Pre-Colonial Religious Institutions and Development: Evidence Through a Military Coup∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Map (PDF | 4.45

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Overview - PUNJAB ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! K.P. ! ! ! ! ! ! Murree ! Tehsil ! ! ! ! ! ! Hasan Abdal Tehsil ! Attock Tehsil ! Kotli Sattian Tehsil ! Taxila Tehsil ! ! ! ! ! ! Attock ! ! ! ! Jand Tehsil ! Kahuta ! Fateh Jang Tehsil Tehsil ! ! ! Rawalpindi Tehsil ! ! ! Rawalpindi ! ! Pindi Gheb Tehsil ! J A M M U A N D K A S H M I R ! ! ! ! Gujar Khan Tehsil ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Sohawa ! Tehsil ! ! ! A F G H A N I S T A N Chakwal Chakwal ! ! ! Tehsil Sarai Alamgir Tehsil ! ! Tala Gang Tehsil Jhelum Tehsil ! Isakhel Tehsil ! Jhelum ! ! ! Choa Saidan Shah Tehsil Kharian Tehsil Gujrat Mianwali Tehsil Mianwali Gujrat Tehsil Pind Dadan Khan Tehsil Sialkot Tehsil Mandi Bahauddin Tehsil Malakwal Tehsil Phalia Mandi Bahauddin Tehsil Sialkot Daska Tehsil Khushab Piplan Tehsil Tehsil Wazirabad Tehsil Pasrur Tehsil Narowal Shakargarh Tehsil Shahpur Tehsil Khushab Gujranwala Bhalwal Hafizabad Tehsil Gujranwala Tehsil Tehsil Narowal Tehsil Sargodha Kamoke Tehsil Kalur Kot Tehsil Sargodha Tehsil Hafizabad Nowshera Virkan Tehsil Pindi Bhattian Tehsil Noorpur Sahiwal Tehsil Tehsil Darya Khan Tehsil Sillanwali Tehsil Ferozewala Tehsil Safdarabad Tehsil Sheikhupura Tehsil Chiniot -

Muzaffargarh

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! Overview - Muzaffargarh ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Bhattiwala Kherawala !Molewala Siwagwala ! Mari PuadhiMari Poadhi LelahLeiah ! ! Chanawala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ladhranwala Kherawala! ! ! ! Lerah Tindawala Ahmad Chirawala Bhukwala Jhang Tehsil ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Lalwala ! Pehar MorjhangiMarjhangi Anwarwal!a Khairewala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Wali Dadwala MuhammadwalaJindawala Faqirewala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! MalkaniRetra !Shah Alamwala ! Bhindwalwala ! ! ! ! ! Patti Khar ! ! ! Dargaiwala Shah Alamwala ! ! ! ! ! ! Sultanwala ! ! Zubairwa(24e6)la Vasawa Khiarewala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Jhok Bodo Mochiwala PakkaMochiwala KumharKumbar ! ! ! ! ! ! Qaziwala ! Haji MuhammadKhanwala Basti Dagi ! ! ! ! ! Lalwala Vasawa ! ! ! Mirani ! ! Munnawala! ! ! Mughlanwala ! Le! gend ! Sohnawala ! ! ! ! ! Pir Shahwala! ! ! Langanwala ! ! ! ! Chaubara ! Rajawala B!asti Saqi ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! BuranawalaBuranawala !Gullanwala ! ! ! ! ! Jahaniawala ! ! ! ! ! Pathanwala Rajawala Maqaliwala Sanpalwala Massu Khanwala ! ! ! ! ! ! Bhandniwal!a Josawala ! ! Basti NasirBabhan Jaman Shah !Tarkhanwala ! !Mohanawala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Basti Naseer Tarkhanwala Mohanawala !Citiy / Town ! Sohbawala ! Basti Bhedanwala ! ! ! ! ! ! Sohaganwala Bhurliwala ! ! ! ! Thattha BulaniBolani Ladhana Kunnal Thal Pharlawala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ganjiwala Pinglarwala Sanpal Siddiq Bajwa ! ! ! ! ! Anhiwala Balochanwala ! Pahrewali ! ! Ahmadwala ! ! ! -

