Extended Product Responsibility: an Economic Assessment of Alternative Policies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hazardous Waste Minimization Guide

Waste Minimization Guide Environmental Health & Safety 4202 E. Fowler Ave. OPM 100 Tampa, FL 33620 (813) 974-4036 h ttp://www.usf.edu/ehs/ June 1, 2020 Table of Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 2 Methods for Waste Minimization ............................................................................................................. 2 Source Reduction .................................................................................................................................. 2 Environmentally Sound Recycling (ESR) .................................................................................................... 4 Treatment ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Managing Waste Efficiently ...................................................................................................................... 4 Flammable Liquids and Solids ............................................................................................................... 5 Halogenated Solvents ........................................................................................................................... 5 Solvent Contaminated Towels and Rags ............................................................................................... 6 Paint related Wastes ............................................................................................................................ -

Five Principles of Waste Product Redesign Under the Upcycling Concept

International Forum on Energy, Environment Science and Materials (IFEESM 2015) Five Principles of Waste Product Redesign under the Upcycling Concept Jiang XU1 & Ping GU1 1School of Design, Jiangnan University, Wuxi, China KEYWORD: Upcycling; Redesign principle; Green design; Industrial design; Product design ABSTRACT: It explores and constructs the principles of waste product redesign which are based on the concept of upcycling. It clarifies the basic concept of upcycling, briefly describes its current development, deeply discusses its value and significance, combines with the idea of upcycling which behinds regeneration design principle from the concept of “4R” of green design, and takes real-life case as example to analyze the principles of waste product redesign. It puts forward five principles of waste product redesign: value enhancement, make the most use of waste, durable and environmental protection, cost control and populace's aesthetic. INTRODUCTION Recently, environmental problems was becoming worse and worse, while as a developing country, China is facing dual pressures that economical development and environmental protection. However, large numbers of goods become waste every day all over the world, but the traditional recycling ways, such as melting down and restructuring, not only produce much CO2, but also those restruc- tured parts or products cannot mention in the same breath with raw ones. As a result, the western countries started to center their attention to the concept of “upcycling” of green design, which can transfer the old and waste things into more valuable products to vigorously develop the green econ- omy. Nevertheless, this new concept hasn’t been well known and the old notion of traditionally inef- ficient reuse still predominant in China, so it should be beneficial for our social development to con- struct the principles of waste products’ redesign which are based on the concept of upcycling. -

Workplace Recycling

SETTING UP Workplace Recycling 1 Form a Enlist a group of employees interested in recycling and waste prevention to set up and monitor collection systems Recycling Team to ensure ongoing success. This is a great team-building exercise and can positively impact employee morale as well as the environment. 2 Determine Customize your recycling program based on your business. Consider performing a waste audit or take inventory of materials the kinds of materials in your trash & recycling. to recycle Commonly recycled business items: Single-Stream Recycling • Aluminum & tin cans; plastic & glass bottles • Office paper, newspaper, cardboard • Magazines, catalogs, file folders, shredded paper 3 Contact Find out if recycling services are already in place. If not, ask the facility or property manager to set them up. Point your facility out that in today’s environment, employees expect to recycle at work and that recycling can potentially reduce costs. If recycling is currently provided, check with the manager to make sure good recycling education materials or property are available to all employees. This will help employees to recycle right, improve the quality of recyclable materials, manager and increase recycling participation. 4 Coordinate Work station recycling containers – Provide durable work station recycling containers or re-use existing training containers like copy paper boxes. Make recycling available at each work station. with the Click: Get-Started-Recycling-w_glass or Get-Started-Recycling-without-glass to print recycling container labels. Label your trash containers as well: Get-Started-Trash-with-food waste or janitorial crew Get-Started-Trash -no-food waste. and/or staff Central area containers – Evaluate the type and size of containers for common areas like conference rooms, hallways, reception areas, and cafes, based on volume, location, and usage. -

Sector N: Scrap and Waste Recycling

Industrial Stormwater Fact Sheet Series Sector N: Scrap Recycling and Waste Recycling Facilities U.S. EPA Office of Water EPA-833-F-06-029 February 2021 What is the NPDES stormwater program for industrial activity? Activities, such as material handling and storage, equipment maintenance and cleaning, industrial processing or other operations that occur at industrial facilities are often exposed to stormwater. The runoff from these areas may discharge pollutants directly into nearby waterbodies or indirectly via storm sewer systems, thereby degrading water quality. In 1990, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) developed permitting regulations under the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) to control stormwater discharges associated with eleven categories of industrial activity. As a result, NPDES permitting authorities, which may be either EPA or a state environmental agency, issue stormwater permits to control runoff from these industrial facilities. What types of industrial facilities are required to obtain permit coverage? This fact sheet specifically discusses stormwater discharges various industries including scrap recycling and waste recycling facilities as defined by Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) Major Group Code 50 (5093). Facilities and products in this group fall under the following categories, all of which require coverage under an industrial stormwater permit: ◆ Scrap and waste recycling facilities (non-source separated, non-liquid recyclable materials) engaged in processing, reclaiming, and wholesale distribution of scrap and waste materials such as ferrous and nonferrous metals, paper, plastic, cardboard, glass, and animal hides. ◆ Waste recycling facilities (liquid recyclable materials) engaged in reclaiming and recycling liquid wastes such as used oil, antifreeze, mineral spirits, and industrial solvents. -

