National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

People of Snowy Mountain, People of the River: a Multi-Agency Ethnographic Overview and Compendium Relating to Tribes Associated with Clark County, Nevada

Portland State University PDXScholar Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations Anthropology 2012 People of Snowy Mountain, People of the River: A Multi-Agency Ethnographic Overview and Compendium Relating to Tribes Associated with Clark County, Nevada Douglas Deur Portland State University, [email protected] Deborah Confer University of Washington Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anth_fac Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Deur, Douglas and Confer, Deborah, "People of Snowy Mountain, People of the River: A Multi-Agency Ethnographic Overview and Compendium Relating to Tribes Associated with Clark County, Nevada" (2012). Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations. 98. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anth_fac/98 This Report is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Pacific West Region: Social Science Series National Park Service Publication Number 2012-01 U.S. Department of the Interior PEOPLE OF SNOWY MOUNTAIN, PEOPLE OF THE RIVER: A MULTI-AGENCY ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW AND COMPENDIUM RELATING TO TRIBES ASSOCIATED WITH CLARK COUNTY, NEVADA 2012 Douglas Deur, Ph.D. and Deborah Confer LAKE MEAD AND BLACK CANYON Doc Searls Photo, Courtesy Wikimedia Commons -

The Museum of Northern Arizona Easton Collection Center 3101 N

MS-372 The Museum of Northern Arizona Easton Collection Center 3101 N. Fort Valley Road Flagstaff, AZ 86001 (928)774-5211 ext. 256 Title Harold Widdison Rock Art collection Dates 1946-2012, predominant 1983-2012 Extent 23,390 35mm color slides, 6,085 color prints, 24 35mm color negatives, 1.6 linear feet textual, 1 DVD, 4 digital files Name of Creator(s) Widdison, Harold A. Biographical History Harold Atwood Widdison was born in Salt Lake City, Utah on September 10, 1935 to Harold Edward and Margaret Lavona (née Atwood) Widdison. His only sibling, sister Joan Lavona, was born in 1940. The family moved to Helena, Montana when Widdison was 12, where he graduated from high school in 1953. He then served a two year mission for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In 1956 Widdison entered Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, graduating with a BS in sociology in 1959 and an MS in business in 1961. He was employed by the Atomic Energy Commission in Washington DC before returning to graduate school, earning his PhD in medical sociology and statistics from Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio in 1970. Dr. Widdison was a faculty member in the Sociology Department at Northern Arizona University from 1972 until his retirement in 2003. His research foci included research methods, medical sociology, complex organization, and death and dying. His interest in the latter led him to develop one of the first courses on death, grief, and bereavement, and helped establish such courses in the field on a national scale. -

WYOMING Adventure Guide from YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK to WILD WEST EXPERIENCES

WYOMING adventure guide FROM YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK TO WILD WEST EXPERIENCES TravelWyoming.com/uk • VisitTheUsa.co.uk/state/wyoming • +1 307-777-7777 WIND RIVER COUNTRY South of Yellowstone National Park is Wind River Country, famous for rodeos, cowboys, dude ranches, social powwows and home to the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho Indian tribes. You’ll find room to breathe in this playground to hike, rock climb, fish, mountain bike and see wildlife. Explore two mountain ranges and scenic byways. WindRiver.org CARBON COUNTY Go snowmobiling and cross-country skiing or explore scenic drives through mountains and prairies, keeping an eye out for foxes, coyotes, antelope and bald eagles. In Rawlins, take a guided tour of the Wyoming Frontier Prison and Museum, a popular Old West attraction. In the quiet town of Saratoga, soak in famous mineral hot springs. WyomingCarbonCounty.com CODY/YELLOWSTONE COUNTRY Visit the home of Buffalo Bill, an American icon, at the eastern gateway to Yellowstone National Park. See wildlife including bears, wolves and bison. Discover the Wild West at rodeos and gunfight reenactments. Hike through the stunning Absaroka Mountains, ride a mountain bike on the “Twisted Sister” trail and go flyfishing in the Shoshone River. YellowstoneCountry.org THE WORT HOTEL A landmark on the National Register of Historic Places, The Wort Hotel represents the Western heritage of Jackson Hole and its downtown location makes it an easy walk to shops, galleries and restaurants. Awarded Forbes Travel Guide Four-Star Award and Condé Nast Readers’ Choice Award. WortHotel.com welcome to Wyoming Lovell YELLOWSTONE Powell Sheridan BLACK TO YELLOW REGION REGION Cody Greybull Bu alo Gillette 90 90 Worland Newcastle 25 Travel Tips Thermopolis Jackson PARK TO PARK GETTING TO KNOW WYOMING REGION The rugged Rocky Mountains meet the vast Riverton Glenrock Lander High Plains (high-elevation prairie) in Casper Douglas SALT TO STONE Wyoming, which encompasses 253,348 REGION ROCKIES TO TETONS square kilometres in the western United 25 REGION States. -

