The Causal Role of the Somatosensory Cortex in Prosocial Behaviour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roots of Empathy RESEARCH SYMPOSIUM Toronto, Canada MAY 9-10, 2018 Proceedings

Roots of Empathy RESEARCH SYMPOSIUM Toronto, Canada MAY 9-10, 2018 PROCEEDINGS www.rootsofempathy.org www.rootsofempathy.org ROOTS OF EMPATHY RESEARCH SYMPOSIUM 2018 PROCEEDINGS Introduction The 2018 Roots of Empathy Research Symposium – our seventh – was another successful, inspiring and engaging gathering of renowned international scientists. One of the goals of Roots of Empathy is to expand and share research about the landscape of childhood. This symposium allowed researchers from around the world to gather in Ontario for two days of knowledge transfer to introduce their work to each other and begin research collaborations. This year we hosted researchers from the Netherlands, Iceland, Poland, United States, Switzerland, Canada and Finland. Dr. Brian Goldman of Toronto, author of The Power of Kindness: Why Empathy is Essential in Everyday Life, opened the symposium with his captivating story of empathy in medicine and his personal journey to becoming a better doctor. Graham Allen, former UK MP, Dr. Christian Keysers, Dr. Inga Dóra Sigfúsdóttir, Dr. Andrew Meltzoff, Dr. Ryszard Praszkier, Dr. David Lätsch, Elina Marjamäki and Mary Gordon shared research and insights on the neuroscience of empathy and social development, the origins of empathy as shown in the early connectedness between infants and adults, and interventions that have resulted in positive outcomes for children and youth. Each presentation was followed by a robust question and answer period with the audience and it was clear the presentations were thought provoking and needed. Roots of Empathy values the lens of research as the organization continues to provide empathy-based programming to children on three continents. We would like to thank the Ontario Ministry of Education for supporting the 2018 Roots of Empathy Research Symposium. -

Jidavis Embodiment and Emotion Symposium

UC Merced Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society Title How an Embodied Mind Perspective can Influence the Study of Emotion Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3j42685s Journal Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, 31(31) ISSN 1069-7977 Authors Davis, Joshua Keysers, Chrisitan Strack, Fritz et al. Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California How an Embodied Mind Perspective can Influence the Study of Emotion Joshua Ian Davis (jdavis at barnard.edu), Moderator Department of Psychology, Barnard College of Columbia University 3009 Broadway, New York, NY 10027, USA Christian Keysers (c.m.keysers at rug.nl) Department of Neuroscience, University Medical Center Groningen & BCN NeuroImaging Center, University of Groningen A. Deusinglaan 2, 9713AW Groningen, The Netherlands Fritz Strack (strack at psychologie.uni-wuerzburg.de) University of Würzburg LS Psychologie II, Röntgenring 10, 97070 Würzburg, Germany Jamil Zaki (jamil at psych.columbia.edu) Department of Psychology, Columbia University 1190 Amsterdam Avenue, New York, NY, 10027, USA Keywords: Embodied Mind, Embodied Cognition, Embodiment, accuracy). In particular, empathic accuracy has been shown Emotion, Affect, Empathy, Botox, Facial Feedback, when changes in skin conductance response for both Neuroimaging, Psychophysiology perceivers and targets are correlated over time (known as physiological linkage). This finding suggests that Embodied approaches to studying the mind have received embodying the states of others is an important route to increasing attention over the last decade (e.g. Barsalou, interpersonal understanding. We replicated and extended 2008; Damasio, 1999; Lakoff & Johnson, 1999; Niedenthal, this finding, illustrating how these effects depend on 2007). -

