Iran's Economy Is Stagnating Even Before

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Court of Justice Confirms the Annulment of the Fund-Freezing Measures in Place Against Bank Mellat Since 2010

Court of Justice of the European Union PRESS RELEASE No 14/16 Luxembourg, 18 February 2016 Judgment in Case C-176/13 P Press and Information Council v Bank Mellat The Court of Justice confirms the annulment of the fund-freezing measures in place against Bank Mellat since 2010 The Council failed to provide sufficient grounds or evidence In order to strengthen efforts to combat Iran’s nuclear proliferation-sensitive activities and the development of nuclear weapon delivery systems in Iran, the Council froze the funds of various Iranian financial entities, including Bank Mellat, 1 from 2010 onwards. The reasons given for freezing Bank Mellat’s funds were essentially as follows: ‘Bank Mellat engages in a pattern of conduct which supports and facilitates Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile programmes. It has provided banking services to United Nations and EU listed entities or to entities acting on their behalf or at their direction, or to entities owned or controlled by them. It is the parent bank of First East Export [FEE] which is designated under United Nations Security Council Resolution 1929’. Bank Mellat successfully challenged the freezing of its funds before the General Court.2 The Council subsequently appealed to the Court of Justice to have the General Court’s judgment set aside. In today’s judgment, the Court of Justice, confirming the principles established in Kadi II,3 finds, as did the General Court, that the first two sentences of the reasons set out above do not enable Bank Mellat to establish specifically which banking services it provided to which entities, particularly as the persons whose accounts were managed by Bank Mellat are not identified. -

Iran Chamber of Commerce,Industries and Mines Date : 2008/01/26 Page: 1

Iran Chamber Of Commerce,Industries And Mines Date : 2008/01/26 Page: 1 Activity type: Exports , State : Tehran Membership Id. No.: 11020060 Surname: LAHOUTI Name: MEHDI Head Office Address: .No. 4, Badamchi Alley, Before Galoubandak, W. 15th Khordad Ave, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: 1191755161 Email Address: [email protected] Phone: 55623672 Mobile: Fax: Telex: Membership Id. No.: 11020741 Surname: DASHTI DARIAN Name: MORTEZA Head Office Address: .No. 114, After Sepid Morgh, Vavan Rd., Qom Old Rd, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: Email Address: Phone: 0229-2545671 Mobile: Fax: 0229-2546246 Telex: Membership Id. No.: 11021019 Surname: JOURABCHI Name: MAHMOUD Head Office Address: No. 64-65, Saray-e-Park, Kababiha Alley, Bazar, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: Email Address: Phone: 5639291 Mobile: Fax: 5611821 Telex: Membership Id. No.: 11021259 Surname: MEHRDADI GARGARI Name: EBRAHIM Head Office Address: 2nd Fl., No. 62 & 63, Rohani Now Sarai, Bazar, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: 14611/15768 Email Address: [email protected] Phone: 55633085 Mobile: Fax: Telex: Membership Id. No.: 11022224 Surname: ZARAY Name: JAVAD Head Office Address: .2nd Fl., No. 20 , 21, Park Sarai., Kababiha Alley., Abbas Abad Bazar, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: Email Address: Phone: 5602486 Mobile: Fax: Telex: Iran Chamber Of Commerce,Industries And Mines Center (Computer Unit) Iran Chamber Of Commerce,Industries And Mines Date : 2008/01/26 Page: 2 Activity type: Exports , State : Tehran Membership Id. No.: 11023291 Surname: SABBER Name: AHMAD Head Office Address: No. 56 , Beside Saray-e-Khorram, Abbasabad Bazaar, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: Email Address: Phone: 5631373 Mobile: Fax: Telex: Membership Id. No.: 11023731 Surname: HOSSEINJANI Name: EBRAHIM Head Office Address: .No. -

