Islanders Blame Nuyoricans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Latin(O) Americanos: Transoceanic Diasporas And

DEBATES: GLOBAL LATIN(O) AMERICANOS Global Latin(o) Americanos: Transoceanic Diasporas and Regional Migrations by MARK OVERMYER-VELÁZQUEZ | University of Connecticut | [email protected] and ENRIQUE SEPÚLVEDA | University of Saint Joseph, Connecticut | [email protected] Human mobility is a defining characteristic By the end of the first decade of the Our use of the term “Global Latin(o) of our world today. Migrants make up one twenty-first century the contribution of Americanos” places people of Latin billion of the globe’s seven billion people— Latin America and the Caribbean to American and Caribbean origin in with approximately 214 million international migration amounted to over comparative, transnational, and global international migrants and 740 million 32 million people, or 15 percent of the perspectives with particular emphasis on internal migrants. Historic flows from the world’s international migrants. Although migrants moving to and living in non-U.S. Global South to the North have been met most have headed north of the Rio Grande destinations.5 Like its stem words, Global in equal volume by South-to-South or Rio Bravo and Miami, in the past Latin(o) Americanos is an ambiguous term movement.1 Migration directly impacts and decade Latin American and Caribbean with no specific national, ethnic, or racial shapes the lives of individuals, migrants have traveled to new signification. Yet by combining the terms communities, businesses, and local and destinations—both within the hemisphere Latina/o (traditionally, people of Latin national economies, creating systems of and to countries in Europe and Asia—at American and Caribbean origin in the socioeconomic interdependence. -

Latino Unemployment Rate Remains the Highest at 17.6% Latina Women Are Struggling the Most from the Economic Fallout

LATINO JOBS REPORT JUNE 2020 Latino Unemployment Rate Remains the Highest at 17.6% Latina women are struggling the most from the economic fallout LEISURE AND HOSPITALITY EMPLOYMENT LEADS GAINS, ADDING 1.2 MILLION JOBS In April, the industry lost 7.5 million jobs. Twenty-four percent of workers in the leisure and hospitality industry are Latino. INDICATORS National Latinos Employed • Working people over the age of 16, including 137.2 million 23.2 million those temporarily absent from their jobs Unemployed • Those who are available to work, trying to 21 million 5 million find a job, or expect to be called back from a layoff but are not working Civilian Labor Force 158.2 million 28.2 million • The sum of employed and unemployed people Unemployment Rate 13.3% 17.6 % • Share of the labor force that is unemployed Labor Force Participation Rate • Share of the population over the age of 16 60.8% 64.1% that is in the labor force Employment-Population Ratio • Share of the population over the age of 16 52.8% 52.8% that is working Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment Status of the Hispanic or Latino Population by Sex and Age,” Current Population Survey, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf (accessed June 5, 2020), Table A and A-3. www.unidosus.org PAGE 1 LATINO JOBS REPORT Employment of Latinos in May 2020 The U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) reported that employers added 2.5 million jobs in May, compared to 20.5 million jobs lost in April. -

Puerto Ricans at the Dawn of the New Millennium

puerto Ricans at the Dawn of New Millennium The Stories I Read to the Children Selected, Edited and Biographical Introduction by Lisa Sánchez González The Stories I Read to the Children documents, for the very first time, Pura Belpré’s contributions to North Puerto Ricans at American, Caribbean, and Latin American literary and library history. Thoroughly researched but clearly written, this study is scholarship that is also accessible to general readers, students, and teachers. Pura Belpré (1899-1982) is one of the most important public intellectuals in the history of the Puerto Rican diaspora. A children’s librarian, author, folklorist, translator, storyteller, and puppeteer who began her career the Dawn of the during the Harlem Renaissance and the formative decades of The New York Public Library, Belpré is also the earliest known Afro-Caribeña contributor to American literature. Soy Gilberto Gerena Valentín: New Millennium memorias de un puertorriqueño en Nueva York Edición de Carlos Rodríguez Fraticelli Gilberto Gerena Valentín es uno de los personajes claves en el desarrollo de la comunidad puertorriqueña Edwin Meléndez and Carlos Vargas-Ramos, Editors en Nueva York. Gerena Valentín participó activamente en la fundación y desarrollo de las principales organizaciones puertorriqueñas de la postguerra, incluyendo el Congreso de Pueblos, el Desfile Puertorriqueño, la Asociación Nacional Puertorriqueña de Derechos Civiles, la Fiesta Folclórica Puertorriqueña y el Proyecto Puertorriqueño de Desarrollo Comunitario. Durante este periodo también fue líder sindical y comunitario, Comisionado de Derechos Humanos y concejal de la Ciudad de Nueva York. En sus memorias, Gilberto Gerena Valentín nos lleva al centro de las continuas luchas sindicales, políticas, sociales y culturales que los puertorriqueños fraguaron en Nueva York durante el periodo de a Gran Migracíón hasta los años setenta. -

