Choice Models in Marketing: Economic Assumptions, Challenges and Trends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estimating the Benefits of New Products* by W

Estimating the Benefits of New Products* by W. Erwin Diewert University of British Columbia and NBER Robert C. Feenstra University of California, Davis, and NBER January 26, 2021 Abstract A major challenge facing statistical agencies is the problem of adjusting price and quantity indexes for changes in the availability of commodities. This problem arises in the scanner data context as products in a commodity stratum appear and disappear in retail outlets. Hicks suggested a reservation price methodology for dealing with this problem in the context of the economic approach to index number theory. Hausman used a linear approximation to the demand curve to compute the reservation price, while Feenstra used a reservation price of infinity for a CES demand curve, which will lead to higher gains. The present paper evaluates these approaches, comparing the CES gains to those obtained using a quadratic utility function using scanner data on frozen juice products. We find that the CES gains from new frozen juice products are about six times greater than those obtained using the quadratic utility function, and the confidence intervals of these estimates do not overlap. * We thank the organizers and participants at the Big Data for 21st Century Economic Statistics conference, and especially Marshall Reinsdorf and Matthew Shapiro, for their helpful comments. We also thank Ninghui Li for her excellent research assistance. Financial support was received from a Digging into Data multi-country grant, provided by the United States NSF and the Canadian SSHRC. We acknowledge the James A. Kilts Center, University of Chicago Booth School of Business, https://www.chicagobooth.edu/research/kilts/datasets/dominicks, for the use of the Dominick’s Dataset. -

CONSUMER CHOICE 1.1. Unit of Analysis and Preferences. The

CONSUMER CHOICE 1. THE CONSUMER CHOICE PROBLEM 1.1. Unit of analysis and preferences. The fundamental unit of analysis in economics is the economic agent. Typically this agent is an individual consumer or a firm. The agent might also be the manager of a public utility, the stockholders of a corporation, a government policymaker and so on. The underlying assumption in economic analysis is that all economic agents possess a preference ordering which allows them to rank alternative states of the world. The behavioral assumption in economics is that all agents make choices consistent with these underlying preferences. 1.2. Definition of a competitive agent. A buyer or seller (agent) is said to be competitive if the agent assumes or believes that the market price of a product is given and that the agent’s actions do not influence the market price or opportunities for exchange. 1.3. Commodities. Commodities are the objects of choice available to an individual in the economic sys- tem. Assume that these are the various products and services available for purchase in the market. Assume that the number of products is finite and equal to L ( =1, ..., L). A product vector is a list of the amounts of the various products: ⎡ ⎤ x1 ⎢ ⎥ ⎢x2 ⎥ x = ⎢ . ⎥ ⎣ . ⎦ xL The product bundle x can be viewed as a point in RL. 1.4. Consumption sets. The consumption set is a subset of the product space RL, denoted by XL ⊂ RL, whose elements are the consumption bundles that the individual can conceivably consume given the phys- L ical constraints imposed by the environment. -

CHOICE – a NEW STANDARD for COMPETITION LAW ANALYSIS? a Choice — a New Standard for Competition Law Analysis?

