LEC Judicial Newsletter Volume 12 Issue 3 October 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stitlyjohibited Fire Destroys

For Household Keroovola Phan* 821 COAL! coal: - Burt’s Padded Vans Hall & Walker 735 P NDORA ST. 1232 Government Street Prompt Attention, Experienced Men Residence Phone R710. TELEPHONE 83, V’UL. 51. VICTORIA, B. c., THURSDAY, JUNE 15, 1911. NO. 139. T TO-DAY’S BASEBALL NORTHWESTERN LEAGUE At Seattle—First inning; Tacoma. QUITE IT HOME "NETEMERE” DECREE 1; Seattle. 4. Second inning: Tacoma, 0; Se attle, 1. Batteries—Hall and Burns; Zackert RESOLUTION PASSED and Shea. NOVA SCOTIA STILL SPENDING ENJOYABLE At Portland—First inning.: Spokane, BY PRESBYTERIANS 1; Portland, 0. TRUE TO LIBERALISM TIME IN METROPOLIS Batteries — Schwenk and Ostdlekr j______ Bloomfield and Bradley. --------AMtlttCAN LEAGUE " Col. McLean and Officers of Vote of ChurcfT’Memb'ers'oh" At Washington— R. H. E. Government Holds 27 Out of Question of Union to Be St. Louis .................................7 1,5 1 38 Seats, Some by In Contingent Entertain Dis Washington ............ ...................g il l tinguished Party Taken on March 15 Batteries — Powell and Hatnllton, creased Majorities Clarke ; Hughes, Groom and Street. At New York-.—' R. E. Halifax. N. S.. June 15.—After London. June 15 —To-day is another Ottawa, June IB.—The Presbyterian General A»sembl> continued the dis Detroit ............'...............................o twenty-nine . year# of capable and day of glorious sunshine tempered by cussion on Church Union to-day, it New York ................... .. *............ 5 dean government at the hands of the a fresh breeze, and those who have being decided that the vote of mem Batteries—Mullln and Casey, liberal party Nava Scotia yesterday not -been tempted away by the Gold bers and adherents be taken on March age; Fisher and Sweeney. -

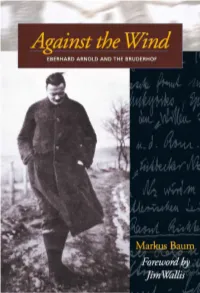

Against the Wind E B E R H a R D a R N O L D a N D T H E B R U D E R H O F

Against the Wind E B E R H A R D A R N O L D A N D T H E B R U D E R H O F Markus Baum Foreword by Jim Wallis Original Title: Stein des Anstosses: Eberhard Arnold 1883–1935 / Markus Baum ©1996 Markus Baum Translated by Eileen Robertshaw Published by Plough Publishing House Walden, New York Robertsbridge, England Elsmore, Australia www.plough.com Copyright © 2015, 1998 by Plough Publishing House All rights reserved Print ISBN: 978-0-87486-953-8 Epub ISBN: 978-0-87486-757-2 Mobi ISBN: 978-0-87486-758-9 Pdf ISBN: 978-0-87486-759-6 The photographs on pages 95, 96, and 98 have been reprinted by permission of Archiv der deutschen Jugendbewegung, Burg Ludwigstein. The photographs on pages 80 and 217 have been reprinted by permission of Archive Photos, New York. Contents Contents—iv Foreword—ix Preface—xi CHAPTER ONE 1 Origins—1 Parental Influence—2 Teenage Antics—4 A Disappointing Confirmation—5 Diversions—6 Decisive Weeks—6 Dedication—7 Initial Consequences—8 A Widening Rift—9 Missionary Zeal—10 The Salvation Army—10 Introduction to the Anabaptists—12 Time Out—13 CHAPTER TWO 14 Without Conviction—14 The Student Christian Movement—14 Halle—16 The Silesian Seminary—18 Growing Responsibility in the SCM—18 Bernhard Kühn and the EvangelicalAlliance Magazine—20 At First Sight—21 Against the Wind Harmony from the Outset—23 Courtship and Engagement—24 CHAPTER THREE 25 Love Letters—25 The Issue of Baptism—26 Breaking with the State Church—29 Exasperated Parents—30 Separation—31 Fundamental Disagreements among SCM Leaders—32 The Pentecostal Movement Begins—33 -

