Disaster Risk Management for Communities © JM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Promoting Disaster Risk Reduction to Save Lives and Reduce Its Impacts WHO WE ARE

Photo: GTZ Promoting Disaster Risk Reduction to save lives and reduce its impacts WHO WE ARE he International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (ISDR) is a strategic framework adopted by United Nations Member States in 2000. The ISDR guides and coordinates theT efforts of a wide range of partners to achieve a substantive reduction in disaster losses. It aims to build resilient nations and communities as an essential condition for sustainable development. The United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR) is the secretariat of the ISDR system. The ISDR system comprises numerous organizations, States, intergovernmental and nongovernmental organizations, financial institutions, technical bodies and civil society, which work together and share information to reduce disaster risk. UNISDR serves as the focal point for the implementation of the Hyogo Framework for Action (HFA) – a ten year plan of action adopted in 2005 by 168 governments to protect lives and livelihoods against disasters. Photo: Jean P. Lavoie Disaster Risk Reduction Communities will always face natural hazards. Current disasters, however, are often a direct result of, or are exacerbated by, human activities. Such activities are changing the Earth’s natural balance, interfering like never before with the atmosphere, oceans, polar caps, forest cover and biodiversity, as well as other natural resources which make our world a habitable place. Furthermore, we are also putting ourselves at risk in ways that are less visible. Because natural hazards can affect anybody, disaster risk reduction is everybody’s responsibility. Disasters are not natural and can often be prevented. Economic resources, political will and a shared sense of hope form part of our collective protection from calamities. -

Natural Disasters in the Middle East and North Africa

Natural Disasters in Public Disclosure Authorized the Middle East and North Africa: A Regional Overview Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized January 2014 Urban, Social Development, and Disaster Risk Management Unit Sustainable Development Department Middle East and North Africa Natural Disasters in the Middle East and North Africa: A Regional Overview © 2014 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org All rights reserved 1 2 3 4 13 12 11 10 This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundar- ies, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorse- ment or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Recon- struction and Development / The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone: 978-750-8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. -

Thematic Sheet on Disaster Risk Reduction

H E T E M R E A T H I P C S 2 S H E E T Disaster Risk Reduction Sphere Thematic Sheets (TS) explain Sphere’s relevance for a specific theme. Here, we encourage Sphere users to mainstream Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) into their work and highlight to DRR specialists how Sphere supports their work. The Sphere Handbook does not explicitly mention DRR in its principles and standards. However, there is a direct and strong link between the two. This TS gives a brief overview of the concept of DRR and explores the mutual relevance of Sphere and DRR activities, common principles and approaches anchored in both, as well as a focus on Sphere’s technical chapters. The document is complemented by further online content. Mainstreaming Disaster Risk Reduction in Emergency Response While Sphere standards focus on the disaster response phase, they need to be solidly anchored and integrated in prevention, mitigation, preparedness, and recovery activities: “Relief aid must strive to reduce future vulnerabilities to disaster as well as meeting basic needs” (NGO Code of Conduct, Principle 8) Definition:Disaster risk reduction (DRR) is the concept and practice of reducing the risk of disaster through systematic efforts to analyse and manage causal factors. It includes reducing exposure to hazards, lessening the vulnerability of people and property, wise management of land and the environment, and improving preparedness for adverse events (Sphere definition of DRR). This implies the following key elements of DRR*: (1) Analysis of risks, vulnerabilities and capacities, (2) Reduction of exposure, (3) Reduction of vulnerabilities and (4) Enhancing capacities *please see online glossary for definitions of various DRR-related terms used in this TS Disasters related with natural hazards are increasing The SFDRR also highlights the need to mainstream in frequency and intensity, many of them exacerbated disaster risk reduction in the full disaster management by climate change. -

Roots for Resilience: a Health Emergency Risk Profile of the South-East Asia Region