GO TO TABLE OF CONTENTS GO TO TABLE OF CONTENTS CHOICE – A NEW STANDARD FOR COMPETITION LAW ANALYSIS? a Choice — A New Standard for Competition Law Analysis? Editors Paul Nihoul Nicolas Charbit Elisa Ramundo Associate Editor Duy D. Pham © Concurrences Review, 2016 GO TO TABLE OF CONTENTS All rights reserved. No photocopying: copyright licenses do not apply. The information provided in this publication is general and may not apply in a specifc situation. Legal advice should always be sought before taking any legal action based on the information provided. The publisher accepts no responsibility for any acts or omissions contained herein. Enquiries concerning reproduction should be sent to the Institute of Competition Law, at the address below. Copyright © 2016 by Institute of Competition Law 60 Broad Street, Suite 3502, NY 10004 www.concurrences.com [email protected] Printed in the United States of America First Printing, 2016 Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication (Provided by Quality Books, Inc.) Choice—a new standard for competition law analysis? Editors, Paul Nihoul, Nicolas Charbit, Elisa Ramundo. pages cm LCCN 2016939447 ISBN 978-1-939007-51-3 ISBN 978-1-939007-54-4 ISBN 978-1-939007-55-1 1. Antitrust law. 2. Antitrust law—Europe. 3. Antitrust law—United States. 4. European Union. 5. Consumer behavior. 6. Consumers—Attitudes. 7. Consumption (Economics) I. Nihoul, Paul, editor. II. Charbit, Nicolas, editor. III. Ramundo, Elisa, editor. K3850.C485 2016 343.07’21 QBI16-600070 Cover and book design: Yves Buliard, www.yvesbuliard.fr Layout implementation: Darlene Swanson, www.van-garde.com GO TO TABLE OF CONTENTS ii CHOICE – A NEW STANDARD FOR COMPETITION LAW ANALYSIS? Editors’ Note PAUL NIHOUL NICOLAS CHARBIT ELISA RAMUNDO In this book, ten prominent authors offer eleven contributions that provide their varying perspectives on the subject of consumer choice: Paul Nihoul discusses how freedom of choice has emerged as a crucial concept in the application of EU competition law; Neil W. -

Lecture Notes General Equilibrium Theory: Ss205

LECTURE NOTES GENERAL EQUILIBRIUM THEORY: SS205 FEDERICO ECHENIQUE CALTECH 1 2 Contents 0. Disclaimer 4 1. Preliminary definitions 5 1.1. Binary relations 5 1.2. Preferences in Euclidean space 5 2. Consumer Theory 6 2.1. Digression: upper hemi continuity 7 2.2. Properties of demand 7 3. Economies 8 3.1. Exchange economies 8 3.2. Economies with production 11 4. Welfare Theorems 13 4.1. First Welfare Theorem 13 4.2. Second Welfare Theorem 14 5. Scitovsky Contours and cost-benefit analysis 20 6. Excess demand functions 22 6.1. Notation 22 6.2. Aggregate excess demand in an exchange economy 22 6.3. Aggregate excess demand 25 7. Existence of competitive equilibria 26 7.1. The Negishi approach 28 8. Uniqueness 32 9. Representative Consumer 34 9.1. Samuelsonian Aggregation 37 9.2. Eisenberg's Theorem 39 10. Determinacy 39 GENERAL EQUILIBRIUM THEORY 3 10.1. Digression: Implicit Function Theorem 40 10.2. Regular and Critical Economies 41 10.3. Digression: Measure Zero Sets and Transversality 44 10.4. Genericity of regular economies 45 11. Observable Consequences of Competitive Equilibrium 46 11.1. Digression on Afriat's Theorem 46 11.2. Sonnenschein-Mantel-Debreu Theorem: Anything goes 47 11.3. Brown and Matzkin: Testable Restrictions On Competitve Equilibrium 48 12. The Core 49 12.1. Pareto Optimality, The Core and Walrasian Equiilbria 51 12.2. Debreu-Scarf Core Convergence Theorem 51 13. Partial equilibrium 58 13.1. Aggregate demand and welfare 60 13.2. Production 61 13.3. Public goods 62 13.4. Lindahl equilibrium 63 14. -

