Blue Ocean Leadership Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Extra-Ordinary Civil Writ Jurisdiction) in the Matter of a Public Interest Litigation W.P

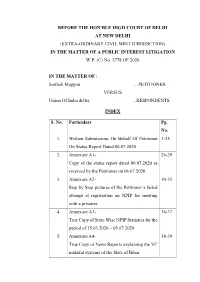

BEFORE THE HON’BLE HIGH COURT OF DELHI AT NEW DELHI (EXTRA-ORDINARY CIVIL WRIT JURISDICTION) IN THE MATTER OF A PUBLIC INTEREST LITIGATION W.P. (C) No. 3778 OF 2020 IN THE MATTER OF : Sarthak Maggon …PETITIONER VERSUS Union Of India &Ors. ...RESPONDENTS INDEX S. No. Particulars Pg. No. 1. Written Submissions On Behalf Of Petitioner 1-25 On Status Report Dated 06.07.2020 2. Annexure A1- 26-29 Copy of the status report dated 06.07.2020 as received by the Petitioner on 06.07.2020 3. Annexure A2- 30-35 Step by Step pictures of the Petitioner’s failed attempt at registration on NPIP for meeting with a prisoner. 4. Annexure A3- 36-37 True Copy of State-Wise NPIP Statistics for the period of 15.03.2020 – 05.07.2020 5. Annexure A4- 38-39 True Copy of News Reports explaining the VC mulakat systems of the State of Bihar 6. Annexure A5- 40-42 True Copy of News Reports explaining the VC mulakat systems of the State of Gujarat 7. Annexure A6- 43-44 True Copy of News Report explaining the Whatsapp Video Call mulakat system by the Prison Department of the State of Tamil Nadu 8. Annexure A7- 45-49 True Copy of Visitation Guidelines by Pennsylvania Department of Corrections in the United States of America. 9. Annexure A8- 50-52 True Copy of Order of this Hon’ble Court in W.P. (CRL.) 855/2020 dated 09.06.2020 10. Annexure A9- 53-57 True Copy of Order of this Hon’ble Court in W.P. -

Global War on Terrorism and Prosecution of Terror Suspects: Select Cases and Implications for International Law, Politics, and Security

GLOBAL WAR ON TERRORISM AND PROSECUTION OF TERROR SUSPECTS: SELECT CASES AND IMPLICATIONS FOR INTERNATIONAL LAW, POLITICS, AND SECURITY Srini Sitaraman Introduction The global war on terrorism has opened up new frontiers of transnational legal challenge for international criminal law and counterterrorism strategies. How do we convict terrorists who transcend multiple national boundaries for committing and plotting mass atrocities; what are the hurdles in extraditing terrorism suspects; what are the consequences of holding detainees in black sites or secret prisons; what interrogation techniques are legal and appropriate when questioning terror suspects? This article seeks to examine some of these questions by focusing on the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT), particularly in the context of counterterrorism strategies that the United States have pursued towards Afghanistan-Pakistan (Af-Pak) since the September 2001 terror attacks on New York and Washington D.C. The focus of this article is on the methods employed to confront terror suspects and terror facilitators and not on the politics of cooperation between the United States and Pakistan on the Global War on Terrorism or on the larger military operation being conducted in Afghanistan and in the border regions of Pakistan. This article is not positioned to offer definitive answers or comprehensive analyses of all pertinent issues associated with counterterrorism strategies and its effectiveness, which would be beyond the scope of this effort. The objective is to raise questions about the policies that the United States have adopted in conducting the war on terrorism and study its implications for international law and security. It is to examine whether the overzealousness in the execution of this war on terror has generated some unintended consequences for international law and complicated the global judicial architecture in ways that are not conducive to the democratic propagation of human rights. -

