Chapter 2 Contracting Nomadic Carriage for an Aquatic Agenda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microbial Cellulases and Their Industrial Applications

SAGE-Hindawi Access to Research Enzyme Research Volume 2011, Article ID 280696, 10 pages doi:10.4061/2011/280696 Review Article Microbial Cellulases and Their Industrial Applications Ramesh Chander Kuhad,1 Rishi Gupta,1 and Ajay Singh2 1 Lignocellulose Biotechnology Laboratory, Department of Microbiology, University of Delhi South Campus, New Delhi 110021, India 2 Research & Development Division, Lystek International Inc., Waterloo, ON, Canada N2J 3H8 Correspondence should be addressed to Ramesh Chander Kuhad, [email protected] Received 14 May 2011; Accepted 9 July 2011 Academic Editor: Alane Beatriz Vermelho Copyright © 2011 Ramesh Chander Kuhad et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Microbial cellulases have shown their potential application in various industries including pulp and paper, textile, laundry, biofuel production, food and feed industry, brewing, and agriculture. Due to the complexity of enzyme system and immense industrial potential, cellulases have been a potential candidate for research by both the academic and industrial research groups. Nowadays, significant attentions have been devoted to the current knowledge of cellulase production and the challenges in cellulase research especially in the direction of improving the process economics of various industries. Scientific and technological developments and the future prospects for application of cellulases in different industries are discussed in this paper. 1. Introduction of cellulosomes-cohesin containing scaffolding and dockerin containing enzyme. The free cellulase contains cellulose Biotechnological conversion of cellulosic biomass is poten- binding domains (CBMs), which are replaced by a dockerin tially sustainable approach to develop novel bioprocesses in cellulosomal complex, and a single scaffolding-born CBM and products. -

The Serpentine Essence of a Chancay Gauze Headdress

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2008 The Serpentine Essence of a Chancay Gauze Headdress Jessica Gerschultz Emory University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Gerschultz, Jessica, "The Serpentine Essence of a Chancay Gauze Headdress" (2008). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 94. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/94 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Serpentine Essence of a Chancay Gauze Headdress Jessica Gerschultz [email protected] A small but fascinating Chancay gauze fragment in the collection of the Michael C. Carlos Museum stands out as an exemplary object that embodies the symbolic associations and aesthetic principles of the Peruvian coastline during the Late Intermediate Period (Fig. 1).1 Its weave structure, production process, iconography, and polychromy unite in reinforcing the protective and regenerative purposes of the original headdress. Consisting of variably spun threads knotted together, its unique discontinuous warp relates to its function in funerary and ceremonial contexts. Significantly, its weaver pushed beyond technical limitations to bring together the laborious techniques of gauze weaving and discontinuous warping in a single textile.2 The result of this ingenious yet unpublished technical combination was a “jumping” serpentine figure on an indigo background. -

Catazacke 20200425 Bd.Pdf

Provenances Museum Deaccessions The National Museum of the Philippines The Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University New York, USA The Monterey Museum of Art, USA The Abrons Arts Center, New York, USA Private Estate and Collection Provenances Justus Blank, Dutch East India Company Georg Weifert (1850-1937), Federal Bank of the Kingdom of Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia Sir William Roy Hodgson (1892-1958), Lieutenant Colonel, CMG, OBE Jerrold Schecter, The Wall Street Journal Anne Marie Wood (1931-2019), Warwickshire, United Kingdom Brian Lister (19262014), Widdington, United Kingdom Léonce Filatriau (*1875), France S. X. Constantinidi, London, United Kingdom James Henry Taylor, Royal Navy Sub-Lieutenant, HM Naval Base Tamar, Hong Kong Alexandre Iolas (19071987), Greece Anthony du Boulay, Honorary Adviser on Ceramics to the National Trust, United Kingdom, Chairman of the French Porcelain Society Robert Bob Mayer and Beatrice Buddy Cummings Mayer, The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Chicago Leslie Gifford Kilborn (18951972), The University of Hong Kong Traudi and Peter Plesch, United Kingdom Reinhold Hofstätter, Vienna, Austria Sir Thomas Jackson (1841-1915), 1st Baronet, United Kingdom Richard Nathanson (d. 2018), United Kingdom Dr. W. D. Franz (1915-2005), North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany Josette and Théo Schulmann, Paris, France Neil Cole, Toronto, Canada Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald (19021982) Arthur Huc (1854-1932), La Dépêche du Midi, Toulouse, France Dame Eva Turner (18921990), DBE Sir Jeremy Lever KCMG, University -

