Some Effects of Weather on Purple Martin Activity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hummingbirds.Pdf

Life in the Fast Lane This is MY Space! • Size: Hummingbirds are the smallest birds in • Male hummingbirds defend territories that the world! They are found only in the are rich in food sources. Americas. • To defend territories, males use warning • Feet: Hummingbirds belong to bird order sounds, flash the iridescent feathers on Apodiformes which means “without feet”: their gorget and crown, and physically hummingbirds and swifts have small, weak attack the intruder. These are feisty birds! feet and legs. They can grip and perch but Foraging for Nectar • The male’s display involves a steep climb cannot walk or turn around. upward and then rapid dive down towards • Wings: Hummingbird wings beat in a side- • Hummingbirds are mostly nectivores (eat the ground. The shape of dive is species- ways “figure 8” which allows them to fly flower nectar) but also eat any insect or specific such as Anna’s “J- shape” and forward & backward, sideways, up & down, spider it can swallow. Black-chinned’s “U-shape”. hover in place, and even upside down! • High metabolism means they need to eat a • The “pop” sound at the bottom of display • Torpor: Hummingbirds lower their body lot; hummingbirds feed every 10-15 minutes. is created by special shape of tail feathers. temperature and heart rate to conserve • Hummingbirds lap up nectar instead of It is not a vocalization. energy when there is not enough food or sucking. Capillary action moves nectar up • Female hummingbirds select territories temperatures are too cold. They reawaken in the tongue’s grooves into its mouth. with good quality nesting sites. -

Not All Sweetness and Light

CHICAGO AUDUBON SOCIETY Periodicals 5801-C N. Pulaski Road Chicago, IL 60646-6057 Navigating the world of birds and nature VOLUME 26, ISSUE 6 NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2012 very birder knows that hummingbirds involved just a single individual hummingbird, but tropical hummingbirds use to capture arthropods. Do have a symbiotic relationship with certain it is frequently cited. Robert D. Montgomerie and temperate-zone hummers use the same? wildflowers. Browse through any textbook Catherine A. Redsell tracked the foraging activities The first method, hover-gleaning, looks like nectar- about bird biology, and you will almost of a female Broad-tailed Hummingbird for two weeks E ing: the bird holds itself in the air a few inches from surely find a section detailing the connection—com- in May in and around her nest in Rose Canyon in a spider web or a leaf and reaches for the prey with plete with photographs of the birds nectaring and Arizona’s Santa Catalina Mountains. The research- bill and tongue. This may be the most easily observed diagrams of bills, tongues, stamens, pistils, and corol- ers surveyed for nectar plants in the nearby landscape of the four methods. If you witness this behavior, you las. Because they are tubular and showy, and often might try to determine the bird’s target—sometimes red, the plants gain pollinators with long memories, it’s the spider, but hummers also parasitize from the who return to the same flowers again and again. And webs, taking insects the spider has already captured. because their bills are long and their tongues flexible Not all Sweetness (And, of course, female hummers often steal the and grooved, the birds have access to energy sources threads from webs as adhesive building material for not readily available to other animals. -

Increased Understorey Causes Demise of Mixed Species Flocks at Green Wattle Creek

Mixed species flocks The Whistler 9 (2015): 63-64 Increased understorey causes demise of mixed species flocks at Green Wattle Creek Mike Newman 72 Axiom Way, Acton Park, Tasmania 7170, Australia. [email protected] I published an article titled “Mixed foraging flocks mobile honeyeaters appeared to be transient rather in a Woodville woodland” in the Hunter Bird than constant members of the group. Observers Club Newsletter October/November 1997. The article was based on observations made The third flock frequented intermediate habitat, during my monthly bird survey at Green Wattle combining open areas with some scrub Creek (32.661°S 151.649°E) on 12 July 1997 understorey. In this flock the seemingly inevitable (Newman 2009). On that date I came across three Speckled Warbler shared the understorey with separate foraging groups. Speckled Warbler White-browed Scrub-wren Sericornis frontalis and Chthonicola sagittata and Jacky Winter Microeca Silvereye Zosterops lateralis together with fairy- fascinans were conspicuous members of these wrens. Thornbills and honeyeaters, including groups and the scolding calls of the former species Lewin’s Honeyeater Meliphaga lewinii, were often drew attention to the groups. present in the lower foliage of the trees together with an immature Rose Robin Petroica rosea. My newsletter article indicated that while each of the flocks had Speckled Warblers as core The formation of these flocks was seasonal at members, there were subtle differences in the Green Wattle Creek, primarily occurring in autumn composition of the flocks, possibly as a and winter. During these seasons other species, consequence of variations in the habitat they including Spotted Pardalote Pardalotus punctatus frequented. -