Thr Ugh Time

IN RETROSPECT A JOURNEY THR UGH TIME From a civil nuclear pact with the US to the ‘Missile Man’ becoming the President; from Vodafone India 14 buying Hutchison’s India assets to the July govt bringing legislation to ‘retro tax’ 6 END OF AN ERA Mukesh and Anil Ambani 2001 carry the body of their father and Reliance the mega deal; from the country’s best SIGNALLING A THAW founder Dhirubhai Ambani. The brothers Prime Minister July split the group in 2005, three years after the annual economic growth figures to Atal Bihari Vajpayee with 2002 senior Ambani’s death. PHOTO: REUTERS Pakistan President its worst market crash; from Pervez Musharraf during the Agra Summit, the sending satellites to the moon first meeting of the leaders after the and Mars to getting ravaged by Kargil war of 1999. terror and natural calamities; PHOTO: PTI from citizens spilling on to the roads for safeguard of their rights to enactment of landmark laws like RTI, RTE and NREGA — India has seen it all in the first 15 years of this PEOPLE’S PRESIDENT century. Business Standard ‘Missile Man of India’ looks at the most important 25 A P J Abdul Kalam (right) waits to be sworn in as the events since the year 2001 11th President of India. Sitting July next to him is his predecessor 2002 K R Narayanan. BS PHOTO THE UPA DECADE KICKS IN President A $12-BN PROJECT Posco President BLOCKBUSTER JOB SCHEME The National Rural A P J Abdul Kalam hands over to Manmohan Chang O Kang with Odisha Chief Minister Naveen Employment Guarantee Act is implemented, in 200 18 Singh a letter appointing him the new Prime 15 Patnaik in New Delhi. -

Afzal Guru's Case

Afzal Guru's Case The UPA government does not appear to have any interest in implementing the death sentence given to Mohammad Afzal Guru, the main accused involved in the conspiracy behind the attack on the Parliament House on 13th. December, 2001. Afzal has been marking his time in Tihar jail since September, 2005, when the petitions seeking review of the judgement upholding the death sentence on Afzal Guru were dismissed by the Supreme Court. On Dec 13, 2001, five gunmen who tried to storm the heavily guarded parliament complex were shot dead by the security personnel. Seven members of the security force were also killed in the said encounter. The attack on the Parliament House was jointly conducted by the Laskhar-e-Toiba (LeT) and Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM), two Kashmiri militant groups operating from Pakistan. Just before the scheduled execution of Afzal Guru on October 20, 2006, Afzal’s family had filed a clemency plea with the President who referred it to home ministry which in turn sent it to the Delhi government for its views, as per the procedure. Since then the matter is pending, with the Union government showing no urgency or interest in expediting the matter. The death sentence awarded to Afzal Guru had triggered wide-spread protests in Kashmir. J&K politicians like Omar Abdullah of National Conference, Ghulam Nabi Azad of the Congress and Mehbooba Mufti of the People's Democratic Party had pleaded against hanging Afzal Guru..Former Union Home Minister Shivraj Patil had said on one occasion that hanging Afzal would prejudice India’s attempt to bring back Sarabjit Singh, an Indian on the death row in Pakistan. -

Jihadist Violence: the Indian Threat

JIHADIST VIOLENCE: THE INDIAN THREAT By Stephen Tankel Jihadist Violence: The Indian Threat 1 Available from : Asia Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 www.wilsoncenter.org/program/asia-program ISBN: 978-1-938027-34-5 THE WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS, established by Congress in 1968 and headquartered in Washington, D.C., is a living national memorial to President Wilson. The Center’s mission is to commemorate the ideals and concerns of Woodrow Wilson by providing a link between the worlds of ideas and policy, while fostering research, study, discussion, and collaboration among a broad spectrum of individuals concerned with policy and scholarship in national and interna- tional affairs. Supported by public and private funds, the Center is a nonpartisan insti- tution engaged in the study of national and world affairs. It establishes and maintains a neutral forum for free, open, and informed dialogue. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. The Center is the publisher of The Wilson Quarterly and home of Woodrow Wilson Center Press, dialogue radio and television. For more information about the Center’s activities and publications, please visit us on the web at www.wilsoncenter.org. BOARD OF TRUSTEES Thomas R. Nides, Chairman of the Board Sander R. Gerber, Vice Chairman Jane Harman, Director, President and CEO Public members: James H. -

