Ethiopia: a Priority Country for Universal Access to WASH in Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oromia Region Administrative Map(As of 27 March 2013)

ETHIOPIA: Oromia Region Administrative Map (as of 27 March 2013) Amhara Gundo Meskel ! Amuru Dera Kelo ! Agemsa BENISHANGUL ! Jangir Ibantu ! ! Filikilik Hidabu GUMUZ Kiremu ! ! Wara AMHARA Haro ! Obera Jarte Gosha Dire ! ! Abote ! Tsiyon Jars!o ! Ejere Limu Ayana ! Kiremu Alibo ! Jardega Hose Tulu Miki Haro ! ! Kokofe Ababo Mana Mendi ! Gebre ! Gida ! Guracha ! ! Degem AFAR ! Gelila SomHbo oro Abay ! ! Sibu Kiltu Kewo Kere ! Biriti Degem DIRE DAWA Ayana ! ! Fiche Benguwa Chomen Dobi Abuna Ali ! K! ara ! Kuyu Debre Tsige ! Toba Guduru Dedu ! Doro ! ! Achane G/Be!ret Minare Debre ! Mendida Shambu Daleti ! Libanos Weberi Abe Chulute! Jemo ! Abichuna Kombolcha West Limu Hor!o ! Meta Yaya Gota Dongoro Kombolcha Ginde Kachisi Lefo ! Muke Turi Melka Chinaksen ! Gne'a ! N!ejo Fincha!-a Kembolcha R!obi ! Adda Gulele Rafu Jarso ! ! ! Wuchale ! Nopa ! Beret Mekoda Muger ! ! Wellega Nejo ! Goro Kulubi ! ! Funyan Debeka Boji Shikute Berga Jida ! Kombolcha Kober Guto Guduru ! !Duber Water Kersa Haro Jarso ! ! Debra ! ! Bira Gudetu ! Bila Seyo Chobi Kembibit Gutu Che!lenko ! ! Welenkombi Gorfo ! ! Begi Jarso Dirmeji Gida Bila Jimma ! Ketket Mulo ! Kersa Maya Bila Gola ! ! ! Sheno ! Kobo Alem Kondole ! ! Bicho ! Deder Gursum Muklemi Hena Sibu ! Chancho Wenoda ! Mieso Doba Kurfa Maya Beg!i Deboko ! Rare Mida ! Goja Shino Inchini Sululta Aleltu Babile Jimma Mulo ! Meta Guliso Golo Sire Hunde! Deder Chele ! Tobi Lalo ! Mekenejo Bitile ! Kegn Aleltu ! Tulo ! Harawacha ! ! ! ! Rob G! obu Genete ! Ifata Jeldu Lafto Girawa ! Gawo Inango ! Sendafa Mieso Hirna -

14 3W Food123017 A4.Pdf (English)

Ethiopia: 3W - Food Cluster Ongoing and Planned Activities map (as of December 2017) ERITREA Tahtay Adiyabo REST Total Number of Partners Laelay DPPB 8 DPPB Erob Dalul REST REST Adiyabo Gulomekeda DPPB Medebay REST DPPB Zana DPPB Red Sea Asgede DPPB DPPB Werei DPPB Hawzen Tsimbila DPPB Leke Koneba REST REST DPPB DPPB TIGRAY DPPB DPPB DPPB REST REST Berahile Kola DPPB DPPB REST Kelete SUDAN Temben Tselemti Awelallo DPPB DPPB Afdera DPPB DPPB Tselemt Ab Ala DPPB DPPB REST REST DPPB Erebti DPPB Abergele Hintalo Saharti DPPB DPPB Bidu Wejirat DPPB DPPB SCI SCI Samre Gulf of DPPB DPPB DPPB Dabat Megale Aden Janamora Alaje Wegera Sahla SCI Raya FHE DPPB DPPB Azebo DPPB Teru Gonder East Ziquala Ofla REST Kurri Zuria DPPB Belesa Sekota DPPB DPPB DPPB Dehana Yalo DPPB DPPB FHE DPPB AMHARA FHE Alamata DPPB Ebenat Gaz Gulina FHE Kobo DPPB Gibla DPPB Elidar DPPB Bugna SCI FHE DPPB Awra AFAR SCI Lasta Gidan DPPB Lay Guba Meket Lafto Gayint SCI Ewa DPPB FHE DPPB FHE Tach Ambasel SCI Aysaita Gayint Wadla DPPB Habru Dubti DPPB FHE Chifra Mile DPPB Delanta DPPB DPPB DPPB DPPB DPPB DPPB FHE Mekdela DPPB Adaa'r DPPB DPPB DPPB Simada DPPB Kutaber DPPB Afambo DJIBOUTI Sayint Bati Tenta DPPB DPPB Telalak DPPB DPPB DPPB DPPB Were Ilu Enarj Argoba DPPB DPPB DPPB Enawga Legehida DPPB Gewane Ayisha DPPB Albuko Dewe DPPB Debresina DPPB DPPB DPPB DPPB Wegde DPPB Artuma DPPB BENISHANGUL DPPB DPPB Debay DPPB Fursi DPPB Kelela DPPB GUMUZ Telatgen DPPB DPPB Jama DPPB DPPB Amuru Dera DPPB DPPB Afdem Erer SOMALI DPPB Menz Mama Jille Hadelela Shinile DPPB DPPB Dembel DPPB -