Los Veteranos—Latinos in WWII

Los Veteranos—Latinos in WWII Over 500,000 Latinos (including 350,000 Mexican Americans and 53,000 Puerto Ricans) served in WWII. Exact numbers are difficult because, with the exception of the 65th Infantry Regiment from Puerto Rico, Latinos were not segregated into separate units, as African Americans were. When war was declared on December 8, 1941, thousands of Latinos were among those that rushed to enlist. Latinos served with distinction throughout Europe, in the Pacific Theater, North Africa, the Aleutians and the Mediterranean. Among other honors earned, thirteen Medals of Honor were awarded to Latinos for service during WWII. In the Pacific Theater, the 158th Regimental Combat Team, of which a large percentage was Latino and Native American, fought in New Guinea and the Philippines. They so impressed General MacArthur that he called them “the greatest fighting combat team ever deployed in battle.” Latino soldiers were of particular aid in the defense of the Philippines. Their fluency in Spanish was invaluable when serving with Spanish speaking Filipinos. These same soldiers were part of the infamous “Bataan Death March.” On Saipan, Marine PFC Guy Gabaldon, a Mexican-American from East Los Angeles who had learned Japanese in his ethnically diverse neighborhood, captured 1,500 Japanese soldiers, earning him the nickname, the “Pied Piper of Saipan.” In the European Theater, Latino soldiers from the 36th Infantry Division from Texas were among the first soldiers to land on Italian soil and suffered heavy casualties crossing the Rapido River at Cassino. The 88th Infantry Division (with draftees from Southwestern states) was ranked in the top 10 for combat effectiveness. -

Code-Switching and Translated/Untranslated Repetitions in Nuyorican Spanglish

E3S Web of Conferences 273, 12139 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202127312139 INTERAGROMASH 2021 Code-switching and translated/untranslated repetitions in Nuyorican Spanglish Marina Semenova* Don State Technical University, 344000, Rostov-on-Don, Russia Abstract. Nuyorican Spanglish is a variety of Spanglish used primarily by people of Puerto Rican origin living in New York. Like many other varieties of the hybrid Spanglish idiom, it is based on extensive code- switching. The objective of the article is to discuss the main features of code-switching as a strategy in Nuyrican Spanglish applying the methods of linguistic, componential, distribution and statistical analysis. The paper focuses on prosiac and poetic texts created in Nuyrican Spanglish between 1978 and 2020, including the novel Yo-Yo Boing! by Giannina Braschi and 142 selected Boricua poems, which allows us to make certain observations on the philosophy and identity of Nuyorican Spanglish speakers. As a result, two types of code-switching as a strategy are denoted: external and internal code-switching for both written and oral speech forms. Further, it is concluded that repetition, also falling into two categories (translated and untranslated), embodies the core values of Nuyorican Spanglish (freedom of choice and focus on the linguistic personality) and reflects the philosophical basis for code-switching. 1 Introduction Nuyorican Spanglish is a Spanglish dialect used in New York’s East Side primarily by people of Puerto Rican origin, many of who are first- or second-generation New Yorkers. This means that Spanglish they use is rather the most effective way to communicate between English and Spanish cultures which come into an extremely intense contact in this cosmopolitan city. -

