGAZINE Unity in the Contemporary World ISSUE 16-1 · SUMMER 2020 INFINITE POTENTIAL: THE LIFE & IDEAS OF DAVID BOHM Film director Paul Howard talks about his new film on a remarkable scientist whose vision of wholeness and interconnectivity is now reaching a wide audience A still from the film Infinite Potential: The Life & Ideas of David Bohm avid Bohm ( 191 7–92 ) has been descri - Ear lier this year, we published an interview Dbed as one of the most significant thin- we did with him in 1991 . Now a film has been kers of the twentieth century. As a theoretical made about his life and ideas which brings to - physicist, he developed a radical approach to gether an impressive array of contemporary quantum mechanics which proposes that thinkers who are taking his vision forward. whole ness and interconnectivity are the fun - Paul Howard, its director, talks to Jane Clark damental principles of reality. In line with and Michael Cohen about the making of the this, his interests and influence extended be - film and Bohm’s importance for the world yond the confines of science to the realms of today. philosophy, spirituality and social change. u nfinite Potential begins with a story by Bohm’s one-time Istudent Dr David Schrum: “It was a night and we were walking under the stars, a black sky. David looked up at the stars and said: ‘Ordinarily, when we look to the sky and we look at the stars, we think of the stars as objects far out and that they have space in between them. -

Key Points for Understanding of Unruh and Hawking Effects

Key points for understanding of Unruh and Hawking effects Peter Slavov∗ Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski”, Theoretical Physics Department, August 25, 2021 Abstract The present paper stress on the distinction between the two idealizations – eternal (pri- mordial) black hole and a black hole formed in a process of gravitation collapse. Such a distinction is an essential condition for a better understanding of the relation between Unruh effect and Hawking effect. The fundamental character of the discussions inside requires a preferred orientation to results of the local QFT in curved space-time. 1 Introduction The meeting between the quantum physics and a space-time horizon is one of the most untrivial things in the physics. A serious challenge to common sense, a test about how we understand the basic physical concepts and notions like space-time, causality, locality, dynamics, evolution, quantization, temperature, information, entropy, energy, mass, particle. In early years of General Relativity (GR) black hole (BH) has been an exotic feature of causality structure of the space-time. After obtaining Kerr’s solution of Einstein–Hilbert’s equations in 1963, the development of BH physics starts growing up as a separate discipline in gravitational science fruitful for many new results. The Golden Age of this area of research was a highest pilotage in theoretical and mathematical physics. It consist of a few number of important theorems coming after a deep study of gravity solutions with symmetries and also of a brilliant (skillfully) defined system of basic notions leading to outstanding physical results (4 lows of BH mechanics [BCH1973] and Smarr’s formula [S1973]) despite (regardless of) the difficulties in the physical interpretation and the conflict with common sense. -

Basil Hiley Basil Was Born in Yangon, Myanmar, (Formerly Known As Burma) on the 15 November 1935

What does it mean to comprehend and to participate in life holistically? Pari Dialogues 2019 explores this challenge. Through seminars, discussions and practical sessions, we will journey together into subtle realms of art, physics, cultural studies, philosophy, economics and technology—pathways to investigate wholeness and to ponder our place in it. Join us at The Pari Center and engage in a spirit that honours the approaches and work of David Bohm and F. David Peat, as we explore bringing together art, science and the sacred in the quest for wholeness. This will be an informal meeting with presentations by experts followed by roundtable dis- cussions. The cost of the event is 1400 euros. The event fee includes 6 night stay in pri- vate accommodation and all meals. It also includes activities, materials and teaching ses- sions. The event starts on Thursday August 29 at 19:00 with dinner and ends on Wednes- day September 4 after lunch. Jena Axelrod Jena joined Ideal Prediction as Director of Sales in 2018 bringing 20 years of experience in launching innovative financial market offerings from the first electronic treasury trading system, LibertyDirect, to the first centrally-cleared FX market, FXMarketSpace. Jena directed and produced the upcoming documentary Absurdity of Certainty on the rise of certainty in the Western worldview, based on the life and ideas of Dr. F. David Peat. Jena has served on the Board of The Pari Center since 2016. Absurdity of Certainty Why are we certain in a chaotic world? The upcoming documentary Absurdity of Certainty explores the illusion of control and certainty in historical scientific context with quantum physicist turned philosopher Dr. -

Article (Published Version)

Article All quantum states useful for teleportation are nonlocal resources CAVALCANTI, Daniel, et al. Abstract Understanding the relation between the different forms of inseparability in quantum mechanics is a longstanding problem in the foundations of quantum theory and has implications for quantum information processing. Here we make progress in this direction by establishing a direct link between quantum teleportation and Bell nonlocality. In particular, we show that all entangled states which are useful for teleportation are nonlocal resources, i.e., lead to deterministic violation of Bell's inequality. Our result also extends the phenomenon of superactivation of quantum nonlocality, recently proven by C. Palazuelos [Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 190401 (2012)], and suggests that the latter might in fact be more general than initially thought. Reference CAVALCANTI, Daniel, et al. All quantum states useful for teleportation are nonlocal resources. Physical Review. A, 2013, vol. 87, no. 4 DOI : 10.1103/PhysRevA.87.042104 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:36420 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 PHYSICAL REVIEW A 87, 042104 (2013) All quantum states useful for teleportation are nonlocal resources Daniel Cavalcanti,1 Antonio Ac´ın,2,3 Nicolas Brunner,4,5 and Tamas´ Vertesi´ 6 1Centre for Quantum Technologies, University of Singapore, 117542, Singapore 2Institut de Ciencies Fotoniques, 08860 Castelldefels (Barcelona), Spain 3Institucio´ Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avanc¸ats, Lluis Companys 23, 08010 Barcelona, Spain 4H. H. Wills Physics Laboratory, University of Bristol, Tyndall Avenue, Bristol BS8 1TL, United Kingdom 5Departement´ de Physique Theorique,´ Universite´ de Geneve,` 1211 Geneve,` Switzerland 6Institute for Nuclear Research, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, P.O.