Summative Evaluation of “First Priority: No More ‘Invisible’ Children!” Evaluation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

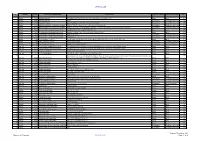

December 2020 Contract Pipeline

OFFICIAL USE No Country DTM Project title and Portfolio Contract title Type of contract Procurement method Year Number 1 2021 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways SupervisionRehabilitation Contract of Tirana-Durres for Rehabilitation line and ofconstruction the Durres of- Tirana a new Railwaylink to TIA Line and construction of a New Railway Line to Tirana International Works Open 2 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Airport Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 3 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Asset Management Plan and Track Access Charges Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 4 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Albania: Tourism-led Model For Local Economic Development Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 5 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Infrastructure and Tourism Enabling Programme: Gender and Economic Inclusion Programme Manager Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 6 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Rehabilitation of Vlore - Orikum Road (10.6 km) Works Open 2022 7 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Upgrade of Zgosth - Ura e Cerenecit road Section (47.1km) Works Open 2022 8 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Works supervision Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 9 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity PIU support Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 10 Albania 51908 Kesh Floating PV Project Design, build and operation of the floating photovoltaic plant located on Vau i Dejës HPP Lake Works Open 2021 11 Albania 51908 -

Medici Veterinari De Libera Practica Buzau

AUTORITATEA NAŢIONALĂ SANITARĂ VETERINARĂ ŞI PENTRU SIGURANŢA ALIMENTELOR DIRECŢIA SANITARĂ VETERINARĂ ŞI PENTRU SIGURANŢA ALIMENTELOR BUZĂU DATELE DE CONTACT ALE MEDICILOR VETERINARI DE LIBERĂ PRACTICĂ ABILITAȚI CU ACTIVITATEA DE IDENTIFICARE ȘI ÎNREGISTRARE A ANIMALELOR Nr. Localitatea Denumirea societății Numele medicului veterinar Telefon contact crt. 1 Amaru S.C VLAMIVET ANIMAL CARE BOANCA IONUT 0745005662 2 Balaceanu SC VET CLASS MINTOIU CIPRIAN 0722485922 3 Balta Alba SC BIOSS SETUP STANCIU C-TIN 0723644286 4 Beceni SC POLO VET HOSTINAR SILVIU 0741253594 5 Berca SC ROFARMVET TUDOSIE DOINA 0740144922 6 Bisoca SC COLIVET COMANESCU GEORGICA 0745005652 7 Blajani CMVI SAMPETRU DECEBAL SANPETRU DECEBAL 0751049907 8 Boldu SC FLOREA VET 99 SRL FLOREA VASILE 0748213746 9 Bozioru SC YANA VET POPA TATIANA 0723259597 10 Bradeanu SC MAXIVET FARMING SRL PINGHEL STEFAN ROMICA 0735553667 11 Braesti SC DIAMOND VET MERCAN STEFAN 0749072505 12 Breaza SC MARIUCA & DAVID CIOBANU OVIDIU NICUSOR 0722971808 13 Buda SC ZOOVET IBRAC LEONTINA 0726329778 14 Buzau SC SALVAVET TABACARU VASILE 0722221552 15 C. A. Rosetti RO FARMAVET SRL CRETU MARIN 0729840688 16 Canesti CMVI GHERMAN SIMONA GHERMAN SIMONA 0745108469 17 Caragele SC CORNEX 2000 SRL CARBUNARU ADRIAN 0722565985 18 Catina CMVI VOROVENCI ALIN VOROVENCI ALIN 0740254305 19 Cernatesti SC VETERINAR SERVICE BRATU GEORGE Pagina 1 din 4 Adresa: Municipiul Buzău, strada Horticolei, nr. 58 bis, Cod Poştal 120081; Telefon: 0238725001, 0758097100, Fax: 0238725003 E-mail: [email protected] , Web: http://www.ansvsa.ro/?pag=565&jud=Buzau -

