PED ESSA Outreach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rio Rancho High School 301 Loma Colorado St Ne Rio Rancho, NM 87124-6562 School Phone: 505-962-9501 Home Phone: Fax: 505-896-5903 [email protected]

Rio Rancho High School 301 Loma Colorado St Ne Rio Rancho, NM 87124-6562 School Phone: 505-962-9501 Home Phone: Fax: 505-896-5903 [email protected] Superintendent Principal Vice Principal Athletic Director Dr. V. Sue Cleveland Sherri Carver Ryan Kettler Vince Metzgar Varsity Volleyball (Girls) 2016-2017 Day Date Opponent Place Time Friday Aug. 26 @ El Paso Tournament - Day 1 El Paso, TX TBA Saturday Aug. 27 @ El Paso Tournament - Day 2 El Paso, TX TBA Tuesday Sep. 06 St. Pius X HS Rio Rancho High School 6:30PM Wednesday Sep. 07 @ APS Metro Tourney - Day 1 TBA TBA Friday Sep. 09 @ APS Metro Tourney - Day 2 TBA TBA Saturday Sep. 10 @ APS Metro Tourney - Day 3 TBA TBA Tuesday Sep. 13 Sandia High School Rio Rancho High School 6:30PM Tuesday Sep. 20 @ Miyamura High School Miyamura High School 6:30PM Friday Sep. 23 Rio Rancho Volleybash-Day 1 Rio Rancho High School TBA Saturday Sep. 24 Rio Rancho Volleybash-Day 2 Rio Rancho High School TBA Tuesday Sep. 27 * @ Cleveland High School Cleveland High School 6:30PM Wednesday Sep. 28 * Volcano Vista High School Rio Rancho High School 6:30PM Friday Oct. 07 * @ Cibola High School Cibola High School 6:30PM Tuesday Oct. 11 * Cleveland High School Rio Rancho High School 6:30PM Saturday Oct. 15 * Piedra Vista High School Rio Rancho High School 6:30PM Thursday Oct. 20 * @ Volcano Vista High School Volcano Vista High School 6:30PM Thursday Oct. 27 * Cibola High School Rio Rancho High School 6:30PM Friday Oct. 28 * @ Piedra Vista High School Piedra Vista High School 6:30PM 05/24/2016 * = League Event Report generated by Schedule Star 800-822-9433 . -

Date of Meet Name of Meet Location of Meet Host School Contact

Date of Meet Name of Meet Location of Meet Host School Contact Person Contact Email for Meet 4/17/2021 Angelo DiPaolo Memorial Track Meet Thoreau High School Miyamura High School Peterson Chee [email protected] 4/17/2021 Early Bird Distance Meet Wool Bowl Roswell High School Tim Fuller [email protected] 4/21/2021 Sandia Prep Quad 1 Sandia Prep Sandia Prep Willie Owens [email protected] 4/22/2021 St. Pius Distance Fest @ UNM Tailwind Meet UNM St. Pius X / UNM Jeff Turcotte [email protected] 4/23/2021 Bulldog Relays Artesia Artesia High School Matt Conn [email protected] 4/23/2021 Ralph Bowyer Invitational Carlsbad Carlsbad High School Kent Hitchens [email protected] 4/23/2021 Los Lunas High School Los Lunas High School Los Lunas High School Wilson Holland [email protected] 4/23/2021 Onate Invitational Field of Dreams, Las Cruces Onate High School David Nunez [email protected] 4/23/2021 Golden Spike Classic Santa Fe High School Santa Fe High School Peter Graham [email protected] OR [email protected] 4/23/2021 Rock Nation Relays Shiprock High School Track Shiprock High School Alice Kinlichee [email protected] 4/23/2021 Thoreau Hawks Invite Thoreau, NM Thoreau High School DeJong DeGroat or Lawrence Sena [email protected] 4/24/2021 Bobcat Invitational Bobcat Stadium Bloomfield High School Robert Griego [email protected] 4/24/2021 Farmington Invite Farmington High School Farmington High School Jeff Dalton [email protected] 4/24/2021 Gadsden Invite Santa Teresa High School Gadsden High School Karen -

Title: the Distribution of an Illustrated Timeline Wall Chart and Teacher's Guide of 20Fh Century Physics

