Review Body on Senior Salaries Cm 8026

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Padfield Wonders Aloud (Do Contact Me on [email protected])

University of Leeds Centre for Criminal Justice Studies Justice in the Criminal Courts in the 21st Century What are criminal courts for? Nicky Padfield wonders aloud (do contact me on [email protected]) VERY VERY DRAFT Introduction I am taking the opportunity as the first speaker at this conference to raise some big and/or broad questions. The paper is not as developed as I would like: I shall dig more into history, theory, law and practice in due course. But, in essence, my argument is that this big picture allows us to remember important principles. Many of the speakers who follow will focus on individual aspects of the trial process, often presenting original empirical research. Here I go back to basics. What is a trial? A public process which compels defendants to answer a charge of criminal wrongdoing. The outcome is often a serious sanction. Obviously, trials have to be fair. That does not simply mean they should not be unfair. Should we focus on ways in which public courts can promote fairness and justice, and indeed social cohesion? Swift justice has merits, but does not necessarily achieve just outcomes. Non-public ‗diversion‘ is equally dangerous. I will briefly raise some of the criminological literature on compliance, legitimacy and desistance – but speak up also for human rights and the rule of law - a big agenda! History For the purpose of this paper, I took as my starting point a series of riot trials, at three different moments in English history. Serendipitously, when the riots of 2011 were still recent, I happened upon a book called the Report of the Trials for Rioting at Ely and Littleport, 1816 (Warren, ed, 1997). -

Women Readers of Middle Temple Celebrating 100 Years of Women at Middle Temple the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for England and Wales

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple Middle Society Honourable the The of 2019 Issue 59 Michaelmas 2019 Issue 59 Women Readers of Middle Temple Celebrating 100 Years of Women at Middle Temple The Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for England and Wales Practice Note (Relevance of Law Reporting) [2019] ICLR 1 Catchwords — Indexing of case law — Structured taxonomy of subject matter — Identification of legal issues raised in particular cases — Legal and factual context — “Words and phrases” con- strued — Relevant legislation — European and International instruments The common law, whose origins were said to date from the reign of King Henry II, was based on the notion of a single set of laws consistently applied across the whole of England and Wales. A key element in its consistency was the principle of stare decisis, according to which decisions of the senior courts created binding precedents to be followed by courts of equal or lower status in later cases. In order to follow a precedent, the courts first needed to be aware of its existence, which in turn meant that it had to be recorded and published in some way. Reporting of cases began in the form of the Year Books, which in the 16th century gave way to the publication of cases by individual reporters, known collectively as the Nominate Reports. However, by the middle of the 19th century, the variety of reports and the variability of their quality were such as to provoke increasing criticism from senior practitioners and the judiciary. The solution proposed was the establishment of a body, backed by the Inns of Court and the Law Society, which would be responsible for the publication of accurate coverage of the decisions of senior courts in England and Wales. -