Code Name Cnic No./Passport No. Name Address

Format for Reporting of Unclaimed Deposits. Instruments Surrendered to SBP Period of Surrendered (2016): Bank Code: 1279 Bank Name : THE PUNJAB PROVINCIAL COOPERATIVE BANK LIMITED HEAD OFFICE LAHORE Last date of DETAIL OF THE BRANCH NAME OF THE PROVINCE IN DETAIL OF THE DEPOSTOER BENEFICIARY OF THE INSTRUMENT DETAIL OF THE ACCOUNT DETAIL OF THE INSTRUMENT TRANSACTION deposit or WHICH ACCOUNT NATURE ACCOUNT Federal. Curren Rate FCS Rat Rate NAME OF THE INSTRUMENT Remarks S.NO CNIC NO./PASSPORT OF THE TYPE ( e.g INSTRUME DATE OF Provincial cy Type. Contract e Appli Amount Eqr. PKR withdrawal CODE NAME OPENED.INSTRUMENT NAME ADDRESS ACCOUNT NUMBER APPICANT. TYPE (DD, PO, NO. DEPOSIT CURRENT NT NO. ISSUE (FED.PRO)I (USD, ( No (if of ed Outstanding surrendered (DD-MON- PAYABLE PURCHASER FDD, TDR, CO) (LCY,UF , SAVING , n case of EUR, MTM, any) PK date YYYY) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 1 321 SAHIWAL DC PB 36502-8695206-3 KAMAL-UD-DIN S.O ALLAH BUKHSH ARCS SAHIWAL, TEHSIL & DISTRICT SAHIWAL LCY 15400100011001 PLS PKR 1,032.00 1,032.00 18/07/2005 2 321 SAHIWAL DC PB 36502-8795426-9 ALI MUHAMMAD S.O IMAM DIN H. NO. 196 FAREED TOWN SAHIWAL,TEHSIL & DISTRICT SAHIWAL LCY 15400100011101 PLS PKR 413.00 413.00 11/07/2005 3 321 SAHIWAL DC PB 36502-8395698-7 MUHAMMAD SALEEM CHAK NO. 80.6-R TEHSIL & DISTRICT SAHIWAL LCY 15400100011301 PLS PKR 1,656.00 1,656.00 08/03/2005 4 321 SAHIWAL DC PB 36502-3511981-9 ABDUL GHANI S.O ALLAH DITTA FARID TOWN 515.K ,TEHSIL & DISTRICT SAHIWAL LCY 15400100011501 PLS PKR 942.00 942.00 04/11/2005 5 321 SAHIWAL DC PB 36502-9956978-9 SHABBIR AHMAD S.O MUHAMMAD RAMZAN CHAK NO. -

Population According to Religion, Tables-6, Pakistan

-No. 32A 11 I I ! I , 1 --.. ".._" I l <t I If _:ENSUS OF RAKISTAN, 1951 ( 1 - - I O .PUlA'TION ACC<!>R'DING TO RELIGIO ~ (TA~LE; 6)/ \ 1 \ \ ,I tin N~.2 1 • t ~ ~ I, . : - f I ~ (bFICE OF THE ~ENSU) ' COMMISSIO ~ ER; .1 :VERNMENT OF PAKISTAN, l .. October 1951 - ~........-.~ .1',l 1 RY OF THE INTERIOR, PI'ice Rs. 2 ~f 5. it '7 J . CH I. ~ CE.N TABLE 6.-RELIGION SECTION 6·1.-PAKISTAN Thousand personc:. ,Prorinces and States Total Muslim Caste Sch~duled Christian Others (Note 1) Hindu Caste Hindu ~ --- (l b c d e f g _-'--- --- ---- KISTAN 7,56,36 6,49,59 43,49 54,21 5,41 3,66 ;:histan and States 11,54 11,37 12 ] 4 listricts 6,02 5,94 3 1 4 States 5,52 5,43 9 ,: Bengal 4,19,32 3,22,27 41,87 50,52 1,07 3,59 aeral Capital Area, 11,23 10,78 5 13 21 6 Karachi. ·W. F. P. and Tribal 58,65 58,58 1 2 4 Areas. Districts 32,23 32,17 " 4 Agencies (Tribal Areas) 26,42 26,41 aIIjab and BahawaJpur 2,06,37 2,02,01 3 30 4,03 State. Districts 1,88,15 1,83,93 2 19 4,01 Bahawa1pur State 18,22 18,08 11 2 ';ind and Kbairpur State 49,25 44,58 1,41 3,23 2 1 Districts 46,06 41,49 1,34 3,20 2 Khairpur State 3,19 3,09 7 3 I.-Excluding 207 thousand persons claiming Nationalities other than Pakistani. -

