Practicing Baptism: the Church As Communio and Congregatio Sanctorum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-Day Adventist Church from the 1840S to 1889" (2010)

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2010 The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh- day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889 Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Snorrason, Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik, "The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889" (2010). Dissertations. 144. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/144 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 by Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Adviser: Jerry Moon ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 Name of researcher: Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jerry Moon, Ph.D. Date completed: July 2010 This dissertation reconstructs chronologically the history of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Norway from the Haugian Pietist revival in the early 1800s to the establishment of the first Seventh-day Adventist Conference in Norway in 1887. -

![DICKINSON COUNTY HISTORY – CHURCHES – NORWAY, VULCAN, LORETTO [Compiled and Transcribed by William John Cummings]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9830/dickinson-county-history-churches-norway-vulcan-loretto-compiled-and-transcribed-by-william-john-cummings-359830.webp)

DICKINSON COUNTY HISTORY – CHURCHES – NORWAY, VULCAN, LORETTO [Compiled and Transcribed by William John Cummings]

DICKINSON COUNTY HISTORY – CHURCHES – NORWAY, VULCAN, LORETTO [Compiled and Transcribed by William John Cummings] Norway, Michigan, Diamond Jubilee 1891- Anderson, of Ishpeming, district 1966 Historical Album, unpaged superintendent of Sunday schools, Rev. Mr. Chindberg, of Norway, C.A. Hansen, of Norway over the past years has had Quinnesec, Rev. Otto A. Johnson, Mrs. several churches[,] namely: Baptist, Ricahrd C. Browning, Mrs. Hassell and Evangelical Covenant, Bethany Lutheran, others. All were short and snappy and Norwegian Lutheran, Swedish Methodist, were interspersed with music. Rev. T.H. English Methodist, St. Mary Episcopal, Williamson presided at both sessions. As a Norway Congregation of Jehovah result of the convention, a live county Witnesses, St. Mary’s Catholic and St. Sunday school society was formed with the Barbara’s Catholic. following officers: Churches at present are the Evangelical President – Samuel Perkins, of Norway Covenant, St. Mary’s Catholic, Jehovah M.E. church. Witnesses, English Methodist now united Vice-President – Edwin Turnquist, of with Swedish Methodist and the Vulcan Norway, and W.M. Lewis, of Iron Mountain. Methodist churches. Bethany Lutheran is Secretary – Mrss. [sic – Mrs.] Richard C. now united with the Norwegian church. St. Browning, of Iron Mountain. Mary Episcopal is no longer active, its Treasurer – Albert H. Hooper, of Iron membership having been transferred to the Mountain. Iron Mountain church. St. Barbara Catholic Elementary Superintendent – Mrs. C.A. for many years had its church in the Third Hansen, of Quinnesec. Ward but after being destroyed by fire in Secondary Superintendent – Mrs. 1925 it was rebuilt at Vulcan[,] its present George Snowden, of Iron Mountain. -

Presiding Bishop Dr. Olav Fykse TVEIT Church of Norway PO Box

Presiding Bishop Dr. Olav Fykse TVEIT Church of Norway P.O. Box 799, Sentrum Rådhusgata 1-3 0106 OSLO NO - NORWAY lutheranworld.org Per e-mail: [email protected] Geneva, in December 2020 LWF Assembly 2023 – One Body, One Spirit, one Hope Dear Presiding Bishop TVEIT, I am delighted to write with information about the next LWF Assembly, which will take place in Krakow, Poland in September 2023. As you know the Assembly is the highest governing body of the Lutheran World Federation, meeting normally every six years. It is the place and the event where the global nature of the communion is powerfully and tangibly expressed because of the participation of delegates from each of its member churches. Celebrating worship together, praying together, reflecting over God’s word and God’s calling in today’s world, the Assembly is a high point in the member churches’ common journey as a communion. As part of its business, it elects our President, appoints our Council members, and sets the strategic direction of our organization. This will be our 13th Assembly after 75 years of the LWF. I very much hope that your church will be represented and will participate fully. Plans are already underway. The LWF Executive Committee approved the theme of the Assembly, as well as the Assembly budget and the “Fair share” apportionment of Assembly fees. Your contribution is factored into this important equation that ensures we will be one body of Christ with much to offer one another from the rich diversity of our Communion. The fair share Assembly fee for The Church of Norway is calculated to be Euro 506.134. -