Recipient: Senate Committee

Recipient: Senate Committee Letter: Greetings, I would like to express my deep concern over the proposed introduction of so-called 'Ag Gag' laws - Criminal Code Amendment (Animal Protection) Bill 2015. These laws are nothing more than an attempt to protect those who abuse animals (both illegally, and within industry standard guidelines) and prevent consumers from making informed choices regarding what practices they choose to support. We do not need laws that punish and criminalise animal cruelty investigators. I believe the current laws are more than sufficient to protect private citizens from alleged trespassers and that the introduction of ‘Ag Gag’ laws would only serve to protect industries that for too long have freely gotten away with animal abuse. The public has every right to be aware of what they choose to participate in, and it is only through the efforts of animal activists that they are able to do so. I implore you to protect the right of the public to know the truth by opposing the introduction of Ag Gag laws. Comments Name Location Date Comment Renate McLaughlin Melbourne, GU 2015-03-09 I totally believe in supporting animals connie tonna Georgetown, SC 2015-03-09 This is Shameful - even with laws protecting the animals they still undergo severe abuse - if this law is passed the animals will have no protection whatsoever. Janet Veevers Australia 2015-03-09 Animals have, to our great shame, very little protection in law on Australia. We need more protection for animals and more stringent punishments for their abusers. We are not a third world country so why is the Senate considering something that will put us alongside them? Karen wall Melbourne, VIC 2015-03-09 How disgraceful that you would consider making it a crime to bring attention to any form of animal cruelty. -

AJP Policy Summaries and Key Objectives

Contents 1 Vision 1 3 Environment 15 3.1 Environment . 15 2 Animals 1 3.2 Climate Change . 16 2.1 Farming .............. 1 3.3 Natural Gas . 16 2.2 Companion Animals . 3 3.4 Wildlife And Sustainability . 17 2.3 Live Animal Exports . 4 3.5 Great Barrier Reef . 18 2.4 Animal Experimentation . 4 3.6 Land Clearing . 18 2.5 Bats And Flying Foxes . 5 4 Humans 19 2.6 Greyhound Racing . 6 2.7 Wombats ............. 6 4.1 Animal Law . 19 4.2 Biosecurity . 20 2.8 Brumbies ............. 7 4.3 Cultured Meat . 20 2.9 Dingo ............... 7 4.4 Economy . 21 2.10 Sharks ............... 8 4.5 Education . 22 2.11 Introduced Animals . 9 4.6 Employment . 22 2.12 Jumps Racing . 10 4.7 Family Violence . 23 2.13 Kangaroos . 10 4.8 Health . 23 2.14 Koalas . 11 4.9 Human Diet And Animals . 24 2.15 Native Birds . 11 4.10 International Affairs . 25 2.16 Marine Animals . 12 4.11 Law Social Justice . 25 2.17 Animals In Entertainment . 13 4.12 Mental Health . 26 2.18 Zoos . 14 4.13 Population . 26 . Introduction This is a compendium of new policy Summaries and Key Objectives flowing out of the work of various policy committees during 2016. Editing has been made in an attempt to ensure consistency of style and to remove detail which is considered unnecessary at this stage of our development as a political party. Policy development is an on-going process. If you have comments, criticisms or sugges- tions on policy please email [email protected]. -