New Advances in Social Neuroscience: From

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Editorial overview: New advances in social neuroscience: from neural computations to social structures David M Amodio and Christian Keysers Current Opinion in Psychology 2019, 24:iv–vi For a complete overview see the Issue Available online 2nd November 2018 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.10.017 2352-250X/ã 2018 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1,2 David M Amodio We are delighted to present this special issue on Social Neuroscience, in which we feature some of the most exciting recent developments in this vibrant field. These developments reflect an important shift in social neuroscience research, from earlier interest in identifying brain regions that respond to particular social stimuli (i.e. the so-called ‘blobology’ approach), toward questions about the specific neural mechanisms that contribute to social cognition and behavior and their roles in broader contexts of human social interaction. These conceptual advances regarding mechanism have been made by 1 Department of Psychology, New York focusing on two central questions: first what computations are performed University, 6 Washington Place, New York, in specific brain networks and second how do they causally contribute to 2 NY, 10003, USA Department of Psychology, social behavior? These questions are central both to neuroscience and social University of Amsterdam, Nieuwe Achtergracht cognition. Neuroscience seeks to understand how the brain works, and given 129 B, P.O. Box 15900, 1001 NK, Amsterdam, The Netherlands that the human brain evolved in a context where social functioning pro- e-mail: [email protected] moted survival, social computations are often key to deciphering the operations of the brain. -

Journal.Pbio.3000524-1

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Bidirectional cingulate-dependent danger information transfer across rats Han, Y.; Bruls, R.; Soyman, E.; Thomas, R.M.; Pentaraki, V.; Jelinek, N.; Heinemans, M.; Bassez, I.; Verschooren, S.; Pruis, I.; Van Lierde, T.; Carrillo, N.; Gazzola, V.; Carrillo, M.; Keysers, C. DOI 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000524 Publication date 2019 Document Version Final published version Published in PLoS Biology License CC BY Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Han, Y., Bruls, R., Soyman, E., Thomas, R. M., Pentaraki, V., Jelinek, N., Heinemans, M., Bassez, I., Verschooren, S., Pruis, I., Van Lierde, T., Carrillo, N., Gazzola, V., Carrillo, M., & Keysers, C. (2019). Bidirectional cingulate-dependent danger information transfer across rats. PLoS Biology, 17(12), [e3000524]. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000524 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. -

Intracortical Human Recordings Reveal Intensity Coding for the Pain of Others in the Insula

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.23.449371; this version posted June 24, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Intracortical human recordings reveal intensity coding for the pain of others in the insula Efe Soyman,1,2,† Rune Bruls,1,† Kalliopi Ioumpa,1,† Laura Müller-Pinzler,3 Selene Gallo,1,4 Elisabeth C.W. van Straaten,5 Matthew W. Self,6 Judith C. Peters,6,7,8 Jessy K. Possel,6 Yoshiyuki Onuki,9 Johannes C. Baayen,10 Sander Idema,10 Christian Keysers1,11,‡ and Valeria Gazzola1,11,‡ †,‡These authors contributed equally to this work. Author affiliations: 1 Social Brain Lab, Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience, Royal Netherlands Academy of Art and Sciences, 1105 BA, Amsterdam, the Netherlands 2 Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience Lab, Kadir Has University, Cibali 34083, Fatih, Istanbul, Turkey 3 Social Neuroscience Lab, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Lübeck, 23562, Lübeck, Germany 4 Department of Psychiatry, Amsterdam University Medical Center, 1105 AZ, Amsterdam, the Netherlands 5 Department of Neurology and Clinical Neurophysiology, Amsterdam UMC, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, 1117 HV, Amsterdam, the Netherlands 6 Department of Vision and Cognition, Netherlands Institute of Neuroscience, Royal Netherlands Academy of Art and Sciences, 1105 BA, Amsterdam, the Netherlands 7 Department of Cognitive Neuroscience, Faculty of Psychology and Neuroscience, Maastricht -

