Morphology of the Gastrointestinal Tract in Primates : Comparisons with Other Mammals in Relation to Diet David J Chivers, Claude Marcel Hladik

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Skin As a Mirror of the Gastrointestinal Tract

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22516/25007440.397 Case report The skin as a mirror of the gastrointestinal tract Martín Alonso Gómez,1* Adán Lúquez,2 Lina María Olmos.3 1 Associate Professor of Gastroenterology in the Abstract Gastroenterology and Endoscopy Unit of the National University Hospital and the National University of We present four cases of digestive bleeding whose skin manifestations guided diagnosis prior to endoscopy. Colombia in Bogotá Colombia These cases demonstrate the importance of a good physical examination of all patients rather than just 2 Internist and Gastroenterologist at the National focusing on laboratory tests. University of Colombia in Bogotá, Colombia 3 Dermatologist at the Military University of Colombia and the Dispensario Medico Gilberto Echeverry Keywords Mejia in Bogotá, Colombia Skin, bleeding, endoscopy, pemphigus. *Correspondence: [email protected]. ......................................... Received: 30/01/18 Accepted: 13/04/18 Despite great technological advances in diagnosis of disea- CASE 1: VULGAR PEMPHIGUS ses, physical examination, particularly an appropriate skin examination, continues to play a leading role in the detec- This 46-year-old female patient suffered an episode of hema- tion of gastrointestinal pathologies. The skin, the largest temesis with expulsion of whitish membranes through her organ of the human body, has an area of 2 m2 and a thick- mouth during hospitalization. Upon physical examination, ness that varies between 0.5 mm (on the eyelids) to 4 mm she was found to have multiple erosions and scaly plaques (on the heel). It weighs approximately 5 kg. (1) Many skin with vesicles that covered the entire body surface. After a manifestations may indicate systemic diseases. -

6 Physiology of the Colon : Motility

#6 Physiology of the colon : motility Objectives : ● Parts of the Colon ● Functions of the Colon ● The physiology of Different Colon Regions ● Secretion in the Colon ● Nutrient Digestion in the Colon ● Absorption in the Colon ● Bacterial Action in the Colon ● Motility in the Colon ● Defecation Reflex Doctors’ notes Extra Important Resources: 435 Boys’ & Girls’ slides | Guyton and Hall 12th & 13th edition Editing file [email protected] 1 ﺗﻛرار ﻣن اﻟﮭﺳﺗوﻟوﺟﻲ واﻷﻧﺎﺗوﻣﻲ The large intestine ● This is the final digestive structure. ● It does not contain villi. ● By the time the digested food (chyme) reaches the large intestine, most of the nutrients have been absorbed. ● The primary role of the large intestine is to convert chyme into feces for excretion. Parts of the colon ● The colon has a length of about 150 cm. ( 1.5 meters) (one-fifth of the whole length of GIT). ● It consists of the ascending & descending colon, transverse colon, sigmoid colon, rectum and anal canal. 3 ● The transit of radiolabeled chyme through 4 the large intestine occurs in 36-48 hrs. 2 They know this how? By inserting radioactive chyme. 1 6 5 ❖ Mucous membrane of the colon ● Lacks villi and has many crypts of lieberkuhn. ● They consists of simple short glands lined by mucous-secreting goblet cells. Main colonic secretion is mucous, as the colon lacks digestive enzymes. ● The outer longitudinal muscle layer is modified to form three longitudinal bands called taenia coli visible on the outer surface.(Taenia coli: Three thickened bands of muscles.) ● Since the muscle bands are shorter than the length of the colon, the colonic wall is sacculated and forms haustra.(Haustra: Sacculation of the colon between the taenia.) Guyton corner : mucus in the large intestine protects the intestinal wall against excoriation, but in addition, it provides an adherent medium for holding fecal matter together. -