Church of Norway Pre

You are welcome in the Church of Norway! Contact Church of Norway General Synod Church of Norway National Council Church of Norway Council on Ecumenical and International Relations Church of Norway Sami Council Church of Norway Bishops’ Conference Address: Rådhusgata 1-3, Oslo P.O. Box 799 Sentrum, N-0106 Oslo, Norway Telephone: +47 23 08 12 00 E: [email protected] W: kirken.no/english Issued by the Church of Norway National Council, Communication dept. P.O. Box 799 Sentrum, N-0106 Oslo, Norway. (2016) The Church of Norway has been a folk church comprising the majority of the popu- lation for a thousand years. It has belonged to the Evangelical Lutheran branch of the Christian church since the sixteenth century. 73% of Norway`s population holds member- ship in the Church of Norway. Inclusive Church inclusive, open, confessing, an important part in the 1537. At that time, Norway Church of Norway wel- missional and serving folk country’s Christianiza- and Denmark were united, comes all people in the church – bringing the good tion, and political interests and the Lutheran confes- country to join the church news from Jesus Christ to were an undeniable part sion was introduced by the and attend its services. In all people. of their endeavor, along Danish king, Christian III. order to become a member with the spiritual. King Olav In a certain sense, the you need to be baptized (if 1000 years of Haraldsson, and his death Church of Norway has you have not been bap- Christianity in Norway at the Battle of Stiklestad been a “state church” tized previously) and hold The Christian faith came (north of Nidaros, now since that time, although a permanent residence to Norway in the ninth Trondheim) in 1030, played this designation fits best permit. -

Lutheran Churches in Australia by Jake Zabel 2018

Lutheran Churches in Australia By Jake Zabel 2018 These are all the Lutheran Church bodies in Australia, to the best of my knowledge. I apologise in advance if I have made any mistakes and welcome corrections. English Lutheran Churches Lutheran Church of Australia (LCA) The largest Lutheran synod in Australia, the Lutheran Church of Australia (LCA) was formed in 1966 when the two Lutheran synods of that day, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Australia (ELCA) and the United Evangelical Lutheran Church in Australia (UELCA), united into one Lutheran synod. The LCA has churches all over Australia and some in New Zealand. The head of the LCA is the synodical bishop. The LCA is also divided in districts with each district having their own district bishop. The LCA is an associate member of both the Lutheran World Federation (LWF) and the International Lutheran Council (ILC). The LCA is a member of the National Council of Churches in Australia. The LCA has official altar-pulpit fellowship with the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Papua New Guinea (ELCPNG) and Gutnius Lutheran Church of Papua New Guinea (GLCPNG) and a ‘Recognition of Relationship’ with the Lutheran Church of Canada (LCC). The LCA also has missions to the Australia Aboriginals. The LCA also has German, Finnish, Chinese, Indonesian and African congregations in Australia, which are considered members of the LCA. The LCA is also in fellowship with German, Latvian, Swedish, and Estonian congregations in Australia, which are not considered members of the LCA. Evangelical Lutheran Congregations of the Reformation (ELCR) The third largest synod in Australia, the Evangelical Lutheran Congregations of the Reformation (ELCR), formed in 1966 from a collection of ELCA congregations who refused the LCA Union of 1966 over the issue of the doctrine of Open Questions. -

Church Relations

CHURCH RELATIONS SECTION 9 Interchurch Relationships of the LCMS Interchurch relationships of the LCMS have 11. Independent Evangelical Lutheran Church been growing by leaps and bounds in the last (Germany)* triennium. In addition to our growing family of 12. Evangelical Lutheran Church of Ghana* official “Partner Church” bodies with whom the 13. Lutheran Church in Guatemala* LCMS is in altar and pulpit fellowship, the LCMS 14. Evangelical Lutheran Church of Haiti* also has a growing number of “Allied Church” bodies with whom we collaborate in various 15. Lutheran Church – Hong Kong Synod* ways but with which we do not yet have altar 16. India Evangelical Lutheran Church* and pulpit fellowship. We presently have thirty- 17. Japan Lutheran Church* nine official partnerships that have already been ** For over 13 years, The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod recognized by the LCMS in convention as well as (LCMS) has encouraged, exhorted, and convened theological good relationships with an additional forty-three discussions with the Japan Lutheran Church (JLC) to uphold the clear teaching of the infallible Word of God, as held by the Allied Church bodies, many of whom are in historic confessional Christian Church, that only men may be various stages of fellowship talks with the LCMS. ordained to the pastoral office, that is, the preaching office. In addition, the LCMS also has fourteen Sadly, tragically, and against the clear teaching of Holy “Emerging Relationships” with Lutheran church Scripture, the JLC in its April 2021 convention codified the bodies that we are getting to know but with ordination of women to the pastoral office as its official doctrine and practice. -