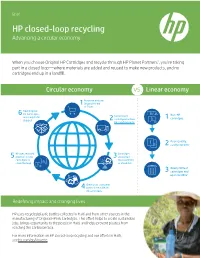

HP Closed-Loop Recycling Advancing a Circular Economy

• Brief HP closed-loop recycling Advancing a circular economy When you choose Original HP Cartridges and recycle through HP Planet Partners1, you’re taking part in a closed loop—where materials are added and reused to make new products, and no cartridges end up in a landfill. Circular economy vs. Linear economy Purchase and use 1 Original HP Ink or Toner New Original HP Cartridges 6 Return used Non-HP are ready to be 1 cartridges shipped 2 cartridges for free hp.com/hprecycle Poor-quality, 2 costly reprints2 HP uses recycled Cartridges 5 plastics3 in new 3 are sorted, cartridges to disassembled, close the loop or shredded Nearly 90% of 3 cartridges end up in landfills4 Other post-consumer 4 plastics are added to ink cartridges Redefining impact and changing lives HP uses recycled plastic bottles collected in Haiti and from other sources in the manufacturing of Original HP Ink Cartridges. This effort helps to create sustainable jobs, brings opportunity to the people in Haiti, and helps prevent plastics from reaching the Caribbean Sea. For more information on HP closed-loop recycling and our efforts in Haiti, see hp.com/go/Rosette. Together, we’re recycling for a better world The results speak for themselves. Here’s the difference HP made in 2018 by using recycled plastic in ink cartridges instead of new plastic: 60% reduction 39% less 30% average in fossil fuel water used5 carbon footprint consumption5 Enough to supply reduction5 Conserved more than 7.9 million Americans Like taking 533 cars off 7 6 for one day 8 705 barrels of oil the road for one year Bringing used products back to life With your help, we’re closing the loop. -

Annual Report 2010

Action Earth ACRES Adeline Lo Thank You Ai Xin Society for your invaluable support Anderson Junior College Andrew Tay Assembly of Youth for the Environment So many individuals, food outlets AWARE Balakrishnan Matchap and organizations gave their Betty Hoe invaluable effort, time and Bishan Community Library resources to light the path Bright Hill Temple British Petroleum (BP) towards vegetarianism. Space Bukit Merah Public Library may not have allowed us to list Cat Welfare Society Catherina Hosoi everyone, but all the same, we Central Library of the National Library Board extend our most heartfelt thanks Chong Hua Tong Tou Teck Hwee movement to you. Douglas Teo Dr Raymond Yuen Environmental Challenge Organisation Vegetarian Society (Singapore) ROS Registration No.: ROS/RCB 0123/1999 Singapore 3 Pemimpin Drive, #07-02, Lip Hing Bldg, Charity Registration No.: 1851 UEN: S99SS0065J Family Service Centre (Yishun) Singapore 576147 Foreign Domestic Worker Association (address for correspondence only) Gelin www.vegetarian-society.org Genesis Vegetarian Health Food Restaurant [email protected] Global Indian International School Green Kampung website Greendale Secondary School Green Roundtable Noah’s Ark Natural Animal Sanctuary Guangyang Primary School NUS SAVE GUI (Ground Up Initiative) NutriHub Herty Chen Post Museum Indonesia Vegetarian Society Queensway Secondary School International Vegetarian Union Prof Harvey Neo Juggi Ramakrishnan Raffles Institution Lim Yi Ting Rameshon Murugiah Kevin Tan Rosina Arquati Heng Guan Hou Serene Peh Hort Park Singapore Buddhist Federation Kampung Senang Charity and Education Singapore Kite Association Foundation Singapore Malayalee Association Loving Hut Restaurants Singapore Polytechnic Singapore Sports Council Mahaya Menon Singapore Tourism Board Maria and Ana Laura Rivarola Singapore Vegetarian Meetup Groups ANNUALREPORTFOR2010 Mayura Mohta SPCA Maitreyawira School St Anthony’s Canossian Secondary School Media Corp Straits Times MEVEG (Middle East Vegetarian Group) T. -