List of Canidates for Recuritment of Mali at Police College Sihala

LIST OF CANIDATES FOR RECURITMENT OF MALI AT POLICE COLLEGE SIHALA not Sr. No Sr. Name Address CNIC No CNIC age on07-04-21age Remarks Attached Qulification Date ofBirth Date Father Name Father Appliedin Quota AppliedPost forthe Date ofTestPractical Date Home District-DomicileHome Affidavit attached / Not Not Affidavit/ attached Day Month Year Experienceor Certificate attached 1 Ghanzafar Abbas Khadim Hussain Chak Rohacre Teshil & Dist. Muzaffargarh Mali Open M. 32304-7071542-9 Middle 01-01-86 7 4 35 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 W. No. 2 Mohallah Churakil Wala Mouza 2 Mohroz Khan Javaid iqbal Pirhar Sharqi Tehsil Kot Abddu Dist. Mali Open M. 32303-8012130-5 Middle 12-09-92 26 7 28 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Muzaffargarh Ghulam Rasool Ward No. 14 F Mohallah Canal Colony 3 Muhammad Waseem Mali Open M. 32303-6730051-9 Matric 01-12-96 7 5 24 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Khan Tehsil Kot Addu Dist. Muzaffargrah Muhammad Kamran Usman Koryia P-O Khas Tehsil & Dist. 4 Rasheed Ahmad Mali Open M. 32304-0582657-7 F.A 01-08-95 7 9 25 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Rasheed Muzaffargrah Muhammad Imran Mouza Gul Qam Nashtoi Tehsil &Dist. 5 Ghulam Sarwar Mali Open M. 32304-1221941-3 Middle 12-04-88 26 0 33 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Sarwar Muzaffargrah Nohinwali, PO Sharif Chajra, Tehsil 7 6 Mujahid Abbas Abid Hussain Mali Open M. 32304-8508933-9 Matric 02-03-91 6 2 30 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 District Muzaffargarh. Hafiz Ali Chah Suerywala Pittal kot adu, Tehsil & 7 Muhammad Akram Mali Disable 32303-2255820-5 Middle 01-01-82 7 4 39 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Mumammad District Muzaffargarh. -

Crop Damage Assessment Along the Indus River

0 1 0 2 K t A 0 s -P . u 1 2 g 4 n 1 u 0 io A 0 rs 0 -0 e 2 0 V 1 0 -2 L F " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " "" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " !( " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " !(" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " "" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " p " " " " " " " p " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " "" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " : " " " " " " " !( " " " " " " " " " " " y " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " b " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " d " " " " " " " " " " " " " !( " " e " " " " " " " " " " t " "" " "p " " " " " " " " " " r " !( " " " " !( " " " " !( " " " p " " " " " " " o " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " p " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " p " " " " " "" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " u " " " " " " " " " " t " " " !( " " " S " " " . " " " " " " " " " " o " " " " " " n " " " " " " " " " " " " " " D" " p " " " nn " " " " " " " " " !( " " " " e " " " " " " " " " " " " r O " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " a M " " " " " " " " " " I " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " e " " " " " " " " " aa " " " !( !(r C " " " " " " " " I " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " e " " " " " " " " " e L " " " p" " " " " " " " h I " " " " " " " " " tt "" -