Human Anatomy and Physiology

LECTURE NOTES For Nursing Students Human Anatomy and Physiology Nega Assefa Alemaya University Yosief Tsige Jimma University In collaboration with the Ethiopia Public Health Training Initiative, The Carter Center, the Ethiopia Ministry of Health, and the Ethiopia Ministry of Education 2003 Funded under USAID Cooperative Agreement No. 663-A-00-00-0358-00. Produced in collaboration with the Ethiopia Public Health Training Initiative, The Carter Center, the Ethiopia Ministry of Health, and the Ethiopia Ministry of Education. Important Guidelines for Printing and Photocopying Limited permission is granted free of charge to print or photocopy all pages of this publication for educational, not-for-profit use by health care workers, students or faculty. All copies must retain all author credits and copyright notices included in the original document. Under no circumstances is it permissible to sell or distribute on a commercial basis, or to claim authorship of, copies of material reproduced from this publication. ©2003 by Nega Assefa and Yosief Tsige All rights reserved. Except as expressly provided above, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission of the author or authors. This material is intended for educational use only by practicing health care workers or students and faculty in a health care field. Human Anatomy and Physiology Preface There is a shortage in Ethiopia of teaching / learning material in the area of anatomy and physicalogy for nurses. The Carter Center EPHTI appreciating the problem and promoted the development of this lecture note that could help both the teachers and students. -

Anatomy of the Digestive System

The Digestive System Anatomy of the Digestive System We need food for cellular utilization: organs of digestive system form essentially a long !nutrients as building blocks for synthesis continuous tube open at both ends !sugars, etc to break down for energy ! alimentary canal (gastrointestinal tract) most food that we eat cannot be directly used by the mouth!pharynx!esophagus!stomach! body small intestine!large intestine !too large and complex to be absorbed attached to this tube are assorted accessory organs and structures that aid in the digestive processes !chemical composition must be modified to be useable by cells salivary glands teeth digestive system functions to altered the chemical and liver physical composition of food so that it can be gall bladder absorbed and used by the body; ie pancreas mesenteries Functions of Digestive System: The GI tract (digestive system) is located mainly in 1. physical and chemical digestion abdominopelvic cavity 2. absorption surrounded by serous membrane = visceral peritoneum 3. collect & eliminate nonuseable components of food this serous membrane is continuous with parietal peritoneum and extends between digestive organs as mesenteries ! hold organs in place, prevent tangling Human Anatomy & Physiology: Digestive System; Ziser Lecture Notes, 2014.4 1 Human Anatomy & Physiology: Digestive System; Ziser Lecture Notes, 2014.4 2 is suspended from rear of soft palate The wall of the alimentary canal consists of 4 layers: blocks nasal passages when swallowing outer serosa: tongue visceral peritoneum, -

GLOSSARYGLOSSARY Medical Terms Common to Hepatology

GLOSSARYGLOSSARY Medical Terms Common to Hepatology Abdomen (AB-doh-men): The area between the chest and the hips. Contains the stomach, small intestine, large intestine, liver, gallbladder, pancreas and spleen. Absorption (ub-SORP-shun): The way nutrients from food move from the small intestine into the cells in the body. Acetaminophen (uh-seat-uh-MIN-oh-fin): An active ingredient in some over-the-counter fever reducers and pain relievers, including Tylenol. Acute (uh-CUTE): A disorder that has a sudden onset. Alagille Syndrome (al-uh-GEEL sin-drohm): A condition when the liver has less than the normal number of bile ducts. It is associated with other characteristics such as particular facies, abnormal pulmonary artery and abnormal vertebral bodies. Alanine Aminotransferase or ALT (AL-ah-neen uh-meen-oh-TRANZ-fur-ayz): An enzyme produced by hepatocytes, the major cell types in the liver. As cells are damaged, ALT leaks out into the bloodstream. ALT levels above normal may indicate liver damage. Albumin (al-BYEW-min): A protein that is synthesized by the liver and secreted into the blood. Low levels of albumin in the blood may indicate poor liver function. Alimentary Canal (al-uh-MEN-tree kuh-NAL): See Gastrointestinal (GI) Tract. Alkaline Phosphatase (AL-kuh-leen FOSS-fuh-tayz): Proteins or enzymes produced by the liver when bile ducts are blocked. Allergy (AL-ur-jee): A condition in which the body is not able to tolerate or has a reaction to certain foods, animals, plants, or other substances. Amino Acids (uh-MEE-noh ASS-udz): The basic building blocks of proteins. -