Table of Contents

J ÖNKÖPING I NTERNATIONAL B USINESS S CHOOL JÖNKÖPING UNIVERSITY The effects of a separation between a state church and a state Participation and religious activity in the Evangelical-Lutheran Churches in Sweden and Norway Bachelor Thesis in Political Science Author: Helena Bergström, 840720 Tutor: Associate Professor Mikael Sandberg Jönköping January 2009 Bachelor Thesis in Political Science Title: The effects of a separation between a state church and a state – Participation and religious activity in the Evangelical-Lutheran Churches in Sweden and Norway Author: Helena Bergström Tutor: Associate Professor Mikael Sandberg Date: January 2009 Key words: state church, religious activity, religious participation, separation Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to examine the effects on religious participation and activity in a country that a separation between a state and a state church has. To do this I have compared Sweden and Norway. Norway still has a state church whereas Sweden does not as of January 1 2000. I decided to examine these two countries due to their similar backgrounds, geographical location and political systems. What I found when examining Sweden was that the separation did effect the religious participation compared to Norway. But Sweden has seen a decrease in church activities for a long time; the decrease would have taken place even without the separation, since Norway also had experiences this decrease over time. So my conclusion is, if Sweden had continued to have a state church, there would have been a similar decrease. However, it would probably have been smaller, then what have taken place after the separation. The different religious activities I have looked at, baptism, confirmation and marriage, have had different development over the years and have been affected differently by the separation. -

Our Liturgy by Christian Anderson

Our Liturgy by Christian Anderson In paragraph IV of the constitution of the Norwegian Synod we read: “In order to preserve unity in liturgical forms and ceremonies, the Synod advises its congregation to use, as far as possible, the liturgy of 1685 and agenda of 1688 of the Church of Norway, or the new liturgy and agenda adopted by the Synod at Spring Grove, Minn., June, 1899, according as the several congregations may decide.” (Synod Report, 1940, p. 51) This paragraph is taken without any change from the constitution of the Old Norwegian Synod. And the advice which it gave was followed so strictly up to the time of the Merger, that there probably was no other Lutheran body in the country where there was such complete uniformity in the order of service as in the Norwegian Synod. It is true that the majority of the congregations were rather slow in adopting the so-called “New Liturgy and Agenda.” This was no doubt due in many cases to their lack of ambition to familiarize themselves with the parts that were added; but perhaps the chief reason is to be found in the fact that so many pastors served a number of congregations, and they were therefore disinclined to add anything to the work at each service. It ought to be worthwhile for us to know just what the “Liturgy of 1685 and the agenda of 1688” really is. But before calling attention to the make-up of this liturgy it may be well to be reminded of a few historical data in order to explain why this liturgy, which was prepared altogether by churchmen in Denmark, is called the liturgy and agenda of the Church of Norway. -

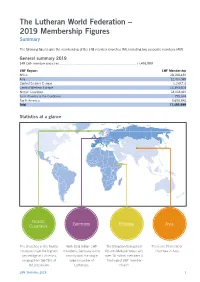

LWF 2019 Statistics

The Lutheran World Federation – 2019 Membership Figures Summary The following figures give the membership of the 148 member churches (M), including two associate members (AM). General summary 2019 148 LWF member churches ................................................................................. 77,493,989 LWF Regions LWF Membership Africa 28,106,430 Asia 12,4 07,0 69 Central Eastern Europe 1,153,711 Central Western Europe 13,393,603 Nordic Countries 18,018,410 Latin America & the Caribbean 755,924 North America 3,658,842 Total 77,493,989 Statistics at a glance Nordic Countries Germany Ethiopia Asia The churches in the Nordic With 10.8 million LWF The Ethiopian Evangelical There are 55 member countries have the highest members, Germany is the Church Mekane Yesus with churches in Asia. percentage of Lutherans, country with the single over 10 million members is ranging from 58-75% of largest number of the largest LWF member the population Lutherans. church. LWF Statistics 2019 1 2019 World Lutheran Membership Details (M) Member Church (AM) Associate Member Church (R) Recognized Church, Congregation or Recognized Council Church Individual Churches National Total Africa Angola ............................................................................................................................................. 49’500 Evangelical Lutheran Church of Angola (M) .................................................................. 49,500 Botswana ..........................................................................................................................................26’023 -