Annual Report Bank Mellat Turkey 2016

ANNUAL REPORT BANK MELLAT TURKEY 2016 BANK MELLAT, HEADQUARTERS: TEHRAN – IRAN, TURKEY HEAD OFFICE IN ISTANBUL, BRANCH OFFICES IN ANKARA AND IZMIR 2016 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS I. GENERAL PRINCIPLES WITH RESPECT TO THE ANNUAL REPORT II. CONTENTS OF THE ANNUAL REPORT A. Introduction 1. Summary Financial Information 2. Historical Development of the Branch 3. Shareholding Structure of the Branch 4. Changes in its Capital and Shareholding Structure During the Operating Period 5. Titles of Natural or Legal Persons who hold Qualified Shares and Information about Their Shares 6. Remarks Regarding the Shares, if any, Held by the Chairman and Members of the Board of Managers and General Manager and Deputy General Managers of the Branch 7. Remarks on the Operating Period made by the Chairman of the Board of Managers and General Manager and Their Prospects 7.1. Message of the Chairman of the Board of Directors 7.2. General Manager’s Message 8. Remarks Regarding the Staff, Number of Branches, Branch Service Type, Scope of Activities and Position in the Sector B. Information about the Management and Corporate Governance Practices 1. Board of Managers 2. Senior Management 3. Information About the Operations Conducted Pursuant to the Provisions of the Regulation on the Internal Systems of Banks and the Department Managers Regarding Internal Systems 4. Other Committees 5. Information Regarding Human Resources Practices 6. Information about the transactions with the risk group in which the branch is included 6.1. Information about the credits extended to the risk group in which the branch is included 6.2. Information about deposit accounts owned by the risk group in which the branch is included 6.3. -

Annual Report Annual Report

Tehran Stock Exchange Annual Report Exchange 2011 Stock Tehran Tehran Stock Exchange Address: No.228,Hafez Ave. Tehran - Iran Tel: (+98 021) 66704130 - 66700309 - 66700219 Fax: (+98 021) 66702524 Zip Code: 1138964161 Gun-metal relief discovered in Lorestan prov- ince, among the Achaemedian dynasty’s (550-330 BC)Antiquities. Featuring four men, hand in hands, indicating unity and cooperation; standing inside circles of 2011 globe,which is it, according to Iranian ancient myths, put on the back of two cows, ANNUAL symbols of intelligence and prosperity. Tehran Stock Exchange Implementation: CAPITAL&MARKET REPORT ANNUAL REPORT Tehran Stock Exchange 2011 Tehran Stock Exchange Tehran www.tse.ir Annual Report 2011 2 Tehran Stock Exchange Tehran www.tse.ir Mission Statement To develop a fair, efficient and transparent market equipped with diversified instruments and easy access in order to create added value for the stakeholders. Vision To be the region’s leading Exchange and country’s economic growth driver. Goals To increase the capital market’s share in financing the economic productive activities. To apply the effective rules and procedures to protect the market’s integrity and shareholders’ equity. To expand the market through using updated and efficient technology and processes. To promote financial literacy and develop investing and shareholding culture in Iran. To extend and facilitate the market access through information technology. To create value for shareholders and comply with transparency and accountability principles, with cooperation -

Off- Campus Branches; Education at IUST

Iran University of Science and Technology Department of Electrical Engineering Off-Campus Branches Arak Branch Behshahr Branch 124 Iran University of Science and Technology Off-Campus Branches IUST Arak Branch activities. The information center of Arak Branch is giving 24 hour services to the users as one of the best information networks in the area and the city. IUST Arak Branch was founded in 1992. Located in the center Most noteworthy educational/research achievements of the of the city of Arak, was established to provide training for skilled IUST Arak Branch within the past four years include: personnel and reinforce a close relation between Arak industrial Publication of 25 journal papers in highly accredited pole and the IUST, dealing with the research necessities of local engineering journals at national and international levels. industries. Presentation of more than 200 conference papers in Its graduates have shown remarkable success, either as scientific and engineering gatherings. industry employees or as student pursuing their postgraduate Authorship and translation of 6 titles of books in the field of studies in recognized universities. This newly established faculty Technical & Engineering. has had an important role in research activities in the area and Recipient of selected inventor of the country in 2007. excellent cooperation with local industries and government. Recipient of selected researcher of the province in years of IUST Arak Branch transfers the experiences of the industries 2006 and 2007. into classrooms by making some cooperation contracts with Recipient of 3 patents. main industries in the area. 28 industrial project contracts with the Municipality and All faculty members are committed to higher educational and Jahad Keshavarzi. -

