Divine Art Recordings Group Reviews Portfolio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

119 JULY-AUGUST 2015 119La Foto the PHOTO a Cura Di Massimiliano Filosto

Anno XXI n° 119 (3/2015) - €3,00 - Poste Italiane S.p.A. - Sped. in Abb. Postale - D.L. 353/2003 (conv. in L. 27/02/2004 n.46) art. 1, comma 1, DCB filiale Bologna. J L U U L G Y L - A I O U - G A U G S O T S 2 T 0 O 1 2 5 0 1 5 Sommario EDITORIALE 5 Laudato sì: l’eco-Enciclica di Papa Francesco SICUREZZA 40 Non correte ma… non pagate a scatola chiusa NOTIZIE 6 Taraxagum, il primo pneumatico in gomma di tarassaco PENSA VERDE 41 Vacanze sostenibili con BarattoBB 6 Il biogas di Linköping AUTO NOVITÀ 41 Ripartiamo da Zero 7 La discoteca mobile. Nissan e-NV200 elettrico diventa PART e-VAN LIBRI 41 L’Italia del Biologico 7 La ‘Carbon Footprint’ di 52 trattori stradali Cargo Service MUSICA 42 Miatralvia: musica con la spazzatura 7 BlaBlaCar, quanto si rispramia con il Ride Sharing CINEMA 42 The Reach - Caccia all’uomo POLITICA 8 Partono in 671 Comuni gli incentivi per la trasformazione a GPL SPORT 42 Valentino: un casco per lanciare la sua ecosostenibilità e metano per auto e mezzi commerciali 43 LE PAGINE AZZURRE DEL GAS AUTO EVENTI 9 Ecorally 2015, vince ancora l’ecomobilità 16 Si continua a correre per l’ambiente 50 INCONTRIAMOCI A… dal 15 luglio al 27 ottobre 2015 GLOSSARIO AUTOMOBILISTICO LKS - MultiAir - Multilink - Park Assistant FIERE 18 Autopromotec 2015, 1.587 espositori e oltre 100mila visitatori 20 Gas per Auto… promotec IN PROVA 24 Giulietta GPL alla prova Ecorally INCENTIVI 28 Veicoli ecologici: contributi a privati e imprese AFTER MARKET 32 Guida per l’installazione di sistemi GPL e metano LUGLIO-AGOSTO 2015 ECOLISTINO 34 Caratteristiche e prezzi dei veicoli ecologici in Italia 119 JULY-AUGUST 2015 119La Foto THE PHOTO a cura di Massimiliano Filosto Per la prima volta un veicolo Diesel Dual Fuel corre nel campionato For the first time a Diesel Dual Fuel vehicle participates in the BRITCAR BRITCAR. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2017). Michael Finnissy - The Piano Music (10 and 11) - Brochure from Conference 'Bright Futures, Dark Pasts'. This is the other version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17523/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] BRIGHT FUTURES, DARK PASTS Michael Finnissy at 70 Conference at City, University of London January 19th-20th 2017 Bright Futures, Dark Pasts Michael Finnissy at 70 After over twenty-five years sustained engagement with the music of Michael Finnissy, it is my great pleasure finally to be able to convene a conference on his work. This event should help to stimulate active dialogue between composers, performers and musicologists with an interest in Finnissy’s work, all from distinct perspectives. It is almost twenty years since the publication of Uncommon Ground: The Music of Michael Finnissy (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998). -

Ecorally Press

ECORALLY Internazionale FIA e 5° Ecorally Press Le auto più ecologiche da san marino al vaticano, due giorni on the road Vetture a GPL, metano, ibride e biocarburanti, equipaggi solitari e racing team, amatori e professionisti. L’8° Ecorally San Marino – Città del Vaticano e il 5° Ecorally Press, competizioni di regolarità dedicate ai veicoli ecologici in programma questo week- end, 18 (verifiche tecniche), 19 e 20 ottobre (gara), ospitano realtà e propulsioni diversissimi e affascinanti. Accomunati da un unico scopo: dimostrare che i veicoli ecologici sono attuali, disponibili e performanti, come tutte le altre auto circolanti sulle strade, salvo essere meno inquinanti. Accompagna la carovana di auto verso San Pietro, come nel 2012, la trasmissione televisiva di Rai 1 dedicata al mondo dei motori Easy Driver, presenti il conduttore Marcellino Mariucci e il regista Antonio Sottile, anche loro rigorosamente a bordo di auto ecologiche, una Opel Adam alimentata a GPL, in collaborazione con Uiga, e una Toyota FJ Cruiser a Metano e Bioetanolo. Vincitore delle prime tre edizioni, gareggia nel 5° Ecorally Press Roberto Chiodi, insieme al giornalista e conduttore Rai Oliviero Beha, sulla “eco-papamobile”, una Renault R4 bianca trasformata a GPL in collaborazione con Punto Gas di Roma. Presente per il quinto anno consecutivo nel Press anche l’Automobile Club d’Italia, due le auto in gara. Su Toyota Auris Hybrid del Centro di Guida Sicura ACI-Sara di Vallelunga, per il progetto ACI 3.000 automobilisti stranieri ‘Ambasciatori della Sicurezza Stradale’ e per la promozione della mobilità sostenibile, Andrea Cauli e Paolo Benevolo, ufficio stampa ACI, rispettivamente insieme a Massimo De Donato, direttore della rivista Tir e all’Ing. -