Consumer Choice in Health Care: a Literature Review

Possibility or Utopia? Consumer Choice in Health Care: A Literature Review INEKE VAN BEUSEKOM, SILKE TÖNSHOFF, HAN DE VRIES, CONNOR SPRENG, EMMETT B. KEELER TR-105-BF March 2004 Prepared for the Bertelsmann Foundation The research described in this report was prepared for the Bertelsmann Foundation. The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research organization providing objective analysis and effective solutions that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors around the world. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. R® is a registered trademark. © Copyright 2004 RAND Corporation All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from RAND. Published 2004 by the RAND Corporation 1700 Main Street, P.O. Box 2138, Santa Monica, CA 90407-2138 1200 South Hayes Street, Arlington, VA 22202-5050 201 North Craig Street, Suite 202, Pittsburgh, PA 15213-1516 RAND URL: http://www.rand.org/ To order RAND documents or to obtain additional information, contact Distribution Services: Telephone: (310) 451-7002; Fax: (310) 451-6915; Email: [email protected] Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..........................................................................................11 2. Theoretical framework ............................................................................14 3. Methodology .........................................................................................19 -

Lecture 4 - Utility Maximization

Lecture 4 - Utility Maximization David Autor, MIT and NBER 1 1 Roadmap: Theory of consumer choice This figure shows you each of the building blocks of consumer theory that we’ll explore in the next few lectures. This entire apparatus stands entirely on the five axioms of consumer theory that we laid out in Lecture Note 3. It is an amazing edifice, when you think about it. 2 Utility maximization subject to budget constraint Ingredients • Utility function (preferences) • Budget constraint • Price vector Consumer’s problem • Maximize utility subject to budget constraint. 2 • Characteristics of solution: – Budget exhaustion (non-satiation) – For most solutions: psychic trade-off = market trade-off – Psychic trade-off is MRS – Market trade-off is the price ratio • From a visual point of view utility maximization corresponds to point A in the diagram below – The slope of the budget set is equal to − px py – The slope of each indifference curve is given by the MRS at that point • We can see that A P B, A I D, C P A. Why might we expect someone to choose A? 3 2.1 Interior and corner solutions There are two types of solution to this problem, interior solutions and corner solutions • The figure below depicts an interior solution • The next figure depicts a corner solution. In this specific example the shape of the indifference curves means that the consumer is indifferent to the consumption of good y. Utility increases only with consumption of x. Thus, the consumer purchases x exclusively. 4 • In the following figure, the consumer’s preference for y is sufficiently strong relative to x that the the psychic trade-off is always lower than the monetary trade-off. -

IB Economics HL Study Guide

S T U D Y G UID E HL www.ib.academy IB Academy Economics Study Guide Available on learn.ib.academy Author: Joule Painter Contributing Authors: William van Leeuwenkamp, Lotte Muller, Carlijn Straathof Design Typesetting Special thanks: Andjela Triˇckovi´c This work may be shared digitally and in printed form, but it may not be changed and then redistributed in any form. Copyright © 2018, IB Academy Version: EcoHL.1.2.181211 This work is published under the Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 This work may not used for commercial purposes other than by IB Academy, or parties directly licenced by IB Academy. If you acquired this guide by paying for it, or if you have received this guide as part of a paid service or product, directly or indirectly, we kindly ask that you contact us immediately. Laan van Puntenburg 2a ib.academy 3511ER, Utrecht [email protected] The Netherlands +31 (0) 30 4300 430 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 5 1. Microeconomics 7 – Demand and supply – Externalities – Government intervention – The theory of the firm – Market structures – Price discrimination 2. Macroeconomics 51 – Overall economic activity – Aggregate demand and aggregate supply – Macroeconomic objectives – Government Intervention 3. International Economics 77 – Trade – Exchange rates – The balance of payments – Terms of trade 4. Development Economics 93 – Economic development – Measuring development – Contributions and barriers to development – Evaluation of development policies 5. Definitions 105 – Microeconomics – Macroeconomics – International Economics – Development Economics 6. Abbreviations 125 7. Essay guide 129 – Time Management – Understanding the question – Essay writing style – Worked example 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 INTRODUCTION The foundations of economics Before we start this course, we must first look at the foundations of economics. -

