2. a Profile of Rural Poverty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ministerul Cultelor Și Instrucțiunii Publice. 1947-1949

ARHIVELE NAŢIONALE SERVICIUL ARHIVE NAŢIONALE ISTORICE CENTRALE Biroul Arhive Administrative şi Culturale Nr. inventar: 3435 INVENTAR MINISTERUL CULTELOR ŞI INSTRUCŢIUNII PUBLICE 1947 - 1949 2017 PREFAȚĂ Perioada anilor 1947-1949 marchează transformările produse în sistemul educațional românesc, când a fost instalat modelul sovietic. Astfel, prin Decretul nr. 175 din 3 august 1948, în școlile din România a fost impus sistemul manualului unic, la început fiind traduse manualele rusești, controlul fiind făcut prin Comisia de Învățământ a Direcției de Agitație și Propagandă a Comitetului Central al P.M.R., condusă de Mihail Roller. Reformele din anul 1949 au fost esențiale în distrugerea sistemului vechi și crearea unei noi versiuni, școlile fiind segmentate pe trei niveluri (grupuri școlare, școli și universități de mijloc), care ofereau o educație identică, multe din universități fiind retrogradate la nivelul de institute tehnice, iar școlile private și religioase au fost închise și au fost preluate de către stat. Limba rusă a devenit obligatorie, iar ateismul științific a luat locul religiei, cenzura a devenit foarte răspândită, mulți autori clasici fiind interziși. Cu toate acestea, au existat și unele realizări, cea mai importantă fiind campania de alfabetizare, dar și reintroducerea învățământului în limbile minorităților. Inventarul Ministerul Cultelor și Instrucțiunii Publice (1947-1949) conţine următoarele genuri de documente: decizii, rapoarte, instrucțiuni, proiecte legi, decrete, HCM, circulare, corespondenţă externă, programe, -

Pubblicazione Di Una Domanda Di Modifica Del Disciplinare Di Un Nome Del Settore Vitivinicolo Di Cui All'articolo 105 Del Rego

C 93/68 IT Gazzetta uff iciale dell’Unione europea 19.3.2021 Pubblicazione di una domanda di modifica del disciplinare di un nome del settore vitivinicolo di cui all’articolo 105 del regolamento (UE) n. 1308/2013 del Parlamento europeo e del Consiglio (2021/C 93/09) La presente pubblicazione conferisce il diritto di opporsi alla domanda di registrazione ai sensi dell’articolo 98 del regolamento (UE) n. 1308/2013 del Parlamento europeo e del Consiglio (1) entro due mesi dalla data della presente pubblicazione. DOMANDA DI MODIFICA DEL DISCIPLINARE DI PRODUZIONE «Iaşi» PDO-RO-A0139-AM01 Data di presentazione della domanda: 12.12.2014 1. Norme applicabili alla modifica Articolo 105 del regolamento (UE) n. 1308/2013 – modifica non minore 2. Descrizione e motivi della modifica 2.1. Estensione della zona delimitata della denominazione d’origine, che amplia la zona di produzione Descrizione e motivazioni Nella contea di Iași esistono zone delimitate coltivate a vite situate nei comuni di Probota, Țigănași, Andrieșeni, Bivolari, Trifești e Roșcani, a breve distanza, ossia 10 o 40 km a est, sud-est e nord-est, del comune di Iași, che fa parte della zona delimitata della DOP Iași. Queste località presentano condizioni agronomiche e climatiche identiche a quelle della zona di Iași, dove si producono i vini di qualità Iași DOP. Per questo motivo devono essere incluse nella zona della DOP Iași affinché i loro vigneti possano produrre vino con le caratteristiche tipiche e autentiche delle parcelle della zona di produzione della DOP Iași. L’area delimitata completa e precisa sarà: Sottodenominazione Copou: — Città di Iași, distretto di Copou; — Comune di Aroneanu, villaggi di Aroneanu, Șorogari, Aldei e Dorobanț; — Comune di Rediu, villaggi di Rediu, Breazu, Tăutești e Horlești; — Comune di Movileni, villaggi di Movileni, Potângeni e Iepureni. -

Investeşte În Oameni!