BIC Statement CORRESPONDENT BANK's NAME ALL BR. COUNTRY

BIC Statement CORRESPONDENT BANK'S NAME ALL BR. COUNTRY 1 AFABAFKA ARIAN BANK,KABUL 2005/11/30 AFGHANISTAN 2 BKMTAM22 EUR BANK MELLAT CJSC YEREVAN, YEREVAN ARMENIA 3 OBKLAT2L OBERBANK AG, LINZ AUSTRIA 4 GIBAATWW ERSTE BANK DER OESTERREICHISCHEN SPARKASSEN AG, VIENNA AUSTRIA 5 SCHOATWW SCHOELLERBANK AG,VIENNA 2005/05/05 AUSTRIA 6 BKAUATWW EUR UNICREDIT BANK AUSTRIA AG, VIENNA(Bank Austria) 2009/02/17 AUSTRIA 7 CAPNAZ22 AZERBAIJAN INDUSTRY BANK JSC, BAKU 2007/10/02 AZERBAIJAN 8 MELIAZ22 BANK MELLI IRAN, BAKU BRANCH, BAKU 2005/04/20 AZERBAIJAN 9 ABCOBHBM ARAB BANKING CORPORATION (B.S.C.), MANAMA BAHRAIN 10 BMEABHBM BAHRAIN MIDDLE EAST BANK B.S.C.,MANAMA 2010/07/14 BAHRAIN 11 FUBBBHBM EUR,AED FUTURE BANK (B.S.C.) C , MANAMA 2005/12/04 BAHRAIN 12 GULFBHBM GULF INTERNATIONAL BANK, MANAMA BAHRAIN 13 SCBLBDDX STANDARD CHARTERED BANK, DHAKA BANGLADESH 14 SBINBDDH STATE BANK OF INDIA, DHAKA 2006/07/10 BANGLADESH 15 BCBLBDDH BANGLADESH COMMERCE BANK BANGLADESH 16 AKBBBY2X BELARUSBANK , MINSK 2009/02/17 BELARUS 17 BELBBY2X BELVNESHECONOMBANK OJSC , MINSK 2005/05/05 BELARUS 18 HNRBBY2X HONOR BANK,MINSK 2010/07/14 BELARUS 19 BPSBBY2X JSC BPS-BANK (FORMERLY BELPROMSTROIBANK), MINSK 2007/10/02 BELARUS 20 BBTKBY2X TC BANK , MINSK 2009/09/29 BELARUS 21 FBHLBE22 CREDIT EUROPE BANK N.V. ANTWERP BRANCH , ANTWERPEN 2008/02/07 BELGIUM 22 BYBBBEBB BYBLOS BANK EUROPE S.A., BRUSSELS BELGIUM (ALL BR.IN 23 GEBABEBB FORTIS BANK S.A./N.V. BRUSSELS, BRUSSELS BELGIUM) BELGIUM (ALL WORLD 24 KREDBEBB KBC BANK NV , BRUSSELS BR.) BELGIUM 25 DEUTBRSP DEUTSCHE BANK S.A. -

In the Name of God 4

IN THE NAME OF GOD 4. 50th Anniversary of Iran Capital Market 6. TSE at a glance 11. TSE Annual General Assembly 14. Board of Directors 16.Message from board of directors 18. Time line 25. Introduction to TSE and financial performance 30. Financial performance 33. Market Operations Review 54. Corporate Governance 58. Risk Analysis Report 63. Operations & Achievements in the Financial Year TEHRAN STOCK EXCHANGE 67. TSE’s strategic plans 68. Targets & plans in 2017 - 2018 Annual Report 72. Financial Statements Fiscal Year Ended 20 March 2017 CONTENTS 2 TSE ANNUAL REPORT STOCK EXCHANGE HISTORY IN IRAN DATES BACK TO MORE THAN YEARS NOW February 1967 is the first registered date when introducing electronic trading system, restructuring Tehran Stock Exchange was inaugurated with 6 listed of the capital market and demutualizing of TSE, companies. Later some public bonds and certain privatization of the state-owned companies, joining state-backed securities were added to the tradable global capital markets’ entities, deregulation of foreign instruments. investment and developing new securities, like ETFs and derivatives. In its initial period of development (1967-1978), TSE became the trading venue, as well as fund raising With huge resources, vast geographical area, large platform for 105 listed companies, including 22 population and great untapped opportunities, banks, 2 insurance companies, and 81 other industrial Iran’s capital market is a real promising investment corporations. destination for local and international investors. th In the next periods of evolution, several significant The new logo on the other page has been designed 50 Anniversary of milestones can be specified at the Exchange, namely to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the capital providing tax incentives for listing and trading in TSE, market in Iran. -