Colorado Field Ornithologists the Colorado Field Ornithologists' Quarterly

Journal of the Colorado Field Ornithologists The Colorado Field Ornithologists' Quarterly VOL. 36, NO. 1 Journal of the Colorado Field Ornithologists January 2002 Vol. 36, No. 1 Journal of the Colorado Field Ornithologists January 2002 TABLE OF C ONTENTS A LETTER FROM THE E DITOR..............................................................................................2 2002 CONVENTION IN DURANGO WITH KENN KAUFMANN...................................................3 CFO BOARD MEETING MINUTES: 1 DECEMBER 2001........................................................4 TREE-NESTING HABITAT OF PURPLE MARTINS IN COLORADO.................................................6 Richard T. Reynolds, David P. Kane, and Deborah M. Finch OLIN SEWALL PETTINGILL, JR.: AN APPRECIATION...........................................................14 Paul Baicich MAMMALS IN GREAT HORNED OWL PELLETS FROM BOULDER COUNTY, COLORADO............16 Rebecca E. Marvil and Alexander Cruz UPCOMING CFO FIELD TRIPS.........................................................................................23 THE SHRIKES OF DEARING ROAD, EL PASO COUNTY, COLORADO 1993-2001....................24 Susan H. Craig RING-BILLED GULLS FEEDING ON RUSSIAN-OLIVE FRUIT...................................................32 Nicholas Komar NEWS FROM THE C OLORADO BIRD R ECORDS COMMITTEE (JANUARY 2002).........................35 Tony Leukering NEWS FROM THE FIELD: THE SUMMER 2001 REPORT (JUNE - JULY)...................................36 Christopher L. Wood and Lawrence S. Semo COLORADO F IELD O -

Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops Fuscatus)

Adaptations of An Avian Supertramp: Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops fuscatus) Chapter 6: Survival and Dispersal The pearly-eyed thrasher has a wide geographical distribution, obtains regional and local abundance, and undergoes morphological plasticity on islands, especially at different elevations. It readily adapts to diverse habitats in noncompetitive situations. Its status as an avian supertramp becomes even more evident when one considers its proficiency in dispersing to and colonizing small, often sparsely The pearly-eye is a inhabited islands and disturbed habitats. long-lived species, Although rare in nature, an additional attribute of a supertramp would be a even for a tropical protracted lifetime once colonists become established. The pearly-eye possesses passerine. such an attribute. It is a long-lived species, even for a tropical passerine. This chapter treats adult thrasher survival, longevity, short- and long-range natal dispersal of the young, including the intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics of natal dispersers, and a comparison of the field techniques used in monitoring the spatiotemporal aspects of dispersal, e.g., observations, biotelemetry, and banding. Rounding out the chapter are some of the inherent and ecological factors influencing immature thrashers’ survival and dispersal, e.g., preferred habitat, diet, season, ectoparasites, and the effects of two major hurricanes, which resulted in food shortages following both disturbances. Annual Survival Rates (Rain-Forest Population) In the early 1990s, the tenet that tropical birds survive much longer than their north temperate counterparts, many of which are migratory, came into question (Karr et al. 1990). Whether or not the dogma can survive, however, awaits further empirical evidence from additional studies. -