Investeşte în oameni! PROGRAMUL DE FORMARE CONTINUĂ PROIECTUL „COMPETENŢE CHEIE TIC ÎN CURRICULUMUL ŞCOLAR” Repartitia pe grupe la informatică Centrul de formare - Colegiul Economic ”M. Kogălniceanu” Focșani Formator - Ciubotaru Bogdan Nr. Numele şi prenumele Scoala Crt. 1. Tenea Ovidiu Ernest Scoala cu cls I-VIII nr. 2 Marasesti 2. Măciucă Marius Liceul Pedagogic “Spiru Haret” Focşani 3. Ionescu Cristina Şcoala cu cls I-VIII „Anghel Saligny” 4. Țîțu Ion Colegiul National „Alexandru Ioan Cuza” 5. Stanila Daniela Grupul Scolar ”Grigore Gheba” Dumitrești 6. Grigore Andreea-Alina Şcoala cu cls. I-VIII Homocea 7. Pavăl Laura Școala ”Ion Basgan” 8. Dima Lenuţa Școala ”Ion Basgan” 9. Dumitru Violeta Școala ”Mareșal Averescu” Adjud 10. Stroie Marcel Școala ”D. Zamfirescu” Focșani 11. Grecu Daniel Valentin Scoala cu clasele I-VIII Slobozia Bradului 12. Colin Liliana Colegiul Naţional „Unirea” 13. Vulpoiu Genovica Colegiul Naţional „Unirea” 14. Neşu Liliana Colegiul Naţional „Unirea” 15. Onea Emil Colegiul Naţional „Unirea” 1/14 Investeşte în oameni! PROGRAMUL DE FORMARE CONTINUĂ PROIECTUL „COMPETENŢE CHEIE TIC ÎN CURRICULUMUL ŞCOLAR” Repartitia pe grupe limba și literatura română Centrul de formare - CCD ”S. Mehedinți” Vrancea Formator – Silvia Chelariu Grupa 1 Nr. Numele şi prenumele Scoala Crt. 1. Opait Anca Scoala cu cls I-VIII nr. 2 Marasesti 2. Catrinoiu Maricica Scoala cu cls I-VIII Dimitrie Gusti Nereju 3. Nistoroiu Luminita Scoala cu cls I-VIII Dimitrie Gusti Nereju 4. Stanciu Ionela Scoala cu cls I-VIII ,,Mihail Armencea’’ Adjud 5. Severin Florentina Scoala cu cls I-VIII ,,Mihail Armencea’’ Adjud 6. Novac Maricica Scoala cu cls I-VIII Paunesti 7. Marcu Nicoleta Scoala cu cls I-VIII Paunesti 8. -

JUDEȚ UAT NUMAR SECȚIE INSTITUȚIE Adresa Secției De

NUMAR JUDEȚ UAT INSTITUȚIE Adresa secției de votare SECȚIE JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 1 Directia Silvică Vrancea Directia Silvică Vrancea Strada Aurora ; Nr. 5 JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 2 Teatrul Municipal Focşani Teatrul Municipal Focşani Strada Republicii ; Nr. 71 Biblioteca Judeţeană "Duiliu Zamfirescu" Strada Mihail JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 3 Biblioteca Judeţeană Duiliu Zamfirescu"" Kogălniceanu ; Nr. 12 Biblioteca Judeţeană "Duiliu Zamfirescu" Strada Nicolae JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 4 Biblioteca Judeţeană Duiliu Zamfirescu"" Titulescu ; Nr. 12 Şcoala "Ştefan cel Mare" - intrarea principală Strada JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 5 Şcoala Ştefan cel Mare" - intrarea principală" Ştefan cel Mare ; Nr. 12 Şcoala "Ştefan cel Mare" - intrarea elevilor Strada Ştefan JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 6 Şcoala Ştefan cel Mare" - intrarea elevilor" cel Mare ; Nr. 12 Şcoala "Ştefan cel Mare" - intrarea secundara Strada JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 7 Şcoala Ştefan cel Mare" - intrarea secundara" Ştefan cel Mare ; Nr. 12 JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 8 Colegiul Tehnic Traian Vuia"" Colegiul "Tehnic Traian Vuia" Strada Coteşti ; Nr. 52 JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 9 Colegiul Tehnic Traian Vuia"" Colegiul "Tehnic Traian Vuia" Strada Coteşti ; Nr. 52 Poliţia Municipiului Focşani Strada Prof. Gheorghe JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 10 Poliţia Municipiului Focşani Longinescu ; Nr. 33 Poliţia Municipiului Focşani Strada Prof. Gheorghe JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 11 Poliţia Municipiului Focşani Longinescu ; Nr. 33 Colegiul Economic "Mihail Kogălniceanu" Bulevardul JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 12 Colegiul Economic Mihail Kogălniceanu"" Gării( Bulevardul Marx Karl) ; Nr. 25 Colegiul Economic "Mihail Kogălniceanu" Bulevardul JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 13 Colegiul Economic Mihail Kogălniceanu"" Gării( Bulevardul Marx Karl) ; Nr. 25 JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 14 Şcoala Gimnazială nr. -

