Origin and Dispersal of Common Millet and Foxtail Millet*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proso and Foxtail Millet Production

Proso and foxtail millet production R.L. Croissant and J.F. Shanahan1 no. 0.118 self-pollinated, but some outcrossing may occur when two Quick Facts varieties are planted side by side. Foxtail millet (Setaria italica) is an annual warm Proso and foxtail millet grain may be used as season grass with slender leafy stems up to 40 inches tall. livestock feed or in birdseed mixture. The inflorescence is a dense, cylindrical, bristly panicle. Foxtail millet produces a high-quality forage when The lemma and palea covering the threshed seed may be harvested at the bloom stage. white, yellow, orange or other shades including green and Millet is a very efficient utilizer of soil water and purple. Like proso, foxtail millet is highly self-pollinated, can produce grain or forage in drought but may show some outcrosses when different varieties are conditions. planted side by side. Proso millet and foxtail millet generally require swathing when harvested for grain. Acreage planted to millet annually depends on soil Climatic Requirements moisture at planting time, the price and demand for millet grain and millet hay, and Proso millet is a short season crop requiring 50 to 90 government acreage control for other crops. days from sowing to maturity for early to midseason varieties while foxtail millet requires 55 to 70 days to reach a suitable stage for hay, and 75 to 90 days for seed production. The millets, grown world-wide, are important as feed Both types of millet require relatively warm weather and food sources. During 1965 to 1985, millet production for germination and plant growth. -

Genetic Glass Ceilings Gressel, Jonathan

Genetic Glass Ceilings Gressel, Jonathan Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Gressel, Jonathan. Genetic Glass Ceilings: Transgenics for Crop Biodiversity. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.60335. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/60335 [ Access provided at 2 Oct 2021 23:39 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Genetic Glass Ceilings Transgenics for Crop Biodiversity This page intentionally left blank Genetic Glass Ceilings Transgenics for Crop Biodiversity Jonathan Gressel Foreword by Klaus Ammann The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore © 2008 The Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 2008 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 987654321 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gressel, Jonathan. Genetic glass ceilings : transgenics for crop biodiversity / Jonathan Gressel. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 13: 978-0-8018-8719-2 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 10: 0-8018-8719-4 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Crops—Genetic engineering. 2. Transgenic plants. 3. Plant diversity. 4. Crop improvement. I. Title. II. Title: Transgenics for crop biodiversity. SB123.57.G74 2008 631.5Ј233—dc22 20007020365 A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at 410-516-6936 or [email protected]. Dedicated to the memory of Professor Leroy (Whitey) Holm, the person who stimulated me to think differently. -

Millet Forage Management

Millets IOWA STATE UNIVERSITY University Extension Forage Management By Brian Lang, Extension Crop Specialist Fact Sheet BL-55, June 2001 Introduction Forage Selection for Livestock Millets are major grain crops world wide, but in Iowa All millet forages are good feed for beef and sheep. The their use is mainly as annual summer forage production choice of millet is largely dependent on seasonal needs as hay, silage, green-chop, and pasture. The and intended harvest management @ silage, pasture, sudan/sorghum forages are often the first choice for green-chop, hay, etc. summer annual forage production, but millets have been Dairy -- There is some evidence1 that Pearl Millet may gaining in popularity. cause butterfat depression in milk. Therefore, Millets grown in Iowa include: recommendations for use of Pearl Millet with lactating · Pearl Millet -- also called Cattail Millet. dairy are either to: · limit feed the millet and monitor butterfat levels · Japanese Millet -- also called Barnyard Millet. Seed · or simply avoid its use for lactating dairy shatter may lead to Barnyardgrass weed problems. · Foxtail Millet -- German and Siberian varieties seem Horses -- Do not feed Foxtail Millet as a major 2 to be the most popular for forage use. component of their diet. Foxtail Millet acts as a laxative and contains a glucoside called setarian that may damage · Proso Millet -- also called hog, hershey, and the kidneys, liver, and bones3. broomcorn millet. Table 1. Establishment and Harvest Information for Millet Forages. Typical dry matter Days from planting Harvest at boot Height when to graze, Forage Seeding yield & cutting to 36-inch height stage or 36-inch Height to graze to, millet rate schedule or boot stage height down to… Grazing interval lbs./ac. -