Somatosensation in Social Perception

REVIEWS Somatosensation in social perception Christian Keysers*‡, Jon H. Kaas§ and Valeria Gazzola*‡ Abstract | The discovery of mirror neurons in motor areas of the brain has led many to assume that our ability to understand other people’s behaviour partially relies on vicarious activations of motor cortices. This Review focuses the limelight of social neuroscience on a different set of brain regions: the somatosensory cortices. These have anatomical connections that enable them to have a role in visual and auditory social perception. Studies that measure brain activity while participants witness the sensations, actions and somatic pain of others consistently show vicarious activation in the somatosensory cortices. Neuroscientists are starting to understand how the brain adds a somatosensory dimension to our perception of other people. Vicarious activation One of the most exciting developments of the past expressions such as “Her words were really touch- Activation of a brain region that decade is the discovery that our perception of other ing” encapsulate the intuitive link between the people is normally involved in individuals involves neurons and brain areas that were around us and our sense of touch. processing the observer’s own thought to be reserved for the control of our own In this Review, we first describe the location and con- actions and sensations, but (FIG. 1) that is now activated by seeing actions and the experience of our own emotions. First, nections of the somatosensory cortices to show similar actions or sensations in it became clear that seeing or hearing other people’s that, in contrast to the early somatosensory cortices in another person. -

Los Angeles, California March 16-18, 2017 10Th Annual Meeting

10th Annual Meeting Los Angeles, California March 16-18, 2017 Social & Affective Neuroscience Society Annual Meeting 2017 March 16-18 | University of California, Los Angeles Conference Chairs Naomi Eisenberger, University of California, Los Angeles Matthew Lieberman, University of California, Los Angeles Carolyn Parkinson, University of California, Los Angeles Jennifer Silvers, University of California, Los Angeles Program Committee Molly Crockett, Yale University Dominic Fareri, Adelphi University Chad Forbes, University of Delaware (Committee co-chair) Jonathan Freeman, New York University Nicole Giuliani, University of Oregon Johanna Jarcho, Stony Brook University Hedy Kober, Yale University Liz Losin, University of Miami Dean Mobbs, CalTech Kyle Ratner, University of California, Santa Barbara Daniela Schiller, Mount Sinai School of Medicine (Committee co-chair) Damian Stanley, Adelphi University Diana Tamir, Princeton University Dylan Wagner, The Ohio State University SANS Executive Committee Paul Whalen, President Mauricio Delgado, President-Elect Elizabeth Phelps, Past-President Kateri McRae, Secretary Emily Falk, Treasurer Lauren Atlas, Member-at-Large Mina Cikara, Member-at-Large Jamil Zaki, Member-at-Large Oriel FeldmanHall, Social Media Chair Conference Schedule Thursday, March 16 Start End Session 12:00 PM 2:45 PM Registration 2:45 PM 3:00 PM Opening Remarks 3:00 PM 4:15 PM Symposium Session 1: Social and Affective Decision Making Brian Knutson: From brain to internet: Neuroforecasting social preferences Hedy Kober: Mindfulness-based -

FIVE Myths About the Role of Culture in Psychological Research

What Should Our Scientific Discourse Look Like? ObserverVol. 30, No. 1 January 2017 FIVE Myths About the Role of Culture in Psychological Research a publication of www.psychologicalscience.org/observer Integrative Science Symposia 23-25 March 2017 | Vienna, Austria Our Social Brain: Neurobiology Emotions in Context Bridging the Lab and the of Human Interactions Ralph Adolphs, Division of the Real World Christian Keysers, Social Brain Lab, Humanities and Social Sciences, Karen E. Adolph, Department of Early Price Registration | 15 February Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience, California Institute of Technology, USA Psychology, New York University, USA Register Now to Get the Best Rates and Department of Psychology, University Iris M. Engelhard, Department of Rick Dale, Department of Cognition of Amsterdam, The Netherlands Psychology, Utrecht University, & Information Sciences, University of Brian D. Knutson, Department of The Netherlands California, Merced, USA Psychology and Neuroscience, Stanford Klaus R. Scherer, Department of Susan Goldin-Meadow, Department University, USA Psychology, University of Geneva, of Comparative Human Development, KEYNOTE SPEAKERS Rebecca Saxe, Department of Brain and Switzerland (Discussant) The University of Chicago, USA Cognitive Sciences, Massachusetts Institute Jeanne L. Tsai, Department of Emiliano Macaluso, Impact Team, of Technology, USA Psychology, Stanford University, USA Lyon Neuroscience Research Center, Frank H. Wilhelm, Department of France Who’s In, Who’s Out? Loneliness, Clinical Psychology -