SITUAȚIA Centralizatoare a Operatorilor Economici Care Exploatează Spații De Depozitare Autorizate Direcţia Pentru Agricultu

MINISTERUL AGRICULTURII ŞI DEZVOLTĂRII RURALE Direcţia pentru Agricultură Iaşi IAŞI, B-dul Ştefan cel Mare şi Sfânt, nr. 47-49, cod poştal – 700064 Tel. 0232/255958, 0232/255957; 0232/211012 E-mail: [email protected]; Site: www.dadris.ro Nr. 635 din 15.04.2013 SITUAȚIA centralizatoare a operatorilor economici care exploatează spații de depozitare autorizate Capacitate Nr. Date de identificare Date identificare spațiu de depozitare aflat Din care : Autorizație de totală Tipul crt. depozit operator economic în exploatare instalației autorizată Magazie (serie/nr) (denumire, adresă,tel.) (denumire, adresă, tel, e-mail) Siloz (tone ) de cântărire (tone) (tone) Iaşi, strada Moara de foc nr.2, telefon : cântar Compan SA Iaşi, strada 1 22/0000243 0232/252150, fax :0232/252152, email : 1500 1500 * automat Moara de Foc nr.2 [email protected] tichet Motrif SRL, Iaşi, strada Comuna Trifeşti, judeţul Iaşi , telefon : cântar 2 22/0000244 Piaţa Voievozilor bloc 0232/251836, fax : 0232/210315, email 1000 1000 mecanic A8‐9 : [email protected] * SCA Moldova Ţigănaşi Ferma Mixtă nr.4 sat Cîrniceni, comuna cântar 3 22/0000246 comuna Ţigănaşi judeţul Ţigănaşi , telefon : 0232/299237, fax : 4350 * 4350 automat Iaşi 0232/268197, tichet Baza Mirceşti, comuna Mirceşti, judeţul cântar Prutul SA Galaţi, strada 1500 4 22/0000248 Iaşi ,telefax : 0232/767906, 6500 * automat Ana Ipătescu, nr.12 5000 [email protected] tichet Suinprod SA, Roman, Baza Stolniceni Prăjescu. Gara Muncel, cântar 5 22/0000249 strada Ştefan cel Mare judeţul Iaşi , telefax : 0232/743820, mail 11700 * 11700 mecanic km 336, judeţul Neamţ : [email protected] Siloz Sârca , Comuna Sîrca, judeţ Iaşi , cântar Prutul SA Galaţi, strada 6 22/0000250 telefax : 0232/767661, mail : 25800 16800 9000 automat Ana Ipătescu, nr.12 [email protected] tichet Cereal Bac SRL, Săveni, Baza de recepţie Vlădeni, comuna cântar 7 22/0000251 strada Independenţei, Vlădeni, judeţul Iaşi , telefax : 14500 * 14500 mecanic nr.11, bloc D4, sc.B, 0232/264684 Capacitate Nr. -

Consilieratul Agricol Iasi (1919-1949)