JUDEȚ UAT NUMAR SECȚIE INSTITUȚIE Adresa Secției De

NUMAR JUDEȚ UAT INSTITUȚIE Adresa secției de votare SECȚIE JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 1 Directia Silvică Vrancea Directia Silvică Vrancea Strada Aurora ; Nr. 5 JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 2 Teatrul Municipal Focşani Teatrul Municipal Focşani Strada Republicii ; Nr. 71 Biblioteca Judeţeană "Duiliu Zamfirescu" Strada Mihail JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 3 Biblioteca Judeţeană Duiliu Zamfirescu"" Kogălniceanu ; Nr. 12 Biblioteca Judeţeană "Duiliu Zamfirescu" Strada Nicolae JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 4 Biblioteca Judeţeană Duiliu Zamfirescu"" Titulescu ; Nr. 12 Şcoala "Ştefan cel Mare" - intrarea principală Strada JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 5 Şcoala Ştefan cel Mare" - intrarea principală" Ştefan cel Mare ; Nr. 12 Şcoala "Ştefan cel Mare" - intrarea elevilor Strada Ştefan JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 6 Şcoala Ştefan cel Mare" - intrarea elevilor" cel Mare ; Nr. 12 Şcoala "Ştefan cel Mare" - intrarea secundara Strada JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 7 Şcoala Ştefan cel Mare" - intrarea secundara" Ştefan cel Mare ; Nr. 12 JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 8 Colegiul Tehnic Traian Vuia"" Colegiul "Tehnic Traian Vuia" Strada Coteşti ; Nr. 52 JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 9 Colegiul Tehnic Traian Vuia"" Colegiul "Tehnic Traian Vuia" Strada Coteşti ; Nr. 52 Poliţia Municipiului Focşani Strada Prof. Gheorghe JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 10 Poliţia Municipiului Focşani Longinescu ; Nr. 33 Poliţia Municipiului Focşani Strada Prof. Gheorghe JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 11 Poliţia Municipiului Focşani Longinescu ; Nr. 33 Colegiul Economic "Mihail Kogălniceanu" Bulevardul JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 12 Colegiul Economic Mihail Kogălniceanu"" Gării( Bulevardul Marx Karl) ; Nr. 25 Colegiul Economic "Mihail Kogălniceanu" Bulevardul JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 13 Colegiul Economic Mihail Kogălniceanu"" Gării( Bulevardul Marx Karl) ; Nr. 25 JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 14 Şcoala Gimnazială nr. -

Indicatori Fizici

"PROIECTUL REGIONAL DE DEZVOLTARE A INFRASTRUCTURII DE APA SI APA UZATA DIN JUDETUL BUZAU, IN PERIOADA 2014-2020" Tabel 1 Indicatorii fizici aferenti sistemului de alimentare cu apa din localitatile impactate de proiect* Cantitate / (UAT) Nr. ID Descriere U.M. UAT TOTAL Crt. POIM CJ UAT UAT UAT UAT UAT Valea UAT UAT UAT UAT UAT UAT UAT UAT UAT UAT UAT Ramnicu Buzau** Buzau Nehoiu Patarlagele Magura Ramnicului Topliceni Grebanu Cislau Cernatesti Merei Viperesti Manzalesti Lopatari Calvini Chiojdu Puiesti Sarat SISTEM DE ALIMENTARE CU APA 1 - Foraje noi buc 27 20 - - 10 - - - - - - - - 57 - - - - - 2 - Reabilitare foraje buc - - - - - - - - 1 - - - - - - 1 - - - 3 - Extindere si reabilitare captare cu dren buc - - - - - - 1 - - - - - - 1 - - - - - Reabilitare captare de suprafata / 4 - buc 1 - - - - - - - - - - - 1 - 2 Reabilitare desnisipator - - - - Conducta de aductiune/transport/legatura 5 2S72 m 1,104 4,379 18,307 212 10,979 10,915 - 1,297 - - - - 8,440 103,137 noua 47,504 - - - - 6 2S73 Conducta de aductiune - reabilitare m 692 11,842 3,876 - - - - 295 - - - - - - 16,705 - - - - Conducte de descarcare in 7 - m - 3,508 - - - - - - - - - - - 3,508 emisar/evacuare apa spalare - - - - - 8 2S78 Statie de clorinare noua buc 6 1 3 - 1 - 2 3 - 1 - - - - 1 18 - - - 9 2S78 Statie de tratare noua buc 1 1 - - - - - - - - - - - 2 - - - - - 10 2S78 Statie de tratare - reabilitare si extindere buc 1 - - - 1 - - - - - - - 1 - 3 - - - - 11 - Statie de pompare noua buc 4 - 2 6 6 - 3 7 2 - 1 2 - 5 6 1 45 - - 12 - Statie de pompare - reabilitare buc -