Checklist for Textiles U.S.A

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 11 WEST 53 STREET, NEW YORK 19, N. Y. TELEPHONE: CIRCLE 5-8900 No. &• TENTATIVE AND CONFIDENTIAL CHECKLIST FOR TEXTILES U.S.A. Home Furnishings Category Anderson Studio of Handweaving - East Gloucester, Massachusetts. Drapery material. Cotton, viscose and Jute. Designed by Beatrice Anderson, 1951*. Thelma Becherer - West Franklin, New Hampshire. Tapestry. Handwoven of green, yellow and clear "velon" plastic, with dried horsetails and cattails. Plain weave. 1956. Monica Bella Broner, Tapestry. "Fur Weave." Wool, cotton and fur strips, 195^• Bill Carter and Dodie Childs - Chicago, Illinois. Roll Shade, Handwoven matchstick bamboo across multicolored and textured cotton, wool and metallic yarn warp, 1955* Arundell Clarke Drapery fabric. "Strocm Draden". Handscreened white print on trans parent white silk. Designed by Pierre Kleykamp, 1955. Drapery fabric, "Primitive Forms." Handscreened black print on brown cotton. Designed by Baldwin-Machado, 1950, Drapery fabric. "10,000 B.C." Cotton jacquard, charcoal on white. Designed by Naomi Raymond, 1952. Cohn-Hall-Marx Co, (For Colvin, see Bertha Schaefer Callery - Page 3.) Upholstery fabric, Saran and metal, novelty weave. Brown, 1955. Fazakas Fabrics, Inc. Drapery fabric, "Hit & Miss," Black spray on white cotton batiste, Designed by DoneIda Fazakas, 1950, Qeraldine Punk - Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Window ahade, Handwoven red and rust cotton and rayon warp. Banana bark and coconut cord weft. 1950, Screen, Handwoven in Puerto Rico, White string warp,, white jnaguey and coconut sliver weft, 19^8, % Ginstrom - Cedar Falls, Iowa. Screen. "Scallops." Handwoven, handtied openwork; all linen panel. 1955. folding Decorative Fabrics. Drapery fabric. "Torero-Vermilion 33." Silk screened cotton sateen. Designed by Otto and Grete Wollner,1955» LiUy E. -

Full Article-PDF

Sharada.R et al IJCPS, 2014, Vol.2(8): 1082-1094 ISSN: 2321-3132 Review Article International Journal of Chemistry and Pharmaceutical Sciences www.pharmaresearchlibrary.com/ijcps Applications of Cellulases–Review Sharada.R1, Venkateswarlu.G2, Venkateswar.S3, AnandRao.M4 1Government Jr. College (G), Sangareddy, Dist. Medak, India 2Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited, R.C. Puram, Hyderabad, India 3University College of Technology, O.U., Hyderabad, India 4University College of Sciences, O.U., Hyderabad, India Received: 29 May 2014, Accepted: 30 July 2014, Published Online: 27 August 2014 Abstract Cellulases are important enzymes not only for their potential applications in different industries like industries of animal feed, agricultural, laundry & detergent, textile, paper & pulp, wine & brewery, food processing, olive oil extraction. Carotenoid extraction, pharmaceutical & medical sciences, analytical applications, protoplast production, genetic engineering and pollution treatment, but also for the significant role in bio conversion of agriculture wastes into sugar and bio ethanol. This review paper simply assesses about: Enzymes, Cellulose, Cellulases & its types, Cellulase production and detailed study on Applications of cellulases. Keywords: Enzymes, Cellulose, Cellulase. Contents 1. Introduction . 1082 2. Cellulose . 1083 3. Cellulose Applications . .1084 4. Conclusion . .. .. .1098 5. Acknowledgement . .. 1089 6. References . .. 1090 *Corresponding author Dr. Sharada Venkatesh Department of Chemistry, A.P.S.W.R.Junior College, Zaffargadh, Warangal, India Manuscript ID: IJCPS2144 PAPER-QR CODE Copyright © 2014, IJCPS All Rights Reserved 1. Introduction Enzymes are biological catalysts which are the most remarkable, highly specialized and energized protein molecules found in every cell and are necessary for life. There are over 2000 known enzymes, each of which is involved with one specific chemical reaction. -