COMPOST FEASIBILITY STUDY April 2017

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA COMPOST FEASIBILITY STUDY April 2017 COMMISSIONED BY: District of Columbia Department of Public Works PREPARED BY: 416 LONGSHORE DRIVE ANN ARBOR, MI 48105 734.996.1361 RECYCLE.COM TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Background and Purpose .............................................................................................................................. 7 Current Operations ................................................................................................................................... 8 SSO Collection ......................................................................................................................................... 10 Processing ............................................................................................................................................... 11 Organics Collection ...................................................................................................................................... 12 Processing Technology ................................................................................................................................ 14 Organics Outreach ....................................................................................................................................... 16 SSO Curbside Collection Modeling ............................................................................................................. -

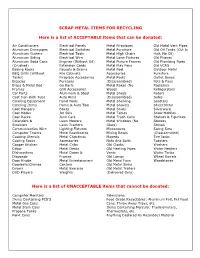

SCRAP METAL ITEMS for RECYCLING Here Is a List Of

SCRAP METAL ITEMS FOR RECYCLING Here is a list of ACCEPTABLE items that can be donated: Air Conditioners Electrical Panels Metal Fireplaces Old Metal Vent Pipes Aluminum Drainpipes Electrical Switches Metal Furniture Old Oil Tanks (Cut In Aluminum Gutters Electrical Tools Metal High Chairs Half, No Oil) Aluminum Siding Electrical Wire Metal Lawn Fixtures Old Phones Aluminum Soda Cans Engines (Without Oil) Metal Picture Frames Old Plumbing Pipes (Crushed) Extension Cords Metal Play Pens Old VCRS Baking Racks Faucets & Drains Metal Pool Outdoor Metal BBQ Grills (Without File Cabinets Accessories Furniture Tanks) Fireplace Accessories Metal Pools Outlet Boxes Bicycles Furnaces (Disassembled) Pots & Pans Brass & Metal Bed Go Karts Metal Rakes (No Radiators Frames Grill Accessories Wood) Refrigerators Car Parts Aluminum & Steel Metal Sheds Rotors Cast Iron Bath Tubs Auto Rims (Disassembled) Safes Catering Equipment Hand Tools Metal Shelving Scooters Catering Items Home & Auto Tool Metal Shovels Sheet Metal Coat Hangers Boxes Metal Studs Silverware Coat Hooks Jet Skis Metal Tables Snow Mobiles Coat Racks Junk Cars Metal Trash Cans Statues & Figurines Colanders & Lawn Mowers Metal Windows (No Stereos Strainers Lawn Tractors Glass) Stoves Communication Wire Lighting Fixtures Microwaves Swing Sets Computer Towers Metal Baseboards Mixing Bowls (Disassembled) Cooking Utensils Metal Christmas Mopeds Tire Jacks Cooling Racks Accessories Nuts And Bolts Toasters Copper Kitchen Metal Cribs Old Clocks Washers Décor Metal Desks Old Heating Pipes Water Heaters Dishwashers Metal Doors & Vents Water Tanks Disposals Frames Old Lamps Wheel Barrels Door Knobs Metal Entertainment Old Metal Fans Woodstoves Doorbells/Chimes Centers Old Metal Sinks Dryers Metal Exercise Old Metal Trailers DVD Players Weights (Delivered Only) Here is a list of UNACCEPTABLE items that cannot be donated: Computer Monitors Televisions Items Containing PCB’S Food Grade Recyclables: Aluminum Foil, Pet Food Metal Gas Cans Cans, Throw Away Trays, etc. -

III . Waste Management

III. WASTE MANAGEMENT Economic growth, urbanisation and industrialisation result in increasing volumes and varieties of both solid and hazardous wastes. Globalisation can aggravate waste problems through grow ing international waste trade, with developing countries often at the receiving end. Besides negative impacts on health as well as increased pollution of air, land and water, ineffective and inefficient waste management results in greenhouse gas and toxic emissions, and the loss of precious materials and resources. Pollution is nothing but An integrated waste management approach is a crucial part of interna- the resources we are not harvesting. tional and national sustainable development strategies. In a life-cycle per- We allow them to disperse spective, waste prevention and minimization generally have priority. The because we’ve been remaining solid and hazardous wastes need to be managed with effective and efficient measures, including improved reuse, recycling and recovery ignorant of their value. of useful materials and energy. — R. Buckminster Fuller The 3R concept (Reduce, Reuse, Recycle) encapsulates well this life-cycle Scientist (1895–1983) approach to waste. WASTE MANAGEMENT << 26 >> Hazardous waste A growing share of municipal waste contains hazardous electronic or electric products. In Europe ewaste is increasing by 3–5 per Hazardous waste, owing to its toxic, infectious, radioactive or flammable cent per year. properties, poses an actual or potential hazard to the health of humans, other living organisms, or the environment. According to UNEP, some 20 to 50 million metric tonnes of e-waste are generated worldwide every year. Other estimates expect computers, No data on hazardous waste generation are available for most African, mobile telephones and television to contribute 5.5 million tonnes to Middle Eastern and Latin American countries. -