The Gastrointestinal System & Digestion Visual Worksheet

Biology 202: The Gastrointestinal System & Digestion 1) Label the components of the digestive system. Descending colon Anus Pancreas Mouth Pharynx Salivary glands Anal canal Transverse colon Ileum Jejunum Spleen Rectum Liver Submandibular gland Tongue Ascending colon Duodenum Appendix Large intestine Sigmoid colon Small intestine Cecum Gallbladder Stomach Esophagus Parotid gland Sublingual gland Source Lesson: Digestive System: Functions & Processes 2) Label the image below. Serosa Submucous plexus Muscularis externa Submucosa Myenteric plexus Muscular interna Source Lesson: Role of the Enteric Nervous System in Digestion 3) Label the structures of the alimentary canal. Some terms may be used more than once. Vein Mesentery Mucosa Submucosal plexus Epithelium Gland in mucosa Nerve Muscularis Serosa Lymphatic tissue Muscularis mucosae Glands in submucosa Lamina propria Submucosa Duct of gland outside tract Gland in mucosa Lumen Artery Longitudinal muscle Musculararis Areolar connective tissue Circular muscle Myenteric plexus Source Lesson: The Upper Alimentary Canal: Key Structures, Digestive Processes & Food Propulsion 4) Label the image below. Stomach Trachea Lower esophageal sphincter Esophagus Upper esophageal sphincter Source Lesson: The Upper Alimentary Canal: Key Structures, Digestive Processes & Food Propulsion 5) Label the anatomy of the oral cavity. Upper lip Tonsil Inferior labial frenulum Floor of mouth Tongue Superior labial frenulum Lower lip Teeth Retromolar trigone Palatine arch Hard palate Uvula Glossopalatine arch Soft palate Gingiva Source Lesson: The Oral Cavity: Structures & Functions 6) Label the structures of the oral cavity. Some terms may be used more than once. Hard palate Oropharynx Soft palate Pharyngeal tonsil Oral cavity Lingual tonsil Superior lip Teeth Palatine tonsil Tongue Inferior lip Source Lesson: The Oral Cavity: Structures & Functions 7) Label the image below. -

Sigmoid-Recto-Anal Region of the Human Gut

Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.29.6.762 on 1 June 1988. Downloaded from Gut, 1988, 29, 762-768 Intramural distribution of regulatory peptides in the sigmoid-recto-anal region of the human gut G-L FERRI, T E ADRIAN, JANET M ALLEN, L SOIMERO, ALESSANDRA CANCELLIERI, JANE C YEATS, MARION BLANK, JULIA M POLAK, AND S R BLOOM From the Department ofAnatomy, 'Tor Vergata' University, Rome, Italy and Departments ofMedicine and Histochemistry, RPMS, Hammersmith Hospital, London SUMMARY The distribution of regulatory peptides was studied in the separated mucosa, submucosa and muscularis externa taken at 10 sampling sites encompassing the whole human sigmoid colon (five sites), rectum (two sites), and anal canal (three sites). Consistently high concentrations of VIP were measured in the muscle layer at most sites (proximal sigmoid: 286 (16) pmol/g, upper rectum: 269 (17), a moderate decrease being found in the distal smooth sphincter (151 (30) pmol/g). Values are expressed as mean (SE). Conversely, substance P concentrations showed an obvious decline in the recto-anal muscle (mid sigmoid: 19 (2 0) pmol/g, distal rectum: 7 1 (1 3), upper anal canal: 1-6 (0 6)). Somatostatin was mainly present in the sigmoid mucosa and submucosa (37 (9 3) and 15 (3-5) pmol/g, respectively) and showed low, but consistent concentrations in the muscle (mid sigmoid: 2-2 (0 7) pmol/g, upper anal canal: 1 5 (0 8)). Starting in the distal sigmoid colon, a distinct peak oftissue NPY was revealed, which was most striking in the muscle (of mid sigmoid: 16 (3-9) pmol/g, upper rectum: 47 (7-8), anal sphincter: 58 (14)). -

Neuroendocrine Carcinomas of the Digestive Tract: What Is New?