Ethiopia: 3W - Health Cluster Ongoing Activities Map (December 2016)

Ethiopia: 3W - Health Cluster Ongoing Activities map (December 2016) ERITREA 8 Total Number of Partners Ahferom CCM CCM GOAL GOAL Erob CCM Adwa GOAL Red Sea GOAL Werei CCM Leke GOAL Koneba GOAL Hawzen GOAL CCM SUDAN TIGRAY GOAL Ab Ala GOAL AMHARA Megale Gulf of GOAL Aden DCA IMC Kobo AFAR Lay DCA Meket DCA Gayint IMC IMC Tach Gayint DCA Guba Lafto GOAL BENESHANGUL Dera IMC Worebabu Simada GOAL GOAL GOAL GOAL GUMU IMC Thehulederie Sirba DJIBOUTI Abay Telalak Afambo GOAL GOAL IRC Tenta GOAL Sayint GOAL GOAL IRC GOAL GOAL Were Ilu Ayisha IRC IRC GOAL Dewa Sherkole Legehida Harewa Kurmuk GOAL IMC Menge Kelela Artuma IRC Yaso Fursi IMC Erer IRC IRC IRC Jille Menz IMC Timuga Dembel Wara Afdem Bilidigilu IRC Mama Assosa IRC Jarso IMC Tarema IMC Midir Ber IRC IRC Agalometi Gerar IMC Jarso Kamashi IMC Bambasi GOAL DIRE Chinaksen IMC IMC IRC IMC DAWA IMC Bio Jiganifado Ankober Meta IRC GOAL IRC IMC IMC Aleltu Deder HARERI GOAL GOAL Gursum IRC IRC IRC GOAL Midega SOMALIA IRC IMC Goba SOUTH SUDAN Tola ACF Koricha Anfilo IMC Gashamo Anchar GOAL Daro Lebu Boke Golo Oda IRC Wantawo GOAL Meyu IMC IRC IRC IRC GOAL GOAL IMC Aware SCI IMC Fik IRC IRC Kokir Sire Jikawo IRC Gedbano Adami IMC GOAL Tulu Jido Degehabur GOAL SCI GOAL Sude Akobo Selti Kombolcha IRC IRC Lanfero Hamero Gunagado Mena Dalocha IMC GAMBELA GOAL Arsi IMC Shekosh GOAL Gololcha GOAL Negele Bale IMC Soro GOAL IMC IRC GOAL IMC Agarfa IRC Tembaro IRC IRC GOAL SCI GOAL GOAL IMC IMC Ginir CCM GOAL GOAL IRC IMC IMC GOAL GOAL IRC GOAL Sinana IMC IRC IRC Dinsho GOAL Goba IRC IMC GOAL IRC GOAL IRC Adaba CCM GOAL Berbere IMC Humbo GOAL SOMALI IMC Hulla IRC GOAL CCM GOAL GOAL GOAL PIN IRC Zala IMC IRC IRC Abaya PIN IRC Wenago Ubadebretsehay Mirab Gelana Abaya IRC GOAL GOAL SCI IRC IRC SCI Amaro OROMIA SNNPR IRC SCI CCM Bonke GOAL IRC Meda CCM SCI Welabu Legend SCI Konso IMC SCI International boundary Filtu Hudet INDIAN Agencies' locOaCtiEoAnNs and Regional boundary SCI Arero Dolobay Dolo Odo area of interventions are IMC No. -

Assessment of the Role of Agricultural Cooperatives in Input Output Market in Boke, Anchar and Darolebu Districts of West Hararghe Zone, Oromia Region, Ethiopia