Observations of Mixed-Species Bird Flocks at Kichwa Tembo Camp, Kenya

Observations of mixed-species bird flocks at Kichwa Tembo Camp, Kenya Alasdair I V Gordon and Nancy M Harrison Alasdair I V Gordon Anglia Ruskin University East Road Cambridge CB1 1PT UK e-mail: [email protected] Corresponding author and contact details: Nancy M Harrison Anglia Ruskin University East Road Cambridge CB1 1PT UK e-mail: [email protected] Telephone: 0845 196 2524 1 Abstract Mixed-species foraging flocks were studied at Kichwa Tembo Camp on the edge the Masia Mara National Reserve in Kenya between July and September 2004. Observations were made on 29 mixed-species flocks, in which 24 species participated. African Paradise Flycatcher Terpsiphone viridis , Black-backed Puffback Dryoscopus cubla , Grey-backed Cameroptera Camaroptera brachyura , Collard Sunbird Hedydipna collaris and Cabanis’s Greenbul Phyllastrephus cabanisi were the most common participants in mixed-species flocks, as well as among the most frequently encountered bird species overall. The Black-backed Puffback was identified as the nuclear species in flocks due to their abundance and frequency with which they were followed by other species. Mixed-species flocks represent another niche dimension in this diverse bird community, but few of these species could be described as flock specialists; most of the birds observed in mixed-species flocks in this study were opportunistic attendant species, including the African Pygmy Kingfisher Ispidina picta, not previously described as joining mixed-species flocks. 2 Introduction Mixed-species flocks of insectivorous birds are a conspicuous feature of tropical communities worldwide (Rand 1954, Moynihan 1960, Jones 1977, Powell 1979, Wiley 1980), important in structuring avian communities of African forests (Chapin 1932, Vernon 1980), but also evident in open woodland and savannah habitats (Greig- Smith 1978a, Thomson and Ferguson 2007). -

![Western Australian ]Ournal of Conservation and Land](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2391/western-australian-ournal-of-conservation-and-land-1762391.webp)

Western Australian ]Ournal of Conservation and Land

SC WESTERNAUSTRALIAN The avifauna of the forestsof south-westWestern Australia: changesin speciescomposition, distdbution, ]OURNAL OF CONSERVATION and abundancefollowing anthropogenicdisturbance AND LAND MANAGEMENT IAN ABBOTT PACE 1 Summary PAGE 2 Introduction Methods PACE 13 q^o.ia(.^nmonrrrw PAGE 52 Discovery and taxonomy of species PAGE 54 Biogeography PAGE 60 Habitats occupied PAGE 61 Abundance PAGE 62 Repncductivecapaciry nesting zone, and nesting substrate PAGE 65 Foraging niche PAGE 66 Population movements PACE 67 Disturbance ecology PAGE 85 Pressingunanswered questions PAGE 87 Acknowledgements References PAGE 104 Appendix PAGE 105 Tables PAGE 175 Notes on Author PACE 176 llstructionsto Authors 136 D.J. Cale et al. Corrigenda Abbott, I. (1999). The avifauna of the forests of southwest Western Australia: Changes in species composition, distribution and abundance following anthropogenic disturbance. CALMScience Supplement No. 55, 1-175. The following corrections should be noted: TEXT PAGE COLUMN LINE ACTION 2 2 4-5* Delete reference to Keartland collecting in forests in 1895 near King George Sound 6 1 31** Change ?1905 to 1907 6 1 32** Change ?1906 to 1907 31 1 18** Change Figure 3 to Figure 4 44 2 20* Change Storr 199 to Storr 1991 67 1 13* Change 1829 to 1830 97 2 5* Change Zoologishe to Zoologische * counting from bottom of page, ** from top TABLES PAGE ACTION 140 The rows Leipoa ocellata, Coturnix novaezelandiae and Coturnix ypsilophora are out of sequence. Place them after Dromaius novaehollandiae, as is the case elsewhere in -