Ministerul Sănătăţii Informare Privind Centrele De Permanenta Care Au Functionat in Judetul Buzau

MINISTERUL SĂNĂTĂŢII DIRECTIA DE SĂNĂTATE PUBLICĂ A JUDEŢULUI BUZĂU Str. Stadionului nr.7. SE APROBA, Tel./fax: 0238-710.860 DIRECTOR EXECUTIV, E-mail: [email protected] DR.ACSINTE VENERA INFORMARE PRIVIND CENTRELE DE PERMANENTA CARE AU FUNCTIONAT IN JUDETUL BUZAU Conform prevederilor Ordinului MSF nr.151/2002 pentru aprobarea Regulamentului privind Organizarea si Functionarea Centrelor de Permanenta in Asistenta Primara si a HGR nr.1521/2002 pentru aprobarea Contractului Cadru privind Conditiile Acordarii Asistentei Medicale Primare in cadrul Sistemului de Asigurari Sociale de Sanatate in Asistenta Medicala Primara in Judetul Buzau- DIRECTIA DE SANATATE PUBLICA a dispus infiintarea, incepand cu 01.09.2003- a 8 centre de permanenta , cu urmatoarea locatie: 1.Centrul de Permanenta Buzau -Ambulatoriu de Specialitate al Spitalului Judetean Buzau -63 Medici de Familie 2. Centrul de Permanenta Rm.Sarat -Statia de Ambulanta Rm.Sarat -19 Medici de familie 3. Centrul de Permanenta Boldu -Dispensarul Medical Boldu- Comuna Boldu -Teritoriu deservit- Valcelele, Balta Alba, Boldu, Ghergheasa, Ramnicelu -6 Medici de Familie 4. Centrul de Permanenta Smeeni -Spitalul Smeeni- Comuna Smeeni -Teritoriu deservit- Smeeni, Gheraseni, Bradeanu,Tintesti 5. Centrul de Permanenta Sageata -Punctul Sanitar Gavanesti-Comuna Sageata -Teritoriu deservit- Sageata, Vadu-Pasii, Robeasca -7 Medici de familie 6. Centrul de Permanenta Cilibia -Dispensarul Medical Cilibia-Comuna Cilibia -Teritoriu deservit- Galbinasi,Cilibia,C.A.Rosetti,Rusetu,Luciu,Largu -6 Medici de Famnilie 7. Centrul de Permanenta Patarlagele -Centrul de Sanatate Patarlagele- Comuna Patarlagele MINISTERUL SĂNĂTĂŢII DIRECTIA DE SĂNĂTATE PUBLICĂ A JUDEŢULUI BUZĂU Str. Stadionului nr.7. SE APROBA, Tel./fax: 0238-710.860 DIRECTOR EXECUTIV, E-mail: [email protected] DR.ACSINTE VENERA -Teritoriu deservit- Buda-Craciunesti, Clavini, Catina, Panatau, Patarlagele,Viperesti, Colti 8. -