WELS Flag Presentation

WELS Flag Presentation Introduction to Flag Presentation The face of missions is changing, and the LWMS would like to reflect some of those changes in our presentation of flags. As women who have watched our sons and daughters grow, we know how important it is to recognize their transition into adulthood. A similar development has taken place in many of our Home and World mission fields. They have grown in faith, spiritual maturity, and size of membership to the point where a number of them are no longer dependent mission churches, but semi- dependent or independent church bodies. They stand by our side in faith and have assumed the responsibility of proclaiming the message of salvation in their respective areas of the world. Category #1—We begin with flags that point us to the foundations of support for our mission work at home and abroad. U.S.A. The flag of the United States is a reminder for Americans that they are citizens of a country that allows the freedom to worship as God’s Word directs. May it also remind us that there are still many in our own nation who do not yet know the Lord, so that we also strive to spread the Good News to the people around us. Christian Flag The Christian flag symbolizes the heart of our faith. The cross reminds us that Jesus shed his blood for us as the ultimate sacrifice. The blue background symbolizes the eternity of joy that awaits us in heaven. The white field stands for the white robe of righteousness given to us by the grace of God. -

Norway 2020 International Religious Freedom Report

NORWAY 2020 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution prohibits religious discrimination and protects the right to choose, practice, or change one’s faith or life stance (belief in a nonreligious philosophy). It declares the Church of Norway is the country’s established church. The government continued to provide the Church of Norway with exclusive benefits, including funds for salaries and benefits of clergy and staff. The government enacted a new law governing religious life in April that outlines how faith and life stance organizations with at least 50 registered members may apply for state subsidies, which are to be prorated as a percentage of the subsidy received by the Church of Norway based on group membership. A hate crime law punishes some expressions of disrespect for religious beliefs. On June 11, the Oslo District Court sentenced Philip Manshaus to 21 years’ imprisonment for the attack on an Islamic cultural center and the killing of his stepsister in 2019. In March, the Director of Public Prosecutions declined to bring a case to the Supreme Court after a court of appeals acquitted three men of hate speech charges arising from a 2018 incident when they raised a Nazi flag outside the site of a World War II Gestapo headquarters. The government continued to implement an action plan to combat anti-Semitism, particularly hate speech, and released a similar plan to combat anti- Muslim sentiment. The government continued to provide financial support for interreligious dialogue. A total of 807 hate-motivated crimes were reported during the year, of which 16.7 percent were religiously motivated. -

General Information About Norway

General information about Norway Geography • Located at the western and northern part of the Scandinavian peninsula. • Norway has a long land border to the east with Sweden a shorter border with Finland and an even shorter with Russia. • The cost line is one of the longest and most rugged in the world with some 50,000 islands. • 32 % of the mainline is located above the tree line and is one of Europe’s mountainous countries. • Norway’s total area is 385,179 km2 of which 94,95% is water. • The highest point is Galdhopiggen 2,569 m. • There are over 150,000 lakes. • The longest river is Glomma 604 km and the largest lake is Mjosa 352 km2. • The Gulf Stream makes Norway having a milder climate than other countries at the same latitude. • Due to the varied topography and climate, Norway has a larger number of different habitats than almost any other European Country. • During the last ice age, Norway was virtually entirely covered with a thick ice sheet. As the ice moved, valleys were carved out and the famous Fjords were created when the ice melted and filled these valleys. Population • A population of 5,312,300 (August 2018) • The population density in 2017 was 14.5 people per sq.km. • Oslo, the capital inhabits 1,000,467 (2017) followed by Bergen 255,464, Stavanger and Trondheim. • The urban population was 81.9% in 2017, growing at an average annual rate of 0.56% • The five largest urban settlements inhabit 33% of the population. • Sámi people inhabit Sápmi which covers parts of Norway but also Sweden, Finland, and Russia.