Journal of Natural Sciences Research www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3186 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0921 (Online) Vol.10, No.11, 2020 Assessment of the Role of Agricultural Cooperatives in Input Output Market in Boke, Anchar and Darolebu Districts of West Hararghe Zone, Oromia Region, Ethiopia *Birhanu Angasu Tadesse Melka Gosa Alemu Jima Degaga Oromia Agricultural Research Institute, Mechara Agricultural Research Center, P.O.BOX 19, Mechara, Ethiopia Abstract The study was conducted in three districts where agricultural cooperatives have been well promoted in West Hararghe zone to identify role of primary agricultural Cooperatives and factors affecting its role in the study area. Structured interview schedule were used to collect data from 180 cooperative members and non-members selected randomly from six agricultural cooperatives and its surrounding. Focus group discussions were also conducted to collect qualitative data from respondents. In this study, the statistical tools like descriptive statistics such as mean, frequency distribution and percentage, SWOT analysis and an index score was used to rank major constraints. Out of interviewed respondents, 66.7% were member of cooperative while 33.3% were non-members of the cooperatives. Most primary cooperative mainly focuses on the activities like provision of fertilizer (DAP, UREA and NPS), consumable food items (sugar and cooking oil) and rarely involved in improved seed distributions. Lack market interest, climate change, lack of market information, insufficient capital and low price of the marketable commodity were major constraints found in agricultural commodities in study area. Strengthening training, improve their capital, services and transparency, increasing members participation, sharing dividend to the members and annual auditing their status were major recommendation delivered for responsible bodies by the study. -

Ethiopia - Livelihood Zones

ETHIOPIA - LIVELIHOOD ZONES ± Eritrea Yemen Tigray Mek'e" le Sudan " Gonder Afar Djibouti Amhara " Dese Benshangul Gumuz Debre "Markos Dire Dawa" Oromia Harar" " Addis Ababa!^ Somalia Nek'emte "Gore " Asela Gambela " Jima " " Awasa Goba Somali South Sudan SNNPR " Arba Minch 0 60 120 240 360 480 Kenya Kilometers Uganda USAID Household Economic Analysis - Activity (HEA-A)/National Disaster Risk Management Commission (NDRMC) Map Updated: 2018 AFAR REGION, ETHIOPIA - LIVELIHOOD ZONES AAP International Boundaries ± AAP Zones AAP ^! Capital AAP " AAP Cities Tigray Yemen ASP Eritrea " Afar Region - Livelihood Zones Mek'ele Kilbati AAP AAP - Asale Agropastoral AGA - Awsa-Gewane Agropastoral ARP - Aramiss - Adaar Pastoral ASP - Asale Pastoral CNO - Chenno Agropastoral " Gonder TER ELP - Eli daar Pastoral Fanti ELP NMP - Namalefan & Baadu Pastoral TER - Teru Pastoral Awusi Djibouti Amhara ARP AGA " Dese AGA Khari AGA " Debre Markos NMP Somalia Gabi AGA Somali " CNO Dire Oromia AGA Dawa Harar" " Addis Ababa^! 0 30 60 120 180 240 Kilometers AMHARA REGION, ETHIOPIA - LIVELIHOOD ZONES Tigray International Boundaries !^ Capital " ± Zones Cities " TSG Mek'ele TSG North Gondar NWB Wag NWC TSG Himra " Gonder TSG NWS TZA NMC TZR North Wollo TZA TZR NMC NWS NWE Sudan South Gondar GHL NHB ATW Afar SME WMB SWM ATW SME SME ABP ABB WMB WMB SWT South Wollo SWS WMB Awi " CBP Dese CBP Argoba SWB CBP WMB CBP ABP Oromia SWT West Gojam SWS 0 25 50 100 150 200 East ABB SME Kilometers Benshangul SWW Gojam SWT Gumuz " ABB - Abay Beshilo River Basin NWC - NorthWest Cash -

Xerox University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spiiced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Assessment Field Trip to Arsi Zone (Oromiya Region)