20.00 Furnizorii De Medicamente Aflaţi În

FURNIZORII DE MEDICAMENTE AFLAŢI ÎN RELAŢIE CONTRACTUALĂ CU CAS NEAMT NOIEMBRIE 2016 SI PROGRAMUL DE LUCRU AL ACESTORA Adresa/farmacie punct Adresa furnizor ( adresa de lucru ( adresa completă: localitate, str., completă: localitate, Telefon/fax program orar Nr. Denumire furnizor de nr., bl, sc, etaj, ap, str., nr., bl, sc, etaj, ap, farmacie/punct farmacie/punct de crt. medicamente judeţ/sector) Telefon/fax judeţ/sector) de lucru lucru FARMACIA UNIC Piatra Neamt, Piata Stefan cel Mare, nr. 1, L-V: 08.00 - 20.00 Complex Comercial Unic, S: 09.00 - 15.00 jud. Neamt 0233221971 D: 09.00 - 13.00 FARMACIA SF. ANA sat Pangaracior, comuna Pangarati, jud. Neamt 0233221971 L-V: 09.00 - 17.00 L-V: 07.30 - 21.00 S: 7.30 - 20.00 FARMACIA SF.MARIA 1, S: 07.30 – 20.00 ROMAN, str. Bogdan Dragos nr.18bis, Jud. D: 08.00 – 13.30 Neamt 0758817456 FARMACIA SF.MARIA 2, L-V: 08.00 – 20.00 ROMAN, str.Cuza Voda nr. 13 A, jud. Neamt 0758817455 S-D: 08.00 – 13.00 L-V: 08.00 – 16.00 FARMACIA SF. ANTON, S: 07.30 – 15.00 SC A & B PHARM SABAOANI, str. CORPORATION SRL BROSTENI, COM. BAHNA, jud. Orizontului nr.1, Jud. 1 c+g / pns Neamt 0233743860 Neamt 0758817457 D: 09.00 – 12.00 L-V: 08.00 – 16.00 SC ADONIS FARM SRL S: 07.00 - 15.00 2 c+g / pns TUPILATI JUDET NEAMT 0233782075 TUPILATI JUDET NEAMT 0233782075 TG. NEAMT, STR. ION PIPIRIG, STR. ION L-V: 08.00 - 15.00 SC ALCOMED FARM SRL CREANGA, NR. -

Colecţia De Planuri

ARHIVELE NAŢIONALE DIRECŢIA JUDEŢEANĂ BUZĂU A ARHIVELOR NAŢIONALE INVENTAR COLECŢIA DE PLANURI SJAN Buzau 680 u.a. 45 pag. Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei 1 COLECŢIA PLANURI Prefaţă inventar Colecţia de planuri conţine un număr de 681 documente de acest gen, documente care redau unele situaţii şi stări de lucruri geo-fizice, politice, militare, administrative, funciare, silvice, de proiectare şi construcţie pentru diferiţi ani sau momente istorice. Planurile, care numeric sunt preponderente în colecţie, privesc judeţul Buzău, şi oraşul Buzău în primul rând. Cele mai numeroase sunt planurile de moşii situate în judeţul Buzău, întocmite la sfârşitul secolului al XIX lea şi în primele decenii ale secolului al XX lea, pentru rezolvarea unor succesiuni, vânzări-cumpărări, delimitări, încălcări de proprietăţi. Dintre planurile de moşii menţionăm proprietăţile statului de la Buzău, Amara, Rm. Sărat şi ale moşiilor ce aparţin unor mari proprietari precum Lascăr Catargiu, Maria Lucasievici, A. Popovici. Alte planuri prezintă delimitarea moşiilor în loturi cedate locuitorilor în urma reformei agrare de la 1921. colecţia mai cuprinde şi schiţe, planuri de construcţie pentru diferite instituţii publice precum Liceul Comercial Rm. Sărat, Şcoala Normală de fete Buzău, Biserica Buna Vestire. De asemenea, informaţii cu caracter statistic se găsesc în planul cu situaţia demografică a fostului judeţ Rm. Sărat din anul 1941. Astfel, aceste documente furnizează, în urma studierii lor, informaţii preţioase asupra evoluţiei administrativ-teritoriale, demografice şi nu în ultimul rând economice ale judeţului Buzău. Inventarul colecţiei a fost completat de d-na Manole Liliana. Întocmit, Insp. sup. Bulfan Cătălina SJAN Buzau Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei 2 INVENTAR AL COLECŢIEI DE PLANURI Nr. -