Annual Report 2012

ANNUAL REPORT For Year to 31 March 2010 ANNUAL REPORT For Year to 31 March 2012 June 2012 Judicial Studies Committee Scotland JUDICIAL STUDIES COMMITTEE COMMITTEE MEMBERS AS AT 31 MARCH 2011 LORD PRESIDENT HAMILTON (PRESIDENT OF THE JSC) THE HON LORD BRODIE (CHAIRMAN) THE HON LORD MALCOLM (VICE CHAIRMAN) SHERIFF T WELSH QC (DIRECTOR) SHERIFF A G D THORNTON (DEPUTY DIRECTOR) SHERIFF PRINCIPAL R A DUNLOP QC SHERIFF J K MITCHELL SHERIFF M J FLETCHER REV R NEILSON, VICE-CHAIRMAN OF THE JUSTICES ASSOCIATION MR A CLASPER, JUSTICE OF THE PEACE MS B CAMPBELL, DIRECTOR OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE DR J McCLURE CBE, FORMER HEAD TEACHER OF ST GEORGE’S SCHOOL FOR GIRLS COMMITTEE MEMBERS AS AT 31 MARCH 2012 LORD PRESIDENT HAMILTON (PRESIDENT OF THE JSC) (UNTIL JUNE 2012) LORD PRESIDENT GILL (PRESIDENT OF THE JSC) (FROM JUNE 2012) THE HON LORD BRODIE (CHAIRMAN) THE HON LORD MALCOLM (VICE CHAIRMAN) SHERIFF T WELSH QC (DIRECTOR) SHERIFF A J M DUFF (DEPUTY DIRECTOR) SHERIFF PRINCIPAL M STEPHEN SHERIFF L D R FOULIS SHERIFF M J FLETCHER SHERIFF I FLEMING REV R NEILSON, VICE-CHAIRMAN OF THE JUSTICES ASSOCIATION MR A CLASPER, JUSTICE OF THE PEACE MS B CAMPBELL, DIRECTOR OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE DR J McCLURE CBE, FORMER HEAD TEACHER OF ST GEORGE’S SCHOOL FOR GIRLS OFFICE STAFF DIRECTOR OF JUDICIAL STUDIES SHERIFF T. WELSH QC DEPUTY DIRECTOR SHERIFF A G D THORNTON (UNTIL JUNE 2011) SHERIFF A J M DUFF (FROM AUGUST 2011) HEAD OF EDUCATION MS J HENDERSON (FROM SEPTEMBER 2011) HEAD OF JUDICIAL STUDIES MS A FISHER SECRETARIAT LEGAL ASSISTANTS MISS A BAREKAT (UNTIL JULY 2011) MISS E JOHNSTON (UNTIL JULY 2011) MR S BALMER MR O TIDMAN (UNTIL JANUARY 2012) MISS D BOVINGDON (FROM AUGUST 2011) ADMINISTRATION MANAGER MRS L MCINTOSH (FROM JULY 2011) LAY JUSTICE CONSULTANT MRS G MAWDSLEY PERSONAL ASSISTANT TO THE MS A SHIELDS (UNTIL JUNE 2011) DIRECTOR MS J KELLY (FROM JANUARY 2012) CLERK/TYPIST MS H STEVENSON PORTER/MESSENGER MR M ORTON (UNTIL JULY 2011) CONTENTS FOREWORD 1 INDRODUCTION 6 1. -

Judicial Salaries

MINISTRY0B OF JUSTICE JUDICIAL1B SALARIES FROM 1 APRIL 2013 Group Salaries w.e.f. Salaries w.e.f. Salaries w.e.f. 01/04/11 01/04/12 01/04/13 Group 1 239,845 239,845 242,243 Lord Chief Justice Group 1.1 214,165 214,165 216,307 Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland Lord President of the Court of Session Master of the Rolls President of the Supreme Court Group 2 206,857 206,857 208,926 Chancellor of the High Court Deputy President of the Supreme Court Justices of the Supreme Court Lord Justice Clerk President of the Family Division President of the Queen’s Bench Division Senior President of Tribunals (Transitional pay) (201,613) (203,643) (207,730) Group3B 3 196,707 196,707 198,674 Inner House Judges of the Court of Session Lords Justices of Appeal Lords Justices of Appeal (N I) Group4B 4 172,753 172,753 174,481 High Court Judges [Note A] Outer House Judges of the Court of Session Puisne Judges (N I) Vice-Chancellor of the County Palatine of Lancaster Former Chief Asylum Support Adjudicator, Asylum 146,668 146,668 148,135 Support Tribunal (now judge of the First-tier Tribunal, Social Entitlement Chamber, and Deputy Judge of the Upper Tribunal) Group 5 138,548 138,548 139,933 Chairman, Scottish Land Court President of the First-tier Tribunal (Property Chamber) and Deputy Judge of the Upper Tribunal [Note L] Chief Social Security Commissioner (N I) 1 Group Salaries w.e.f. Salaries w.e.f. Salaries w.e.f. -