Consilieratul Agricol Iaşi, Fond 261 Inventar 2539 PREFAŢĂ Consilieratele Agricole au fost înfiinţate în urma publicării în Monitorul Oficial nr. 214 din 15(28) decembrie 1918 a Decretului Lege nr. 3681, referitor la „exproprierea proprietăţilor rurale pentru cauză de utilitate naţională şi în scop de a se vinde ţăranilor cultivatori de pământ”. În baza acestui act normativ, urmau să fie expropriate o serie de terenuri cultivabile, între care „cele aparţinând Domeniului Coroanei, Casei rurale şi ale tuturor persoanelor morale, publice şi private, instituţiuni, fundaţiuni” ale oraşelor şi comunităţilor urbane. De asemenea, „peste întinderile cultivabile pentru înfiinţarea de islazuri comunale în regiunile de munte” a fost expropriată din proprietatea particulară „suprafaţa solului necesar acestor islazuri”. În judeţul Iaşi, Consilieratul Agricol Iaşi şi-a desfăşurat activitatea în perioada 1919 -1932, având sarcini lărgite în legătură cu aplicarea prevederilor legilor agrare de după primul război mondial. Multe unităţi arhivistice ale acestor ani, şi nu numai, cuprind documente care merg calendaristic dincolo de perioada de activitate a Consilieratului Agricol, 1919-1937, 1919-1939, 1919 -1943. Explicaţia ar putea fi găsită în dorinţa instituţiei care a preluat arhiva, inventarul şi atribuţiile Consilieratului, desfiinţat, de a păstra evidenţa evoluţiei unor proprietăţi, pe o anumită perioadă, în dosare deja constituite. Activitatea Consilieratului Agricol Iaşi a fost continuată de Serviciul Agricol Iaşi, înfiinţat prin „Decretul Regal -

Spoliation Vs. 'The Right Not to Lie': an Economic Theory of the 2012

International Review of Social Research 2016; 6(3): 118–128 Research Article Open Access Lucian Croitoru Spoliation vs. ‘The right not to lie’: An economic theory of the 2012 political crisis leading to the referendum to impeach the President of Romania DOI 10.1515/irsr-2016-0015 Received: October 1, 2015; Accepted: December 1, 2015 Introduction Abstract: In July 2012, Romania witnessed signs hinting at Democratic countries further show concern over the a possible erosion of political freedom. The paper shows emerging signs hinting at a possible significant erosion that these signs point to a significant shortfall in economic of political freedom in Hungary and Romania, both freedom, deeply rooted in insecure property rights and EU Member States. high corruption. Such a shortage accounts for both the In Romania, the aforementioned signs originated absence of the rule of law and many people’s reliance on in actions that directly and regrettably affected the government for a job. Voters reliant on redistribution several democratic institutions in early July 2012. (mainly employees in the public sector, pensioners and Thus, attempts have been made at severely impairing welfare recipients) who actually cast their votes have the institution of the referendum as such, which is a outnumbered the other voters and have come to think of constituent of the most important institution in any themselves as the owners not only of the redistribution democracy – free elections. The Ombudsman and the rights set forth by law, but also of the values of those Chairs of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate rights. Thus, excessive redistribution lays the groundwork were supplanted on 3 July in Parliament. -

Privind Proiectele Beneficiar in Perioada Ianuarie 2012 Membre

Asociatia Microregiunea Tara Hategului -Tinutul Padurenilor GAL tel/fax 0354 411 150, email: [email protected] COMUNICAT DE PRESA privind proiectele beneficiariilor publici finantate de catre GAL In perioada ianuarie 2012 -iunie 2015, un numar de 24 de UAT/comune, membre ale Asociatiei Microregiunea Tara Hategului -Tinutul Padurenilor GAL, au obtinut fonduri europene nerambursabile (finantate 100%), in valoare de 1.644.444 euro. Asociatia Microregiunea Tara Hategului -Tinutul Padurenilor GAL a acordat finantari nerambursabile 100% in valoare de 1.644.444 euro unui numar de 45 de proiecte de investitii depuse de 24 de beneficiari publici membri GAL in cadrul a trei masuri din Planul de Dezvoltare Locala 2007-2013/2015 a GAL, respectiv: - 41 proiecte pe Masura 41.322 - “Renovarea, dezvoltarea satelor, imbunatatirea serviciilor de baza pentru economia si populatia rurala si punerea i n valoare a mosternirii rurale” - 2 proiecte pe Masura 41.125 - “îmbunatatirea si dezvoltarea infrastructurii legate de dezvoltarea si adaptarea agriculturii si silviculturii” - 2 proiecte pe Masura 41.313d - “Incurajarea activita tilor turistice” componenta d- “Dezvoltarea si/sau marketingul serviciilor turistice legate de turismul rural “. Obiectivele de investitii finantate de Asociatia Microregiunea Tara Hategului -Tinutul Padurenilor GAL , destinate beneficiarilor publici, au constat in: - construire drum vicinal - UAT/comuna Lăpugiu de Jos; - modernizare drum comunal – UAT/comuna Lunca Cernii de Jos ; - modernizare strazi – UAT/ comunele Peștișu -