Reading Animals and the Human-Animal Divide in Twenty-First Century Fiction

READING ANIMALS AND THE HUMAN-ANIMAL DIVIDE IN TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY FICTION Catherine Helen Parry A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Lincoln for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My wholehearted thanks to my supervisors Dr Rupert Hildyard and Dr Sîan Adiseshiah at the University of Lincoln. They were kind, thoughtful, and always right. I am also deeply grateful to Hilary Savory for friendship beyond the call of duty. Thank you to my daughters for their patience and support, and to Bonnie for her companionship throughout my doctoral studies. Most of all, thank you to Keith for making these writing years possible. 2 ABSTRACT The Western conception of the proper human proposes that there is a potent divide between humans and all other animate creatures. Even though the terms of such a divide have been shown to be indecisive, relationships between humans and animals continue to take place across it, and are conditioned by the ways it is imagined. My thesis asks how twenty-first century fiction engages with and practises the textual politics of animal representation, and the forms these representations take when their positions relative to the many and complex compositions of the human-animal divide are taken into account. My analysis is located in contemporary critical debate about human-animal relationships. Taking the animal work of such thinkers as Jacques Derrida and Cary Wolfe as a conceptual starting point, I make a detailed and precise engagement with the conditions and terms of literary animal representation in order to give forceful shape to awkward and uncomfortable ideas about animals. -

Animal Justice Party (AJP) National Committee

The POLICIES AND SUPPORTING INFORMATION IN THIS DOCUMENT ARE SUBJECT TO FREQUENT ANALYSIS AND CAN BE CHANGED AT ANY TIME BY THE Animal Justice Party (AJP) National Committee. Animal Justice Party Contents Climate Change................. Animals Animal Experimentation............ EnerGY...................... Animal Law.................... EnvirONMENT................... Animals IN Entertainment............ GrEAT Barrier Reef................ Bats And Flying FoXES.............. Land Clearing.................. Biosecurity.................... WASTE....................... BoW Hunting................... Wildlife And Sustainability........... Brumbies..................... Companion Animals Short........... Humans CulturED Meat.................. Dingo....................... Decent WORK................... Duck Shooting.................. Domestic Violence................ Farming...................... Economy..................... GrEYHOUND Racing................ Education..................... INTRODUCED Animals............... EmploYMENT................... Jumps Racing................... Genetic Manipulation.............. KangarOOS.................... Gun ContrOL................... Koalas....................... Health....................... Law Social Justice................ Human Diet And Animals............ Live Animal Exports............... INTERNATIONAL AffAIRS............... Marine Animals................. Mental Health.................. Native BirDS................... NaturAL Gas.................... Platypus.................... -

Great Spirits Have Always Encountered Violent Opposition from Mediocre Minds’ Albert Einstein P a G E 2

National Dingo Preservation and Recovery Program NDPRP MAGAZINE Winter, 2016 Volume 4 Number 1 NDPRP brings together a small number of well-informed and experienced people who strive to intervene strategically, advocating for the dingo using environmental and ecological research Contact Secretary Ernest Healy: [email protected] President Ian Gunn: [email protected] Vice President Jennifer Parkhurst: [email protected] Secondary Story Headline Incorporation No. A0051763G ‘Great spirits have always encountered violent opposition from mediocre minds’ Albert Einstein P a g e 2 Inside this Issue: President Report 3 Vic Priorities for 2016-17 4 NDPRP Activities/actions 2015-16 5 Joint letter to Minister—dingo reform 7 Victorian Ministerial meeting 9 Letter to Minister—Apex predator reform 10 Conference—Dingo meat to Asia 14 Feature Article—Blinded by Science 16 Pelorus Island—dingoes/goats 22 Marc Bekoff—Death Row Dingoes 24 Pelorus Island—UPDATE 26 The Inaugural NDPRP Excellence Award 28 Getting to know Simon 29 Bits and Pieces 30 Eagle’s Nest Wildlife Sanctuary 32 The Mt Buffalo dingo debate 34 Humane Society International 36 Fraser Island Report 40 AWPC—Kangaroos and Their Kin 48 Restoration of degraded woodland, SA 49 Membership form 50 Affiliate Organisations: Australian Dingo Conservation Association (NSW) Humane Society International (Aust) Save Fraser Island Dingoes (Qld) Gumbaya Park (Vic) Jennifer Parkhurst Australian Wildlife Protection Council (Vic) Compiled by Ernest Healy and Eagle’s Nest Wildlife Sanctuary Qld) Jennifer Parkhurst P a g e 3 President’s Report I wish to convey my thanks and appreciation to the support and commitment of all This story can fit 150our-200 words.members, to the Committee and especially so to the Vice President Jennifer Parkhurst and the Secretary Ernest Healy for achieving a successful year. -