Joint Committee on the Emoluments of Certain Public Servants First

PP66/08 J o in t C o m m it t ee on th e E m o lu m en t s of C er t a in P u blic Ser v a n t s F ir st R epo r t fo r th e Se ssio n 2007-2008 FIRST REPORT OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE ON THE EMOLUMENTS OF CERTAIN PUBLIC SERVANTS 2007/2008 Constituted 2nd and 30th March 1965 as a Standing Joint Committee to examine the amount of expenses paid to Members and the salaries of Senior Government Officials and Crown Officers. The Keys representatives are the members of the Consultative Committee of the House. By its First Report 1992/ 93 the terms of reference were revised as follows - (i) to consider and report to the Council and Keys on - (a) the emoluments of H E Lieutenant Governor, their Honours the First and Second Deemsters and the Judge of Appeal, H M Attorney General, the High Bailiff, the Deputy High Bailiff and the Clerk of Tynwald; (b) the Tynwald Membership Pension Scheme; and (c) in addition to its consultative functions set out in paragraph (i) and as it thinks fit, the emoluments of Members of Tynwald; (ii) to carry out its consultative functions under section 6(3) of the Payments of Members’ Expenses Act 1989, as the body designated by the Payment Of Members’ Expenses (Designation of Consultative Body) Order 1989. The powers, privileges and immunities relating to the work of a committee of Tynwald are those conferred by sections 3 and 4 of the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1876, sections 1 to 4 of the Privileges of Tynwald (Publications) Act 1973 and sections 2 to 4 of the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1984. -

Michaelmas 2012

The Middle Templar The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple Issue 52 Michaelmas 2012 Middle Temple Officers 2012 Introduction Treasurer The Rt Hon The Lord Clarke of Stone-cum-Ebony After a year in post as Under Treasurer, it strikes me that two of the key qualities that Deputy Treasurer characterise Middle Temple are its open- Christopher Symons QC mindedness and its adaptability. This issue of The Middle Templar demonstrates these Deputy Treasurer Elect qualities in abundance: in 2012, the Library The Rt Hon The Lord Judge, hosted a Victorian banquet; Hall became a Lord Chief Justice theatre in the round; and Fountain Court was transformed into a Belgian Cycling Lent Reader Paradise. Like other ancient organisations – and indeed the profession Marilynne Morgan CB we represent – we will survive and thrive if we are able to adapt to face new challenges, and we have certainly shown this year that we Autumn Reader can metamorphose with the requirements of the day. Michael Crystal QC The Inn's willingness to adapt has shown itself of late not only by the Director of transformation of its physical space, but also by its ability to be self- Middle Temple Advocacy critical and open to new ways of thinking. The current review of our Derek Wood CBE QC governance, with its proposals to sharpen our focus and put greater emphasis on our core purposes, effective decision-making and Master of the Archive planning for the future, provides a good example of this. Michael Ashe QC Another prompt for serious reflection has been the sweeping review Masters of the Garden of legal education and training, currently being carried out by the legal regulators of England and Wales. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Guardian, 17 June 1999 – John Hutton, the health minister, was quoted as saying there should be ‘radical improvements in adoption services. We will not hesitate to take the necessary action in the future to ensure that looked-after children do not become the innocent victims of misplaced theory or ideology’. And a prospective adopter wrote to the Evening Standard, 4 September 2003: ‘No first-time natural parent on this planet is, or will ever be, examined and intrusively checked on their parenting capability, as adopters are.’ 2. Jenny Keating, ‘Struggle for Identity: Issues Underlying the Enactment of the 1926 Adoption of Children Act’, University of Sussex Journal of Contemporary History, issue 3 (2001), http://www.sussex.ac.uk/history/documents/3._ keating_struggle_for_identity.pdf. 3. They could apply to see their original birth certificate when they reached the age of majority but a court order was necessary. During this period very few legally adopted children would have reached the age of majority except for a few whose de facto adoptions were made official by the 1926 Adoption Act. 4. See Chapter 6. 5. Murray Ryburn, ‘Secrecy and Openness in Adoption: An Historical Perspective’, Social Policy and Administration, vol. 29, no. 2 (June 1995), pp. 151–68. 6. Ibid., op. cit., p. 166. 7. See Erica Haimes and Noel Timms, ‘Access to Birth Records and Counselling of Adopted Persons Under Section 26 of the Children Act, 1975’, Final Report to the DHSS (University of Newcastle upon Tyne, May 1983); John P. Triseliotis, ‘Obtaining Birth Certificates’, in Philip Bean (ed.), Adoption: Essays in Social Policy, Law and Sociology (London: Tavistock Publications, 1984). -