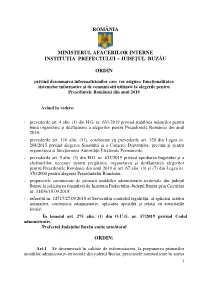

OP Desemnare Informaticieni

ROMÂNIA MINISTERUL AFACERILOR INTERNE INSTITU ŢIA PREFECTULUI – JUDE ŢUL BUZ ĂU ORDIN privind desemnarea informaticienilor care vor asigura func ționalitatea sistemelor informatice și de comunica ții utilizate la alegerile pentru Pre ședintele României din anul 2019 Având în vedere: - prevederile art. 4 alin. (1) din H.G. nr. 631/2019 privind stabilirea m ăsurilor pentru buna organizare şi desf ăş urare a alegerilor pentru Pre ședintele României din anul 2019; - prevederile art. 110 alin. (11), coroborate cu prevederile art. 120 din Legea nr. 208/2015 privind alegerea Senatului și a Camerei Deputa ților, precum și pentru organizarea și func ționarea Autorit ății Electorale Permanente; - prevederile art. 5 alin. (3) din H.G. nr. 632/2019 privind aprobarea bugetului și a cheltuielilor necesare pentru preg ătirea, organizarea și desf ășurarea alegerilor pentru Pre ședintele României din anul 2019 și art. 67 alin. (3) și (7) din Legea nr. 370/2004 pentru alegerea Pre ședintelui României; - propunerile comunicate de primarii unit ăților administrativ-teritoriale din jude țul Buz ău la solicitarea formulat ă de Institu ția Prefectului–Jude țul Buz ău prin Circulara nr. 11836/10.09.2019; - referatul nr. 12715/27.09.2019 al Serviciului controlul legalit ăţ ii, al aplic ării actelor normative, contencios administrativ, aplicarea apostilei şi rela ţii cu autorit ăţ ile locale; În temeiul art. 275 alin. (1) din O.U.G. nr. 57/2019 privind Codul administrativ, Prefectul Jude ţului Buz ău emite urm ătorul ORDIN: Art.1 Se desemneaz ă în calitate de informaticieni, la propunerea primarilor unit ăților administrativ-teritoriale din jude țul Buz ău, persoanele nominalizate în anexa 1 care face parte integrant ă din prezentul ordin, în vederea asigur ării bunei func țion ări a sistemelor informatice și de comunica ții utilizate la alegerile pentru Pre ședintele României din anul 2019. -

Romanian Economic Highlights

ROMANIAN ECONOMIC HIGHLIGHTS May 25, 2009 No. 21 SUMMARY I. ECONOMY AT WORK Stiglitz: Romanian economy fares in correlation with global financial markets Isarescu says Romania not seeing technical depression Software industry organizations: Romanian IT industry down 10 pct in 2009 II. ROMANIAN COMPANIES Italy's Pirelli plans double tire production at Slatina facility in coming four years Car maker Automobile Dacia supplements production almost 90 pct in April Xerox Romania and Moldova relies on outsourcing III. TRADE CCIB opens representation office in United Arab Emirates Eurostat: Romania's exchange deficit with Russia grows to bln. 2.719 euros IV. FINANCE-BANKS Banking system's solvency ratio topped 12 pct in Q1 Raiffeisen Bank plans investments worth 39.5 mln euros V. INDUSTRY-AGRICULTURE President Basescu: Romania is interested in European technology for new nuclear power plant Cotnari wine receives further 10 medals VI. EUROPEAN INTEGRATION No customs operation without EORI numbers as of July 1 Official in charge: Money for SAPARD payments coming in a month VII. TOURISM AND OTHER TOPICS Hotel managers compete for 800,000 sq.m. of beach Planned 93 weekly charter flights expected to bring EUR 2.3 million in revenues 1 I. ECONOMY AT WORK Trends in Romania’s economy BNR expert Lucian Croitoru: Recession predictable by economic rationale The policy focused on growing budget expenditures in real terms and the authorities’ wage policy have boosted the cyclical components of the GDP and large net capital inflows, comments Lucian Croitoru, advisor to the governor of the National Bank of Romania (BNR), in a leading article published by daily Business Standard. -