PERSPECTIVAS Issues in Higher Education Policy and Practice

PERSPECTIVAS Issues in Higher Education Policy and Practice Spring 2016 A Policy Brief Series sponsored by the AAHHE, ETS & UTSA Issue No. 5 Mexican Americans’ Educational Barriers and Progress: Is the Magic Key Within Reach? progress and engage intersectional also proffer strategies of resistance Executive Summary analytic frameworks. We explore that Mexican Americans employ to This policy brief is based on the how historical events and consequent overcome pernicious stereotypes and edited book The Magic Key: The practices and policies depleted the prejudicial barriers to educational Educational Journey of Mexican accumulation of human capital and achievement. Reaffirming how little Americans from K–12 to College contributed to disinvestments in has changed, we engage in a process and Beyond (Zambrana & Hurtado, Mexican American communities. of recovering dynamic history to 2015a), which focuses on the This scholarship decenters cultural inform Mexican American scholarship experiences of Mexican Americans problem-oriented and ethnic- and future policy and practice. in education. As the largest of the focused deficit arguments and Latino subgroups with the longest provides substantial evidence of history in America, and the lowest structural, institutional and normative AUTHORS levels of educational attainment, racial processes of inequality. New Ruth Enid Zambrana, Ph.D. this community warrants particular findings are introduced that create University of Maryland, College Park attention. Drawing from an more dynamic views of — and Sylvia Hurtado, Ph.D. interdisciplinary corpus of work, the new thinking about — Mexican University of California, Los Angeles authors move beyond the rhetoric of American educational trajectories. We Eugene E. García, Ph.D. Loui Olivas, Ed.D. José A. -

Introduction

Introduction Frederick Luis Aldama Scholar, playwright, spoken-word performer, award-winning poet, and avant-garde fiction author, since the 1980s Giannina Braschi has been creating up a storm in and around a panoply of Latinx hemispheric spaces. Her creative corpus reaches across different genres, regions, and historical epochs. Her critical works cover a wide range of subjects and authors, including Miguel de Cervantes, Garcilaso de la Vega, Juan Ramón Jiménez, Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer, Antonio Machado, César Vallejo, and García Lorca. Her dramatic poetry titles in Spanish include Asalto al tiempo (1981) and La comedia profana (1985). Her radically ex- perimental genre-bending titles include El imperio de los sueños (1988), the bilingual Yo-Yo Boing! (1998), and the English-penned United States of Banana (2011). With national and international awards and works ap- pearing in Swedish, Slovenian, Russian, and Italian, she is recognized as one of today’s foremost experimental Latinx authors. Her vibrant bilingually shaped creative expressions and innovation spring from her Latinidad, her Puerto Rican-ness that weaves in and through a planetary aesthetic sensibility. We discover as much in her work about US/Puerto Rico sociopolitical histories as we encounter the metaphysical and existential explorations of a Cervantes, Rabelais, Did- erot, Artaud, Joyce, Beckett, Stein, Borges, Cortázar, and Rosario Castel- lanos, for instance. With every flourish of her pen Braschi reminds us that in the distillation and reconstruction of the building blocks of the uni- verse there are no limits to what fiction can do. And, here too, the black scratches that form words and carefully composed blank spaces shape an absent world; her strict selection out of words and syntax is as important as the precise insertion of words and syntax to put us into the shoes of the “complicit reader” (Julio Cortázar’s term) to most productively interface, invest, and fill in the gaps of her storyworlds. -