GI Journal No. 77 1 November 30, 2015

GI Journal No. 77 1 November 30, 2015 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS JOURNAL NO.77 NOVEMBER 30, 2015 / AGRAHAYANA 09, SAKA 1936 GI Journal No. 77 2 November 30, 2015 INDEX S. No. Particulars Page No. 1 Official Notices 4 2 New G.I Application Details 5 3 Public Notice 6 4 GI Applications Guledgudd Khana - GI Application No.210 7 Udupi Sarees - GI Application No.224 16 Rajkot Patola - GI Application No.380 26 Kuthampally Dhoties & Set Mundu - GI Application No.402 37 Waghya Ghevada - GI Application No.476 47 Navapur Tur Dal - GI Application No.477 53 Vengurla Cashew - GI Application No.489 59 Lasalgaon Onion - GI Application No.491 68 Maddalam of Palakkad (Logo) - GI Application No.516 76 Brass Broidered Coconut Shell Craft of Kerala (Logo) - GI 81 Application No.517 Screw Pine Craft of Kerala (Logo) - GI Application No.518 89 6 General Information 94 7 Registration Process 96 GI Journal No. 77 3 November 30, 2015 OFFICIAL NOTICES Sub: Notice is given under Rule 41(1) of Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration & Protection) Rules, 2002. 1. As per the requirement of Rule 41(1) it is informed that the issue of Journal 77 of the Geographical Indications Journal dated 30th November 2015 / Agrahayana 09th, Saka 1936 has been made available to the public from 30th November 2015. GI Journal No. 77 4 November 30, 2015 NEW G.I APPLICATION DETAILS App.No. Geographical Indications Class Goods 530 Tulaipanji Rice 31 Agricultural 531 Gobindobhog Rice 31 Agricultural 532 Mysore Silk 24, 25 and 26 Handicraft 533 Banglar Rasogolla 30 Food Stuffs 534 Lamphun Brocade Thai Silk 24 Textiles GI Journal No. -

Textiles Under Mughals

Chapter V Textiles under Mughals- The advent of the Mughal dynasty gave an undeniable boost to production of the up-market textile, as to other craft. Textiles are singled out for mentioned by Abul Fazl, the minister and biographer of Akbar (1556-1605), in his Ain-i-Akbari, compile in the 1590‟s as a subject in which the emperor took particular interest. Akbar favoured woollen garment – the chosen wear of Sufis (Muslim mystics) – „from his indifference to everything that is worldly‟ in preference to the richer stuffs. His penchant for wool is also indicated by the steps he took to improve shawl manufacture; especially in the relation to dyes and width of fabric.1 Ain-i- Akbari goes into fascinating details on the manner of classifying garments in the imperial wardrobe (toshkhana). The textiles were arranged according to the date of entry which was recorded, sometime with other information, on a label tacked on to the piece (practice which survived in provision toshkhana into the 20th century). Price, colour and weight were also taken into account. Within these boundaries, textile took precedence according to the nature of the day, astrologically auspicious or otherwise on which they were received. A further refinement took into account the colours, of which thirty five are listed in the order of precedence. Abul Fazl further records that imperial workshops had been set up in the cities of Lahore, Agra, Fatehpur Sikri and Ahmedabad, where the best of the local craftsmen were requisitioned to supply the needs of the court.2 Persian masters were brought in to teach improved techniques. -