2019 Visitors Guide

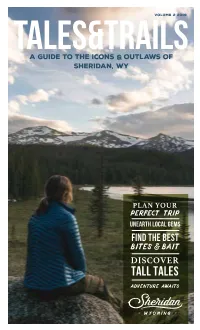

VOLUME 2 2019 TALES&TRAILS a guide to the icons & outlaws of sheridan, wy UNEARTH LOCAL GEMS TALES & TRAILS | SHERIDAN TALES&TRAILS a guide to the icons & outlaws of sheridan, wy wyoming is a The world comes out west expecting to see cowboys driving horses through the streets of downtown; pronghorn butting testament to what heads on windswept bluffs; clouds encircling the towering granite pinnacles of the Bighorn Mountains; and endless people are capable of expanses of wild, open country. These are some of the fibers that if you give them have been stitched together over time to create the patchwork quilt of Sheridan’s identity, each part and parcel to the Wyoming enough space. experience. What you may not have been expecting when you came way out West was a thriving, historic downtown district, with western allure, hospitality and good graces to spare; a - sam morton vibrant art scene; bombastic craft culture; a robust festival and events calendar; and living history on every corner. Welcome to Sheridan, the Cultural Capital of Wyoming. 44°47’48”n 106°57’32”w Sheridan has a total area of 10.95 square miles 10.93/sq miles of land | 0.02/sq miles of water ELEVATION 3,743 feet above sea level CITY POPULATION 17,954 | COUNTY POPULATION 30,210 average sunny days per year: 208 July is the warmest | January is the coldest Record High 107°F in 2002 Record Low -41°F in 1989 sheridanwyoming.org #visitsheridan 2 TALES & TRAILS | SHERIDAN MISSOULA N REGIONAL attractions TIME AND ESTIMATED MILEAGE FROM SHERIDAN, WY BUTTE 1 BIGHORN NATIONAL FOREST 35 MILES, 40 MINUTES MT Established in 1897. -