Spatio-Temporal Flood Analysis Along the Indus River, Sindh, Punjab

p !( !( 23 August 2010 !( FL-2010-000141-PAK S p a t i o - Te m p o r a l F!( lo o d A n a l y s i s a l o n g t h e I n d u s R i v e r, S i n d h , P u n j a b , K P K a n d B a l o c h i s t a n P r o v i n c e s , P a k i s t a n p Version 1.0 !( This map shows daily variation in flo!(od water extent along the Indus rivers in Sindph, Punjab, Balochistan and KPK Index map CHINA p Crisis Satellite data : MODIS Terra / Aqua Map Scale for 1:1,000,000 Map prepared by: Supported by: provinces based on time-series MODIS Terra and Aqua datasets from August 17 to August 21, 2010. Resolution : 250m Legend 0 25 50 100 AFGHANISTAN !( Image date : August 18-22, 2010 Result show that the flood extent isq® continously increasing during the last 5 days as observed in Shahdad Kot Tehsil p Source : NASA Pre-Flood River Line (2009) Kilometres of Sindh and Balochistan provinces covering villages of Shahdad, Jamali, Rahoja, Silra. In the Punjab provinces flood has q® Airport p Pre-flood Image : MODIS Terra / Aqua Map layout designed for A1 Printing (36 x 24 inch) !( partially increased further in Shujabad Tehsil villages of Bajuwala Ti!(bba, Faizpur, Isanwali, Mulana)as. Over 1000 villages !( ® Resolution : 250m Flood Water extent (Aug 18) p and 100 towns were identified as severly affepcted by flood waters and vanalysis was performed using geospatial database ® Heliport !( Image date : September 19, 2009 !( v !( Flood Water extent (Aug 19) ! received from University of Georgia, google earth and GIS data of NIMA (USGS). -

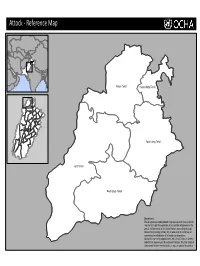

Reference Map

Attock ‐ Reference Map Attock Tehsil Hasan Abdal Tehsil Punjab Fateh Jang Tehsil Jand Tehsil Pindi Gheb Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. Bahawalnagar‐ Reference Map Minchinabad Tehsil Bahawalnagar Tehsil Chishtian Tehsil Punjab Haroonabad Tehsil Fortabbas Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. p Bahawalpur‐ Reference Map Hasilpur Tehsil Khairpur Tamewali Tehsil Bahawalpur Tehsil Ahmadpur East Tehsil Punjab Yazman Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

33422717.Pdf

1 Contents 1. PREFACE ........................................................................................................................................... 4 2. OVERVIEW OF THE CULTURAL ASSETS OF THE COMMUNITIES OF DISTRICTS MULTAN AND BAHAWALPUR ................................................................... 9 3. THE CAPITAL CITY OF BAHAWALPUR AND ITS ARCHITECTURE ............................ 45 4. THE DECORATIVE BUILDING ARTS ....................................................................................... 95 5. THE ODES OF CHOLISTAN DESERT ....................................................................................... 145 6. THE VIBRANT HERITAGE OF THE TRADITIONAL TEXTILE CRAFTS ..................... 165 7. NARRATIVES ................................................................................................................................... 193 8. AnnEX .............................................................................................................................................. 206 9. GlossARY OF TERMS ................................................................................................................ 226 10. BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................................. 234 11. REPORTS .......................................................................................................................................... 237 12 CONTRibutoRS ............................................................................................................................ -