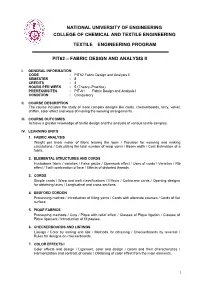

Fabric Design and Analysis Ii

NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF ENGINEERING COLLEGE OF CHEMICAL AND TEXTILE ENGINEERING TEXTILE ENGINEERING PROGRAM PIT62 – FABRIC DESIGN AND ANALYSIS II I. GENERAL INFORMATION CODE : PIT62 Fabric Design and Analysis II SEMESTER : 8 CREDITS : 3 HOURS PER WEEK : 5 (Theory–Practice) PREREQUISITES : PIT-61 Fabric Design and Analysis I CONDITION : Compulsory II. COURSE DESCRIPTION The course includes the study of more complex designs like cords, checkerboards, terry, velvet, chiffon, color effect and ways of making the weaving arrangements. III. COURSE OUTCOMES Achieve a greater knowledge of textile design and the analysis of various textile samples. IV. LEARNING UNITS 1. FABRIC ANALYSIS Weight per linear meter of fabric leaving the loom / Provision for weaving and making calculations / Calculating the total number of warp yarns / Beam width / Cost Estimation of a fabric. 2. ELEMENTAL STRUCTURES AND CORDS Huckaback fabric / varieties / False gauze / Openwork effect / Uses of cords / Varieties / Rib effect / Twill combination of lace / Effects of distorted threads. 3. CORDS Simple cords / Warp and weft classifications / Effects / Corkscrew cords / Opening designs for obtaining laces / Longitudinal and cross sections. 4. BEDFORD CORDON Processing method / Introduction of filling yarns / Cords with alternate courses / Cords of flat surface. 5. PIQUE FABRICS Processing methods / Cuts / Pique with relief effect / Classes of Pique ligation / Classes of Pique ligament / Introduction of fill passes. 6. CHECKERBOARDS AND LISTINGS Listings / Color by sorting and title / Methods for obtaining / Checkerboards by reversal / Rules for designs on checkerboards. 7. COLOR EFFECTS I Color effects and design / Ligament, color and design / colors and their characteristics / Harmonization and contrast of colors / Obtaining of color effect from the main elements. -

Hospitals for War-Wounded

hospitals_war_cover_april2003 9.6.2005 13:47 Page 1 ICRC HOSPITALS FOR WAR-WOUNDED HOSPITALS FORHOSPITALS WAR-WOUNDED This book is intended for anyone who is faced A practical guide for setting up with the task of setting up or running a hospital and running a surgical hospital which admits war-wounded. It is a practical guide in an area of armed conflict based on the experience of four nurses who have managed independent hospitals set up by the International Committee of the Red Cross. It addresses specific problems associated with setting up a hospital in a difficult and potentially dangerous environment. It provides a framework for the administration of such a hospital. It also describes a system for managing the patients from admission to discharge and includes guidelines on how to manage an influx of wounded. These guidelines represent a realistic and achievable standard of care whatever the circumstances. A practical guide 0714/002 05/2005 1000 HOSPITALS FOR WAR-WOUNDED International Committee of the Red Cross 19 Avenue de la Paix 1202 Geneva, Switzerland T +41 22 734 6001 F +41 22 733 2057 E-mail: [email protected] www.icrc.org # ICRC, April 2005, revised and updated edition This book is dedicated to the memory of Jo´n Karlsson (died in Afghanistan, 22 April 1992) Fernanda Calado Hans Elkerbout Ingebjørg Foss Nancy Malloy Gunnhild Myklebust Sheryl Thayer (died in Chechnya, 17 December 1996) HOSPITALS FOR WAR-WOUNDED A practical guide for setting up and running a surgical hospital in an area of armed conflict Jenny Hayward-Karlsson Sue Jeffery Ann Kerr Holger Schmidt INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS ISBN 2-88145-094-6 # International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva, 1998 WEB address: http://www.icrc.org CONTENTS vii CONTENTS FOREWORD ............................................ -

The Journal of the Asian Arts Society of Australia

VOLUME 17 NO. 2 JUNE 2008 the journal of the asian arts society of australia TAASA Review contents Volume 17 No.2 June 2008 3 EDITORIAL: FINDING A FOCUS TAASA REVIEW Sandra Forbes THE ASIAN ARTS SOCIETY OF AUSTRALIA INC. ABN 64093697537 • Vol. 17 No. 2, June 2008 ISSN 1037.6674 4 DEE COURT, 1944-2008: A TRIBUTE Registered by Australia Post. Publication No. NBQ 4134 Gill Green editorIAL • email: [email protected] 6 TASHI KABUM: A MUSTANG TREASURE REVEALED General editor, Josefa Green Gerry Virtue Editor this issue, Sandra Forbes publications committee 9 THOLING MONASTERY: COOPERATION AND CONSERVATION Josefa Green (convenor) • Melanie Eastburn • Sandra Rong Fan Forbes • Ann MacArthur • Jim Masselos • Ann Proctor Susan Scollay • Sabrina Snow • Christina 12 COLLECTOR’S CHOICE: A TIBETAN DRAGON CHEST Sumner design/layout Todd Sandeman Ingo Voss, VossDesign 13 COLLECTOR’S CHOICE: A MONGOLIAN YAMA printing John Fisher Printing Boris Kaspiev and Richard Price Published by The Asian Arts Society of Australia Inc. 14 TRAVELLER’S CHOICE: POLISH ART DECO IN INDIA PO Box 996 Potts Point NSW 2011 www.taasa.org.au Maria Wronska-Friend Enquiries: [email protected] 15 NEW SOUTH ASIAN GALLERY IN TORONTO TAASA Review is published quarterly and is distributed to members Haema Sivanesan of The Asian Arts Society of Australia Inc. TAASA Review welcomes submissions of articles, notes and reviews on Asian visual and performing arts. All articles are refereed. Additional copies and 16 RAFFLES AND PRAMBANAN subscription to TAASA Review are available on request. Philip Courtenay No opinion or point of view is to be construed as the opinion of The Asian Arts Society of Australia Inc., its staff, servants or agents. -