Judeţul Hunedoara Consiliul Local Vulcan

JUDEŢUL HUNEDOARA CONSILIUL LOCAL VULCAN HOTĂRÂRE NR. 118/2016 privind modificarea DOCUMENTULUI DE POZIŢIE(DP) privind modul de implementare a proiectului “Sistem de Management Integrat al Deşeurilor în Judetul Hunedoara” CONSILIUL LOCAL AL MUNICIPIULUI VULCAN, Analizând expunerea de motive, întocmită de Primarul Municipiului Vulcan, înregistrată sub nr.102 /8612/10.10.2016, prin care se propune aprobarea Planului de ocupare a funcţiilor publice pentru anul 2017; Văzând Proiectul de hotărâre nr. 110/8613/2016, raportul Compartimentului Urbanism , protecţia mediului din cadrul aparatului de specialitate al Primarului Municipiului Vulcan înregistrat sub nr. 110/8614/2016, avizul comisiei de specialitate „Economico-financiare şi de disciplină ”,, înregistrat sub nr. 145/8615/2016 precum şi avizul comisiei de specialitate „Juridică şi de Disciplină ”, înregistrat sub nr. 157/8615/2016, de pe lângă Consiliul local; Având în vedere: - adresa Asociației de Dezvoltare Intercomunitară “Sistem de Management Integrat al Deseurilor” din județul Hunedoara înregistrată la Primăria mun. Vulcan sub nr.32536/29.09.2016”, -Conformitatea cu prevederile Legii serviciilor comunitare de utilităţi publice nr. 51/2016 cu modificările şi completările ulterioare -Nota de Fundamentare privind necesitatea aprobării modificării Documentului de Poziţie (DP) privind modul de implementare a Proiectului „Sistem de Management Integrat al Deseurilor in Judetul Hunedoara; -Prevederile HCL nr.86/2013 privind aprobarea Documentului de poziţie municipiului Vulcan împreuna -

1 1. President Traian Basescu Asks for Gov't Strategy for Black Sea Gas

Embassy of Romania in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland ____________________________________________________________________________________________ No. 14/ 7th Year POLITICS 1. President Traian Basescu asks for Gov't strategy for Black Sea gas transit to be made via Transgaz 2. BEC - final results: Iohannis 54.43 pct, Ponta 45.56 pct 3. Constitutional Court validates presidential elections: Klaus Iohannis is Romania's President 4. Klaus Iohannis - President-elect (bio) 5. IRES poll: Over 80pct of Romanians expecting Iohannis to make good on his electoral promises 6. Romanian President-elect Iohannis meets Chisinau mayor Chirtoaca 7. Bogdan Aurescu is the new Foreign Affairs Minister and Hegedus Csilla, the new Culture Minister and Deputy Prime Minister 8. Foreign Minister Aurescu, U.S. chargé d'affaires Thompson discuss Strategic Partnership guidelines for 2015 9. Present government coalition benefits from support of 67% of MPs 10. Draft law on amnesty and pardons rejected by Chamber of Deputies 11. The international conference "25 years after the fall of communist dictatorships in Eastern Europe: looking back, looking forward"starts in Bucharest 12. Gorbachev's message to conference "25 Years since the Collapse of Communist Dictatorships in Eastern Europe: Looking Back, Looking Forward" 13. Mast Stepping Ceremony - dedicated to the anti-missile facility Aegis Ashore at the military base at Deveselu 14. MAE does not recognize the so-called Treaty on Allied Relations and Strategic Partnership between the Russian Federation and Abkhazia ECONOMICS 1. Romania ranks 52 of 189 countries in Paying Taxes 2015 top 2. The cut VAT on meat and meat products, conducting 3.5 billion euros in annual businesses 3.