FIN-2010-A008 Issued: June 22, 2010 Subject: Update on the Continuing Illicit Finance Threat Emanating from Iran

Advisory FIN-2010-A008 Issued: June 22, 2010 Subject: Update on the Continuing Illicit Finance Threat Emanating from Iran The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) is issuing this advisory to supplement information previously provided on the serious threat of money laundering, terrorism finance, and proliferation finance emanating from the Islamic Republic of Iran,1 and to provide guidance to financial institutions regarding United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1929, adopted on June 9, 2010. UNSCR 1929 contains a number of new provisions which build upon and expand the financial sanctions imposed in previous resolutions (UNSCRs 1737, 1747, and 1803) and which are designed to prevent Iran from abusing the international financial system to facilitate its illicit conduct. The resolution’s measures include a call for States, in addition to implementing their obligations pursuant to resolutions 1737, 1747, 1803, and 1929, to prevent the provision of any financial service – including insurance and reinsurance – or asset that does or could contribute to Iran’s proliferation activities; and to prohibit on their territories new relationships with Iranian banks, including the opening of any new branches of Iranian banks, if there is a suspected link to proliferation. The UNSCR also requires States to ensure their nationals exercise vigilance when doing business with any Iranian firm, including the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and the Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines (IRISL), when there is a possibility that -

UK HMT: Financial Sanctions Against Iran

Financial Sanctions Notification 27/07/2010 Iran Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 668/2010 1. This notification is issued in respect of the financial measures taken against Iran. 2. Her Majesty’s Treasury issue this notification to advise that, with the publication of Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 668/2010 of 26 July 2010 (‘Regulation 668/2010’) in the Official Journal of the European Union, (O.J. L195, 27.7.2010, P25) on 27 July 2010, the Council of the European Union has again amended Annex V to Council Regulation (EU) No. 423/2007 (‘Regulation 423/2007’). 3. Article 7(2) of Regulation 423/2007 provides for the Council to identify persons, not designated by the United Nations Security Council or by the Sanctions Committee established pursuant to paragraph 18 of UNSCR 1737 (2006), as subject to the financial sanctions imposed by Regulation 423/2007. Such persons are listed in Annex V to Regulation 423/2007. 4. The amendments made to Annex V by Regulation 668/2010 take the form of the addition of individuals and entities to the list of those subject to the financial sanctions imposed by Regulation 423/2007. Article 7 of Regulation 423/2007 imposes an asset freeze on these individuals and entities. 5. With effect from 27 July 2010, all funds and economic resources belonging to, owned, held or controlled by persons in Annex V to Regulation 423/2007 as amended by the Annex to Regulation 668/2010 must be frozen. No funds or economic resources are to be made available, directly or indirectly, to or for the benefit of persons listed in Annex V unless authorised by the Treasury. -

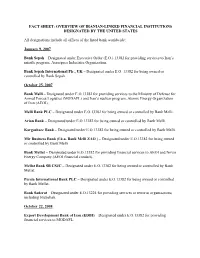

FACT SHEET: OVERVIEW of IRANIAN-LINKED FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS DESIGNATED by the UNITED STATES All Designations Include All Offic