JCAS Vol 18 Iss 2 May 2021 FINAL

V O L U M E 1 8 , I S S U E 2 Author ISSN 1948-352X Journal for Critical Animal Studies Editor Assistant Editor Dr. Amber E. George Nathan Poirier Galen University Michigan State University Peer Reviewers Michael Anderson Dr. Stephen R. Kauffman Drew University Christian Vegetarian Association Dr. Julie Andrzejewski Z. Zane McNeill St. Cloud State University Central European University Annie Côté Bernatchez Dr. Anthony J. Nocella II University of Ottawa Salt Lake Community College Amanda (Mandy) Bunten-Walberg Dr. Emily Patterson-Kane Queen’s University American Veterinary Medical Association Dr. Stella Capocci Montana Tech Dr. Nancy M. Rourke Canisius College Dr. Matthew Cole The Open University T. N. Rowan York University Sarat Colling Independent Scholar Jerika Sanderson Independent Scholar Christian Dymond Queen Mary University of London Monica Sousa York University Stephanie Eccles Concordia University Tayler E. Staneff University of Victoria Dr. Carrie P. Freeman Georgia State University Elizabeth Tavella University of Chicago Dr. Cathy B. Glenn Independent Scholar Dr. Siobhan Thomas London South Bank University David Gould University of Leeds Dr. Rulon Wood Boise State University Krista Hiddema Royal Roads University Allen Zimmerman Georgia State University William Huggins Independent Scholar Contents Issue Introduction: Critiques and Reimaginings of pp. 1-4 Anthropocentrism Essay: Anthropocentric Paradoxes in Cinema pp. 5-41 Ciannait Khan Essay: Mapping Parallel Ecological Constructs in Fish pp. 42-69 and Humans Abiodun Oluseye Essay: Surviving the Ends of Man: On the Animal pp. 70-99 and/as Black Gaze in Jordan Peele’s Get Out and Us M. Shadee Malaklou Essay: Hegemonic, Quasi-Counterhegemonic and pp. -

Profiles of the Signers of the 1849

rofiles P of the Signers of the 1849 California Constitution with Family Histories Compiled and edited by Wayne R. Shepard from original research by George R. Dorman With additional contributions from the members of the California Genealogical Society 2020 California Genealogical Society Copyright 2020 © California Genealogical Society California Genealogical Society 2201 Broadway, Suite LL2 Oakland, CA 94612-3031 Tel. (510) w663-1358 Fax (510) 663-1596 Email: [email protected] Website: https://www.californiaancestors.org/ Photographs of the signers courtesy of Colton Hall Museum, Monterey, California. Photograph of the signature page from the California Constitution courtesy of the California State Archives, Sacramento, California. CGS Contributors: Barbara E. Kridl Marie Treleaven Evan R. Wilson Lois Elling Stacy Hoover Haines Chris Pattillo Arlene Miles Jennifer Dix iii Contents Preface................................................................................................................... vii The 1849 California Constitutional Convention .................................................... ix Angeles District ...................................................................................................... 1 Jose Antonio Carrillo ........................................................................................ 3 Manuel Dominguez ......................................................................................... 11 Stephen Clark Foster ...................................................................................... -