REPORT NSF GRANT #PHY-98143318 Title: The Distribution of an Illustrated Timeline Wall Chart and Teacher’s Guide of 20fhCentury Physics DOE Patent Clearance Granted December 26,2000 Principal Investigator, Brian Schwartz, The American Physical Society 1 Physics Ellipse College Park, MD 20740 301-209-3223 [email protected] BACKGROUND The American Physi a1 Society s part of its centennial celebration in March of 1999 decided to develop a timeline wall chart on the history of 20thcentury physics. This resulted in eleven consecutive posters, which when mounted side by side, create a %foot mural. The timeline exhibits and describes the millstones of physics in images and words. The timeline functions as a chronology, a work of art, a permanent open textbook, and a gigantic photo album covering a hundred years in the life of the community of physicists and the existence of the American Physical Society . Each of the eleven posters begins with a brief essay that places a major scientific achievement of the decade in its historical context. Large portraits of the essays’ subjects include youthful photographs of Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, and Richard Feynman among others, to help put a face on science. Below the essays, a total of over 130 individual discoveries and inventions, explained in dated text boxes with accompanying images, form the backbone of the timeline. For ease of comprehension, this wealth of material is organized into five color- coded story lines the stretch horizontally across the hundred years of the 20th century. The five story lines are: Cosmic Scale, relate the story of astrophysics and cosmology; Human Scale, refers to the physics of the more familiar distances from the global to the microscopic; Atomic Scale, focuses on the submicroscopic This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. -

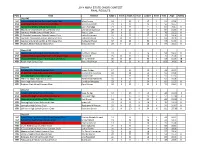

P I E D R a V I S T a I N V I T a T I O N

3/24/13 Piedra Vista Invitational- Complete Results - MileSplit New Mexico RaceTab Meet Manager Online registration for your meet MileSplit Affiliate :: High School :: College :: Canada :: Running Camps :: Explore the Network You are not logged in. Register or Login. Like 16 Follow 118 followers Home Sttatte Records Coverage Sttatts Viideo News Callendar Teams Diiscussiion Resources enter search term Search P I E D R A V I S T A I N V I T A T I O N A L March 23, 2013 @ Piedra Vista HS Track in Farmington, NM Hosted by Piedra Vista High School Registration Closed View Your Entries Back to Piedra Vista Invitational Licensed to Farmington High School -NM HY-TEK's Meet Manager 3/23/2013 08:44 PM Piedra Vista Invitational 2013 - 3/23/2013 Results Girls 100 Meter Dash ========================================================================== Name Year School Finals H# Points ========================================================================== Finals 1 Flores, Zhianna Piedra Vista 12.95 4 7 2 Tanner, Madilyn Piedra Vista 13.43 4 5 3 Hess, River Farmington H 13.66 4 4 4 Ford, Lachelle Farmington H 13.73 4 2.50 4 Foutz, Shantel Kirtland Cen 13.73 4 2.50 6 Martinez, Sierra Aztec High S 13.77 4 1 7 Newland, Rikki Aztec High S 13.96 3 8 Schultz, Ashley Farmington H 14.10 5 8 Gabehart, Tyra Aztec High S 14.10 4 10 Depauli, Natalie Hershey Miya 14.16 9 11 Waukazoo, Muriel Navajo Prep 14.40 6 12 Roach, Amy Bayfield Hig 14.60 1 13 Schulder, Ashlyn Bayfield Hig 14.64 9 14 Fox, SheRrae Gallup High 14.66 9 15 Valdez, Azia Aztec High S 14.68 2 16 -