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Emergencies Unit for Ethiopia (EUE) Assessment field trip to Arsi zone (Oromiya Region) Field Assessment Mission: 7 – 10 April & 15 – 17 April 2003 By Francois Piguet, UN-Emergencies Unit for Ethiopia 1. Introduction and background The mission’s major objectives were to assess the humanitarian situation in Arsi, following three years of rainfall deficit. The assessment focused on general agriculture situation, livestock condition and the main humanitarian concerns, which are stressed mainly due to food insecurity at household level, water shortage, health issues and unexpected migrations of people and livestock. According to the zonal authorities, of 22 woreda in Arsi zone, 19 are affected by the prolonged drought conditions. The most affected woreda are: Dodota Sire and Zway Gugda woreda where it is estimated that last year farmers lost 95 % of their harvest, Merti and Gololcha with 80% failure and Seru 70% failure. Woreda in the lowlands suffered greatest. At the beginning of 2003 Belg rainy season, Arsi zone has experimented rain onset delays and erratic rains, but since mid-April heavy rain occurred allover the zone. Due to a long-term crop production decrease and the failure of Meher 2002 (Piguet, 2002), all affected woredas are facing seed problems. Only some composed seed and uncertified local seed are now available. At this stage, Asala seed enterprise production remains expensive and is mostly offering unsuitable seed for subsistence farmers. Almost no sorghum seed and maize katomani maize are available in Awasa and in Asela, the two main seed multiplication centers in south-east Ethiopia. -

Compendium of Environment Statisetics

COMPENDIUM OF ENVIRONMENT STATISETICS ETHIOPIA 2016 THE FEDERAL DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ETHIOPIA NATIONAL PLANNING COMMISSION CENTRAL STATISTICAL AGENCY September/ 2017 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia THE FEDERAL DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ETHIOPIA NATIONAL PLANNING COMMISSION CENTRAL STATISTICAL AGENCY September/ 2017 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Contact Persons: Mr. Habekiristos Beyene; Director: Agriculture, Natural Resource and Environment Statistics Directorate Email; [email protected] Mr. Alemesht Ayele; Senior Statistician: Agriculture, Natural Resource and Environment Statistics Directorate Email; [email protected] Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia Addis Ababa P.O.BOX 1143 Telephone: +251-1155-30-11/+251-1156-38-82 Fax: +251-1111-5574/+251-1155-03-34 Website: www.csa.gov.et Table of Contents Page Table of Contents ..................................................................................................................... i LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................. iv LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................................. vii PREFACE .............................................................................................................................. ix ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ................................................................................ x UNIT OF MEASUREMENT AND STANDARD EQUIVALENTS ..................................... xii 1. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................. -

ETHIOPIA National Disaster Risk Management Commission National Flood Alert # 2 June 2019

ETHIOPIA National Disaster Risk Management Commission National Flood Alert # 2 June 2019 NATIONAL FLOOD ALERT INTRODUCTION NMA WEATHER OUTLOOK FOR kiremt 2019 This National Flood Alert # 2 covers the Western parts of the country, i.e. Benishangul Gumuz, Gambella, Western Amhara, Western Oromia, and Western highlands of SNNPR anticipated Kiremt season, i.e. June to September to receive normal rainfall tending to above normal rainfall. 2019. The National Flood Alert # 1 was issued in April 2019 based on the NMA Eastern and parts of Central Ethiopia, western Somali, and southern belg Weather Outlook. This updated Oromia are expected to receive dominantly normal rainfall. Flood Alert is issued based on the recent Afar, most of Amhara, Northern parts of Somali and Tigray are expected NMA kiremt Weather outlook to to experience normal to below normal rainfall during the season. highlight flood risk areas that are likely to receive above normal rainfall during Occasionally, heavy rainfalls are likely to cause flash and/or river floods the season and those that are prone to in low laying areas. river and flash floods. This flood Alert Tercile rainfall probability for kiremt season, 2019 aims to prompt early warning, preparedness, mitigation and response measures. Detailed preparedness, mitigation and response measures will be outlined in the National Flood Contingency Plan that will be prepared following this Alert. The National Flood Alert will be further updated as required based on NMA monthly forecast and the N.B. It is to be noted that the NMA also indicated 1993 as the best analogue year for 2019 situation on the ground. -

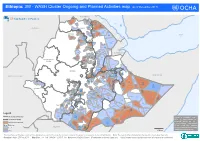

3W - WASH Cluster Ongoing and Planned Activities Map (As of December 2017)