MILLET in Your Meals

MILLET in your Meals Issued in public interest by - An ISO 22000 Company Publication supported by NABARD (National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development) Let’s welcome Millets back into our meals Millets - Millet is the name given to a group of cereals other than wheat, rice, maize & barley. They are mostly tiny in size, round in shape & ready for usage as it is. It is acknowledged that during the Stone Age, the Millet plant was grown by the lake inhabitants of Switzerland. History reveals that since the Neolithic Era, millet, a prehistoric seed was cultivated in the dry climates of Africa and northern China. Interestingly it was millets and not rice that was a staple food in Indian, Chinese Neolithic and Korean civilizations. Eventually, millets spread all over the world. It was heavy, it was tall, It sprouted, it eared, It nodded, it hung, Indeed the lucky grains were sent down to us The black millet, the double kernelled, millet, pink sprouted and white. So goes the folk song from China- a melodious litany to the treasure trove of nutrition, the oldest food know to mankind! There are about 6,000 varieties of millet throughout the world with grains varying in colour from pale yellow, to gray, white, and red. Archaeologists say that foxtail millet is so old that no wild plant of the species is known to exist today. The Millet Story - The origin of millet is diverse with varieties coming from both Africa and Asia. Pearl millet for example comes from tropical West Africa and finger millet from Uganda or neighboring areas. -

Sudan Grass, Millets, and So'rghums At

FJJCATF Sudan Grass, Millets, and So'rghums at H. A. Schofh H. H. Rampton Agricultural Experiment Station, Oregon State College, Corvallis. Cooperating: Division of Forage Crops and Diseases, Station Bulletin 425 Bureau of Plant Industry, Soils and Agri- March 1945 cultural Engineering, United States De- Revised January 1949 partment of Agriculture. Toble of Con±en±s Page Introduction 3 Adaptations in Oregon 4 Seedbed Preparation 7 Rodents and Birds 7 Diseases Insects Sudan Grass 11 Proso 17 Foxtail Millet 20 Japanese Barnyard Millet 22 Sorghum 24 ACKNOWLEDGMENT: Forage crop work at thc Oregon Agricultural Experiment Station conducted in cooperation with the Division of Forage Crops and Diseases. Buieau of Plant Industry, Soils and Agricultural Engineering, United States Department ot Agricul- ture; creditis hcreby acknowledged as jointly due to the above named clivson am! bureau and the Oregon Agricultural Experiment Station. Figure 1. A good crop of sorghum in western Oregon. Sudan Grass, MiIIeIs, and Sorghums By H. A. SCHOTH, Senior Agronomist, and H. H. RAMPTON, Associate Agronomist Introd uction grass, millets, and sorghurns ha\Te been grown in varying SUDANacreages in several sections of Oregon for many years. These crops are of relatively minor importance but the acreage is gradually increasing as adapted and improved varieties are obtained, more satis- factory cultural practices are determined, and wider utility is devel- oped. In some sections they are now considered to be standard field crops. In others, some of them are grown as temporary or emergency crops during seasons that are unfavorable for other crops. Use of Sudan grass is increasing more rapidly than use of millets and other sorghums.it has been estimated that in 1948, the acreage had increased to approximately 45,500. -