Roots for Resilience: Resilience: for Roots A Health Emergency Risk Profile of the South-East Asia Region of Risk Profile Emergency A Health Trees, a symbol of resilience The book uses the tree of life, which is an archetypal central theme across all cultures, including in the This book provides a well-researched, WHO South-East Asia Region. The tree is therefore documented and illustrated analysis of a symbol of resilience with its well-entrenched and risks, threats, vulnerabilities and coping nourished roots. It survives wars, pandemics and capacities in the event of disasters, catastrophes while continuing to grow, shoot new epidemics and other calamities in the leaves and bear fruit. countries of the WHO South-East Roots for Resilience Asia Region. The oak tree used on the cover is known to be sturdy and resilient. Different tree motifs are used as These risks are then analysed through separators. The pine tree is rooted at high altitudes the lens of health status and capacity for but survives extremities of climate. Similarly, A Health Emergency Risk Profile emergency management across several mangroves can resist floods and bamboo does not hazards. The book aims to draw up break easily even with strong winds. The use of of the South-East Asia Region action points and recommendations to roots elsewhere reiterates the need to strengthen the address these risks in the immediate-, fundamentals—health systems, health workforce, medium- and long term, especially at the infrastructure and capacities for health emergency subnational level. risk management. Roots for Resilience A Health Emergency Risk Profile of the South-East Asia Region Roots for resilience: a health emergency risk profile of the South-East Asia Region ISBN 978-92-9022-609-3 © World Health Organization 2017 Some rights reserved. -

Issue Brief: Disaster Risk Governance Crisis Prevention and Recovery

ISSUE BRIEF: DISASTER RISK GOVERNANCE CRISIS PREVENTION AND RECOVERY United Nations Development Programme “The earthquake in Haiti in January 2010 was about the same magnitude as the February 2011 earthquake in Christchurch, but the human toll was significantly higher. The loss of 185 lives in Christchurch was 185 too many. However, compared with the estimated 220,000 plus killed in Haiti in 2010, it becomes evident that it is not the magnitude of the natural hazard alone that determines its impact.” – Helen Clark, UNDP Administrator Poorly managed economic growth, combined with climate variability and change, is driving an overall rise in global disaster Around the world, it is the poor who face the greatest risk from risk for all countries. disasters. Those affected by poverty are more likely to live in drought and flood prone regions, and natural hazards are far Human development and disaster risk are interlinked. Rapid more likely to hurt poor communities than rich ones. economic and urban development can lead to growing Ninety-five percent of the 1.3 million people killed and the 4.4 concentrations of people in areas that are prone to natural billion affected by disasters in the last two decades lived in developing countries, and fewer than two per cent of global hazards. The risk increases if the exposure of people and assets deaths from cyclones occur in countries with high levels of to natural hazards grows faster than the ability of countries to development. improve their risk reduction capacity. DISASTER RISK REDUCTION AND GOVERNANCE In the context of risk management, this requires that the general public are sufficiently informed of the natural hazard risks they are exposed to and able to take necessary The catastrophic impact of disasters is not ‘natural.’ Disasters are precautions. -

Disaster Risk-Informed and Resilient Covid-19 Recovery

DISASTER RISK-INFORMED AND RESILIENT COVID-19 RECOVERY Virtual Side Event at the 75 th Session of the General Assembly Second Committee 3pm-5pm EDT – Thursday 15 October 2020 Organized by the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) in collaboration with the International Labour Organization (ILO), the Office of the High Representative for LDCs, LLDCs and SIDS (OHRLLS), and UN Women CONCEPT NOTE SETTING THE SCENE Today’s risk landscape is rapidly changing, and risk has become progressively more systemic. New interactions between environmental, economic, technological and biological risks are emerging in ways that were not anticipated. One hazard can trigger another with cascading impacts across systems and borders and devastating impacts on progress across the SDGs. However, policies, institutions and financing remain focused on preparing for and responding to disasters, rather than preventing the creation of risk and subsequent losses. To achieve the SDGs, current, emerging and future risks need to be considered in policy and investment decisions in all sectors. The COVID-19 pandemic and the climate crisis exemplify the systemic nature of risk and the potential for cascading impacts. COVID-19 has triggered an unprecedented social and economic catastrophe on a global scale. Decades of development progress have unraveled, and poverty and inequality, particularly gender inequality, have deepened. As a consequence, vulnerability and exposure to other hazards, including the intensifying climate crisis, have greatly increased with impacts foreseen long into the future. While these hazards and risks affect all countries, the poorest and most exposed and vulnerable people, communities and countries bear the brunt. Despite strong commitment to disaster risk reduction, LDCs, LLDCs, and SIDS continue to suffer disproportionately high losses in human and economic terms owing to disasters. -