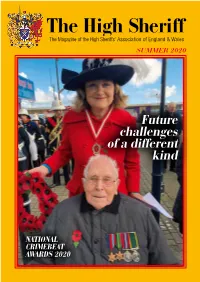

Future Challenges of a Different Kind

SUMMER 2020 Future challenges of a different kind NATIONAL CRIMEBEAT AWARDS 2020 www Lady Shrieval .antoniapugh-thom High Ant Haute dr ess Sheriffs onia for Coutur Pugh- as.co.uk eW omensw Thomas 020 ear 7731 7582 Photo courtesy of Harald Altmaier Volume 39 Issue 1 Summer 2020 The High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales President J R Avery Esq DL 12 15 Officers and Council 2020 OFFICERS Chairman The Hon H J H Tollemache Email [email protected] Honorary Secretary 34 38 J H A Williams Esq MBE Gatefield, Green Tye, Much Hadham Hertfordshire SG10 6JJ Tel 01279 842225 Email [email protected] Honorary Treasurer N R Savory Esq DL Thorpland Hall, Fakenham Norfolk NR21 0HD Tel 01328 862392 Email [email protected] COUNCIL Canon S E A Bowie DL T H Birch Reynardson Esq D C F Jones Esq DL J A T Lee Esq OBE DL Mrs V A Lloyd DL Mrs A J Parker JP DL Dr R Shah MBE JP DL Lt Col A S Tuggey CBE DL W A A Wells Esq TD (Hon Editor of The High Sheriff ) S J Young Esq MC JP DL The High Sheriff is published twice a year by Hall-McCartney Ltd for the High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales Hon Editor Andrew Wells Email [email protected] ISSN 1477-8548 ©2020 The High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales 4 From the Editor 12 General Election 44 Association regalia The Association is not as a body responsible for the opinions expressed and publications in The High Sheriff unless it is stated The ‘Red Mass’ that an article or a letter officially Diary 15 represents the Council’s views. -

The Senior Presiding Judge Has Published Guidance to the Judiciary

THE RT HON LADY JUSTICE MACUR Advocates’ Graduated Fee Scheme Dispute NOTE FROM THE SENIOR PRESIDING JUDGE 1. This guidance is issued in respect of publicly funded defence cases where the representation order was granted on or after 1 April 2018. 2. This guidance only applies to cases sent to the Crown Court during the period of the dispute between the legal profession and the Lord Chancellor. It has no wider application. 3. The aim is to ensure uniformity of approach by all judges sitting at the Crown Court and to assist defendants who appear in the Crown Court unrepresented by either counsel or solicitors. 4. There must be no suggestion that the judiciary are anything other than neutral in this dispute between the profession and the government. This guidance seeks only to address practical issues in the management of cases in the Crown Court. 5. The work of the court must continue to be listed appropriately with the expectation that those instructed to attend will do so and fulfil their commitments to their clients and the court. Any application to vacate or adjourn a case should be decided on its merits and in the interests of justice. It is important to keep an accurate factual record of the impact on the working of the court of any action, including the name and details of any cases affected. Over Arching Principles 6. The following principles apply and must govern practical steps taken by the court: Royal Courts of Justice Strand London WC2A 2LL Telephone 020 79477211 Email [email protected] Website www.judiciary.gov.uk (1) The duty of the judge is to secure a fair trial. -

