Assessing the Cumulative Effects of Linear Recreation Routes on Wildlife Habitats on the Okanogan and Wenatchee National Forests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Areas of the National Forest System, As of September 30, 2019

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2019 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2019 Metric Equivalents When you know: Multiply by: To fnd: Inches (in) 2.54 Centimeters Feet (ft) 0.305 Meters Miles (mi) 1.609 Kilometers Acres (ac) 0.405 Hectares Square feet (ft2) 0.0929 Square meters Yards (yd) 0.914 Meters Square miles (mi2) 2.59 Square kilometers Pounds (lb) 0.454 Kilograms United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System November 2019 As of September 30, 2019 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, DC 20250-0003 Website: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover Photo: Mt. Hood, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon Courtesy of: Susan Ruzicka USDA Forest Service WO Lands and Realty Management Statistics are current as of: 10/17/2019 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 192,994,068 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 503 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service administers 149 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 456 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. The Forest Service also administers several other types of nationally designated -

Backcountry Campsites at Waptus Lake, Alpine Lakes Wilderness

BACKCOUNTRY CAMPSITES AT WAPTUS LAKE, ALPINE LAKES WILDERNESS, WASHINGTON: CHANGES IN SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION, IMPACTED AREAS, AND USE OVER TIME ___________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty Central Washington University ___________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Resource Management ___________________________________________________ by Darcy Lynn Batura May 2011 CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Graduate Studies We hereby approve the thesis of Darcy Lynn Batura Candidate for the degree of Master of Science APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY ______________ _________________________________________ Dr. Karl Lillquist, Committee Chair ______________ _________________________________________ Dr. Anthony Gabriel ______________ _________________________________________ Dr. Thomas Cottrell ______________ _________________________________________ Resource Management Program Director ______________ _________________________________________ Dean of Graduate Studies ii ABSTRACT BACKCOUNTRY CAMPSITES AT WAPTUS LAKE, ALPINE LAKES WILDERNESS, WASHINGTON: CHANGES IN SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION, IMPACTED AREAS, AND USE OVER TIME by Darcy Lynn Batura May 2011 The Wilderness Act was created to protect backcountry resources, however; the cumulative effects of recreational impacts are adversely affecting the biophysical resource elements. Waptus Lake is located in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness, the most heavily used wilderness in Washington -

Interior Columbia Basin Mollusk Species of Special Concern

Deixis l-4 consultants INTERIOR COLUMl3lA BASIN MOLLUSK SPECIES OF SPECIAL CONCERN cryptomasfix magnidenfata (Pilsbly, 1940), x7.5 FINAL REPORT Contract #43-OEOO-4-9112 Prepared for: INTERIOR COLUMBIA BASIN ECOSYSTEM MANAGEMENT PROJECT 112 East Poplar Street Walla Walla, WA 99362 TERRENCE J. FREST EDWARD J. JOHANNES January 15, 1995 2517 NE 65th Street Seattle, WA 98115-7125 ‘(206) 527-6764 INTERIOR COLUMBIA BASIN MOLLUSK SPECIES OF SPECIAL CONCERN Terrence J. Frest & Edward J. Johannes Deixis Consultants 2517 NE 65th Street Seattle, WA 98115-7125 (206) 527-6764 January 15,1995 i Each shell, each crawling insect holds a rank important in the plan of Him who framed This scale of beings; holds a rank, which lost Would break the chain and leave behind a gap Which Nature’s self wcuid rue. -Stiiiingfieet, quoted in Tryon (1882) The fast word in ignorance is the man who says of an animal or plant: “what good is it?” If the land mechanism as a whole is good, then every part is good, whether we understand it or not. if the biota in the course of eons has built something we like but do not understand, then who but a fool would discard seemingly useless parts? To keep every cog and wheel is the first rule of intelligent tinkering. -Aido Leopold Put the information you have uncovered to beneficial use. -Anonymous: fortune cookie from China Garden restaurant, Seattle, WA in this “business first” society that we have developed (and that we maintain), the promulgators and pragmatic apologists who favor a “single crop” approach, to enable a continuous “harvest” from the natural system that we have decimated in the name of profits, jobs, etc., are fairfy easy to find. -

The Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest Restoration Strategy

United States Department of The Okanogan-Wenatchee National Agriculture Forest Restoration Strategy: a Forest Service process for guiding restoration Pacific Northwest Region projects within the context of ecosystem management DRAFT Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest March 9, 2010 Contents OKANOGAN-WENATCHEE NATIONAL FOREST ECOSYSTEM RESTORATION VISION ..... 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 2 DOCUMENT ORGANIZATION ....................................................................................................................... 3 NEW SCIENCE AND OTHER RELEVANT INFORMATION ................................................................................ 4 PART I: BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................... 8 MANAGEMENT DIRECTION AND POLICY ..................................................................................................... 8 SETTING THE STAGE FOR THE NEXT STEPS - KEY CONCEPTS ..................................................................... 9 Ecosystem Management ........................................................................................................................ 9 Forest Restoration .............................................................................................................................. 10 Aquatic Disturbance .......................................................................................................................... -

The Wild Cascades

THE WILD CASCADES October-November 1969 2 THE WILD CASCADES FARTHEST EAST: CHOPAKA MOUNTAIN Field Notes of an N3C Reconnaissance State of Washington, school lands managed by May 1969 the Department of Natural Resources. The absolute easternmost peak of the North Cascades is Chopaka Mountain, 7882 feet. An This probably is the most spectacular chunk abrupt and impressive 6700-foot scarp drops of alpine terrain owned by the state. Certain from the flowery summit to blue waters of ly its fame will soon spread far beyond the Palmer Lake and meanders of the Similka- Okanogan. Certainly the state should take a mean River, surrounded by green pastures new, close look at Chopaka and develop a re and orchards. Beyond, across this wide vised management plan that takes into account trough of a Pleistocene glacier, roll brown the scenic and recreational resources. hills of the Okanogan Highlands. Northward are distant, snowy beginnings of Canadian ranges. Far south, Tiffany Mountain stands above forested branches of Toats Coulee Our gang became aware of Chopaka on the Creek. Close to the west is the Pasayten Fourth of July weekend of 1968 while explor Wilderness Area, dominated here by Windy ing Horseshoe Basin -- now protected (except Peak, Horseshoe Mountain, Arnold Peak — from Emmet Smith's cattle) within the Pasay the Horseshoe Basin country. Farther west, ten Wilderness Area. We looked east to the hazy-dreamy on the horizon, rise summits of wide-open ridges of Chopaka Mountain and the Chelan Crest and Washington Pass. were intrigued. To get there, drive the Okanogan Valley to On our way to Horseshoe Basin we met Wil Tonasket and turn west to Loomis in the Sin- lis Erwin, one of the Okanoganites chiefly lahekin Valley. -

Studies on the Genus Carex on the Idaho Panhandle National Forests

STUDIES IN THE GENUS CAREX ON THE IDAHO PANHANDLE NATIONAL FORESTS by Steven L. Caicco Natural Heritage Section Nongame Wildlife/Endangered Species Program Bureau of Wildlife December 1988 Idaho Department of Fish and Game 600 South Walnut Street, P.O. Box 25 Boise, Idaho 83707 Jerry M. Conley, Director Cooperative Challenge Grant Project Idaho Panhandle National Forests Idaho Department of Fish and Game Contract No. 53-0281-7-163 ABSTRACT Eleven of thirteen species of the genus Carex (sedges) which have been designated as Sensitive Species within Region 1 of the U.S. Forest Service are known to occur in Idaho. In this study, the status of these thirteen species, plus one other species of sedge, on the Idaho Panhandle National Forests was investigated through herbaria searches and field surveys. In individual reports, the taxonomy, description, range, habitat, collection record, and conservation status of nine of the fourteen species are discussed. Each species discussion ends with recommendations for land managers and field personnel. The other five species of sedge are more briefly discussed. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT...................................................... i TABLE OF CONTENTS............................................. ii LIST OF APPENDICES............................................ ii INTRODUCTION.................................................. 1 INDIVIDUAL SPECIES REPORTS Carex aenea Fern. ............................................ 2 Carex buxbaumii Wahl. ........................................ 4 Carex californica -