Mathematical Economics

Mathematical Economics Dr Wioletta Nowak, room 205 C [email protected] http://prawo.uni.wroc.pl/user/12141/students-resources Syllabus Mathematical Theory of Demand Utility Maximization Problem Expenditure Minimization Problem Mathematical Theory of Production Profit Maximization Problem Cost Minimization Problem General Equilibrium Theory Neoclassical Growth Models Models of Endogenous Growth Theory Dynamic Optimization Syllabus Mathematical Theory of Demand • Budget Constraint • Consumer Preferences • Utility Function • Utility Maximization Problem • Optimal Choice • Properties of Demand Function • Indirect Utility Function and its Properties • Roy’s Identity Syllabus Mathematical Theory of Demand • Expenditure Minimization Problem • Expenditure Function and its Properties • Shephard's Lemma • Properties of Hicksian Demand Function • The Compensated Law of Demand • Relationship between Utility Maximization and Expenditure Minimization Problem Syllabus Mathematical Theory of Production • Production Functions and Their Properties • Perfectly Competitive Firms • Profit Function and Profit Maximization Problem • Properties of Input Demand and Output Supply Syllabus Mathematical Theory of Production • Cost Minimization Problem • Definition and Properties of Conditional Factor Demand and Cost Function • Profit Maximization with Cost Function • Long and Short Run Equilibrium • Total Costs, Average Costs, Marginal Costs, Long-run Costs, Short-run Costs, Cost Curves, Long-run and Short-run Cost Curves Syllabus Mathematical Theory of Production Monopoly Oligopoly • Cournot Equilibrium • Quantity Leadership – Slackelberg Model Syllabus General Equilibrium Theory • Exchange • Market Equilibrium Syllabus Neoclassical Growth Model • The Solow Growth Model • Introduction to Dynamic Optimization • The Ramsey-Cass-Koopmans Growth Model Models of Endogenous Growth Theory Convergence to the Balance Growth Path Recommended Reading • Chiang A.C., Wainwright K., Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, McGraw-Hill/Irwin, Boston, Mass., (4th edition) 2005. -

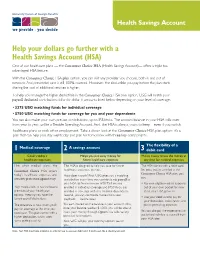

Help Your Dollars Go Further with a Health Savings Account (HSA)

Health Savings Account Help your dollars go further with a Health Savings Account (HSA) One of our healthcare plans — the Consumer Choice HSA (Health Savings Account)— offers a triple tax- advantaged HSA feature. With the Consumer Choice HSA plan option, you can visit any provider you choose, both in and out of network. And preventive care is still 100% covered. However, the deductible you pay before the plan starts sharing the cost of additional services is higher. To help you manage the higher deductible in the Consumer Choice HSA plan option, USG will match your payroll deducted contribution dollar for dollar in amounts listed below depending on your level of coverage. • $375 USG matching funds for individual coverage • $750 USG matching funds for coverage for you and your dependents You can also make your own pre-tax contributions, up to IRS limits. The account balance in your HSA rolls over from year to year, unlike a Flexible Spending Account. And, the HSA is always yours to keep – even if you switch healthcare plans or seek other employment. Take a closer look at the Consumer Choice HSA plan option: it’s a plan that can help you stay well today and plan for tomorrow with three key components. The flexibility of a Medical coverage A savings account 1 2 3 debit card Covers today’s Helps you put away money for Makes it easy to use the money at healthcare expenses future healthcare expenses any time for medical expenses Like other medical plans, the The HSA is designed to help you save for future The HSA comes with a debit card. -

“Models of Consumer Demand for Differentiated Products”