Waggle Issue 2

The Waggle Issue 2 The Waggle Magazine Issue #2. Summer/Fall 2014 The Waggle is published by an editorial collective based at Grande Prairie Regional College in Alberta, Canada. Contact us at [email protected] The online magazine is available at thewaggle.ca Managing Editor Anna Lapointe Editorial Collective Cheryl Bereziuk Kazem Mashkournia Bruce Rutley Teresa Wouters The Waggle was named by Jamie Simpson Cover design, web design, and layout John Galaugher Cover photo by René R. Gadacz Contents copyright © 2014 by the contributors. 1 The Waggle Issue 2 Table of Contents Poetry Alyssa Keil three poems Laura Hanna two poems Shannon Curley Dawn Colin James two poems Brian Sheffield two poems Annette Lapointe two poems Ashley Morford Dawn ~ Timothy Collins five poems Jim Trainer three poems Photography Evan J.M. Smith four images Fiction Robert McParland Finding Love in Bloomsdale Essays Hiroki Sato Do You Hear the Insects Sing?: Japanese Cultural Identity & Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants” Kara Witow The Rape of Wessex: Sexual Violence and Industrialization in Tess of the D’Urbervilles Travel René R. Gadacz From the Ziggurats to the Ghars: Travels in the Conflict Zones of Mesopotamia and Afghanistan, 2013 2 The Waggle Issue 2 poetry Three Poems Alyssa Keil 1. me, i’m the lipstick and synth in a jordan marsh commercial sleek black double breasted, searching for a lint roller i turned collegiate triple deckers into gangbang crackdown city streets [circa 1993) but my fear wore off; my wonder undulled I’m HERBS FOR DYES in the queens botanical garden a four year olds poking me. -

Cyclical Time and Ismaili Gnosis

ISLAMIC TEXTS AND CONTEXTS Cyclical Time General Editor Hermann Landolt and Ismaili Gnosis Professor of Islamic Studies, McGill University, Montreal and The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London Henry Corbin Assistant Editors KEGAN PAUL INTERNATIONAL London, Boston, Melbourne and Henley Elizabeth Brine in association with Dr James Morris ISLAMIC PUBLICATIONS The Institute of Ismaili Studies London The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London The Institute of Ismaili Studies was established in December 1977 with the object of promoting scholarship and learning in Islam, and a better understanding of other faiths, beliefs and practices. Its programmes are designed to encourage a balanced study of Islam and the diversity that exists within its fundamental unity. They also deal with the contemporary situation of the Islamic World, focusing on issues that are critical to its well-being. Since 1980 the Institute has been affiliated to McGill University, Mon- treal, Canada. It also works in association with other universities. With the co-operation of McGill University, the Institute runs a Depart- ment of Graduate Studies and Research (London and Paris). The series "Islamic Texts and Contexts" is edited by this Department. The views expressed in this series are those of the respective authors. Contents Editorial Note IX 1 CYCLICAL TIME IN MAZDAISM AND ISMAILISM 1 Translated by Ralph Manheim 1. Cyclical Time in Mazdaism 1 The Ages of the World in Zoroastrian Mazdaism 1 The Absolute Time of Zervanism 12 Dramaturgical Alterations 20 Time as a Personal Archetype 22 2. CyclicalTime in Ismailism 30 Absolute Time and Limited Time in the Ismaili Cosmology 30 The Periods and Cycles of Mythohistory 37 Resurrection as the Horizon of the Time of "Combat for the Angel" .