Foxtail Millet (Setaria Italica), Grain | Feedipedia

Foxtail millet (Setaria italica), grain | Feedipedia Animal feed resources Feedipedia information system Home About Feedipedia Team Partners Get involved Contact us Foxtail millet (Setaria italica), grain Automatic translation Description Nutritional aspects Nutritional tables References Sélectionner une langue ▼ Click on the "Nutritional aspects" tab for recommendations for ruminants, pigs, poultry, rabbits, horses, fish and crustaceans Feed categories All feeds Forage plants Cereal and grass forages Legume forages Forage trees Aquatic plants Common names Other forage plants Plant products/by-products Foxtail millet, dwarf setaria, foxtail bristle grass, German millet, giant setaria, green bristle grass, green foxtail, green foxtail Cereal grains and by-products millet, Hungarian millet, Italian millet, wild foxtail millet, nunbank setaria [English]; mijo, mijo de Italia, mijo menor, moha, moha Legume seeds and by-products de Alemania, moha de Hungria, panizo común, almorejo [Spanish]; painço, milho painço, milho painço de Itália [Portuguese]; Oil plants and by-products millet d'Italie, millet des oiseaux, petit mil, sétaire verte, sétaire d'Italie [French]; Kolbenhirse, Italienische Borstenhirse ذيل الثعلب اإيطالي ;[Fruits and by-products [German]; jawawut, sekoi [Indonesian]; setária-verde [Italian]; juwawut, otèk [Javanese]; setariya [Kinyarwanda Roots, tubers and by-products [Arabic]; 粟 [Chinese]; 조 [Korean]; [Hindi]; アワ [Japanese]; [Kannada]; [Malayalam]; Sugar processing by-products [Nepali]; Щети́ нник италья́нский [Russian]; [Tamil]; [Telugu]; ขาวฟ้ ่ างหางหมา [Thai] Plant oils and fats Other plant by-products Species Feeds of animal origin Animal by-products Setaria italica (L.) P. Beauv. [Poaceae] Dairy products/by-products Animal fats and oils Synonyms Insects Other feeds Chaetochloa italica (L.) Scribn., Chaetochloa viridis (L.) Scribn., Chamaeraphis viridis (L.) Millsp., Panicum italicum L., Minerals Panicum pachystachys Franch. -

Millet Introduction “Millet” Is a Name That Has Been Applied to Several Different Annual Summer Grasses Used for Hay, Pasture, Silage, and Grain

University of Kentucky CCD Home CCD Crop Profiles College of Agriculture, Food and Environment COOPERATIVE EXTENSION SERVICE UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND ENVIRONMENT Millet Introduction “Millet” is a name that has been applied to several different annual summer grasses used for hay, pasture, silage, and grain. The millets most commonly cultivated in Kentucky, pearl millet and foxtail millet, are grown primarily as a forage for temporary pasture. If properly managed, these millets can provide high yields of good quality forage in a short period, without the risk of prussic acid poisoning. FOXTAIL MILLET (LEFT) AND PEARL MILLET (RIGHT) Pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) is higher Production Considerations yielding than foxtail millet and regrows after Establishment and management harvest if sufficient stubble is left. Dwarf Foxtail and pearl millets are planted from the varieties, which are leafier and more suited for first of May until the end of July in Kentucky. grazing, are also available. Foxtail millet (Setaria Later plantings reduce harvests and total yields. italica) is a lower-yielding grass that will not Seeding at two or more planting dates helps in regrow to produce another harvest. Because it is managing harvests. The seed can be broadcast shorter and finer-stemmed, it is easier to harvest and cultipacked, or seeded with a grain drill into as hay. It can serve as a good smother crop to be a well-prepared, firm seedbed. Seed can also be used before no-till seeding of other crops, such planted without tillage by using a no-till drill. as fescue or alfalfa. -