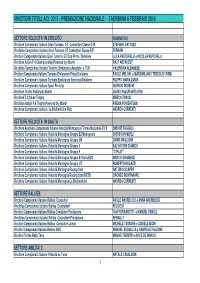

Campioni 8 Gennaio

VINCITORI TITOLI ACI 2015 - PREMIAZIONE NAZIONALE - TAORMINA 6 FEBBRAIO 2016 SETTORE VELOCITA’ IN CIRCUITO NOMINATIVO Vincitore Campionato Italiano Gran Turismo GT Conduttori Classe GT3 STEFANO GATTUSO Vincitrice Campionato Italiano Gran Turismo GT Costruttori Classe GT3 FERRARI Vincitori Campionato Italiano Gran Turismo GT Cup Prima Divisione LUCA PASTORELLI e NICOLA PASTORELLI Vincitore Italian F.4 Championship Powered by Abarth RALF ARON (EST) VincitrIce Campionato Italiano Turismo Endurance Assoluto e TCR VALENTINA ALBANESE Vincitori Campionato Italiano Turismo Endurance Prima Divisione PAOLO MELONI e MASSIMILIANO TRESOLDI (RSM) Vincitore Campionato Italiano Turismo Endurance Seconda Divisione FILIPPO MARIA ZANIN Vincitore Campionato Italiano Sport Prototipi GIORGIO MONDINI Vincitore Trofeo Nazionale Abarth JUUSO PAJIURANTA (FIN) Vincitore F.2 Italian Trophy MARCO ZANASI Vincitrice Italian F.4 Trophy Powered by Abarth PREMA POWERTEAM Vincitore Campionato Italiano Le Bicilindriche Pista ANDREA CURRENTI SETTORE VELOCITA’ IN SALITA Vincitore Assoluto Campionato Italiano Velocità Montagna e Trofeo Nazionale E2 B SIMONE FAGGIOLI Vincitore Campionato Italiano Velocità Montagna Gruppo E2 Monoposto CHRISTIAN MERLI Vincitore Campionato Italiano Velocità Montagna Gruppo CN OMAR MAGLIONA Vincitore Campionato Italiano Velocità Montagna Gruppo A SALVATORE D'AMICO Vincitore Campionato Italiano Velocità Montagna Gruppo N "O'PLAY" Vincitore Campionato Italiano Velocità Montagna Gruppo E1 Italia/E2S MARCO GRAMENZI Vincitore Campionato Italiano Velocità -

Team Ecomotori, Cinque Volte Campioni a Metano!

competizioni sportive Team Ecomotori, cinque volte campioni a metano! Dopo il successo della stagione 2012 la tensione è al massimo ma arriva la prima te- Cinque titoli sui cinque riconfermarsi era francamente difficile gola: una foratura durante la ricognizione! Que- e migliorarsi un obiettivo ambizioso an- sto non ci permette di completare l’analisi del disponibili nel 2013, che per i più ottimisti. Da una parte la percorso per avere i riferimenti indispensabili in pressione psicologica per aver conqui- una gara tirata e veloce come questa. In gara nove titoli in soli due anni, stato la fiducia di Abarth e con essa il sopraggiunge anche la febbre al pilota e, tanto supporto ufficiale, dall’altra un parterre per non farsi mancare nulla, anche problemi di trionfo assoluto con di sfidanti sempre più ampio e sempre surriscaldamento ai freni. più tecnicamente preparato, ma alla fine una doppietta nell’ultima gara i risultati sono arrivati. I primi punti La seconda tappa del Mondiale è in Spagna, del Campionato Mondiale Ancora una volta il perfetto lavoro di una squa- nei Paesi Baschi per il 5° EcoRallye Vasco Na- dra sempre più unita ha avuto la meglio ma il ri- varro. La partenza da Vitoria-gasteiz quest’anno Energie Alternative 2013 sultato finale non deve lasciare immaginare che ci regala una sorpresa: l’apertura di un nuovo sia stata una facile cavalcata a metano verso distributore di metano proprio nei pressi della e primo posto anche la vittoria perchè il campionato 2013 è iniziato partenza. Purtroppo però le dose di sfortuna del inaspettatamente in salita. -