cancers Review Neuroendocrine Carcinomas of the Digestive Tract: What Is New? Anna Pellat 1,*, Anne Ségolène Cottereau 2, Benoit Terris 3 and Romain Coriat 1 1 Gastroenterology and Digestive Oncology Unit, Cochin Teaching Hospital, AP-HP, Université de Paris, 27 rue du Faubourg Saint Jacques, 75014 Paris, France; [email protected] 2 Nuclear Medicine Department, Cochin Teaching Hospital, AP-HP, Université de Paris, 27 rue du Faubourg Saint Jacques, 75014 Paris, France; [email protected] 3 Pathology Department, Cochin Teaching Hospital, AP-HP, Université de Paris, 27 rue du Faubourg Saint Jacques, 75014 Paris, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: In this narrative review, we describe the current data and management of neu- roendocrine carcinomas (NEC) of the digestive tract. These tumors are very rare and suffer from a lack of clinical trials which would allow for standardized therapeutic management. To date, most guidelines come from studies in small-cell lung cancer, which is a similar entity in the lung. The incidence of NEC is rising and their prognostic is very low, underlying the urgent need for more trials to help define their best management. Abstract: Neuroendocrine carcinomas (NEC) are rare tumors with a rising incidence. They show poorly differentiated morphology with a high proliferation rate (Ki-67 index). They frequently arise in the lung (small and large-cell lung cancer) but rarely from the gastrointestinal tract. Due to their rarity, very little is known about digestive NEC and few studies have been conducted. Therefore, most of therapeutic recommendations are issued from work on small-cell lung cancers (SCLC). -

Internal Anal Sphincter

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.43.231.569 on 1 October 1968. Downloaded from Arch. Dis. Childh., 1968, 43, 569. Internal Anal Sphincter Observations on Development and Mechanism of Inhibitory Responses in Premature Infants and Children with Hirschsprung's Disease E. R. HOWARD and H. H. NIXON From The Hospitalfor Sick Children, Great Ormond Street, London W.C.1 The relative importance of the internal and obstruction to constipation alone. During this external sphincters to the maintenance of tone in study physiological abnormalities were observed in the anal canal has been shown in previous studies of the reflexes of premature infants, which showed anal physiology (Gaston, 1948; Schuster et al., 1965; similarities to those seen in patients with Hirsch- Duthie and Watts, 1965). sprung's disease. On repeated examinations over The external sphincter is a striated muscle, but several days, however, the physiological responses shows continuous activity on electromyography. were found to change until normal reflexes were Inhibition and stimulation is mediated by spinal eventually established. cord reflexes, through the pudendal nerves and In order to help determine the nervous pathway sacral segments of the spinal cord (Floyd and Walls, through which the reflexes of the internal sphincter copyright. 1953; Porter, 1961). Voluntary control is possible are mediated, we have examined normal bowel over this part ofthe anal sphincter. and aganglionic bowel from cases of Hirschsprung's The internal sphincter is made up of smooth disease by pharmacological and histochemical muscle fibres, continuous with the muscle layers of methods. the rectal wall, and under resting conditions pro- vides most of the tone of the anal canal (Duthie and Physiological Study Watts, 1965). -

Aandp2ch25lecture.Pdf

Chapter 25 Lecture Outline See separate PowerPoint slides for all figures and tables pre- inserted into PowerPoint without notes. Copyright © McGraw-Hill Education. Permission required for reproduction or display. 1 Introduction • Most nutrients we eat cannot be used in existing form – Must be broken down into smaller components before body can make use of them • Digestive system—acts as a disassembly line – To break down nutrients into forms that can be used by the body – To absorb them so they can be distributed to the tissues • Gastroenterology—the study of the digestive tract and the diagnosis and treatment of its disorders 25-2 General Anatomy and Digestive Processes • Expected Learning Outcomes – List the functions and major physiological processes of the digestive system. – Distinguish between mechanical and chemical digestion. – Describe the basic chemical process underlying all chemical digestion, and name the major substrates and products of this process. 25-3 General Anatomy and Digestive Processes (Continued) – List the regions of the digestive tract and the accessory organs of the digestive system. – Identify the layers of the digestive tract and describe its relationship to the peritoneum. – Describe the general neural and chemical controls over digestive function. 25-4 Digestive Function • Digestive system—organ system that processes food, extracts nutrients, and eliminates residue • Five stages of digestion – Ingestion: selective intake of food – Digestion: mechanical and chemical breakdown of food into a form usable by -