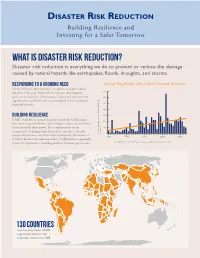

Disaster Risk Reduction Building Resilience and Investing for a Safer Tomorrow

DISASTER RISK REDUCTION Building Resilience and Investing for a Safer Tomorrow What is Disaster Risk Reduction? Disaster risk reduction is everything we do to prevent or reduce the damage caused by natural hazards like earthquakes, floods, droughts, and storms. Responding to a Growing Need Global Population Affected by Natural Disasters Natural disasters affect hundreds of millions of people around 700 the globe every year. With each new disaster, development gains are threatened as infrastructure is destroyed and economic 600 opportunities and livelihoods are interrupted or lost, leading to increased poverty. 500 400 Building Resilience 300 USAID responds to natural disasters around the world, saving 200 lives, protecting livelihoods, and working to reduce the economic losses caused by these events. Just as importantly, we are 100 committed to helping people lessen their exposure to hazards, Reported Number of People Affected Affected Reported Number of People (in Millions) 0 prepare for disasters, and better withstand shocks. The lessons of 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 USAID’s disaster risk reduction efforts worldwide have repeatedly shown the importance of building resilience in hazard-prone areas. Source: EM-DAT - The OFDA/CRED International Disaster Database, www.emdat.be, April 2014 130 COUNTRIES have benefited from USAID- supported disaster risk reduction efforts since 1989. USAID’S DISASTER RISK REDUCTION PROGRAMS SAVE LIVES Strengthening Early Warning Since 1989, we have helped establish 17 global, regional, or national early warning systems for drought, volcanoes, cyclones, and floods. These early warning systems work. For example, in 2013, warnings issued days prior to Cyclone Phailin’s arrival in India gave local authorities time to coordinate preparedness measures, including the evacuation of 1 million people living in coastal areas. -

(INCLUDING PANDEMICS) INTO DRR PLANNING Annex

INTEGRATING BIOLOGICAL HAZARDS (INCLUDING PANDEMICS) INTO DRR PLANNING Annex Team Members Rajib Shaw, Keio University and Resilience Innovation Knowledge Academy (RIKA) Ranit Chatterjee, Resilience Innovation Knowledge Academy (RIKA) Ambika Dabral, Resilience Innovation Knowledge Academy (RIKA) Advisors Emily Chan, Chinese University of Hong Kong, China Antonia Loyzaga, National Resilience Council, the Philippines Yong-kyun Kim, Ministry of Interior and Safety, Republic of Korea ii | Page Table of Contents 1. Background ............................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Biological hazards ..................................................................................................................................... 2 3. Content review ......................................................................................................................................... 5 3.1 Regional DRR and biological hazards/ public health response plans/ agreements ........................ 5 3.1.1 The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) ............................................................. 6 3.1.2 European Union (EU) ............................................................................................................... 7 3.2 National DRR and biological hazards/ public health response plans ............................................ 11 3.2.1 Germany ................................................................................................................................ -

(COVID-19) Pandemic: an Opportunity for a Systemic Approach to Disaster Risk for the Caribbean

COVID-19 Report ECLAC-UNDRR March 2021 The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: an opportunity for a systemic approach to disaster risk for the Caribbean Foreword by the Executive Secretary of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) The COVID-19 pandemic is a disaster that combines a biological threat with various vulnerabilities, such as the organizational and response Contents capacity of health systems, overcrowding, informality, social work Foreword by the Executive Secretary of the practices, and public transport. Disasters of this origin are not unknown Economic Commission for Latin America in Latin America and the Caribbean. Dengue and cholera have caused and the Caribbean (ECLAC) .................................1 the most epidemics in the region in the last fifty years. However, unlike other threats such as earthquakes, hurricanes and floods, which last Foreword by the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Disaster for minutes, days, or weeks, an epidemic can last for years. In 2020, Risk Reduction .....................................................3 COVID-19 affected all the countries in the region. Introduction ...........................................................4 The human and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic are unprecedented. According to World Health Organization (WHO) figures, I. Socioeconomic effects of COVID-19 by November 2020 it had caused more than 18 times more deaths than on the Caribbean .............................................5 all the epidemics that took place in Latin America and the Caribbean II. Towards a systemic approach to between 1970 and 2019. Furthermore, these deaths account for 63% of disaster risk in the Caribbean ......................14 all those caused by disasters in the region in the same period. -