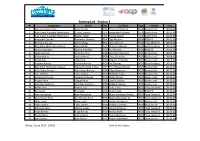

Starting List

Starting List - Section 2 Nº Competitor Driver Nac Co-Driver Nac Vehicle Hour 1 Go + Cars Go+ Eauto Artur Prusak POL Thierry Benchetrit FRA Renault Zoe 08:00:00 2 Audi Team Autotest Motorsport Guido Guerrini ITA Emanuele Calchetti ITA Audi E-Tron 08:01:00 3 Audi Team Autotest Motorsport Walter Kofler ITA Franco Gaioni ITA Audi E-Tron 08:02:00 4 Alexandre Stricher Alexandre Stricher FRA Ugo Missana FRA BMW I3 08:03:00 5 Red Cow Racing Didier Malga FRA Anne Bonnel FRA Tesla Model 3 08:04:00 6 Real Peña Motorista Vizcaya Javier Molto ESP Alionso Askondo ESP Hyundai Ioniq 08:05:00 7 Sancho Ramalho Sancho Ramalho POR Rui Martins POR BMW I3 08:06:00 8 Nuno Serrano Nuno Serrano POR Alexandre Berardo POR Renault Zoe 08:07:00 9 Pedro Morais Pedro Morais POR Silvia Coutinho POR Nissan Leaf 08:08:00 10 Pedro Dias Pedro Dias POR Miguel Fernandes POR Nissan Leaf 08:09:00 11 António Ramos António Ramos POR Ivo Tavares POR Hyundai Ioniq 08:10:00 12 Real Peña Motorista Vizcaya Txema Foronda Antiza ESP Pilar Rodas Andujar ESP Renault Zoe 08:11:00 14 João Vieira Borges João Vieira Borges POR Filipe Menezes POR Renault Zoe 08:12:00 15 Luis Teixeira Luis Teixeira POR Natércia Costa POR Nissan Leaf 08:13:00 16 Dimantino Nunes Dimantino Nunes POR Maria Nunes POR Nissan Leaf 08:14:00 17 Miguel Faria Miguel Faria POR José Sá Santos POR Nissan Leaf 08:15:00 18 Henrique Sanchez Henrique Sanchez POR Anabela Aiveca POR Nissan Leaf 08:16:00 19 Pedro Faria Pedro Faria POR Carla Faria POR Tesla Roadster 08:17:00 20 Rui Paulo Rui Paulo POR Jorge Paulo POR BMW I3 08:18:00 -

Composer-Legislators in Fascist Italy

COMPOSER-LEGISLATORS IN FASCIST ITALY: DISTINGUISHING THE PERSONAL AND LEGISLATIVE VOICES OF ADRIANO LUALDI by Kevin Robb Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia April 2020 Ó Copyright by Kevin Robb 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS USED ................................................................................ iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. v CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER II: EXPANDED LITERATURE REVIEW ................................................... 22 CHAPTER III: THE PERSONAL VOICE OF ADRIANO LUALDI ............................. 39 CHAPTER IV: THE LEGISLATIVE VOICE OF ADRIANO LUALDI ........................ 62 CHAPTER V: CONCLUSION ........................................................................................ 82 BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................. 88 APPENDIX A ................................................................................................................... 93 APPENDIX B ................................................................................................................... 98 ii ABSTRACT During -