Tales& Trails

TALES& TRAILS A Guide to the Icons and Outlaws of Sheridan, WY Explore Bighorn Mountain Country EXPERIENCE WYOMING LIKE NEVER BEFORE STREAM ALL 12 EPISODES OF 12 EPISODES ALL STREAM SEASON 1 on yOUTUBE NOW yOUTUBE 1 on SEASON VOLUME 4 2021 TALES & TRAILS | SHERIDAN TALES&TRAILS a guide to the icons & outlaws of Sheridan, wy Wyoming is a The world comes out west expecting to see cowboys driving testament to what horses through the streets of downtown; pronghorn butting heads on windswept bluffs; clouds encircling the towering people are capable of granite pinnacles of the Bighorn Mountains; and endless expanses of wild, open country. These are some of the fibers that if you give them have been stitched together over time to create the patchwork enough space. quilt of Sheridan’s identity, each part and parcel to the Wyoming experience. What you may not have been expecting when you came way out West was a thriving, historic downtown district, - sam morton with western allure, hospitality and good graces to spare; a vibrant art scene; bombastic craft culture; a robust festival and events calendar; and living history on every corner. Welcome to Sheridan, the Cultural Capital of Wyoming. 44°47’48”n 106°57’32”w Sheridan has a total area of 10.95 square miles 10.93/sq miles of land | 0.02/sq miles of water ELEVATION 3,743 feet above sea level CITY POPULATION 17,954 | COUNTY POPULATION 30,210 average sunny days per year: 208 July is the warmest | January is the coldest Record High 107°F in 2002 Record Low -41°F in 1989 sheridanwyoming.org #visitsheridan 2 TALES & TRAILS | SHERIDAN MISSOULA N REGIONAL attractions TIME AND ESTIMATED MILEAGE FROM SHERIDAN, WY BUTTE 1 BIGHORN NATIONAL FOREST 35 MILES, 40 MINUTES MT Established in 1897. -

The Next Boom

Winter 2009 The Next Boom Amid the rush to develop industrial-scale wind farms, the Wyoming Outdoor Council is offering leadership on the ground. See page 3 p4 The Council welcomes Janice Harris to the board p7 Join the Outdoor Council’s Jamie 42 Wolf for a tour in the Big Horn Basin Years Photo courtesy of Chuck Fryberger Films, www.ChuckFryberger.com Message from the Director Wyoming Outdoor Council Laurie Milford, executive director Established in 1967, the Wyoming Outdoor Council is the state’s oldest and largest independent statewide conservation Launching a new program in energy policy organization. Our mission is to protect Wyoming’s environment and quality of life for future generations. Our publications come IN WYOMING, we launched a new program in energy policy. out quarterly and are a benefit of membership. are increasingly Richard Garrett, who joined our staff in Letters to the editor and articles aware that energy July 2008, has taken on the responsibility by members are welcome. development doesn’t of promoting, at the state level, policies that just affect land and remove barriers to energy efficiency and For more information contact: wildlife—that the dam- distributed—meaning locally generated— Wyoming Outdoor Council age caused by a well renewable electricity. He’ll also participate 262 Lincoln St, Lander, WY 82520 or pad doesn’t stop with a scar on the surface. in the planning and oversight of major 121 East Grand Avenue, Suite 204 The development of fossil fuels affects our sources of electricity such as power plants Laramie, WY 82070 health, and our profits, too. -

Knife River Flint Distribution and Identification in Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2016 Knife River Flint Distribution and Identification in Montana Laura Evilsizer University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Evilsizer, Laura, "Knife River Flint Distribution and Identification in Montana" (2016). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 10670. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/10670 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KNIFE RIVER FLINT DISTRIBUTION AND IDENTIFICATION IN MONTANA By Laura Jean Evilsizer B.A. Anthropology, Whitman College, Walla Walla, WA, 2011 Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology, Cultural Heritage University of Montana Missoula, MT May, 2016 Approved By: Scott Wittenburg, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Dr. Douglas H. MacDonald, Chair Department of Anthropology Dr. John Douglas Department of Anthropology Dr. Julie A. -