Ethiopia: 3W - WASH Cluster Ongoing and Planned Activities map (as of December 2017) ERITREA RWB 37Total Number of Partners Ahferom ☉ Gulomekeda IRC RWB Saesie Tahtay RWB Tahtay Tsaedaemba Adiyabo JSI Koraro Dalul SCI ADCS Red Sea RWB Concern RWB VSF-Germany COOPI RWB Koneba RWB VSF-Germany SUDAN Concern TIGRAY Kelete Berahile Tselemti Awelallo Afdera Plan Concern SCI VSF-Germany RWB COOPI Bidu RWB SCI Abergele Hintalo Megale SCI AMHARA Wejirat Gulf of RWB GAA ACF RWB Erebti RWB RWB Aden Wegera ACF RWB Ziquala ACF RWB Plan JSI RWB Alamata Elidar Dehana ACF JSI RWB Gulina RWB Plan Concern Kobo AFAR Lay Guba Plan Gayint RWB Dubti RWB Lafto RWB RWB Plan Concern Habru RWB Simada Delanta LVIA CARE Adaa'r CARE Concern LVIA Mile DJIBOUTI Concern JSI Telalak RWB Kalu RWB Legambo RWB Enbise RWB RWB LVIA CARE RWB RWB Sar Midir Kelela Were Ilu Dewa Dewe Enarj Gewane Cheffa BENISHANGUL Enawga RWB Jama Bure RWB IMC GUMUZ Mudaytu Menz Gera Erer RWB RWB Midir Jille CARE IRE LVIA Shinile Timuga Afdem RWB RWB RWB Amibara IRE Oxfam Ensaro Ankober CARE Miesso RWB IMC Aw-bare RWB Kombolcha RWB RWB EOC-DICAC RWB IMC OROMIA CARE CARE RWB Oxfam Awash Mieso Deder RWB CARE DRC RWB Gursum RWB Fentale RWB Gursum NRC RWB RWB Tulo LWF CARE Mesela Oxfam Berehet Girawa IMC RWB ACF RWB Hareshen JSI ACF ACF RWB Minjar Fentale RWB SOMALIA RWB ECC-SADCO SOUTH SUDAN RWB Shenkora RWB RWB Bedeno RWB RWB CARE EOC-DICAC Gemechis WVI ChildFund Meyu RWB Midega Boset Merti Babile RWB Tola IRC RWB IRC Boke Golo Oda Gashamo RWB RWB IMC RWB Oxfam ChildFund RWB IRC RWB ADRA RWB RWB -

“Socio-Economy and Institutions” Comprises (I) Current Conditions

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Introduction The Study on “Socio-Economy and Institutions” comprises (i) current conditions of socio-economy and institutions concerning the Project, (ii) identification of constraints and (iii) proposed institutional set-up for implementation of the Master Plan. To promote successful irrigation and rural development in the Meki area, the institutional strengthening of OIDA and other concerned organizations is essential. In addition, reinforcement of the staff capability is also required. The Study was firstly made through an overall assessment of OIDA, the district administration, the peasant associations and community based farmers’ organizations to prepare the institutional building program within the framework of the Master Plan. The organizational plans consist of three (3) aspects, namely organizational development, capacity building and financial management. 1.2 Study Area The study area administratively falls in Dugda Bora Wareda (district) in East Shewa Zone of Oromia Region. It is located in the center of Oromia Region, that is the largest region in Ethiopia with a total coverage of 353,007 km2 or 32% of the national territory and provides livelihood to 22.35 million or 35% of the total national population. The main urban center of the area is Meki town located at 130 km south of Addis Ababa. The S/W seletced the proposed irrigation development area situated on the bottomland of the Rift Valley (El. 1,650 m) with a total area of 400 km2 extending to the north of the Meki town within Dugda Bora Wareda. -

Woreda-Level Crop Production Rankings in Ethiopia: a Pooled Data Approach

Woreda-Level Crop Production Rankings in Ethiopia: A Pooled Data Approach 31 January 2015 James Warner Tim Stehulak Leulsegged Kasa International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) Addis Ababa, Ethiopia INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) was established in 1975. IFPRI is one of 15 agricultural research centers that receive principal funding from governments, private foundations, and international and regional organizations, most of which are members of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). RESEARCH FOR ETHIOPIA’S AGRICULTURE POLICY (REAP): ANALYTICAL SUPPORT FOR THE AGRICULTURAL TRANSFORMATION AGENCY (ATA) IFPRI gratefully acknowledges the generous financial support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) for IFPRI REAP, a five-year project to support the Ethiopian ATA. The ATA is an innovative quasi-governmental agency with the mandate to test and evaluate various technological and institutional interventions to raise agricultural productivity, enhance market efficiency, and improve food security. REAP will support the ATA by providing research-based analysis, tracking progress, supporting strategic decision making, and documenting best practices as a global public good. DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared as an output for REAP and has not been reviewed by IFPRI’s Publication Review Committee. Any views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies or views of IFPRI, the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. AUTHORS James Warner, International Food Policy Research Institute Research Coordinator, Markets, Trade and Institutions Division, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia [email protected] Timothy Stehulak, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Research Analyst, P.O.