Classifiche Campionato 2019

Green Endurance 2019 Campionato Italiano Energy Saving Classifica ASSOLUTA Piloti TOTALE 1° Aci Como EcoGreen 1° Ecodolomites GT 2019 1° Sesa Green Endurance Este Nicola Ventura 25 25 25 75 Vincenzo Di Bella 12 15 18 45 Cesare Martino - 18 15 33 Marcello Galullo - 12 10 22 Guido Guerrini 18 - - 18 Maurizio Verini 15 - - 15 Gaetana Angino - - 12 12 Domenico Palermo - 10 - 10 Lucrezia Bassani 10 - - 10 Roberto Avagliano 8 - - 8 Luca Cuomo - - 8 8 Mauro Marelli 6 - - 6 Paolo Roasio - - 6 6 Lorenzo Rossi 4 - - 4 Mario Montanucci Pignatelli 2 - - 2 Michela Caldara 1 - - 1 Giovanna Pasello - - - 0 Irene Franceschi - - - 0 Lukasz Nytko - - - 0 Tania Gandola - - - 0 Green Endurance 2019 Campionato Italiano Energy Saving Classifica ASSOLUTA Navigatori TOTALE 1° Aci Como EcoGreen 1° Ecodolomites GT 2019 1° Sesa Green Endurance Este Daniela Marchisio 25 25 25 75 Francesca Olivoni 18 18 15 51 Claudio Canale 12 15 18 45 Roberto Bernardini - 12 10 22 Francesco Gianmarino 15 - - 15 Alessandro Moretti - - 12 12 Giovanna Laura Caldara 10 - - 10 Giordano Regazzo - 10 - 10 Giorgio Barni 8 - - 8 Francesca Bianco - - 8 8 Domenico Ronchetti 6 - - 6 Claudia Marchisio - - 6 6 Ruggero Pignatta 4 - - 4 Annalisa Zortea 2 - - 2 Stefano Ferrario 1 - - 1 Monica Pasello - - - 0 Emma Parmeggiani - - - 0 Patrycja Sitarz - - - 0 Massimo Polizzotto - - - 0 Green Endurance 2019 Campionato Italiano Energy Saving Classifica ASSOLUTA Scuderie TOTALE 1° Aci Como EcoGreen 1° Ecodolomites GT 2019 1° Sesa Green Endurance Este Ecomotori Racing Team 25 25 25 75 ADS Scuderia Etruria -

© 2014 Daniele De Feo ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2014 Daniele De Feo ALL RIGHTS RESERVED IL GUSTO DELLA MODERNITÀ: AESTHETICS, NATION, AND THE LANGUAGE OF FOOD IN 19TH CENTURY ITALY By DANIELE DE FEO A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Italian Written under the direction of Professor Paola Gambarota And approved by _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey January, 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION IL GUSTO DELLA MODERNITÀ: AESTHETICS, NATION, AND THE LANGUAGE OF FOOD IN 19TH CENTURY ITALY By DANIELE DE FEO Dissertation Director Professor Paola Gambarota My dissertation “Il Gusto della Modernità: Aesthetics, Nation and the Language of Food in 19th century Italy,” explores the cohesive pedagogic and nationalistic attempt to define Italian taste during the instability of an unificatory Italy. Initiating with an establishing European taste paradigm (e.g. Feuerbach, Fourier, Brillat-Savarin), my research demonstrates that there is an increasing number of works composed within the developing “Italian” context, which reflects and participates in the construction and the consumption of a national identity (e.g., Rajberti, Mantegazza, Guerrini, Artusi). Conversely, this budding taste genre finds itself in sharp contrast to the economic paucity and social divisiveness endured by a large sector of the populace and depicted by the literature of the day (e.g., Collodi, Verga, Serao). It is precisely this lack of confluence between that which is scientific and literary that marks this process of taste ennoblement and indoctrination, defining more than ever the nuances that encompass il gusto italiano. -

Ecomotori Racing Team: Three-Time World Champions

Press Release ECOMOTORI RACING TEAM: THREE-TIME WORLD CHAMPIONS For the third year in a row, Ecomotori.net’s Fiat 500 Abarth has won the World Championship for Alternative Energies, making it the most decorated Abarth ever. Milan, Italy – October 8th 2014 - The Ecomotori Racing Team’s CNG-converted Fiat 500 EcoAbarth has won the 2014 FIA Alternative Energies Cup for the third year in a row. The driver, Massimo Liverani, was also crowned World Champion in the Drivers' and Manufacturers' categories. The last race played a crucial role in determining the final results. Called the Hi-Tech EKO-Mobility Rally, it was held last Saturday and Sunday (October 4th and 5th) in Greece, on a course of more than 500 km through the Hellenic nation from Nea Filadelfeia to Athens and back. Massimo Liverani came in first place, followed by Guido Guerrini in an LPG-powered Alfa Mito and the Greek Denis Negkas in a Toyota Prius. Ecomotori Racing Team Manager Nicola Ventura had this to say on the win: "For the third year in a row, we’re at the top of the World Championship. Everything worked perfectly and in Greece we proved the value of our team once again. We’ve won 13 out of the 15 races that the team has taken part in over the last three years, so winning is our identity and we are proud of it. With this race, the 500 EcoAbarth, equipped with a Cavagna/Bigas CNG conversion kit, finishes up its career in the World FIA Alternative Energies Cup on a victorious note. -