Birds and Caves at Lava Beds National Monument

Birds and Caves at Lava Beds National Monument Overview Grade Level: 3rd-8th (O.S.S 3rd-5th & 7th) (C.S.S: 3rd-7th) Students learn how the caves at Lava Beds NM Learner Objectives formed and the animals that use the caves. SSStudent will: • Learn how the caves at Lava Beds National Monument formed California Science • Standards Investigate the different animals that use the caves as habitat Grade 3: 3.b.c.d.-L.S. • Interpret data and practice journaling skills. Grade 4: 3.b.-L.S. Grade 7: 7.c.-I&E Background Information LLL Oregon Science ava Beds National Monument sits on the northern slope of the largest (by Standards surface area and volume) volcano in the Cascade Mountains: Medicine Lake Grade 3: 3.S.2 Volcano. There are over 700 known lava tubes and caves within the Grade 4: 2L.1 monument that were formed by eruptions from Medicine Lake Volcano. As Grade 5: 3S.2 Grade 7: 3S.3 lava flows down the mountain sides, the outer layer of the flow cools rapidly forming a hard outer shell insulating the lava within it. When the eruption National Standards stops, the remaining lava drains away leaving behind hollow tubes. The Content Standard A: cooling lava shrinks and cracks forming “skylights” and collapses create Science as Inquiry entrances to the caves where light and animals can enter. Content Standard C: Life Sciences The caves and tubes at Lava Beds National Monument provide a habitat for Materials Included several different species of birds, mammals, invertebrates and plants. All of Student Journal the biota (all living things found in an area) that use caves can be classified Laminated species into three groups: troglobite, troglophile, and trogloxene. -

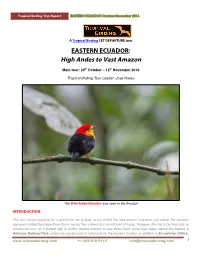

High Andes to Vast Amazon

Tropical Birding Trip Report EASTERN ECUADOR October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN ECUADOR: High Andes to Vast Amazon Main tour: 29th October – 12th November 2016 Tropical Birding Tour Leader: Jose Illanes This Wire-tailed Manakin was seen in the Amazon INTRODUCTION: This was always going to be a special for me to lead, as we visited the area where I was born and raised, the Amazon, and even visited the lodge there that is run by the community I am still part of today. However, this trip is far from only an Amazonian tour, as it started high in Andes (before making its way down there some days later), above the treeline at Antisana National Park, where we saw Ecuador’s national bird, the Andean Condor, in addition to Ecuadorian Hillstar, 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report EASTERN ECUADOR October-November 2016 Carunculated Caracara, Black-faced Ibis, Silvery Grebe, and Giant Hummingbird. Staying high up in the paramo grasslands that dominate above the treeline, we visited the Papallacta area, which led us to different high elevation species, like Giant Conebill, Tawny Antpitta, Many-striped Canastero, Blue-mantled Thornbill, Viridian Metaltail, Scarlet-bellied Mountain-Tanager, and Andean Tit-Spinetail. Our lodging area, Guango, was also productive, with White-capped Dipper, Torrent Duck, Buff-breasted Mountain Tanager, Slaty Brushfinch, Chestnut-crowned Antpitta, as well as hummingbirds like, Long-tailed Sylph, Tourmaline Sunangel, Glowing Puffleg, and the odd- looking Sword-billed Hummingbird. Having covered these high elevation, temperate sites, we then drove to another lodge (San Isidro) downslope in subtropical forest lower down. -

Strategies of American Redstarts and Least Flycatchers in a Northern Hardwoods Forest

COMPETITIVE INTERACTIONS AND ADAPTIVE STRATEGIES OF AMERICAN REDSTARTS AND LEAST FLYCATCHERS IN A NORTHERN HARDWOODS FOREST THOMAS W. SHERRY • Departmentof BiologicalSciences, Dartmouth College,Hanover, New Hampshire03755 USA ABSTRACT.--Eeologiealinteractions between American Redstarts (Setophagaruticilla) and LeastFlycatchers (Empidonax minimus) were studiedin the Hubbard Brook ExperimentalForest, New Hampshire, USA during three breeding seasons.These two taxonomieallydistinct pas- serineshave convergedon the ecologicalniche of "flycatching,"overlapping significantly in body size,bill morphology,foraging behavior, and in patternsof habitat exploitation.They exhibita striking amount of interspecificaggression during the breedingperiod. Coexistencebetween the two speciesis mediatedby subtlehabitat preferencesand reinforcedby interspecificaggression and by differencesin life history characteristics.The redstart is a broad-niehed,behaviorally plastic, sociallysubordinate habitat generalistrelative to the flycatcher. It also fledgesyoung earlier and defendslarger territories.Such differencesin socialdominance and in niche breadths amongmembers of an ecologicalguild may be importantin permittingcertain constellations of speciesto coexistand thereforeimportant organizingfeatures of bird communitystructure. Re- ceived 10 May 1978, accepted6 December 1978. THE bestevidence for the existenceof interspecificcompetition is often geographic in nature (MacArthur 1972). Dramatic intrageneric phenomena, such as abrupt speciesreplacements, character -