Coleoptera: Staphylinidae) in Some Riparian Ecosystems of South-Eastern Romania

Travaux du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle © 30 Décembre Vol. LIV (2) pp. 409–423 «Grigore Antipa» 2011 DOI: 10.2478/v10191-011-0026-y CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE KNOWLEDGE ON STAPHYLINIDS (COLEOPTERA: STAPHYLINIDAE) IN SOME RIPARIAN ECOSYSTEMS OF SOUTH-EASTERN ROMANIA MELANIA STAN Abstract. The diversity of the staphylinid fauna is investigated in some riparian ecosystems along rivers of south-east Romania: the Danube, Prut, Siret, Buzău. 94 staphylinid species and subspecies were identified from 23 investigated sites. Thecturota marchii (Dodero) is a new record for the Romanian fauna. Leptobium dimidiatum (Grideli), a rare species, is recorded from a new site, the second record from Romania. Résumé. On présente la diversité de la faune de staphylinides dans quelques écosystèmes ripariens qui se trouvent le long des rivières du sud-est de la Roumanie: Danube, Prut, Siret, Buzău. 94 espèces et sous-espèces de staphylinides y ont été trouvées, en 23 sites. Theucturota marchii (Dodero) est signalée pour la première fois en Roumanie. Leptobium dimidiatum (Grideli), une espèce rare, est signalée dans un nouveau site, le deuxième sur le territoire roumain. Pour chaque espèce on présente le site où elle a été trouvée, la date, la nombre d’exemplaires (pour la plupart le sexe), legit. Sur la base des observations faites sur le terrain on offre une brève référence sur la caractéristique écologique des espèces. Key words: Staphylinidae, riparian ecosystems, faunistics. INTRODUCTION The hydrobiologic regime represents the most important control element for the existence, characteristics and maintaining of the wetland types and of their characteristic processes. Riparian areas are very important for the delimitation of the ecosystems, but especially in the specific functions which they have within the ecosystem complexes: flooding control, protection against erosion, supplying/ discharging of the underground waters, nutrient retention, biomass export, protection against storms, water transportation, stabilization of the microclimate. -

Alegeri Locale 2020 ‐ Judeţul Neamţ

ALEGERI LOCALE 2020 ‐ JUDEŢUL NEAMŢ Circumscripţia electorală nr. 1 ‐ MUNCIPIUL PIATRA NEAMŢ Localitate Functia Nume Prenume domiciliu P CIOCOIU MIHAI‐GABRIEL PIATRA‐NEAMŢ L ACHIMENCO ANDREI‐ŞTEFAN Circumscripţia electorală nr. 2 ‐ MUNICIPIUL ROMAN Localitate Functia Nume Prenume domiciliu P HULEA GABRIELA ROMAN L ALEXA AURELIAN‐CONSTANTIN ROMAN Circumscripţia electorală nr. 3 ‐ ORAŞUL BICAZ Localitate Functia Nume Prenume domiciliu P LEȚ GABRIELA ALINA PIATRA NEAMȚ L POPA NICOLETA‐ADRIANA BICAZ Circumscripţia electorală nr. 4 ‐ ORAŞUL ROZNOV Localitate Functia Nume Prenume domiciliu P IRINA ALINA‐ELENA ROZNOV L IONESCU VIORICA PIATRA‐NEAMŢ Circumscripţia electorală nr. 5 ‐ TÎRGU NEAMŢ 1 / 17 Localitate Functia Nume Prenume domiciliu P URSACHE MARIA TRANDAFIRA BRODINA (SV) L BURLACU AURORA‐VASILICA TÂRGU‐NEAMŢ Circumscripţia electorală nr. 6 ‐ AGAPIA Localitate Functia Nume Prenume domiciliu P ILIOI ELENA‐DOINA AGAPIA L BURCULEŢ ALIS‐NICOLETA PIATRA‐NEAMŢ Circumscripţia electorală nr. 7 ‐ ALEXANDRU CEL BUN Localitate Functia Nume Prenume domiciliu P FILIP CAMELIA ELENA PIATRA NEAMȚ L TANASĂ ELENA PIATRA‐NEAMŢ Circumscripţia electorală nr. 8 ‐ COMUNA BAHNA Localitate Functia Nume Prenume domiciliu P NICHIFOR MIHAELA IULIANA PIATRA‐NEAMŢ L FLEŞERIU SIMONA‐MIRELA‐ELENA PIATRA‐NEAMŢ Circumscripţia electorală nr. 9 ‐ COMUNA BĂLŢĂTEŞTI Localitate Functia Nume Prenume domiciliu P IFTIME VASILE‐ADRIAN PIATRA‐NEAMŢ L BÂRSAN COSTELA PIATRA‐NEAMŢ 2 / 17 Circumscripţia electorală nr. 10 ‐ COMUNA BÎRGĂUANI Localitate Functia Nume Prenume domiciliu P APETREI CARMEN‐MARIA PIATRA‐NEAMŢ L DAVID OLIVIA PIATRA‐NEAMŢ Circumscripţia electorală nr. 11 ‐ COMUNA BICAZ CHEI Localitate Functia Nume Prenume domiciliu P NISTOR ANCA LUCIA MOINEȘTI L MEU VIORICA‐GABRIELA BICAZ Circumscripţia electorală nr. 12 ‐ COMUNA BICAZU ARDELEAN Localitate Functia Nume Prenume domiciliu P MILOIU CIPRIAN‐DORIN PIATRA‐NEAMŢ L VASILIU ANA MARIA RALUCA Circumscripţia electorală nr. -