Northeast Chapter Volunteer Hours Report for Year 2013-2014

BACK COUNTRY HORSEMEN OF WASHINGTON - Northeast Chapter Volunteer Hours Report for Year 2013-2014 Work Hours Other Hours Travel Equines Volunteer Name Project Agency District Basic Skilled LNT Admin Travel Vehicle Quant Days Description of work/ trail/trail head names Date Code Code Hours Hours Educ. Pub. Meet Time Miles Stock Used AGENCY & DISTRICT CODES Agency Code Agency Name District Codes for Agency A Cont'd A U.S.F.S. District Code District Name B State DNR OKNF Okanogan National Forest C State Parks and Highways Pasayten Wilderness D National Parks Lake Chelan-Sawtooth Wilderness E Education and LNT WNF Wenatchee National Forest F Dept. of Fish and Wildlife (State) Alpine Lakes Wilderness G Other Henry M Jackson Wilderness M Bureau of Land Management William O Douglas Wilderness T Private or Timber OLNF Olympic National Forest W County Mt Skokomish Wilderness Wonder Mt Wilderness District Codes for U.S.F.S. Agency Code A Colonel Bob Wilderness The Brothers Wilderness District Code District Name Buckhorn Wilderness CNF Colville National Forest UMNF Umatilla National Forest Salmo-Priest Wilderness Wenaha Tucannon Wilderness GPNF Gifford Pinchot National Forest IDNF Idaho Priest National Forest Goat Rocks Wilderness ORNF Oregon Forest Mt Adams Wilderness Indian Heaven Wilderness Trapper Wilderness District Codes for DNR Agency B Tatoosh Wilderness MBS Mt Baker Snoqualmie National Forest SPS South Puget Sound Region Glacier Peak Wilderness PCR Pacific Cascade Region Bolder River Wilderness OLR Olympic Region Clear Water Wilderness NWR Northwest Region Norse Peak Mt Baker Wilderness NER Northeast Region William O Douglas Wilderness SER Southeast Region Glacier View Wilderness Boulder River Wilderness VOLUNTEER HOURS GUIDELINES Volunteer Name 1. -

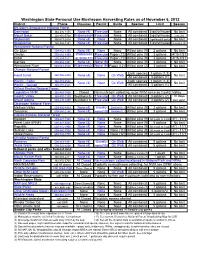

Washington State Personal Use Mushroom Harvesting Rules As of November 6, 2012 District Phone Closures Permit Guide Species Limit Season Mt