Judicial Salaries from 1 April 2012

Judicial salaries from 1 April 2012 Group Salaries w.e.f. Salaries w.e.f. Salaries w.e.f. 01/04/10 01/04/11 01/04/12 Group 1 239,845 239,845 239,845 Lord Chief Justice Group 1.1 214,165 214,165 214,165 Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland Lord President of the Court of Session Master of the Rolls President of the Supreme Court Group 2 206,857 206,857 206,857 Chancellor of the High Court Deputy President of the Supreme Court Justices of the Supreme Court Lord Justice Clerk President of the Family Division President of the Queen’s Bench Division Senior President of Tribunals (Transitional pay) (199,583) (201,613) (203,643) Group 3 196,707 196,707 196,707 Inner House Judges of the Court of Session Lords Justices of Appeal Lords Justices of Appeal (N I) Group 4 172,753 172,753 172,753 High Court Judges [Note A] Outer House Judges of the Court of Session Puisne Judges (N I) Vice-Chancellor of the County Palatine of Lancaster Former Chief Asylum Support Adjudicator, Asylum 146,668 146,668 146,668 Support Tribunal (now judge of the First-tier Tribunal, Social Entitlement Chamber, and Deputy Judge of the Upper Tribunal) Group 5 138,548 138,548 138,548 Chairman, Scottish Land Court Chief Social Security Commissioner (N I) Circuit Judges at the Central Criminal Court in London (Old Bailey Judges) Vice President of the Upper Tribunal (Immigration and Asylum Chamber) President of the First-tier Tribunal (Health, Education and Social Care Chamber; Social Entitlement Chamber; General Regulatory Chamber; and Immigration and Asylum Chamber) Former Deputy President, Asylum and Immigration Tribunal Former President, Care Standards Tribunal (now judge of the First-tier Tribunal, Health, Education and Social Care Chamber, and Deputy Judge of the Upper Tribunal) 1 Group Salaries w.e.f. -

Review Body on Senior Salaries REPORT No. 73 CM 7804

Review Body on Senior Salaries REPORT No. 73 Thirty-Second Report on Senior Salaries 2010 Chairman: Bill Cockburn, CBE TD Cm 7804 £19.15 Review Body on Senior Salaries REPORT No. 73 Thirty-Second Report on Senior Salaries 2010 Chairman: Bill Cockburn, CBE TD Presented to Parliament by the Prime Minister by Command of Her Majesty March 2010 Cm 7804 £19.15 © Crown Copyright 2010 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and other departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. For any other use of this material please contact the Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU or e-mail: [email protected]. ISBN: 9780101780421 Printed in the UK by The Stationery Office Limited on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office ID P002352882 03/10 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Foreword Review Body on Senior Salaries The Review Body on Top Salaries (TSRB) was appointed in May 1971 and renamed the Review Body on Senior Salaries (SSRB) in July 1993, with revised terms of reference. The terms of reference were revised again in 1998 as a consequence of the Government’s Comprehensive Spending Review, in 2001 to allow the devolved bodies direct access to the Review Body’s advice and in 2007 to add certain NHS managers to the remit. -

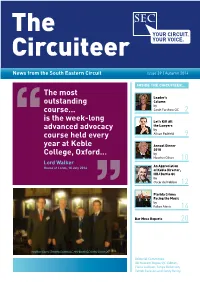

The Most Outstanding Course…

The Circuiteer News from the South Eastern Circuit Issue 39 | Autumn 2014 INSIDE THE CIRCUITEER… The most Leader’s outstanding Column by course… Sarah Forshaw QC 2 is the week-long Let’s Kill All the Lawyers advanced advocacy by course held every Alison Padfield 9 year at Keble Annual Dinner 2010 College, Oxford... by Heather Oliver 10 Lord Walker An Appreciation House of Lords, 10 July 2014 of Keble Director, HHJ Bartle QC by Oscar del Fabbro 12 Florida Crime: Facing the Music by Fallon Alexis 14 Bar Mess Reports 20 Haddon-Cave J, Timothy Dutton QC, HHJ Bartle QC & HHJ Goose QC Editorial Committee: Ali Naseem Bajwa QC (Editor), Fiona Jackson, Tanya Robinson, Tetteh Turkson and Emily Verity The Circuiteer A NOTE FROM THE EDITOR BY ALI NASEEM BAJWA QC In his final Note from the Editor American actor. No matter. Now that a British before passing over the reins to me barrister is a must-have accessory for A-list in 2008, David Wurtzel said this: “My celebrities, I have no doubt that we’ll soon successor… is, I can say, keen (essential) and snap up exclusive image rights to a similar has a track record of producing a publication event. which is more than I had.” The truth is that I’m not especially good at saying “no.” In my Having been Editor for 6 years now, it defence, a master of persuasion, David occurred to me that I had served the sort of Spens, was doing the asking. sentence usually reserved for an offence with a mid-level of seriousness which has caused David handed over a publication in the best a significant amount of harm.