College of Arts and Sciences

60 Study Abroad All students planning international study are strongly ate courses both here at Fairfield University and your encouraged to plan ahead to maximize program oppor- destination . Be sure to attend the Study Abroad Fair tunities and to ensure optimal match of major, minor, in September and attend a Study Abroad 101 session . previous language studies and intended destination . For Sophomores: attend a Study Abroad 101 meeting Study abroad is intended to build upon and enhance to get information about the application process and majors and minors and for this reason, program the steps required before your departure . Learn about choices will be carefully reviewed to ensure fit between your options and discuss them with your academic academics and destination . advisor, faculty, and family . For fall/spring programs in your Junior year: the deadline in February 1 . For Credits for studying abroad will only be granted for Juniors: you may study abroad during the fall of your academic work successfully completed in approved senior year at Fairfield programs for which grades international programs . All coursework must receive as well as credits are recorded . Applications are due pre-approval (coordinated through the International February 1 of Junior year to go abroad Fall of Senior Programs Office) . Only pre-approved courses, taken at year . To learn more about all our semester, summer, an approved program location, will be transcripted and spring break and intersession programs, consult with a accepted into a student’s curriculum . study abroad advisor or visit the study abroad website Fairfield University administers its own programs in for the current offerings . -

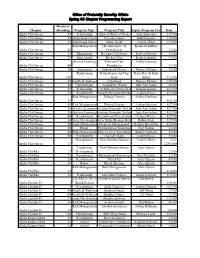

S08 Chapter Programming Report

Office of Fraternity Sorority Affairs Spring 08 Chapter Programming Report Members Chapter Attending Program Type Program Title Chapter Program Cord. Date Alpha Chi Omega 45 Scholarship How to Write a Check Judy Sukovich 1/27/08 Alpha Chi Omega 25 Sisterhood Event Pancake Dinner Juaki Kapadia 1/28/08 Alpha Chi Omega 35 Sisterhood Mixer Game Night Jennifer Ross 2/15/08 Risk Management The Importance of Kathleen Mullen Alpha Chi Omega 45 Checking In 3/2/08 Alpha Chi Omega 33 Educational By Law Cliff Notes Kaitlyn Herthel 3/3/08 Alpha Chi Omega 33 Educational By-Law Day Kaitlyn Herthel 3/3/08 Service Learning Embrace Kids Ashley Garrison Alpha Chi Omega 40 Foundation 3/9/08 Alpha Chi Omega 20 Sisterhood Sisterhood Dinner Monica Milano 3/9/08 Fundraising Philanthropy and Flap Katie Karr & Judy Alpha Chi Omega 188 Jacks Adam 3/12/08 Alpha Chi Omega 38 Health & Wellness Sisterhood Monica Milano 3/29/08 Alpha Chi Omega 84 Philanthropy Around the World Judy Ann Adam 4/2/08 Alpha Chi Omega 55 ScholarshipHow to Write the Perfect E-MailJennifer Kantor 4/13/08 Alpha Chi Omega 25 Recruitment Sorority Recruitment Fair Lauren Ricca 4/15/08 Risk Management Taking Chances Ashley Garrison Alpha Chi Omega 27 4/21/08 Alpha Chi Omega 43 Risk Management Hazing Policies Ashley Garrison 4/27/08 Alpha Chi Omega 36 Service LearningPreventing Domestic Violence Judy Ann Adam 4/27/08 Alpha Chi Omega 36 Service LearningPreventing Domestic Violence Judy Ann Adam 4/27/08 Alpha Chi Omega 40 Recruitment Recruitment Presentation Lauren Ricca 4/27/08 Alpha Chi Omega 30Career -