School District School Name Alamogordo School

SCHOOL DISTRICT SCHOOL NAME ALAMOGORDO SCHOOL DISTRICT 1 ACADEMY DEL SOL ALAMOGORDO HIGH SCHOOL BUENA VISTA ELEMENTARY SCHOOL CHAPARRAL MIDDLE SCHOOL HEIGHTS ELEMENTARY SCHOOL HIGH ROLLS MT PARK ELEM SCHOOL HOLLOMAN INTERMEDIATE SCHOOL HOLLOMAN MIDDLE SCHOOL HOLLOMAN PRIMARY SCHOOL LA LUZ ELEMENTARY SCHOOL MOUNTAIN VIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL NORTH ELEMENTARY SCHOOL OREGON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL SACRAMENTO ELEMENTARY SCHOOL SIERRA ELEMENTARY SCHOOL YUCCA ELEMENTARY SCHOOL ALBUQUERQUE SCHOOL DISTRICT A MONTOYA ELEMENTARY SCHOOL ACADEMIA DE LENGUA Y CULTURA ACADEMY OF TRADES & TECHNOLOGY ACCESS ALTERNATIVE HIGH SCHOOL ACOMA ELEMENTARY SCHOOL ADOBE ACRES ELEMENTARY SCHOOL ALAMEDA ELEMENTARY SCHOOL ALAMOSA ELEMENTARY SCHOOL ALBUQUERQUE HIGH SCHOOL ALBUQUERQUE INST-MATH & SCI ALVARADO ELEMENTARY SCHOOL AMY BIEHL CHARTER HIGH SCHOOL APACHE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL ARMIJO ELEMENTARY SCHOOL ARROYO DEL OSO ELEM SCHOOL ATRISCO ELEMENTARY SCHOOL ATRISCO HERITAGE ACADEMY BANDELIER ELEMENTARY SCHOOL BARCELONA ELEMENTARY SCHOOL BEL-AIR ELEMENTARY SCHOOL BELLEHAVEN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL CAREER ACADEMIC TECHNICAL ACAD CAREER ENRICHMENT CENTER 1 CARLOS REY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL CESAR CHAVEZ COMMUNITY SCHOOL CHAMIZA ELEMENTARY SCHOOL CHAPARRAL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL CHELWOOD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL CHRISTINE DUNCAN CMTY SCH CIBOLA HIGH SCHOOL CLEVELAND MIDDLE SCHOOL COCHITI ELEMENTARY SCHOOL COLLET PARK ELEMENTARY SCHOOL COMANCHE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL CORRALES INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL CREATIVE EDUC PREP INST 1 CREATIVE EDUC PREP INST 2 DEL NORTE HIGH SCHOOL DENNIS CHAVEZ ELEM SCHOOL DESERT RIDGE MIDDLE -

2018 Nmaa State Choir Contest Final Results

2018 NMAA STATE CHOIR CONTEST FINAL RESULTS Place Choir Director Judge 1 Score Judge 2 Score Judge 3 Score Total Avge. Rating Class MS 1ST Lincoln Middle School Advanced Treble Choir Mika Proctor 19 I 15 I 17 I 51 17.00 I 2ND Eisenhower Middle School Concert Choir William Gonzales 21 II 16 I 19 I 56 18.67 I 3RD Los Alamos Middle School Hawk Choir Jason Rutledge 21 II 24 II 17 I 62 20.67 II 4TH Mountain View Middle School Mixed Choir Johnathan Davidson 28 II 19 I 17 I 64 21.33 II 5TH Hermosa Middle School Mixed Choir Petra J. Lyon 20 II 25 II 25 II 70 23.33 II 6TH El Dorado Community School Concert Choir Galen Prenevost 23 II 22 II 27 II 72 24.00 II 7TH Gonzales Community School Advanced Choir Judy Rotenberg 35 III 22 II 27 II 84 28.00 II 8TH Capitan Middle School 6th & 7th Grade Choir DuWayne Shaver 37 III 26 II 30 II 93 31.00 II 9TH Tibbetts Middle School Mixed Choir Shera Jemmett 26 II 27 II 44 III 97 32.33 II Class A-3A 1ST Capitan High School 8th-12th Grade Choir DuWayne Shaver 18 I 21 II 19 I 58 19.33 II 2ND Cloudcroft Municipal Schools 8th-12th Grade Choir Pat Gaskill 35 III 22 II 18 I 75 25.00 II 3RD Victory Christian School - The Sounds of Victory Mr. Lyle Miller 35 III 23 II 35 III 93 31.00 III 4TH Raton High School Choir Kerry Hutchinson 36 III 31 III 35 III 102 34.00 III Class 4A 1ST Portales High School Chamber Choir James Golden 17 I 14 I 15 I 46 15.33 I 2ND St. -