Forage Extension Program

Forage Extension Program Growing Millet in Montana By Dennis Cash, MSU Extension Service ([email protected]); Duane Johnson, MAES Northwestern Agricultural Research Center ([email protected]); David Wichman, MAES Central Agriculture Research Center ([email protected]) Acreage of several millet species has increased in recent years. Millet is a "Several short-term warm-season annual crop that has excellent drought hardiness. millets can Millet grain is used for human food products, livestock feed or birdseed. produce good Several millets can produce good forage yields, and are useful for forage emergency forage or a catch crop after hailed-out wheat. As warm-season yields, and are species, millets are sensitive to late spring frosts, so they should be seeded useful for after soil temperatures are consistently above 65 degrees. For emergency emergency forage during a drought, millets can out-yield sudangrass or sorghums. forage or a However with good moisture or under irrigation, other warm-season catch forages (sudangrass, sorghum, sorghum X sudangrass hybrids or corn) are crop after superior. hailed-out wheat." The primary types of millet are: Proso millet (Panicum miliaceum) is used primarily for birdseed or livestock feed. Proso millet grows to about a 30-inch height, and the stems are hollow and coarse. The leaves and stems are pubescent, and the seed heads (panicles) are large and lax. When the seed is threshed, most of the inner hulls remain attached to the grain. Seed color varies among varieties, from white, cream, red to brown or black. For birdseed production, white grain is preferred, so be sure to contact a marketer before planting. -

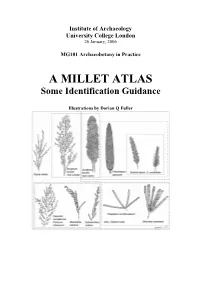

A MILLET ATLAS Some Identification Guidance

Institute of Archaeology University College London 26 January, 2006 MG101 Archaeobotany in Practice A MILLET ATLAS Some Identification Guidance Illustrations by Dorian Q Fuller Some Millet fact tables by DQ Fuller Table 1. Old World Cultivated ‘Millets’ Species Common Name Region of Origin and References Cultivation Brachiaria ramosa (L.) Stapf. (syn. Browntop millet, pedda- South India Fuller et al. 2004; Hulse et Urochloa ramosa (L.) R. D. Webster) sama al. 1980; De Wet 1995a; Kimata et al. 2000 Brachiaria deflexa (Schumach) C. E. Guinea millet, Animal Fouta Djalon Highlands, Porteres 1976; Zeven & Hubbard var. sativa Porteres Fonio Guinea, W. Africa De Wet 1982: 127; Borlaug et al. 1996: 237 Digitaria cruciata (Ness) A. Camus var. Raishan Khasi Hills, Assam; Hill tribes Bor 1955; Singh & Arora esculenta Bor of Vietnam 1972 Digitaria exilis (Kippist) Stapf. Fonio, Acha, Fundi West Africa Porteres 1976; Zeven & De Wet 1982: 128; Borlaug et al. 1996: 59ff Digitaria iburua Stapf. Black Fonio, Iburu, West Africa Porteres 1976; Zeven & Hungry Rice De Wet 1982: 128; Borlaug et al. 1996: 59ff Digitaria sangiuinalis (L.) Scop. Harry crabgrass Eurasian origin; cultivated in Porteres 1955; De Wet Kashmir, formerly in Europe 1995 Echinochloa colona ssp. frumentacea Sawa Millet Peninsular India(?), also De Wet et al. 1983c; Hilu (Link) De Wet, Prasada Rao, Mengesha cultivated in Himalayas 1994 and Brink (=E. frumentacea Link) Echinochloa crus-galli var. utilis Yabuno Barnyard Millet Japan Yabuno 1987; Hilu 1994 Eleusine coaracana (L.) Gaertn. Finger Millet, ragi East African highlands Hilu and De Wet 1976; Hilu and Johnson 1992 Eragrostis tef (Zucc.) Trotter Teff Ethiopian highlands Zeven & De Wet 1982: 130 Panicum miliaceum L. -

Developmental Stages and Floral Ontogenesis of Foxtail Millet Setaria Italica (L) P Beauv Mo Blaise, P Girardin, B Millet