Curriculum Vitae

CV - GRS: 1 CURRICULUM VITAE Name Gün Refik Surname SEMIN Nationality British Home Address Flevolaan 30) 1411 KD Naarden The Netherlands Tel. & Fax +31-35-6948580 Office Address Faculty of Social Sciences Utrecht University, Heidelberglaan 1, 3584 CS Utrecht, The Netherlands Tel. +31-30-2534575 Secretary: +31-30-2531470 Fax. +31-30-2534718 email [email protected] Education Deutsche Oberrealschule, Istanbul, Turkey (1963) Albert Ludwigs Universität, Freiburg i. Br, FRG (1964 -1965, Major in Psychology) Freie Universität Berlin, West Berlin (1965 -1968, Major in Psychology) London School of Economics and Political Science University of London (1969 - 1972) Degrees German Abitur and Turkish Lycee, 1963 Deutsche Oberrealschule, Istanbul Vordiplom für Psychologie, Freie Universität Berlin - (23.11.1966) Diplom für Psychologie, Freie Universität Berlin - (11.11.1968) Ph.D. in Social Psychology, LSE, University of London (22.1.1974) Languages Fluent in the following languages: English, Turkish, German, Dutch, and some French CV - GRS: 2 Awards “Officier in de Orde van Oranje-Nassau”, April 27, 2012 Society for Personality and Social Psychology 2005 ‘Theoretical Innovation Prize’ for “Smith, E. R. & Semin, G. R. (2004). Socially situated cognition: Cognition in its social context. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 36, 53-117 Academy Professor, the Royal Netherlands Academy for Arts and Sciences program for outstanding senior researchers (2004-). Misumi Award from the Japanese Group Dynamics Association and the Asian Association of Social Psychology-2001. Uleman, J., Rhee, E., Bardoliwalla, N., Semin, G. R., & Toyama, M. (2000). The relational self: Closeness to in-groups depends on who they are, culture, and the type of closeness. -

Christian Keysers - Selected References

Christian Keysers - selected references 1 Keysers, C. & Gazzola, V. (2014). Hebbian learning and predictive mirror neurons for actions, sensations and emotions. Philos.Trans.R.Soc.Lond B Biol.Sci., 369, 20130175. Notes: Spike-timing-dependent plasticity is considered the neurophysiological basis of Hebbian learning and has been shown to be sensitive to both contingency and contiguity between pre- and postsynaptic activity. Here, we will examine how applying this Hebbian learning rule to a system of interconnected neurons in the presence of direct or indirect re-afference (e.g. seeing/hearing one's own actions) predicts the emergence of mirror neurons with predictive properties. In this framework, we analyse how mirror neurons become a dynamic system that performs active inferences about the actions of others and allows joint actions despite sensorimotor delays. We explore how this system performs a projection of the self onto others, with egocentric biases to contribute to mind-reading. Finally, we argue that Hebbian learning predicts mirror-like neurons for sensations and emotions and review evidence for the presence of such vicarious activations outside the motor system 2 Keysers, C. & Gazzola, V. (2014). Dissociating the ability and propensity for empathy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18, 163-166. Notes: Neuroimaging suggests psychopaths have reduced vicarious activations when simply witnessing pain but less so when asked to empathize. This inspired us to distinguish the ability from the propensity to empathize. We argue that (i) this ability-propensity distinction is crucial to characterizing empathy in psychiatric disorders such as psychopathy and autism, (ii) that costly helping might be best predicted by the propensity for empathy, and (iii) suggest how social neuroscientists can start exploring this distinction 3 Keysers, C., Perrett, D. -