International, English Language Phd Program in Gender Studies Thesis

avtoris stili daculia Title of PhD Program: International, English language PhD program in Gender Studies Thesis title: Deciphering Dissent and Resistance: Student Activism and Gender in Georgia and India Name of Student: Maia Barkaia Name, degree and positions of Academic Supervisor(s): Parvis Ghassem-Fachandi, PhD, Assistant Professor, SAS, Rutgers Date: 01.09.2014 Institution: Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University Faculty of Social and Political Sciences PhD program in Gender Studies is administered by the Center for Social Sciences at TSU. Table of Contents Abstract..................................................................................................................................5 Acknowledgment …………………………………………………………………………..6 List of Figures………………………………………………………………………………7 List of Abbreviations and Acronyms ……………………………………………………..8 Chapter One: Introduction………………………………………………………………..9 An Outline of the Ph.D. Thesis………………………………………………………14 Chapter Two: Theoretical Framework and Literature Review………………………..16 Chapter Three: Methodology…………………………………………………………….32 Chapter Four: Inception – Student Organizations……………………………………..41 Introduction………………………………………………………………………...41 Introduction to Student Activism at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), Delhi, India………………………………………………………………………………..42 All India Students’ Association (AISA)…………………………………...47 Indian Students’ Association – Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP)………………………………………………………….56 Student Activism in Tbilisi, Georgia………………………………………………60 Laboratory 1918…………………………………………………………..60 -

Women in Indira Gandhi's India, 1975-1977

This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights and duplication or sale of all or part is not permitted, except that material may be duplicated by you for research, private study, criticism/review or educational purposes. Electronic or print copies are for your own personal, non- commercial use and shall not be passed to any other individual. No quotation may be published without proper acknowledgement. For any other use, or to quote extensively from the work, permission must be obtained from the copyright holder/s. Emerging from the Emergency: women in Indira Gandhi’s India, 1975-1977 Gemma Scott Doctor of Philosophy in History March 2018 Keele University Abstract India’s State of Emergency (1975-1977) is a critical period in the independent nation’s history. The government’s suspension of democratic norms and its institution of many, now infamous repressive measures have been the subject of much commentary. However, scholars have not examined Emergency politics from a gendered perspective. Women’s participation in support for and resistance to the regime and their experiences of its programmes are notably absent from historiography. This thesis addresses this gap and argues that a gendered perspective enhances our understanding of this critical period in India’s political history. It assesses the importance of gendered narratives and women to the regime’s dominant political discourses. I also analyse women’s experiences of Emergency measures, particularly the regime’s coercive sterilisation programme and use of preventive detention to repress dissent. I explore how gendered power relations and women’s status affected the implementation of these measures and people’s attempts to negotiate and resist them. -

'Prison Reforms' Held at India Habitat Centre, New Delhi

MINUTES & RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE NATIONAL SEMINAR ON ‘PRISON REFORMS’ HELD AT INDIA HABITAT CENTRE, NEW DELHI ON 15TH APRIL, 2011 The National Human Rights Commission organized a National Seminar on Prison Reforms on 15th April, 2011 at Jacaranda Hall, IHC, New Delhi. The meeting was attended by Justice KG Balakrishnan, Hon’ble Chairperson, NHRC, Justice GP Mathur Hon’ble Member NHRC, Justice BC Patel Hon’ble Member NHRC, Satyabrata Pal Member, NHRC, Shri Sunil Krishna Director General(Investigation), Shri JP Meena JS, NHRC, representatives of State and Central Govt, members of civil society and other professionals. The list of participants is enclosed. Welcoming the participants, Director General (Investigation), NHRC, Sri Sunil Krishna, said that the prison reform has always been a matter of serious concern for the Commission. He stated that the prisons should offer conditions that are compatible with human dignity and conducive to social mainstreaming and that a person in custody in a civilized society should be treated like any other human being outside the prison. He said that the main issues for deliberations in the national seminar were prisoners’ rights, need for transparency and accountability, monitoring of prison conditions, modernization of prison administration and sensitization and expansion of prison staff. Overcrowding in prisons is one of the reasons for the unhygienic conditions prevailing in prisons. When the Supreme Court in a memorable judgement on the case commonly referred to as the Common Cause case, gave detailed directions regarding the release of undertrials on bail, NHRC in 1999 addressed all the State IGs of Prisons to take measures in consultation with their High Courts and State Legal Aid Authorities. -