FACT SHEET: OVERVIEW OF IRANIAN-LINKED FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS DESIGNATED BY THE UNITED STATES All designations include all offices of the listed bank worldwide: January 9, 2007 Bank Sepah – Designated under Executive Order (E.O.) 13382 for providing services to Iran’s missile program, Aerospace Industries Organization. Bank Sepah International Plc., UK – Designated under E.O. 13382 for being owned or controlled by Bank Sepah. October 25, 2007 Bank Melli – Designated under E.O.13382 for providing services to the Ministry of Defense for Armed Forces Logistics (MODAFL) and Iran’s nuclear program, Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI). Melli Bank PLC – Designated under E.O.13382 for being owned or controlled by Bank Melli. Arian Bank – Designated under E.O.13382 for being owned or controlled by Bank Melli. Kargoshaee Bank – Designated under E.O.13382 for being owned or controlled by Bank Melli. Mir Business Bank (f.k.a. Bank Melli ZAO ) – Designated under E.O.13382 for being owned or controlled by Bank Melli. Bank Mellat – Designated under E.O.13382 for providing financial services to AEOI and Novin Energy Company (AEOI financial conduit). Mellat Bank SB CSJC – Designated under E.O.13382 for being owned or controlled by Bank Mellat. Persia International Bank PLC – Designated under E.O.13382 for being owned or controlled by Bank Mellat. Bank Saderat – Designated under E.O.13224 for providing services to terrorist organizations, including Hizballah. October 22, 2008 Export Development Bank of Iran (EDBI) – Designated under E.O.13382 for providing financial services to MODAFL. Banco Internacional de Desarrollo – Designated under E.O.13382 for being owned or controlled by EDBI. -

FIN-2008-A002 Issued: March 20, 2008 Subject: Guidance to Financial Institutions on the Continuing Money Laundering Threat Involving Illicit Iranian Activity

Advisory FIN-2008-A002 Issued: March 20, 2008 Subject: Guidance to Financial Institutions on the Continuing Money Laundering Threat Involving Illicit Iranian Activity The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) is issuing this advisory to supplement information previously provided1 on serious deficiencies present in the anti-money laundering systems of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) stated in October 2007 that Iran’s lack of a comprehensive anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) regime represents a significant vulnerability in the international financial system. In response to the FATF statement, Iran passed its first AML law in February 2008. The FATF, however, reiterated its concern about continuing deficiencies in Iran’s AML/CFT system in a statement on February 28, 2008. Further, on March 3, 2008, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 1803 (UNSCR 1803), calling on all states to exercise vigilance over activities of financial institutions in their territories with all banks domiciled in Iran and their branches and subsidiaries abroad. The FATF statement, combined with the UN’s specific call for vigilance, illustrates the increasing risk to the international financial system posed by the Iranian financial sector, including the Central Bank of Iran. Iran’s AML/CFT deficiencies are exacerbated by the Government of Iran’s continued attempts to conduct prohibited proliferation related activity and terrorist financing. Through state-owned banks, the Government of Iran disguises its involvement in proliferation and terrorism activities through an array of deceptive practices specifically designed to evade detection. The Central Bank of Iran and Iranian commercial banks have requested that their names be removed from global transactions in order to make it more difficult for intermediary financial institutions to determine the true parties in the transaction. -

Annual Report Bank Mellat Turkey 2020

ANNUAL REPORT BANK MELLAT TURKEY 2020 BANK MELLAT, HEAD OFFICE: TEHRAN, IRAN, ISTANBUL, TURKEY HQ, ANKARA AND IZMIR BRANCHES 2020 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS I. GENERAL PRINCIPLES WITH RESPECT TO THE ANNUAL REPORT II. CONTENTS OF THE ANNUAL REPORT A. Introduction 1. Summary Financial Information 2. Historical Development of the Branch 3. Shareholding Structure of the Branch 4. Changes in its Capital and Shareholding Structure During the Operating Period 5. Titles of Natural or Legal Persons who hold Qualified Shares and Information about Their Shares 6. Remarks Regarding the Shares, if any, Held by the Chairman and Members of the Board of Managers and General Manager and Deputy General Managers of the Branch 7. Remarks on the Operating Period made by the Chairman of the Board of Managers and General Manager and Their Prospects 8. Remarks Regarding the Staff, Number of Branches, Branch Service Type, Scope of Activities and Position in the Sector B. Information about the Management and Corporate Governance Practices 1. Board of Directors 2. Senior Management 3. Information About the Operations Conducted Pursuant to the Provisions of the Regulation on the Internal Systems of Banks and the Department Managers Regarding Internal Systems 4. Other Committees 5. Information Regarding the Practices Human Resources 6. Information about the transactions with the risk group in which the branch is included 6.1. Information about the credits extended to the risk group in which the branch is included 6.2. Information about deposit accounts owned by the risk group in which the branch is included 6.3. Information about the loans borrowed from the risk group in which the branch is included 6.4.