Utilization of Waste Cooking Oil Via Recycling As Biofuel for Diesel Engines

recycling Article Utilization of Waste Cooking Oil via Recycling as Biofuel for Diesel Engines Hoi Nguyen Xa 1, Thanh Nguyen Viet 2, Khanh Nguyen Duc 2 and Vinh Nguyen Duy 3,* 1 University of Fire Fighting and Prevention, Hanoi 100000, Vietnam; [email protected] 2 School of Transportation and Engineering, Hanoi University of Science and Technology, Hanoi 100000, Vietnam; [email protected] (T.N.V.); [email protected] (K.N.D.) 3 Faculty of Vehicle and Energy Engineering, Phenikaa University, Hanoi 100000, Vietnam * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 16 March 2020; Accepted: 2 June 2020; Published: 8 June 2020 Abstract: In this study, waste cooking oil (WCO) was used to successfully manufacture catalyst cracking biodiesel in the laboratory. This study aims to evaluate and compare the influence of waste cooking oil synthetic diesel (WCOSD) with that of commercial diesel (CD) fuel on an engine’s operating characteristics. The second goal of this study is to compare the engine performance and temperature characteristics of cooling water and lubricant oil under various engine operating conditions of a test engine fueled by waste cooking oil and CD. The results indicated that the engine torque of the engine running with WCOSD dropped from 1.9 Nm to 5.4 Nm at all speeds, and its brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC) dropped at almost every speed. Thus, the thermal brake efficiency (BTE) of the engine fueled by WCOSD was higher at all engine speeds. Also, the engine torque of the WCOSD-fueled engine was lower than the engine torque of the CD-fueled engine at all engine speeds. -

Composting Toilets

Advanced Methods and Materials AMM201 Composting Toilets This Advanced Method and Material was developed jointly by the City of Bellingham SCOPE Building Department and Sustainable Connections to enhance water conservation ef- All habitable build- forts by providing a means for the installation of composting toilets. ings. DEFINITIONS Composting toilet: A BENEFITS human waste disposal system that utilizes a Composting toilets can help achieve zero waterless or low-fl ush toilet in conjunction water consumption. When used in com- with a tank in which bination with wastewater re-utilization aerobic bacteria break in irrigation and other household water down the waste. reduction techniques, costs can be cut by up to 60%. Additional benefi ts of com- PERMIT posting toilets include: REQUIREMENTS In general, the person Lower electricity costs (to pump water installing the com- and sewage) posting toilet obtains any required permits. Elimination of infrastructure costs For specifi c informa- to provide fresh water or collect and tion applicants should treat sewage contact the COB End state is a valuable fertilizer Permit Center/Build- ing Services Division Contribute up to 3 LEED® points for for more information: your project (360) 778-8300 or [email protected]. The average household spends as much as $500 per year on its water and sewer bill. A four-person household using a traditional 3.5 gallon fl ush toilet will fl ush some 70 gallons per day down the toilet (that’s an annual volume of over 25,000 gallons per year). Compared to sewage systems, on-site composting and greywater treatment has less impact on the environment (large effl uent releases into watercourses and oceans are avoided, disruption to soils systems through pipeline installation is eliminated and leakage of raw sewage into groundwater through pipe deterioration and breakage is eliminated). -

Recycling and Waste Reduction at Convenience Stores and Gas Stations

Recycling and Waste Reduction at Convenience Stores and Gas Stations Wisconsin convenience Why Recycle and Reduce Waste? stores and gas stations To save resources: Recycling saves valuable reusable resources and reduces the welcome visitors from Wisconsin energy use and pollution associated with extracting and manufacturing virgin and beyond. Often these stops materials. are the only places travelers will To reduce costs: Like other businesses, convenience stores and gas stations pay visit before arriving at their for waste disposal. In many cases, recycling services cost significantly less than trash disposal; companies that reuse or recycle more waste can save significant destinations. People used to costs on waste disposal. Reusing more materials can also reduce purchasing and recycling at home and work have handling costs. come to rely on convenience To improve customer service: Recycling demonstrates your business’ commitment stores and gas stations for to environmental protection. A recent survey indicates over 95% of Wisconsin recycling while on the road. citizens recycle regularly. People now expect to find recycling containers wherever they travel. Offering recycling is just another way to better serve your customers. Luckily, recycling not only protects valuable reusable What Should Be Recycled in Wisconsin? resources, it also helps your • Aluminum, glass, steel (tin) and bi-metal • Major appliances including air business save money and containers conditioners, clothes washers and dryers, • Plastic containers #1 and #2, including