Power Distribution Enhancement Investment Program – Tranche 4

Resettlement Plan Due Diligence June 2013 MFF 0021-PAK: Power Distribution Enhancement Investment Program – Tranche 4 Prepared by Multan Electric Power Company for the Asian Development Bank. This is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Due Diligence Document Document Stage: Final Project Number: M1-M64 {June 2013} Islamic Republic of Pakistan: Multitranche Financing Facility (MFF) For Power Distribution Enhancement Investment Program Tranche-IV: Power Transformer’s Extension & Augmentation Subprojects Prepared by: Environment & Social Safeguards Section Project Management Unit (PMU) MEPCO, Pakistan i Table of contents ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................................................................ iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................................. iv 1. Project Overview ................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Background ...................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Scope of Land Acquisition and Resettlement ................................................................................................. -

Punjab Health Statistics 2019-2020.Pdf

Calendar Year 2020 Punjab Health Statistics HOSPITALS, DISPENSARIES, RURAL HEALTH CENTERS, SUB-HEALTH CENTERS, BASIC HEALTH UNITS T.B CLINICS AND MATERNAL & CHILD HEALTH CENTERS AS ON 01.01.2020 BUREAU OF STATISTICS PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT BOARD GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB, LAHORE www.bos.gop.pk Content P a g e Sr. No. T i t l e No. 1 Preface I 2 List of Acronym II 3 Introduction III 4 Data Collection System IV 5 Definitions V 6 List of Tables VI 7 List of Figures VII Preface It is a matter of pleasure, that Bureau of Statistics, Planning & Development Board, Government of the Punjab has took initiate to publish "Punjab Health Statistics 2020". This is the first edition and a valuable increase in the list of Bureau's publication. This report would be helpful to the decision makers at District/Tehsil as well as provincial level of the concern sector. The publication has been formulated on the basis of information received from Director General Health Services, Chief Executive Officers (CEO’s), Inspector General (I.G) Prison, Auqaf Department, Punjab Employees Social Security, Pakistan Railways, Director General Medical Services WAPDA, Pakistan Nursing Council and Pakistan Medical and Dental Council. To meet the data requirements for health planning, evaluation and research this publication contain detailed information on Health Statistics at the Tehsil/District/Division level regarding: I. Number of Health Institutions and their beds’ strength II. In-door & Out-door patients treated in the Health Institutions III. Registered Medical & Para-Medical Personnel It is hoped that this publication would prove a useful reference for Government departments, private institutions, academia and researchers. -

Augmentation of MEPCO Sub-Projects

Initial Environmental Examination October 2012 MFF 0021-PAK: Power Distribution Enhancement Investment Program – Proposed Tranche 3 Prepared by the Multan Electric Power Company for the Asian Development Bank. Draft Initial Environmental Examination (IEE) Report Loan-Pak {October-2012} Islamic Republic of Pakistan: Power Distribution Enhancement Investment Program (Multi Tranche Financing Facility) Tranche-III: Augmentation of MEPCO Sub-Projects Prepared by: Multan Electric Power Company (MEPCO) Government of Pakistan The Initial Environmental Examination (IEE) Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB‟s Board of Directors, management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Overview 1 1.2 Requirements for Environmental Assessment 1 1.3 Scope of the IEE Study and Personnel 4 1.4 Policy and Statutory Requirements in Pakistan 4 1.5 National Environmental Quality Standards 5 1.6 Structure of Report 5 2. DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT 6 2.1 Type of Project 6 2.2 Categorization of the Project 7 2.3 Need for the Project 7 2.4 Location and Scale of Project 7 2.5 MEPCO Subprojects 7 3. DESCRIPTION OF THE ENVIRONMENT 11 3.1 Sub-project Areas 11 3.2 Physical Resources 11 3.2.1 Topography, Geography, Geology, and Soils 11 3.2.2 Climate and Hydrology 11 3.2.3 Groundwater and Water Supply Resources 11 3.2.4 Surface Water Resources 12 3.2.5 Air Quality 12 3.2.6 Noise and Vibration 13 3.3 Ecological Resources 13 3.4 Economic Development 13 3.5 Social and Cultural Resources 14 3.5.1 Administrative Setup 14 3.5.2 Population and Communities 14 3.5.3 Education and Literacy 15 3.5.4 Health Facilities 15 4.