Developmental stages and floral ontogenesis of foxtail millet Setaria italica (L) P Beauv Mo Blaise, P Girardin, B Millet To cite this version: Mo Blaise, P Girardin, B Millet. Developmental stages and floral ontogenesis of foxtail millet Setaria italica (L) P Beauv. Agronomie, EDP Sciences, 1992, 12 (2), pp.141-156. hal-00885461 HAL Id: hal-00885461 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00885461 Submitted on 1 Jan 1992 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Agronomy Developmental stages and floral ontogenesis of foxtail millet Setaria italica (L) P Beauv MO Blaise P Girardin1 B Millet2 1 INRA, Laboratoire d’Agronomie, BP 507, F 68021 Colmar: 2 Faculté des Sciences, Laboratoire de Botanique, Place Leclerc, F 25030 Besançon Cedex, France (Received 1 July 1991; accepted 9 December 1991) Summary — A study of the morphological development of the shoot apex the floral ontogenesis of 2 varieties of foxtail millet was made by dissection of the shoot apex of the main stem at different stages of development. Photomicrographs of the principal stages show that the beginning of inflorescence diffe- rentiation (stage B) occurs at a thermal time of 705 degree-days (basis 6 °C) when the plants have 60% visible leaves. -

The Nokth American Species of Chaetochloa

THE NOKTH AMERICAN SPECIES OF CHAETOCHLOA. By A. S. HITCHCOCK, INTRODUCTION. Tho genus ChaetocMoa is closely allied to Panicum y from which it is separated technically by the presence of bristle-like sterile branch- lets below the spikelets. Two species, introduced from Europe, are common weeds in the eastern states. One, C. lutescens (Setaria glauca of authors) , with a dense cylindric spikelike panicle or head, and yellow bristles, is called yellow foxtail or pigeon grass- The other, green foxtail (Cm viridis), has green heads. The bristly head or narrow panicle is characteristic of most of the species of the genus. One species, G. italica (Setaria italica), is cultivated under the name of millet or foxtail millet. Of this there are many varieties, such as Hungarian grass, German millet, and Golden Wonder, To these the general term millet is applied, a name which should not be confused with the common millet of Europe (Panicum miliaceum), cultivated occasionally in the United States for forage under the name of broom- corn millet, proso millet, and hog millet, The North American species of ChaetocMoa were revised in 1900 by Scribner and Merrill.1 The allies of Panicum palmifolium are here included under Chaeto- cMoa as a subgenus (Ptychophyllum). They are tropical species with broad plaited blades. Some are cultivated in greenhouses under the name of palm grass, because of the leaves which resemble those of a young palm. In a small group of species of Panicum (forming the subgenus Paurochaetium2) the ultimate branchlets are produced beyond the few to several spikelets as minute bristles. -

Native Warm-Season Grasses Identification, Establishment and Management for Wildlife and Forage Production in the Mid-South

$35 Extension PB1752 Native Warm-Season Grasses Identification, Establishment and Management for Wildlife and Forage Production in the Mid-South a manual for natural resource professionals and other land managers Native Warm-Season Grasses Identification, Establishment and Management for Wildlife and Forage Production in the Mid-South a manual for natural resource professionals and other land managers Craig A. Harper, Associate Professor/Extension Wildlife Specialist The University of Tennessee, Department of Forestry, Wildlife and Fisheries Gary E. Bates, Professor/Extension Forage Specialist The University of Tennessee, Department of Plant Sciences Michael P. Hansbrough, Private Lands Biologist USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service Mark J. Gudlin, Private Lands Liaison Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency John P. Gruchy, Research Associate The University of Tennessee, Department of Forestry, Wildlife and Fisheries Patrick D. Keyser, Associate Professor/Center for Native Grasslands Management The University of Tennessee, Department of Forestry, Wildlife and Fisheries © 2007 Craig Harper University of Tennessee Extension Institute of Agriculture Knoxville, Tennessee ISBN 978-0-9795165-0-4 Produced by the Office of Marketing and Communications Services, University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture Designed by Donna Hundley Edited by Wanda Russell Printed by the University of Tennessee Graphic Arts Service Corresponding Author: Craig A. Harper Dept of Forestry, Wildlife & Fisheries University of Tennessee Knoxville, TN 37996 [email protected]