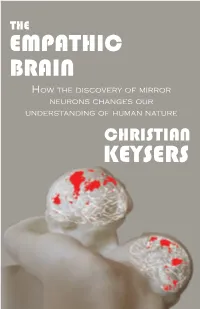

The Empathic Brain How the Discovery of Mirror Neurons Changes Our Understanding of Human Nature Christian Keysers

THE EMPATHIC BRAIN HOW THE DISCOVERY OF MIRROR NEURONS CHANGES OUR UNDERSTANDING OF HUMAN NATURE CHRISTIAN KEYSERS The Empathic Brain How the discovery of mirror neurons changes our understanding of human nature Christian Keysers First Published June 2011 as a Kindle E-Book Copyright © 2011 Christian Keysers All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any mean, without the prior permission in writing of the author. Cover and book designed by Christian Keysers, in-text illustrations by Valeria Gazzola. About The Cover: Le Baiser by Rodin is my favorite sculpture. The symmetry of two lovers’ kiss is a metaphor for our brain’s capacity to mirror people’s actions, sensations and emotions. The fusion, in love, of two souls epitomizes the empathic brain – and marked the start of the most meaningful experience of my life. To Julia Contents Introduction: Connecting People 7 1 . The Discovery of Mirror Neurons 13 2. The Power of Intuition 29 3. Human Mirroring 37 4. Born to Socialize 53 5. Language 67 6. Sharing Emotions 91 7. Sensations 119 8. Learning to Share 137 9. Autism and Misunderstandings 161 10. A Unifying Theory of Social Cognition 181 11. Empathic Ethics 193 Epilogue: Mirror Neurons, Good or Bad? 221 Acknowledgements 225 Map of the Empathic Brain 226 Endnotes 229 Bibliography 231 About the Author 241 Appendix: Interpersonal Reactivity Index 242 Introduction: Connecting People he best day of my life started off with what you could call a failure. Even little details of that moment will stay in my head T forever. -

The Causal Role of the Somatosensory Cortex in Prosocial Behaviour

RESEARCH ARTICLE The causal role of the somatosensory cortex in prosocial behaviour Selene Gallo1, Riccardo Paracampo1,2,3, Laura Mu¨ ller-Pinzler1,4, Mario Carlo Severo1‡, Laila Blo¨ mer1†, Carolina Fernandes-Henriques1†, Anna Henschel1†, Balint Kalista Lammes1†, Tatjana Maskaljunas1†, Judith Suttrup1, Alessio Avenanti2,3, Christian Keysers1,5, Valeria Gazzola1,5* 1Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience, Royal Netherlands Academy of Art and Sciences (KNAW), Amsterdam, Netherlands; 2Department of Psychology, Center for Studies and Research in Cognitive Neuroscience, University of Bologna, Cesena, Italy; 3IRCCS Fondazione Santa Lucia, Rome, Italy; 4Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Social Neuroscience Lab, University of Lu¨ beck, Lu¨ beck, Germany; 5Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands Abstract Witnessing another person’s suffering elicits vicarious brain activity in areas that are active when we ourselves are in pain. Whether this activity influences prosocial behavior remains the subject of debate. Here participants witnessed a confederate express pain through a reaction of the swatted hand or through a facial expression, and could decide to reduce that pain by donating money. Participants donate more money on trials in which the confederate expressed *For correspondence: more pain. Electroencephalography shows that activity of the somatosensory cortex I (SI) hand [email protected] region explains variance in donation. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) shows that altering † These authors contributed this activity interferes with the pain–donation coupling only when pain is expressed by the hand. equally to this work High-definition transcranial direct current stimulation (HD-tDCS) shows that altering SI activity also Present address: ‡Department interferes with pain perception.