Re-Inhuman Conditions in 1382 V. State of Assam, 2018

Re-Inhuman Conditions In 1382 ... vs State Of Assam on 25 September, 2018 Supreme Court of India Re-Inhuman Conditions In 1382 ... vs State Of Assam on 25 September, 2018 Author: M B Lokur REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 406 OF 2013 RE- INHUMAN CONDITIONS IN 1382 PRISONS ORDER Madan B. Lokur, J. 1. Over the years, public interest litigation has brought immense social change through interventions made and directions issued by this Court. Public interest litigation has been initiated, very rarely, by suo motu1 exercise of jurisdiction by this Court. On most occasions, it has been initiated through a writ petition filed by activist individuals or organisations2. Again, quite infrequently, it has been initiated on the basis of a communication received by this Court3. Suo Motu Writ Petitions: In Re: Outrage As Parents End Life After Childs Dengue Death, (2016) 10 SCC 709, In Re: Death of 25 Chained Inmates in Asylum Fire in Tamil Nadu v. Union of India, (2002) 3 SCC 31, In Re: Indian Woman says gang-raped on orders of Village Court published in Business and Financial News, (2014) 2 Signature Not Verified SCC 786 Digitally signed by Writ Petitions filed: SANJAY KUMAR Date: 2018.09.25 17:26:35 IST MC Mehta v. Union of India [Oleum Gas Leak], (1986) 2 SCC 176, Pt. Parmanand Katara v. Union of Reason: India, (1989) 4 SCC 286, Bachpan Bachao Andolan v. Union of India, (2011) 5 SCC 1 Letters Petitions: Prem Shankar Shukla v. Delhi Administration, (1980) 3 SCC 526, Sheela Barse v. -

Details of Correctional Service Medals Awarded to the Prison Personnel Since Th Year 2000

DETAILS OF CORRECTIONAL SERVICE MEDALS AWARDED TO THE PRISON PERSONNEL SINCE TH YEAR 2000 REPUBLIC DAY 2000 PRESIDENT CORRECTIONAL SERVICE MEDAL FOR DISTINGUISHED SERVICE: 1. Shri Prakash Chiman Rao Yadav, Physical Training Instructor, Jail Officers Training College, PUNE. PRESIDENT CORRECTIONAL SERVICE MEDAL FOR GALLANTRY: 1. Shri Sobha Lal Nishad, Warder, Central Prison, Naini, Allahabad, U.P. 2. Shri Rama Kant Tiwari, Superintendent of Jail, District Prison, Lucknow, U.P. 3. Shri Ashok Kumar Gautam, Jailor,District Prison, Lucknow,U.P. CORRECTIONAL SERVICE MEDAL FOR GALLANTRY 1. Shri Ashok Kumar Gautam, Jailor, District Prison, Lucknow, U.P. PRESIDENT CORRECTIONAL SERVICE MEDAL FOR MERITORIOUS SERVICE: 1. Shri Bankim Chandra Mohanty, Senior Superintendent, Circle Jail Class-I, Behrampur, Orissa. 2. Ch.Dinesh Kumar, Chief Superintendent of Jails, PONDICHERRY. 3. Shri Yadeo Sadashiv Bhor, Chemical Superintendent, Central Prison, Nasik Road, Maharashtra. 4. Shri Rambhau Sheshrao Thorat, Sepoy, Central Prison, Parbhani, Maharashtra 5. Shri Shripatrao Purshotta Bihade, Weaving Supervisor,Central Prison Nagpur,Maharashtra. 6. Shri Raghunath Baburao Panke, Havildar, Central Prison, Yeravada, Maharashtra. 7. Shri Dhyandeo Abhiman Karche, Subhedar, Central Prison Nagpur, Maharashtra. 8. Shri Rajendra Singh, Jailor, District Prison Jalore, Rajasthan. 9. Shri G.Ramachandran, Superintendent of Prisons, Central Prison Chennai, Tamilnadu. 10. Shri Hari Shanker Singh, Deputy Inspector General (Prisons), Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh. 11. Shri Rekh Bahadur Thapa, Head Warder, Central Jail No.4, Tihar,Delhi. 12. Shri Balappa Shivarudrappa Abbai, Superintendent, Central Prison, Bangalore, Karnataka 13. Shri Kuber Singh Tomar, Deputy Jailor, Central Jail Indore,M.P. 14. Shri Ranjit Singh Bhati, Assistant Jailor, Central Jail, Indore, M.P. 15. Shri Kamal Kishore Kagoria, Assistant Jailor,Central Prison, Bilaspur, M.P. -