16‐741 December 2016 “Models of Consumer Demand for Differentiated Products” Timothy J. Richards and Celine Bonnet Models of Consumer Demand for Di¤erentiated Products Timothy J. Richards and Celine Bonnet September 12, 2016 Abstract Advances in available data, econometric methods, and computing power have cre- ated a revolution in demand modeling over the past two decades. Highly granular data on household choices means that we can model very speci…c decisions regarding pur- chase choices for di¤erentiated products at the retail level. In this chapter, we review the recent methods in modeling consumer demand, and their application to problems in industrial organization and strategic marketing. Keywords: consumer demand, discrete choice, discrete-continuous choice, shopping basket models, machine learning. JEL Codes: D43, L13, L81, M31. Richards is Professor and Morrison Chair of Agribusiness, Morrison School of Agribusiness, W. P. Carey School of Business, Arizona State University; Bonnet is Senior Researcher, Toulouse School of Economics and INRA, Toulouse, France. Contact author, Richards: Ph. 480-727-1488, email: [email protected]. Copyright 2016. Users may copy with permission. 1 Introduction Advances in available data, econometric methods, and computing power have created a rev- olution in demand modeling over the past two decades. Highly granular data on household choices means that we can model very speci…c decisions regarding purchase choices for dif- ferentiated products at the retail level. In this chapter, we review the recent methods in modeling consumer demand that have proven useful for problems in industrial organization and strategic marketing. Analyzing problems in the agricultural and food industries requires demand models that are able to address heterogeneity in consumer choice in di¤erentiated-product markets. -

Unit 2: Supply, Demand, and Consumer Choice

Unit 2: Supply, Demand, and Consumer Choice 1 DEMAND DEFINED What is Demand? Demand is the different quantities of goods that consumers are willing and able to buy at different prices. (Ex: Bill Gates is able to purchase a Ferrari, but if he isn’t willing he has NO demand for one) What is the Law of Demand? The law of demand states There is an INVERSE relationship between price and quantity demanded 2 Why does the Law of Demand occur? The law of demand is the result of three separate behavior patterns that overlap: 1.The Substitution effect 2.The Income effect 3.The Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility We will define and explain each… 3 Why does the Law of Demand occur? 1. The Substitution Effect • If the price goes up for a product, consumer but less of that product and more of another substitute product (and vice versa) 2. The Income Effect • If the price goes down for a product, the purchasing power increases for consumers - allowing them to purchase more. 4 Why does the Law of Demand occur? 3. Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility U-TIL-IT- Y • Utility = Satisfaction • We buy goods because we get utility from them • The law of diminishing marginal utility states that as you consume more units of any good, the additional satisfaction from each additional unit will eventually start to decrease • In other words, the more you buy of ANY GOOD the less satisfaction you get from each new unit. Discussion Questions: 1. What does this have to do with the Law of Demand? 2. -

6-2: the 2 2 × Exchange Economy

©John Riley 4 May 2007 6-2: THE 2× 2 EXCHANGE ECONOMY In this section we switch the focus from production efficiency to the allocation of goods among consumers. We begin by focusing on a simple exchange economy in which there are two consumers, Alex and Bev. Each consumer has an endowment of two commodities. Commodities are private. That is, each consumer cares only about his own consumption. Consumer h h 2 h h h, h= AB , has an endowment ω , a consumption set X = R+ and a utility function U( x ) that is strictly monotonic. Pareto Efficiency With more than one consumer, the social ranking of allocations requires weighing the utility of one individual against that of another. Suppose that the set of possible utility pairs (the “utility possibility set”) associated with all possible allocations of the two commodities is as depicted below. B U2 45 line A W U+ U = k 1 2 U 1 6.2-1: Utility Possibility Set Setting aside the question of measuring utility, one philosophical approach to social choice places each individual behind a “veil of ignorance.” Not knowing which consumer you are going 1 to be, it is natural to assign a probability of 2 to each possibility. Then if individuals are neutral Section 6.2 page 1 ©John Riley 4 May 2007 towards risk while behind the veil of ignorance, they will prefer allocations with a higher expected utility 1+ 1 2U1 2 U 2 . This is equivalent to maximizing the sum of utilities, a proposal first put forth by Jeremy Bentham.