Electrophysiological Studies the Antrum Muscle Fibers of the Guinea

Electrophysiological Studies of the Antrum Muscle Fibers of the Guinea Pig Stomach H. KURIYAMA, T. OSA, and H. TASAKI Downloaded from http://rupress.org/jgp/article-pdf/55/1/48/1244765/48.pdf by guest on 29 September 2021 From the Department of PhysiologT,Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Kyushu University, Fukuoka,Japan AB STRAC T The membrane potentials of single smooth muscle fibers of various regions of the stomach were measured, and do not differ from those measured in intestinal muscle. Spontaneous slow waves with superimposed spikes could be recorded from the longitudinal and circular muscle of the antrum. The develop- ment of tension was preceded by spikes but often tension appeared only when the slow waves were generated. Contracture in high K solution developed at a critical membrane potential of --42 my. MnCI~ blocked the spike generation, then lowered the amplitude of the slow wave. On the other hand, withdrawal of Na +, or addition of atropine and tetrodotoxin inhibited the generation of most of the slow waves but a spike could still be elicited by electrical stimula- tion. Prostigmine enhanced and prolonged the slow wave; acetylcholine de- polarized the membrane without change in the frequency of the slow waves. Chronaxie for the spike generation in the longitudinal muscle of the antrum was 30 msec and conduction velocity was 1.2 cm/sec. The time constant of the foot of the propagated spike was 28 reset. The space constants measured from the longitudinal and circular muscles of the antrum were 1.1 mm and 1.4 into, respectively. INTRODUCTION The early investigations of mammalian stomach muscle suggested that mem- brane activity consisted of spike and slow wave components (Alvarez and Mahoney, 1922; Richter, 1923; Bozler, 1938, 1942; and Ichikawa and Bozler, 1955; Daniel, 1965). -

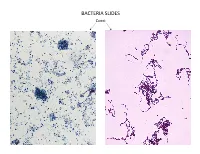

Bacteria Slides

BACTERIA SLIDES Cocci Bacillus BACTERIA SLIDES _______________ __ BACTERIA SLIDES Spirilla BACTERIA SLIDES ___________________ _____ BACTERIA SLIDES Bacillus BACTERIA SLIDES ________________ _ LUNG SLIDE Bronchiole Lumen Alveolar Sac Alveoli Alveolar Duct LUNG SLIDE SAGITTAL SECTION OF HUMAN HEAD MODEL Superior Concha Auditory Tube Middle Concha Opening Inferior Concha Nasal Cavity Internal Nare External Nare Hard Palate Pharyngeal Oral Cavity Tonsils Tongue Nasopharynx Soft Palate Oropharynx Uvula Laryngopharynx Palatine Tonsils Lingual Tonsils Epiglottis False Vocal Cords True Vocal Cords Esophagus Thyroid Cartilage Trachea Cricoid Cartilage SAGITTAL SECTION OF HUMAN HEAD MODEL LARYNX MODEL Side View Anterior View Hyoid Bone Superior Horn Thyroid Cartilage Inferior Horn Thyroid Gland Cricoid Cartilage Trachea Tracheal Rings LARYNX MODEL Posterior View Epiglottis Hyoid Bone Vocal Cords Epiglottis Corniculate Cartilage Arytenoid Cartilage Cricoid Cartilage Thyroid Gland Parathyroid Glands LARYNX MODEL Side View Anterior View ____________ _ ____________ _______ ______________ _____ _____________ ____________________ _____ ______________ _____ _________ _________ ____________ _______ LARYNX MODEL Posterior View HUMAN HEART & LUNGS MODEL Larynx Tracheal Rings Found on the Trachea Left Superior Lobe Left Inferior Lobe Heart Right Superior Lobe Right Middle Lobe Right Inferior Lobe Diaphragm HUMAN HEART & LUNGS MODEL Hilum (curvature where blood vessels enter lungs) Carina Pulmonary Arteries (Blue) Pulmonary Veins (Red) Bronchioles Apex (points