Washington State Personal Use Mushroom Harvesting Rules as of November 6, 2012 District Phone Closures Permit Guide Species Limit Season Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest Darrington 360-436-1155 None (4) Free use None All combined 5 gal/yr/house No limit Mount Baker 360-856-5700 Wilderness(4) Free use None All combined 5 gal/yr/house 2 weeks Skykomish 360-677-2414 None (4) None None All combined 1 gal/day&5 gal/yr No limit Snoqualmie 425-888-1421 None (4) Free use None All combined 5 gal/yr/house 2 weeks (8) Wenatchee National Forest Cle Elum 509-852-1100 None (4) None None All but pine (9) 2 gallons No limit Chelan 509-682-4900 Wilderness Free use Paper (12) All but pine (9) 3 gallons 4/15-7/31 Entiat 509-784-1511 &LSR(4,11) Free use Paper (12) All but pine (9) 3 gallons 4/15-7/31 Naches 509-653-1401 None (4) None (9) None All but pine (9) 3 gallons No limit Wenatchee River 509-548-2550 Wilderness(4) None (9) Paper (12) All but pine (2) 3 gallons No limit Olympic National Forest Each species 1 gallon (1,3) Hood Canal 360-765-2200 None (4) None On Web No limit All combined 3 gallons (1) Pacific - Forks 360-374-6522 Each species 1 gallon (1,3) None (4) None On Web No limit Pacific - Quinalt 360-288-2525 All combined 3 gallons (1) Gifford Pinchot National Forest Legislative NVM 360-449-7800 Closed No mushroom collecting, outer NVM same as Cowlitz Valley Cowlitz Valley 360-497-1100 SeeMap(4,5) Free use On Web All combined 3 gallons (2) 10 days Mount Adams 509-395-3400 SeeMap(4,5) Free use On Web All combined 3 gallons (2) per year Okanogan -

April 2016 Report

Editor’s Note: Recreation Reports are printed every other week. April 26, 2016 Its spring, which means nice weather, wildflowers, bugs, fast flowing rivers and streams, and opening of national forest campgrounds. There are 137 highly developed campgrounds, six horse camps and 16 group sites available for use in the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest. Opening these sites after the long winter season requires a bit more effort than just unlocking a gate. Before a campground can officially open for use the following steps need to occur: 1. Snow must be gone and campground roads need to be dry. 2. Hazard tree assessments occur. Over the winter trees may have fallen or may be leaning into other trees, or broken branches may be hanging up in limbs above camp spots. These hazards must be removed before it is safe for campers to use the campground. 3. Spring maintenance must occur. Crews have to fix anything that is broken or needs repair. That includes maintenance and repair work on gates, bathrooms/outhouses, picnic tables, barriers that need to be replaced or fixed, shelters, bulletin boards, etc. 4. Water systems need to be tested and repairs made, also water samples are sent to county health departments to be tested to ensure the water is safe for drinking. 5. Garbage dumpsters have to be delivered. 6. Once dumpsters are delivered, garbage that had been left/dumped in campgrounds over the winter needs to be removed. 7. Vault toilets have to be pumped out by a septic company. 8. Outhouses need to be cleaned and sanitized and supplies restocked. -

Public Law 94-527 94Th Congress an Act to Amend the National Trails System Act (82 Stat

PUBLIC LAW 94-527—OCT. 17, 1976 90 STAT. 2481 Public Law 94-527 94th Congress An Act To amend the National Trails System Act (82 Stat. 919), and for other purposes. Oct. 17, 1976 [S. 2112] Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the National National scenic Trails System Act (82 Stat. 919; 16 U.S.C. 1241 et seq.) is amended trails, as follows: In section 5(c), add the following new paragraphs; 16 USC 1244. "(15) Bartram Trail, extending through the States of Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mis sissippi, and Tennessee. "(16) Daniel Boone Trail, extending from the vicinity of States- ville. North Carolina, to Fort Boonesborough State Park, Kentucky. "(17) Desert Trail, extending from the Canadian border through parts of Idaho, Washington, Oregon, Nevada, California, and Ari zona, to the Mexican border. "(18) Dominguez-Escalante Trail, extending approximately two thousand miles along the route of the 1776 expedition led by Father Francisco Atanasio Dominguez and Father Silvestre Velez de Escalante, originating in Santa Fe, New Mexico; proceeding north west along the San Juan, Dolores, Gunnison, and White Rivers in Colorado; thence westerly to Utah Lake; thence southward to Arizona and returning to Santa Fe. "(19) Florida Trail, extending north from Everglades National Park, including the Big Cypress Swamp, the Kissimme Prairie, the Withlacoochee State Forest, Ocala National Forest, Osceola National Forest, and Black Water River State Forest, said completed trail to be approximately one thousand three hundred miles long, of which over four hundred miles of trail have already been built. -