Winchester Podiatry Charlesc D

The Sewanee Mountain VOL. XXVI No. 12 Thursday, March 25, 2010 Published as a public service for the Sewanee community since 1985. Singer/Songwriter F.C. Chamber Free Film Sunday: Michael Moore’s David Olney Business Expo “Capitalism: A Love Story” Friday at SAS Today Learn about the impact of corpo- corporations gambling on their rate dominance on everyday Amer- employees dying and pocketing mil- St. Andrew’s-Sewanee School The 18th annual Franklin County Chamber of Commerce Business ica at the free screening of Michael lions on life insurance policies when will host a free public concert by Moore’s new fi lm, “Capitalism: A Love they do, and neighborhoods where singer and songwriter David Olney Expo with the theme “Come Grow Your Business” is set for today, March Story,” on Sunday, March 28, at 7 p.m. nine out of 10 homes are empty due on Friday, March 26, at 7:30 p.m. in in the Sewanee Community Center. to job loss. McCrory Hall for the Performing 25, from 4 to 8 p.m. in the Monterey Station in Cowan. Admission is $2, With both humor and outrage, the “Capitalism: A Love Story” shows Arts. 127-minute fi lm explores the ques- what a more hopeful future could look Olney’s songs have been covered and tickets are available at the door. The expo boasts more than 100 tion: What is the price that America like. A discussion will follow the fi lm, by numerous artists, including pays for its love of capitalism? Moore inviting the community to explore Emmylou Harris, Linda Ronstadt, exhibitors in one location and more than 100 prizes, including the grand goes into the homes of ordinary ways to address the ills of capitalism Del McCoury and many others. -

Australian Politics in a Digital Age

Australian Politics in a Digital Age Peter John Chen Australian Politics in a Digital Age Peter John Chen Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Chen, Peter John. Title: Australian politics in a digital age / Peter John Chen. ISBN: 9781922144393 (pbk.) 9781922144409 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Information technology--Political aspects--Australia. Information technology--Social aspects--Australia. Internet--Political aspects--Australia. Information society--Social aspects--Australia. Communication--Political aspects--Australia. Dewey Number: 303.48330994 All rights reserved. Conditions of use of this volume can be viewed at the ANU E Press website. Cover image: Jonathon Chapman, Typographic Papercut Lampshade, http://www.flickr.com/ photos/jonathan_chapman1986/4004884667 Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2013 ANU E Press Contents List of illustrations . vii List of figures . ix List of tables . xi About the author . xiii Acknowledgements . xv Acronyms and jargon . .. xvii Chapter 1 — Contextualising our digital age . 1 Chapter 2 — Obama-o-rama? . 17 Chapter 3 — Social media . 69 Chapter 4 — Anti-social media . 113 Chapter 5 — All your base . 135 Chapter 6 — Elite digital media and digital media elites . 161 Chapter 7 — Policy in an age of information -

The Great Emu Wars

Cold Open: The Great Emu [ ee-myoo ] War! Not EE-MOOOO War - Eee MYOO War. I hear you Aussie Suckers. As World War I came to an end, Australia - whose economy was tanking, tried to figure out what to do with their returning veterans. They decided to give many of them parcels of land in Western Australia where they could grow wheat. And then the Great Depression hit. It hit countries all over the world, and few harder than Australia, and hit few Australians harder than many of those veteran farmers. They now struggled to sell their wheat. AND THEN - to make things EVEN WORSE - Emus [ ee-myoo ] started showing up. Lots of them. Around 20,000. And they were real hungry. And they figured out that wheat…. is PRETTY tasty. No gluten free diet for them. They wanted ALL the gluten. These new farmers were now being financially terrorized by a massive mob of Emus [ ee-myoos ]. And yes, a mob is the “technical” term for a group of Emus [ ee-myoo ]. These large flightless, strange-looking bumbling dinosaur birds tore through fences, ate crops, and sometimes, even attacked farmers - especially if they spotted a shiny object on them, like a coin or belt buckle. Australia’s national bird became a national pest. The “Emu [ ee-myoo ] infestation” got so bad that these desperate farmers reached out to the Australian government for help. In their quest for solutions, they skipped over the Agricultural or Ecology folks and even the Animal Management folks and went straight…… to the Ministry of WAR.