Lista De Inscritos - Entry List

FIA E-RALLYE REGULARITY CUP CAMPEONATO DE ESPAÑA DE ENERGIAS ALTERNATIVAS LISTA DE INSCRITOS - ENTRY LIST DORSAL EQUIPO PILOTO COPILOTO VEHÍCULO MODELO CAT FIA RFEDA 1 Audi Team Autotest Motorsport Walter Fuzzy Kofler Franco Gaioni Audi E‐Tron ELÉCTRICO SI NO 2 Artur Prusak Artur Prusak Thierry Benchetrit BMW i3s ELÉCTRICO SI NO 3 Audi Team Autotest Motorsport Guido Guerrini Emanuele Calchetti Audi E‐Tron ELÉCTRICO SI NO 4 Red Cow Racing Didier Malga Anne Bonnell Tesla Model 3 ELÉCTRICO SI NO 5 Electrip Raoul Henri Fesquet Caroline Brams Tesla Model 3 ELÉCTRICO SI NO 6 Hyunbisa Txema Foronda Pilar Rodas Hyundai Kona ELÉCTRICO SI SI 7 RPMV Javier Moltó Ana Moltó Kia e‐Niro ELÉCTRICO SI SI 8 Blendio Parayas Ricardo González José Manuel Salas Nissan Leaf ELÉCTRICO SI SI 9 Gaursa Zósimo Hernández Miguel Dávila Renault Zoe ELÉCTRICO SI SI 10 IBIL Asier Santamaría Roberto Rentería Hyundai Kona ELÉCTRICO SI SI 11 Gaursa Ignacio Bañares Alfonso Oiarbide Renault Zoe ELÉCTRICO SI SI 12 RPMV Jose Luis Etxabe Germán Núñez Hyundai Ioniq ELÉCTRICO SI SI 14 Autonervión Sergio Urrestarazu Jesús Gil Renault Zoe ELÉCTRICO SI SI 15 RPMV Jose Manuel Cortés Joseba Rodríguez Hyundai Kona ELÉCTRICO SI SI 16 Gaursa Manu Bilbao Ibai Bilbao Nissan Leaf ELÉCTRICO SI SI 17 Lurauto Iker Reketa Koldo Cepeda BMW i3s ELÉCTRICO SI SI 18 Petronor Xabier Begoña Eduardo Díez Renault Zoe ELÉCTRICO SI SI 19 Petronor Oscar Villanueva Manuel Núñez Jaguar I‐Pace ELÉCTRICO SI SI 20 RPMV José Miguel Aguirregabiria Estibaliz Barañano Sainz Aja Tesla Model 3 ELÉCTRICO SI SI 21 Autonervión -

Luca Lombardi CONSTRUCTION of FREEDOM

Luca Lombardi CONSTRUCTION OF FREEDOM COLLECTION D’ÉTUDES MUSICOLOGIQUES SAMMLUNG MUSIKWISSENSCHAFTLICHER ABHANDLUNGEN Volume 97 LUCA LOMBARDI CONSTRUCTION OF FREEDOM and other writings Translated by THOMAS DONNAN and JÜRGEN THYM Edited by JÜRGEN THYM With Lists of the Composer’s Writings and Works by GABRIELE BECHERI 2006 VERLAG VALENTIN KOERNER • BADEN-BADEN Luca Lombardi: Construction of Freedom and other writings./ Translated by Thomas Donnan and Jürgen Thym. Edited by Jürgen Thym Luca Lombardi – Baden-Baden: Koerner 2006 (Sammlung musikwissenschaftlicher Abhandlungen 97) ISBN 3-87320-597-1 ISSN 0085-588x Photograph of Luca Lombardi: © Roberto Masotti Alle Rechte vorbehalten © 2006 Printed in Germany Luca Lombardi is an important composer of our time and also an important thinker in matters musical, especially when it comes to issues involving the often tricky relations between music and society. For that reason I salute the publication at hand that makes Lombardi’s widely-scattered writings available, at least in form of a selection, in one volume: not only in trans- lations in English but, in the appendix, also in their Italian and German originals. What wealth (and also what clarity) of thoughts and insights during difficult and critical decades—years that witnessed developments and paradigm shifts of historical significance, both politically and musically. I admire the intellectual honesty as much as the consistency of thought that manifests itself in the texts: Lombardi is an author who remains faithful to himself, even (or precisely) when he considers it necessary to revise earlier opinions. As in his music, he formulates his positions with precision, poignancy, and wit—in that respect he is the heir to the classical tradition of his native land with which he grew up.