Chief Manuelito Scholars of 2020

The Office of Navajo Nation Scholarship & Financial Assistance Proudly Presents Chief Manuelito Scholars of 2020 Alexis Atcitty Aiyana Austin Kelly Becenti Amber Begay Elijah Adam Begay Kimball Jared Begay Erin Begaye Natalie Bigman Marissa Bowens Skyridge High School; Brigham Bloomfield High School Tuba City High School Farmington High School Newcomb High School Mountain View High School Middle College High School Marcos De Niza High School Grayson High School Young University Stanford University Northern Arizona University University of Denver Northern Arizona University Brigham Young University Northern Arizona University Fort Lewis College Brigham Young University Aric Bradley Colin Patrick Brown Naat’anii Castillo Triston Charles Cameron Charleston Di’Zhon Chase Kiley Chischilly Ayden Clytus Coule Dale Tuba City High School Middle College High School McClintock High School Piedra Vista High School Shiprock High School Miyamura High School Window Rock High School Skyline High School Farmington High School Northern Arizona University Northern Arizona University Northwestern University Colorado Mesa University Northland College Arizona State University Arizona State University Arizona State University Capital University Brooke Damon Grace Dewyer Brianna Dinae Etsitty Jaylin Ray Farrell Mia D. Freeland Victor Gallegos Madyson Deale Julian Brent Deering Laciana E. Desjardins Flagstaff High School Farmington High School Flagstaff High School Mesquite High School Cactus High School Marcos De Niza High School Greyhills Academy High School Albuquerque High School Page High School Northern Arizona University Stanford University Arizona State University Louisiana State University Duke University Arizona State University Northern Arizona University University of Redlands Stanford University Amaya Garnenez Valerie Kay Gee ShanDiin Yazhi Manina Gopher Ryan J. Grevsmuehl John J. -

Team Schedule Softball

Team Schedule Los Lunas High School Wilson Holland Girls Softball 1776 Emilio Lopez Rd NW School Phone: 505-865-4646 2/3/2020 to 5/24/2020 Los Lunas, NM 87031 Fax: 505-865-6022 [email protected] Softball Girls Varsity Place Time Saturday 02/29/20 Centennial HS (Double Header) Home 11:00 AM Saturday 02/29/20 Centennial HS (Double Header) Home 1:00 PM Tuesday 03/03/20 Volcano Vista Away 4:00 PM Thursday 03/05/20 Las Cruces HS Away 5:00 PM Tuesday 03/10/20 Miyamura High School Home 4:00 PM Thursday 03/12/20 Manzano High School Home 4:00 PM Tuesday 03/17/20 Los Alamos High School Away 4:00 PM Friday 03/20/20 Artesia High Sch. (Artesia Invite March 20-21) Away TBA Tuesday 03/24/20 La Cueva High School Away 4:00 PM Thursday 03/26/20 Rio Rancho High School (Rio Rancho Invite Away TBA March 26-28) Tuesday 03/31/20 Eldorado High Sch. Home 4:00 PM Thursday 04/02/20 Belen High Sch. Away 6:00 PM Tuesday 04/07/20 St. Pius High School Home 4:00 PM Thursday 04/09/20 Grants High Sch. Away 6:00 PM Tuesday 04/14/20 Valencia High School Home 6:00 PM Tuesday 04/21/20 Belen High Sch. Home 6:00 PM Thursday 04/23/20 St. Pius High School Away 4:00 PM Tuesday 04/28/20 Grants High Sch. Home 6:00 PM Thursday 04/30/20 Valencia High School Away 6:00 PM Friday 05/08/20 OPEN DATE (1st round May 8-9) Away TBA Thursday 05/14/20 OPEN DATE (5A State Softball Championships Away TBA May 14-16) Girls JV Place Time Tuesday 03/03/20 Volcano Vista Home 4:00 PM Tuesday 03/10/20 Cleveland High School Away 4:00 PM Thursday 03/12/20 Manzano High School Away 4:00 PM Friday 03/13/20 Piedra Vista High School (PIEDRA VISTA Away TBA INVITE MARCH 13-14) Tuesday 03/17/20 Los Alamos High School Away 4:00 PM Tuesday 03/24/20 La Cueva High School Home 4:00 PM Tuesday 03/31/20 Eldorado High Sch. -