Jailed in Baroda Dynamite Case, a Socialist Leader Looks Back on the Emergency

Jailed in Baroda Dynamite Case, a Socialist Leader Looks Back on the Emergency Sidharth Bhatia (From The Wire) Even if Narendra Modi wanted to impose another Emergency, he says, it will not be easy. The media and the judiciary have learnt their lesson from that time and will not give in so easily Mumbai: On the morning of June 26, 1975, Dr G.G. Parikh set out as always to go to his clinic—and never came back. His wife and daughter were not worried. At the stroke of midnight, an internal Emergency had been declared and Parikh had made arrangements to disappear. “ I had known that Indira Gandhi would do something drastic—the railway strike of 1974, the JP movement, the student riots and then the Allahabad court judgment unseating her—she was under a lot of pressure and would react,” he says. And she did, by clamping down on fundamental rights, freedom of speech and political activities. Politicians, intellectuals and activists were being picked up and Parikh, a life-long socialist was sure that he would be too. “Socialists had some experience of going underground in 1942. I simply followed the same methods,” he recalls. Now 91, the spry doctor still has a busy time running his medical practice, managing an NGO on the outskirts of Mumbai and helping bring out Janata, the weekly magazine of the Praja Socialist Party, which has been in existence since 1946. Page 1 of 3 After staying with friends for a few days, Parikh moved to Gujarat, where a non- Congress government led by Babubhai Patel was in office and the situation was not so drastic as elsewhere. -

State/UT-Wise Number of Jails, Their Location and Capacity As on 30.11.2012

Annexure State/UT-wise number of jails, their location and capacity as on 30.11.2012 Actual Capacity . Total No Sanc- Sl. l. Name of Jail Location tioned - No. capa- Jail Jail S Jail Jail Status city No. of Convicts No. of Under trials Others Total ANDHRA PRADESH - CENTRAL JAILS 1. Central Prison 1 Hyderabad 650 69 648 0 717 2. Central Prison 2 Cherlapalli 1790 939 894 6 1839 3. Central Prison 3 Warangal 1203 588 222 0 810 4. Central Prison 4 Rajahmundry 1648 925 395 16 1336 5. Central Prison 5 Visakhapatnam 770 407 494 0 901 6. Central Prison 6 Kadapa 1000 709 190 9 908 7. Central Prison 7 Nellore 500 302 145 0 447 ANDHRA PRADESH – DISTRICT JAILS 8. District Jail 1 Sangareddy 260 26 156 0 182 9. District Jail 2 Nalgonda 160 16 118 0 134 10. District Jail 3 Mahaboobnagar 147 14 275 0 289 11. District Jail 4 Nizamabad 460 29 183 0 212 12. District Jail 5 Karimnagar 349 24 251 0 275 13. District Jail 6 Adilabad 331 31 126 0 157 14. District Jail 7 Vijayawada 166 13 280 0 293 15. District Jail 8 Guntur 255 42 162 0 204 16. District Jail 9 Ananthapur 270 13 124 0 137 17. District Jail 10 Ongole 210 18 157 0 175 18. District Jail 11 Srikakulam 176 10 46 0 56 19. District Jail 12 Khammam 340 26 193 0 219 20. District Jail 13 Chittor 150 26 145 0 171 ANDHRA PRADESH – SUB JAILS 21. Sub Jail 1 Pargi 57 0 65 0 65 22.