Attracting Birds in Ohio

TABLE OF CONTENTS Attracting Birds . 1 Food . 2 Feeder Types . 2 Peanut Butter or Suet-filled Log . 2 Metal Guard . 2 Single-sided Hopper Feeder . 3 Suet Box . 3 Tray Feeder . 4 Double-sided Hopper Feeding Station . 4 Food Types . 5 Feeder Cleanliness . 6 When to Feed . 6 Predators at Your Feeding Station . 7 Squirrels and Raccoons . 7 Habitat . 8 Natural Food . 8 Shelter . 9 Birdhouse Dimensions and Placement . 10 Purple Martin House . 11 Tree Swallow House Plans . 12 Bluebird House Plans . 12 Small Forest Bird House . 13 Roosting Shelter . 13 Mourning Dove Nest Structure . 14 Nest Shelf for Robins and Phoebes . 14 Unroofed Shelf for use Under Protective Hanging . 14 Wood Duck Nest Box . 15 Wren Houses . 16 American Kestrel or Screech Owl Nesting Box . 16 Predator Guards . 17 General Care and Maintenance . 19 Water . 20 In Summary . 21 ATTRACTING BIRDS Birds are everywhere around us. We see them in our backyards, as we drive along our streets and highways, and even where we work and play. Birds captivate us for many reasons – probably the most obvious is because of their beautiful songs. The flute-like melody of the wood thrush is soothing; the robin singing in February gives us hope of spring. Second to their varied calls are their bright colors—consider the brilliance of the scarlet tanager or the “electric yellow” goldfinch. The drab camouflage of other species is equally intriguing like the near invisible nighthawk roosting on a tree branch. Further, the speed of some (swallows and swifts) and grace (a heron silently wading) of others; or the power and maneuverability of a Cooper’s hawk chasing a sparrow through the backyard are more reasons to be in awe of these feathered creatures. -

British Columbia Waterfowl Society Summer 2017 British Columbia Waterfowl Society

BRITISH COLUMBIA ® WATERFOWL SOCIETY ® 5191 Robertson Road, Delta, British Columbia V4K 3N2 40924050 PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO 40924050 RETURN UNDELIVERABLE CANADIAN ADDRESSES TO CIRCULATION DEPT. 330 - 123 MAIN STREET TORONTO ON M5W 1A1 email: [email protected] Trumpeter Swan © Dennis Nelson BRITISH COLUMBIA WATERFOWL SOCIETY SUMMER 2017 BRITISH COLUMBIA WATERFOWL SOCIETY Managers of the George C. Reifel Migratory Bird Sanctuary Since 1963 - dedicated to the conservation and study of migratory waterfowl- Marshnotes: Executive: President: Jack Bates Editor: Kathleen Fry Vice President: George C. Reifel Treasurer: James A. Morrison The contents of Marshnotes may not be reprinted Secretary: Barney W. Reifel without written permission of the Editor. Jack Bates Circulation: 2,700. Directors: F. Wayne Diakow Published four times a year. Kevin Husband James A. Morrison The British Columbia Waterfowl Society, Gerald S. Oyen 5191 Robertson Road, Douglas B. Ransome Delta, British Columbia Barney W. Reifel V4K 3N2 George C. Reifel Liam Reifel Telephone: 604 946 6980 Kenneth I. Thompson Facsimile: 604 946 6982 Website: www.reifelbirdsanctuary.com Committee Chairs: Email: [email protected] Building/ Grounds: Barney W. Reifel Community Relations: George C. Reifel Submissions, articles, photographs and letters for Interpretation/Education: F. Wayne Diakow publication may be sent to the above email and postal Outreach: George C. Reifel addresses marked for attention of Marshnotes Editor. Please include your telephone number and the Editor will contact you. Staff: Sanctuary Manager: Kathleen Fry Gift Shop Manager: Varri Raffan DEADLINE FOR THE NEXT ISSUE Reception: Susan Norris OF MARSHNOTES Biologist: Dan Dixon Maintenance: David McClue October 15th, 2017 Hours of Operation: 9:00 a.m.