Hispanic/Latino American Older Adults

Ethno MEd Health and Health Care of Hispanic/Latino American Older Adults http://geriatrics.stanford.edu/ethnomed/latino Course Director and Editor in Chief: VJ Periyakoil, Md Stanford University School of Medicine [email protected] 650-493-5000 x66209 http://geriatrics.stanford.edu Authors: Melissa talamantes, MS University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio Sandra Sanchez-Reilly, Md, AGSF GRECC South Texas Veterans Health Care System; University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio eCampus Geriatrics IN THE DIVISION OF GENERAL INTERNAL MEDICINE http://geriatrics.stanford.edu © 2010 eCampus Geriatrics eCampus Geriatrics hispanic/latino american older adults | pg 2 CONTENTS Description 3 Culturally Appropriate Geriatric Care: Learning Resources: Learning Objectives 4 Fund of Knowledge 28 Instructional Strategies 49 Topics— Topics— Introduction & Overview 5 Historical Background, Assignments 49 Topics— Mexican American 28 Case Studies— Terminology, Puerto Rican, Communication U.S. Census Definitions 5 Cuban American, & Language, Geographic Distribution 6 Cultural Traditions, Case of Mr. M 50 Population Size and Trends 7 Beliefs & Values 29 Depression, Gender, Marital Status & Acculturation 31 Case of Mrs. R 51 Living Arrangements 11 Culturally Appropriate Geriatric Care: Espiritismo, Language, Literacy Case of Mrs. J 52 & Education 13 Assessment 32 Topics— Ethical Issues, Employment, End-of-Life Communication 33 Case of Mr. B 53 Income & Retirement 16 Background Information, Hospice, Eliciting Patients’ Perception -

LATINO and LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES SPACE for ENRICHMENT and RESEARCH Laser.Osu.Edu

LATINO AND LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES SPACE FOR ENRICHMENT AND RESEARCH laser.osu.edu AT A GLANCE The Ohio State University Latino and Latin American Space for Enrichment and Research (LASER) is a forum Latino Studies: for Ohio State faculty, undergraduate and graduate Minor Program—Lives in students, and faculty and visiting scholars from around the Spanish and Portuguese the world, to learn from one another about Latino and department; the Latino Studies curriculum has an “Americas” Latin American history, culture, economics, literature, (North, Central, and South geography, and other areas. America) focus. Graduate Scholar in Residence Program: Fosters an intellectual community among Chicano/Latino and Latin Americanist graduate students by creating mentoring opportunities between graduate and undergraduate students. Faculty: Drawn from 1000-2000 scholars doing work in Latino-American William Oxley Thompson studies LASER MENTOR PROGRAM LASER Mentors serve as role models as well as bridge builders between Latinos in high school and Ohio State as well as between undergraduates at Ohio State and graduate and professional school. The goal: to expand the presence of Latinos in higher education as well as to enrich the Ohio State undergraduate research experience and to prepare students for successful transition to advanced professional and graduate school programs. Research and exchange of Latino and Latin American studies. GOALS OF LASER OUR MISSION IS TO PROMOTE 1: ENHANCING RESEARCH, SERVICE, PEDAGOGY STATE-OF-THE-ART RESEARCH AND EXCHANGE IN THE FIELD OF LATINO LASER participants seek to pool their knowledge and interests to create new directions for Latino and Latin AND LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES. American research, teaching, and service. -

Allá Y Acá: Locating Puerto Ricans in the Diaspora(S)

Diálogo Volume 5 Number 1 Article 4 2001 Allá y Acá: Locating Puerto Ricans in the Diaspora(s) Miriam Jiménez Román Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/dialogo Part of the Latin American Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Jiménez Román, Miriam (2001) "Allá y Acá: Locating Puerto Ricans in the Diaspora(s)," Diálogo: Vol. 5 : No. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/dialogo/vol5/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Latino Research at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Diálogo by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Allá y Acá: Locating Puerto Ricans in the Diaspora(s) Cover Page Footnote This article is from an earlier iteration of Diálogo which had the subtitle "A Bilingual Journal." The publication is now titled "Diálogo: An Interdisciplinary Studies Journal." This article is available in Diálogo: https://via.library.depaul.edu/dialogo/vol5/iss1/4 IN THE DIASPORA(S) Acá:AlláLocatingPuertoRicansy ©Miriam ©Miriam Jiménez Román Yo soy Nuyorican.1 Puerto Rico there was rarely a reference Rico, I was assured that "aquí eso no es Así es—vengo de allá. to los de afuera that wasn't, on some un problema" and counseled as to the Soy producto de la migración level, derogatory, so that even danger of imposing "las cosas de allá, puertorriqueña, miembro de la otra compliments ("Hay, pero tu no pareces acá." Little wonder, then, that twenty- mitad de la nación.