2018 State Concert Band Schedule Draft

STATE CONCERT BAND CONTEST PERFORMANCE SCHEDULE April 20-21, 2018 ~ V. Sue Cleveland High School (Rio Rancho, NM) Day Warm-Up Performance Class School Friday, 4/20/18 9:55 AM 10:20 AM 4A St. Michael's High School 7th-12th Grade Concert Band Friday, 4/20/18 10:20 AM 10:45 AM A-3A Rehoboth Christian School Band Friday, 4/20/18 10:45 AM 11:10 AM A-3A Tucumcari High School 7th-12th Grade Band Friday, 4/20/18 11:10 AM 11:35 AM A-3A Capitan Schools 8th-12th Grade Concert Band Friday, 4/20/18 11:35 AM 12:00 PM A-3A Cloudcroft Municipal Schools 7th-12th Grade Band Friday, 4/20/18 12:00 PM 12:25 PM A-3A Cimarron High School Wind Ensemble Friday, 4/20/18 1:15 PM 1:45 PM 5A Alamogordo High School Wind Ensemble Friday, 4/20/18 1:45 PM 2:15 PM 5A Los Alamos High School Wind Ensemble Friday, 4/20/18 2:15 PM 2:45 PM 5A Grants High School Concert Band Friday, 4/20/18 2:45 PM 3:15 PM 5A Deming High School Symphonic Band Friday, 4/20/18 3:15 PM 3:45 PM 5A Artesia High School Concert Band Friday, 4/20/18 3:45 PM 4:15 PM 5A Chaparral High School Wind Ensemble Friday, 4/20/18 4:30 PM 5:00 PM 6A Santa Fe High School Wind Ensemble Friday, 4/20/18 5:00 PM 5:30 PM 6A Manzano High School Wind Ensemble Friday, 4/20/18 5:30 PM 6:00 PM 6A Piedra Vista High School Concert Band Friday, 4/20/18 6:00 PM 6:30 PM 6A Clovis High School Wind Symphony Friday, 4/20/18 6:30 PM 7:00 PM 6A Volcano Vista High School Symponic Band Friday, 4/20/18 7:00 PM 7:30 PM 6A V. -

Page 1 NEW MEXICO STATE HIGH SCHOOL XC CHAMPIONSHIPS

Page 1 NEW MEXICO STATE HIGH SCHOOL XC CHAMPIONSHIPS RIO RANCHO, NM - NOVEMBER 6, 2010 OVERALL INDIVIDUAL RESULTS: ALL GIRLS Place Name Class School 1mile 2mile Finish Pace Bib# ===== ======================= ===== ========================= ======== ======== ======== ===== ===== 1 Julia Foster 4A Albuquerque Academy 5:45 12:09 18:35.80 6:00 264 2 Caroline Lewiecki 5A Manzano 6:11 12:42 18:56.50 6:06 368 3 Jenna Thurman 4A Del Norte 5:56 12:17 19:06.40 6:09 278 4 Malia Gonzales 5A Cleveland 12:42 19:09.85 6:11 326 5 Kate Norskog 3A St. Michael's High School 6:03 12:27 19:21.55 6:14 174 6 Nisa Rascon 4A Valencia 6:06 12:43 19:28.65 6:17 290 7 Jordan Grace 5A La Cueva 6:11 12:41 19:36.45 6:19 359 8 Caroline Kaufman 1-2A East Mountain 5:59 12:41 19:39.85 6:20 16 9 Marissa Nathe 4A St. Pius 6:17 12:57 19:43.45 6:21 269 10 Leanne Lee 3A Zuni 6:01 12:45 19:47.05 6:23 121 11 Tamara Lementino 5A Rio Rancho 6:11 12:45 19:57.45 6:26 340 12 Kimberly Chapman 5A Cibola 6:11 12:51 19:58.30 6:26 347 13 Anna Wermer 4A Los Alamos High School 6:17 13:05 20:02.45 6:28 226 14 Natalie Gorman 5A Eldorado 6:15 13:15 20:05.80 6:29 351 15 Teresa Sandoval 4A Los Alamos High School 6:11 13:03 20:09.40 6:30 225 16 Beth Wright 5A Albuquerque High 6:11 12:52 20:09.55 6:30 419 17 Brittany Collins 5A Clovis 6:22 13:16 20:11.00 6:30 404 18 Autumnrain Chee 3A Shiprock 6:12 13:04 20:11.85 6:31 111 19 Anna Olesinski 4A Roswell High 5:58 12:51 20:12.00 6:31 314 20 Coley Norcross 5A Eldorado 13:10 20:12.25 6:31 355 21 Myka Curtis 4A Kirtland Central High Sch 6:10 13:08 20:13.15 -