FAO Disaster Risk Reduction for Food and Nutrition Security Framework Programme

The urgency to support resilient livelihoods: FAO Disaster Risk Reduction for Food and Nutrition Security Framework Programme Cristina Amaral1, Stephan Baas2 and Sylvie Wabbes1 1 Technical Cooperation Department; 2 Natural Resource Management and Environment Department , FAO, Rome DISASTER RISK REDUCTION IN THE CONTEXT OF CLIMATE CHANGE AND FOOD INSECURITY The multiple threats to food and nutrition security, their negative and cumulative impact, and the clear links between shocks and hunger reveal the fragility of current food pro- duction systems (and also of sustainable development) and their vulnerability to disasters, crises and conflicts. The Special Report on Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to advance climate change adaptation (SREX) stresses the interaction of climatic, environmental and human factors leading to impact and disaster. The character and severity of impacts and of risks depend on the shock (or extremes) themselves but also on the expo- sure (presence of people; livelihoods, environmental services and resources; infrastructure; or economic, social or cultural assets in places that could be adversely affected) and vulner- ability (the propensity or predisposition to be adversely affected) (IPCC, 2012). Disasters have adversely affected the lives and livelihoods of millions over the past years with particular deleterious consequences for the poor and politically marginalized. The impacts of the catastrophic earthquake in Haiti in January 2010 and floods in Pakistan in July 2010 show how disaster risk and poverty are closely interlinked. The 2011 Horn of Africa drought crisis also stresses the interconnection between natural disaster and conflict situations, magnifying the impact of the drought. Meanwhile, in 2011, floods in Australia, the earthquake in Christchurch, New Zealand, and the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster wreaking havoc in northeastern Japan are a stark reminder that developed countries are also very exposed. -

Mainstreaming Disaster Risk Reduction and Adaptation to Climate Change

Mainstreaming Disaster Risk Reduction and Adaptation to Climate Change Executive Secretariat for Integral Development Washington, DC 2014 RIGHTS OF THE AUTHOR© (2014) General Secretariat of the Organization of American States (OAS). Published by the Department of Sustainable Development. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Conventions. No portion of the contents may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher and the General Secretariat of the OAS. OAS Cataloging-in-Publication Data Organization of American States. Department of Sustainable Development. Mainstreaming disaster risk reduction and adaptation to climate change. p. : ill. ; cm. (OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.D/XXIII.20) ISBN 978-0-8270-6140-8 1. Emergency management. 2. Disaster relief. 3. Natural disasters--Risk Assessment. 4. Climatic changes. I. Title. II. Organization of American States. Executive Secretariat for Integral Development. III. Series. OEA/Ser.D/XXIII.20 The views expressed herein are presented for informational purposes only and do not represent the opinions or official positions of the Organization of American States, its General Secretariat, or any of its member States. José Miguel Insulza Secretary General V. Sherry Tross Executive Secretary for Integral Development Preface The Organization of American States (OAS) brings together all 35 independent states of the Americas and constitutes the main political, juridical, and social governmental forum in the Hemisphere. The OAS uses a four-pronged approach to effectively implement its essential purposes, based on its main pillars as established in the OAS Charter: democracy, human rights, security, and development through dialogue and cooperation among its member States. -

Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction and COVID-19

Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction and COVID-19 © UNDRR – United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction About UNDRR UNDRR (formerly UNISDR) is the United Nations focal point for disaster risk reduction. UNDRR oversees the implementation of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030, supporting countries in its implementation, monitoring and sharing what works in reducing existing risk and preventing the creation of new risk UNDRR brings governments, partners and communities together to reduce disaster risk and losses to ensure a safer, more sustainable future. © UNDRR – United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction Sendai Framework for DRR Expected outcome: The substantial reduction of disaster risk and losses in lives, livelihoods and health and in the economic, physical, social, cultural and environmental assets of persons, businesses, communities and countries. 4 Priority areas ▪ Understanding disaster risk ▪ Strengthening disaster risk governance ▪ Investing in disaster risk reduction ▪ Enhancing disaster preparedness, build back better & recovery 7 Global targets © UNDRR – United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction Contributing to the UN efforts • Guidance to UN Country Teams • Addressing COVID-19 through Issue-based coalitions • Promoting risk-informed and resilient COVID-19 recovery “ The COVID-19 pandemic has brought renewed attention to the importance of strengthening disaster risk reduction.” “COVID-19 has shown us that systemic risk requires international cooperation.” Antonio Guterres