Buzău 651 MONITORUL OFICIALALROMÂNIEI,PARTEAI,Nr.670Bis/1.X.2010

MINISTERUL CULTURII ŞI PATRIMONIULUI NAŢIONAL LISTA MONUMENTELOR ISTORICE 2010 Judeţul Buzău MONITORUL OFICIALALROMÂNIEI,PARTEAI,Nr.670bis/1.X.2010 651 Nr. crt. Cod LMI 2004 Denumire Localitate Adresă Datare 1 BZ-I-s-B-02189 Situl arheologic din parcul Crâng municipiul BUZĂU "Parcul Crâng 2 BZ-I-m-B-02189.01 Aşezare municipiul BUZĂU "Parcul Crâng, 0,4 km SV de sec. VI - VII, Epoca castelul de apă medievală timpurie, Cultura Ipoteşti - Cândeşti 3 BZ-I-m-B-02189.02 Necropolă municipiul BUZĂU "Parcul Crâng, între sere şi mil. III - II, Epoca Obelisc bronzului mijlociu, Cultura Monteoru 4 BZ-I-m-B-02189.03 Aşezare municipiul BUZĂU "Parcul Crâng, zona sere mil. IV, Eneolitic, Obelisc,spre poarta mare a Cultura Gumelniţa Crângului 5 BZ-I-s-B-02190 SitularheologicdelaBuzău municipiul BUZĂU BuzăuE,la2kmdestaţia Buzău Sud 6 BZ-I-m-B-02190.01 Aşezare municipiul BUZĂU BuzăuE,la2kmdestaţia Buzău sec. XVII - XVIII, Sud Cultura Sântana de Mureş - Cerneahov 7 BZ-I-m-B-02190.02 Necropolă municipiul BUZĂU BuzăuE,la2kmdestaţia Buzău sec. XVII - XVIII Sud 8 BZ-I-m-B-02190.03 Aşezare municipiul BUZĂU La cca 1 km SE de Cimitirul sec. IV - V p. Chr., evreiesc, spre Pădurea Frasinu; Epoca migraţiilor târzie cca 2 km S de staţia BuzăuSud MINISTERUL CULTURII ŞI PATRIMONIULUI NAŢIONAL INSTITUTUL NAŢIONAL AL PATRIMONIULUI 652 MONITORULOFICIALALROMÂNIEI,PARTEAI,Nr.670bis/1.X.2010 Nr. crt. Cod LMI 2004 Denumire Localitate Adresă Datare 9 BZ-I-s-B-02191 Situl arheologic de la Buzău, punct "Dispensar" municipiul BUZĂU Str. Bucegi în zona Dispensarului nr. 3, până în incinta Centrului Militar şia Liceului de Arte 10 BZ-I-m-B-02191.01 Aşezare municipiul BUZĂU Str. -