Summary of Public Comment, Appendix B

Summary of Public Comment on Roadless Area Conservation Appendix B Requests for Inclusion or Exemption of Specific Areas Table B-1. Requested Inclusions Under the Proposed Rulemaking. Region 1 Northern NATIONAL FOREST OR AREA STATE GRASSLAND The state of Idaho Multiple ID (Individual, Boise, ID - #6033.10200) Roadless areas in Idaho Multiple ID (Individual, Olga, WA - #16638.10110) Inventoried and uninventoried roadless areas (including those Multiple ID, MT encompassed in the Northern Rockies Ecosystem Protection Act) (Individual, Bemidji, MN - #7964.64351) Roadless areas in Montana Multiple MT (Individual, Olga, WA - #16638.10110) Pioneer Scenic Byway in southwest Montana Beaverhead MT (Individual, Butte, MT - #50515.64351) West Big Hole area Beaverhead MT (Individual, Minneapolis, MN - #2892.83000) Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness, along the Selway River, and the Beaverhead-Deerlodge, MT Anaconda-Pintler Wilderness, at Johnson lake, the Pioneer Bitterroot Mountains in the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest and the Great Bear Wilderness (Individual, Missoula, MT - #16940.90200) CLEARWATER NATIONAL FOREST: NORTH FORK Bighorn, Clearwater, Idaho ID, MT, COUNTRY- Panhandle, Lolo WY MALLARD-LARKINS--1300 (also on the Idaho Panhandle National Forest)….encompasses most of the high country between the St. Joe and North Fork Clearwater Rivers….a low elevation section of the North Fork Clearwater….Logging sales (Lower Salmon and Dworshak Blowdown) …a potential wild and scenic river section of the North Fork... THE GREAT BURN--1301 (or Hoodoo also on the Lolo National Forest) … harbors the incomparable Kelly Creek and includes its confluence with Cayuse Creek. This area forms a major headwaters for the North Fork of the Clearwater. …Fish Lake… the Jap, Siam, Goose and Shell Creek drainages WEITAS CREEK--1306 (Bighorn-Weitas)…Weitas Creek…North Fork Clearwater. -

Idaho Panhandle National Forest: Sandpoint, Bonners Ferry and Priest Lake Ranger Districts

IDAHO PANHANDLE NA TJONAL FORESTS Sandpoint, Bonners Ferry, and Priest Lake Ranger Districts Order No. F-II-002 Occupancy and Use Restrictions Pursuant to 36 CFR 261.50(a), the following acts are prohibited in the area displayed on the attached map that covers National Forest lands on the Kaniksu National Forest north of the Clark Fork River, Lake Pend Oreille, and the Pend Oreille River. This order applies to all National Forest system lands and facilities located and/or permitted on lands described above. 1. It is prohibited to possess or store any foodl (humanfood or animalfood, including petfood) or refuse EXCEPT as specified in this order from April 1 to December 1, annually (36 CFR 261.58(cc». 2. It is prohibited to possess, store, or transport any bird, fish, or other animal, or parts thereof EXCEPT as specified in the order from April 1 to December 1, annually (36 CFR 261.58(s». UNDER THIS ORDER IT IS REQUIRED THAT: In Areas Mapped as Front Country: 1. Human, pet, and livestock food (except baled or cubed hay without additives), garbage, and all other attractants (cookware/utensils, personal hygiene products) shall be stored within buildings (buildings that are secure from wildlife entry), hard sided vehicles, or within approved bear-resistant storage containers (coolers are NOT bear-resistant), or other acceptably stored methods at all times (night and day) unless being prepared for eating, being consumed (eaten/drank), being transported, or being prepared for acceptable storage. See Attachment 'A' for definitions. 2. Attractants (e.g.food leftovers, bacon grease, animal entrails) shall not be buried, discarded, or burned in an open campfire in areas defined as Front Country on the attached map.