2010 Budget Session

2010 STATE OF WYOMING 10LSO-0035 SENATE FILE NO. SF0012 State parks and historic sites-boundaries and designations. Sponsored by: Joint Travel, Recreation, Wildlife and Cultural Resources Interim Committee A BILL for 1 AN ACT relating to state parks and historic sites; 2 designating state parks, state historic sites, state 3 archaeological sites and state recreation areas; requiring 4 legal descriptions by rule; repealing statutory legal 5 descriptions; and providing for an effective date. 6 7 Be It Enacted by the Legislature of the State of Wyoming: 8 9 Section 1. W.S. 36-8-1501 is created to read: 10 11 ARTICLE 15 12 OTHER DESIGNATIONS 13 14 36-8-1501. State park designation; state historic 15 site designation; state archeological site designation; 16 state recreation area designation. 1 SF0012 2010 STATE OF WYOMING 10LSO-0035 1 2 (a) In addition to state parks designated in other 3 statutes, the following lands are designated as state parks 4 and the department shall by rule specify the legal 5 description of the parks: 6 7 (i) The state-owned lands in Fremont County 8 managed by the department as of July 1, 2010 as Boysen 9 state park; 10 11 (ii) The state-owned lands in Park County 12 managed by the department as of July 1, 2010 as Buffalo 13 Bill state park; 14 15 (iii) The state-owned lands in Natrona County 16 managed by the department as of July 1, 2010 as Edna 17 Kimball Wilkins state park; 18 19 (iv) The state-owned lands in Platte County 20 managed by the department as of July 1, 2010 as Glendo 21 state park; 22 2 SF0012 2010 STATE OF WYOMING 10LSO-0035 1 (v) The state-owned lands in Platte County 2 managed by the department as of July 1, 2010 as Guernsey 3 state park; 4 5 (vi) The state-owned lands in Crook County 6 managed by the department as of July 1, 2010 as Keyhole 7 state park; 8 9 (vii) The state-owned lands in Carbon County 10 managed by the department as of July 1, 2010 as Seminole 11 state park. -

SOAR 2021 Wyoming State Parks, Historic

Kite Festival at Hot Springs State Park SOAR 2021 Wyoming State Parks, Historic Black & Orange Cabins at Fort Bridger Sites & Trails Strategic Plan Kayaking at Curt Gowdy State Park CCC Castle at Guernsey State Park Broom Making at Wyoming Terrorial Prison Table of Contents Acknowledgements.................................................................................2 Executive Summary.................................................................................3 Mission and Vision Statement...............................................................5 Introduction..............................................................................................6 Information.Collection........................................................................6 Wyoming.Tourism.Industry.Master.Plan,.2010.–.2020...................6 Development.of.the.SOAR..................................................................7 Implementation.and.Tracking.Progress.Of..The.SOAR......................7 SPHST Overview and Statistics..............................................................8 Philosophy...........................................................................................8 Function...............................................................................................8 Organization/Staffing....................................................................... 10 Facilities............................................................................................ 11 History.............................................................................................. -

The History of the Petroglyphs and a Preview of the Festival SIERRA VIEWS October 2018

SIERRA VIEWS October 2018 In this issue: The history of the Petroglyphs and a preview of the festival SIERRA VIEWS October 2018 Publisher John Watkins Editor Aaron Crutchfield Advertising Director Paula McKay Advertising Sales Rodney Preul; Gerald Elford Writers Jessica Weston; Andrew Salmi; Russ and Lori Tice Inside this issue: Community scares up Halloween spirit ............... 3 Ridgecrest’s Petroglyph History............................ 7 What are the Petroglyphs? ................................... 8 The Petroglyph Artists,Ancient and Modern ..... 13 Climbing, Community, and Brews ...................... 15 Why drive to Mammoth when you can fly? ....... 17 To our readers: East Kern Visions is now Sierra Views. This rebranding offers us a chance to broaden the publication’s scope, expanding from the areas of the mountains and deserts of eastern Kern County to now cover the area up and down the Eastern Sierra and beyond. In this issue, we feature Halloween fun, and check out climbing opportunities in Bishop. On the cover: A view of the petroglyphs at Petroglyph Park in Ridgecrest. The fifth annual Petroglyph Festival is set for the first weekend in November. 2 OCTOBER 2018 SIERRA VIEWS Community scares up Halloween spirit BY JESSICA WESTON The Daily Independent ays are growing shorter, the nights are growing cooler, and Halloween is in the air. A number of local events are planned to take advantage of the Dwitching time of year. The weekend before Halloween will kick off early with the Pumpkin Patch at the Ridgecrest Farmer’s Market at the Tractor Supply Co. This family-friendly event kicks off at 8 a.m. Friday, Oct. 26, in the parking lot of the Tractor Supply Co. -