APRILIE-2020-Planuri Parcelare-In Arhiva OCPI-Analogic+Digital

Lista planurilor parcelare recepţionate de OCPI Neamţ (anexă completata conform adresei ANCPI 1043513/2011) Unitatea Suprafata Nr. Administrativ corespunzatoare Analogic/ Tarla Parcela Observatii Crt Teritoriala planurilor Digital UAT parcelare HA 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 1 20,00 DA / DA UP III ua 42 72 762 10,00 DA / DA UP III ua 12 1 AGAPIA 1 1 570,00 DA / DA UP III ua 12….ua 28 – – 5,00 DA / DA O.S. Târgu-Neamţ, U.P. III Agapia, u.a. 54D, 55C, 56C 22 241 15,47 DA / DA POIANA PORCĂRIEI 36 375C 11,26 DA / DA NUCI III 2 BAHNA 31 311, 312, 310 14,21 DA / DA U.P. VI, u.a. 47A, 47B, 48 – – 34,7 DA / DA UP X, UA 1 B % – – 1237,514 DA / DA O.S. Ceahlău, U.P. I Izvoru Alb – – 169,373 DA / DA O.S. Ceahlău, U.P. II Ceahlău – – 1121,372 DA / DA O.S. Bicaz, U.P. XI Buhalniţa-Potoci – – 13,6 DA / DA UP IX UA 95% – – 15 DA / DA O.S. Brateş, U.P. IX Stejaru, u.a. 12A% – – 14 DA / DA O.S. Brateş, U.P. IX, u.a. 3B, 10A, 10B – – 0,88 DA / DA O.S. Brateş, U.P. IX Stejaru, u.a. 13B – – 1,7 DA / DA O.S. Bicaz, U.P. XI Buhalniţa-Potoci, u.a. 102M 3 BICAZ O.S. Vaduri, U.P. III Pângărăcior, u.a. 16C%, B%, F%, – 22 DA / DA – 52A%, V – – 34,7 DA / DA O.S. Bicaz, U.P. X Izvoru Muntelui, u.a. -

Comisia Judeţeanǎ Pentru Recensământul Populaţiei Şi Al Locuinţelor, Judeţul Neamț

COMISIA JUDEŢEANǍ PENTRU RECENSĂMÂNTUL POPULAŢIEI ŞI AL LOCUINŢELOR, JUDEŢUL NEAMȚ COMUNICAT DE PRESĂ 2 februarie 2012 privind rezultatele provizorii ale Recensământului Populaţiei şi Locuinţelor – 2011 Rezultatele provizorii ale Recensământului Populaţiei şi Locuinţelor (RPL 2011) din 20 Octombrie 2011 prezintă o primă estimare privind numărul populaţiei, al gospodăriilor populaţiei şi al fondului de locuinţe la nivel naţional şi teritorial. Datele provizorii ale recensământului s-au obţinut prin prelucrarea operativă a principalelor informaţii statistice însumate la nivel de localitate – municipiu, oraş, comună, pe baza tabelelor centralizatoare întocmite de recenzori după perioada de colectare a datelor, pentru cele 2487 sectoare de recensământ din judeţul NEAMȚ. Informaţiile completate în aceste tabele centralizatoare au fost agregate de comisiile judeţene având la bază procesele verbale de validare întocmite de comisiile locale de recensământ, semnate şi însuşite de membrii acestora. Rezultatele obţinute şi prelucrate până la această etapă au caracter provizoriu şi pot suferi modificări pe parcursul etapelor ulterioare de prelucrare a datelor individuale din formularele de înregistrare a persoanelor din gospodării şi locuinţe. Conform programului de desfăşurare al RPL 2011, Secretariatul Tehnic al Comisiei judeţene a RPL a centralizat la nivelul judeţului NEAMȚ informaţiile generale referitoare la numărul populaţiei stabile şi fondul de locuinţe. Rezultatele provizorii obţinute se prezintă astfel: Populaţia stabilă: 452,9 mii (452 900) persoane Gospodării: 181,7 mii (181 703) gospodării Locuinţe (inclusiv alte unităţi de locuit): 213,1 mii locuinţe (213 100 locuinţe din care: 212 806 locuinţe convenţionale şi 294 alte unităţi de locuit) Clădiri: 147,1 mii clădiri (147,1 mii clădiri din care: 146,6 mii clădiri cu locuinţe şi 531 clădiri cu spaţii colective de locuit) Detalierea pe municipii şi oraşe şi comune din judeţul NEAMȚ a indicatorilor de mai sus este prezentată în Anexă.