The Meeting Was Called to Order by Mr. Bruce Carver at 9:00 Am

NMAA Commission Meeting May 18, 2016 9:00 AM NMAA Office Welcome – The meeting was called to order by Mr. Bruce Carver at 9:00 am. A roll call was conducted by Mrs. Mindy Ioane and the following members were present: Mr. Bruce Carver (Large, Area A) Mr. Dickie Roybal (Small, Area B) Mr. Dale Fullerton (Large, Area B) Mr. Gary Schuster (Small, Area C) Mr. Ernie Viramontes (Large, Area C) Mr. Dave Campbell (Small, Area D) Ms. Nickie McCarty (Large, Area D) Mr. Pete MacFarlane (Non-Public School Rep.) Mr. Cooper Henderson (New Mexico High School Athletic Directors Association Rep.) Mr. Jess Martinez (New Mexico Officials Association Rep.) Mr. Thomas Mabrey (New Mexico High School Coaches Association Rep.) Mr. Don Gerheart (Activities Council Member) via teleconference Ms. Debbie Coffman (Jr. High/Middle School Rep.) Not present: Mr. Todd Kurth (Small, Area A) Ms. Jennifer Viramontes (State School Boards Association Representative) Mr. Scott Affentranger (National Association of Secondary School Principals Rep.) 13 members present representing a quorum. Approval of Agenda: Mr. Carver asked for a motion to approve the agenda. Mr. Schuster made the motion to approve the agenda. Mr. Gerheart seconded the motion. A vote was taken and passed unanimously (13-0). Approval of Minutes: Mr. Carver asked for a motion to approve the minutes of the February 3, 2016 Commission Meeting as presented. Mr. Fullerton made a motion to approve the minutes. Mr. MacFarlane seconded the motion. A vote was taken and passed unanimously (13-0). NMAA Directors’ Report: Mr. Dusty Young, NMAA Associate Director, discussed four (4) items on his report: 1) the success of the four winter and five spring State Championships, announcing that attendance numbers were higher than last year; 2) the NMAA Foundation recently awarded 16 scholarships to graduating seniors from 15 NMAA member schools in the amount of $23,000. -

2016-2017 School Directory

DEPARTMENT of DINÉ EDUCATION Complied by: Office of Diné Accountability & Compliance P.O. Box 670 Window Rock, Arizona 86515-0670 (928) 871-7466 www.navajonaondode.org TABLE OF CONTENTS I. NAVAJO BUREAU-OPERATED SCHOOLS: Education Resource Centers – Window Rock. 03 II. HOPI EDUCATION LINE OFFICE. .06 III. SACRAMENTO EDUCATION LINE OFFICE: . 07 IV. TRIBALLY CONTROLLED SCHOOLS: . 08 Public Law 93-638: (1) Contract School Public Law 100-297: (31) Grant Schools Arizona / New Mexico / Utah V. TRIBALLY CONTROLLED SCHOOLS. 12 Public Law 100-297: (1) Grant School New Mexico South (Southern Pueblo Agency) VI. NAVAJO NATION HEADSTART: . .13 VII. ARIZONA PUBLIC SCHOOLS: . 14 VIII. NEW MEXICO PUBLIC SCHOOLS: . .21 IX. UTAH PUBLIC SCHOOLS: . .29 X. ARIZONA PRIVATE SCHOOLS: . 32 XI. NEW MEXICO PRIVATE SCHOOLS: . .33 XII. SCHOOL BOARD ORGANIZATIONS: . .34 2 Navajo Bureau-Operated Schools PHONE FAX Dr. Tamarah Pfeiffer, Associate Deputy Director Navajo 928 / 871-5932 928 / 871-5945 United States Department of the Interior /5961 BUREAU OF INDIAN EDUCATION Education Resource Center- Window Rock Old Club Building 3, PO Box 1449 Window Rock, Arizona 86515-1449 [email protected] Education Resource Center – Window Rock PRINCIPAL PHONE FAX Bread Springs School K-3 Nancy Taranto 505 / 778-5665 778-5692 P.O. Box 1117 Gallup, New Mexico 87305-1117 ChiChilTah/Jones Ranch School K-8 Marlene Tsosie 505 / 778-5574 778-5575 P.O. Box 278 Vanderwagon, New Mexico 87326-0278 Crystal Boarding School K-6 Alberto Castruita 505 / 777-2385 777-2648 P.O. Box 1288 Navajo, New Mexico 87328 Pine Springs Day School K-4 Lou Ann Jones 928 / 871-4311 871-4341 P.O.