February Program

http://coloradorockart.org/ February 2020 Volume 11 Issue 2 Inside This Issue 1, 3 Webinar information February Program 2 Contacts, CRAA Board News 2, 12-14 Upcoming Events Your Guess Is as Good as Any: 4-11 Rock Art Blog Authority, Ownership, and 11 Spring PAAC schedule Ethics in the Public Interpretation of Rock Art Zoom link http://zoom.us/j/6136944443 Date & Time: Thursday, February 27, 6:55 – 8:00 pm MST Need webinar help? Location: Click on http://zoom.us/j/6136944443 any time after 6:45 see page 3 pm. Program will start at 7 pm. Upcoming CRAA webinar: Presenter: Dr. Richard Rogers, Professor of Communication Studies and Associate Faculty in Women’s and Gender Studies, Northern March 24—Nicole Lohman, Arizona University BLM presents "The Spark that Lit a Fire: Impacts of a Rock Art Description: Interpretive signs at rock art sites, pamphlets available Organization on a Young at trailheads, and displays in visitor centers and museums have sub- Professional." stantial potential to shape people’s understandings of rock art and indigenous peoples. The U.S. rock art literature, however, offers little in the way of systematic analysis or guidelines for “best practices” in the public interpretation of rock art. The public wants to know, above all, what it means. However, sometimes that knowledge does not exist, sometimes the public dissemination of that knowledge is constrained, sometimes meanings may be funda- mentally contested, and sometimes “meaning” is not the only or most relevant information to share. The public interpretation of rock art involves issues of representation, ownership, and authority that complicate any simple sense of interpretation as “Here’s what we know. -

Montana (201 Citations) Compiled by Leigh Marymor Pt

Rock Art Studies: A Bibliographic Database Page 1 United States: Montana (201 citations) Compiled by Leigh Marymor Pt. Richmond CA 02/20/16 Anonymous Lookout Cave, 24PH402, Montana. United States. North America. Dark zone rock art. 1961 Biblio. "Montana Pictograph Survey" in The Wyoming Archaeologist, Vol. 4(5):6, Wyoming Archaeological Society, Sheridan, Wyoming. Barry, P.S. ISSN: 0043-9665. 1991 Mystical Themes in Milk River Rock Art, :129+ MONTANA. NORTHWESTERN PLAINS. United States. pgs, University of Alberta Press, Edmonton, North America. PICTOGRAPH SURVEY. RABNPV. Canada. MILK RIVER, WRITING-ON-STONE, ALBERTA, CANADA. MONTANA. United States. North America. Anonymous PLAINS INDIAN ROCK ART. SHAMANISM. HUMAN 1961 FIGURE (SPIRIT IN HUMAN GUISE), SHIELD "Montana Pictograph Site Visited" in The BEARING FIGURES, SKELETAL FIGURES, HEART Wyoming Archaeologist, Vol. 4(7):3, Wyoming LINE, PHALLUS, CUP-AND-GROOVE, VULVA, YONI, BOW-SHAPED ANIMALS, MONUMENTALLY LARGE Archaeological Society, Sheridan, Wyoming. ANIMALS, BIRD, HORSE MOTIF(S). ISSN: 0043-9665. LMRAA. MONTANA. NORTHWESTERN PLAINS. United States. North America. PICTOGRAPH SITE. Biddle, Nicholas, ed. RABNPV. 1962 The Journals of the Expedition of Capts. Lewis Arthur, George and Clark to the Sources of the Missouri, thence 1961 across the Rocky Mountians and down the River "Pictographs in Central Montana: Part III - Columbia to the Pacific Ocean, performed during Comments" in Montana State University the years 1804-5 - 6 by Order of the Government Anthropology and Sociology Papers, (21):41-44, of the United States, Vol. 2 volumes:540 pgs, Montana State University, Missoula, Montana. The Heritage Press, New York, New York. Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Montana. United States.