Saga of Bengal Partition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-Kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L

Western Washington University Western CEDAR A Collection of Open Access Books and Books and Monographs Monographs 2008 Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L. Curley Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks Part of the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Curley, David L., "Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal" (2008). A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs. 5. https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Books and Monographs at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents Acknowledgements. 1. A Historian’s Introduction to Reading Mangal-Kabya. 2. Kings and Commerce on an Agrarian Frontier: Kalketu’s Story in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 3. Marriage, Honor, Agency, and Trials by Ordeal: Women’s Gender Roles in Candimangal. 4. ‘Tribute Exchange’ and the Liminality of Foreign Merchants in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 5. ‘Voluntary’ Relationships and Royal Gifts of Pan in Mughal Bengal. 6. Maharaja Krsnacandra, Hinduism and Kingship in the Contact Zone of Bengal. 7. Lost Meanings and New Stories: Candimangal after British Dominance. Index. Acknowledgements This collection of essays was made possible by the wonderful, multidisciplinary education in history and literature which I received at the University of Chicago. It is a pleasure to thank my living teachers, Herman Sinaiko, Ronald B. -

Prof. Kanu BALA-Bangladesh: Professor of Ultrasound and Imaging

Welcome To The Workshops Dear Colleague, Due to increasing demands for education and training in ultrasonography, World Federation for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology has established its First "WFUMB Center of Excellence" in Dhaka in 2004. Bangladesh Society of Ultrasonography is the First WFUMB Affiliate to receive this honor. The aims of the WFUMB COE is to provide education and training in medical ultrasonography, to confer accreditation after successful completion of necessary examinations and to accumulate current technical information on ultrasound techniques under close communication with other Centers, WFUMB and WHO Global Steering Group for Education and Teaching in Diagnostic Imaging. 23 WFUMB Center of Education Workshop of the World Federation for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology will be held jointly in the City of Dhaka on 6 & 7 March 2020. It is a program of “Role of Ultrasound in Fetal Medicine” and will cover some new and hot areas of diagnostic ultrasound. It’s First of March and it is the best time to be in Dhaka. So block your dates and confirm your registration. Yours Cordially Prof. Byong Ihn Choi Prof. Mizanul Hasan Director President WFUMB COE Task Force Bangladesh Society of Ultrasonography Prof. Kanu Bala Prof. Jasmine Ara Haque Director Secretary General WFUMB COE Bangladesh Bangladesh Society of Ultrasonography WFUMB Faculty . Prof. Byung Ihn Choi-South Korea: Professor of Radiology. Expert in Hepatobiliary Ultrasound, Contrast Ultrasound and Leading Edge Ultrasound. Director of the WFUMB Task Force. Past President of Korean society of Ultrasound in Medicine. Past President of the Asian Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology. -

1. Introduction

Notes 1. Introduction 1. ‘Diaras and Chars often first appear as thin slivers of sand. On this is deposited layers of silt till a low bank is consolidated. Tamarisk bushes, a spiny grass, establish a foot-hold and accretions as soon as the river recedes in winter; the river flows being considerably seasonal. For several years the Diara and Char may be cultivable only in winter, till with a fresh flood either the level is raised above the normal flood level or the accretion is diluvated completely’ (Haroun er Rashid, Geography of Bangladesh (Dhaka, 1991), p. 18). 2. For notes on geological processes of land formation and sedimentation in the Bengal delta, see W.W. Hunter, Imperial Gazetteer of India, vol. 4 (London, 1885), pp. 24–8; Radhakamal Mukerjee, The Changing Face of Bengal: a Study in Riverine Economy (Calcutta,1938), pp. 228–9; Colin D. Woodroffe, Coasts: Form, Process and Evolution (Cambridge, 2002), pp. 340, 351; Ashraf Uddin and Neil Lundberg, ‘Cenozoic History of the Himalayan-Bengal System: Sand Composition in the Bengal Basin, Bangladesh’, Geological Society of America Bulletin, 110 (4) (April 1998): 497–511; Liz Wilson and Brant Wilson, ‘Welcome to the Himalayan Orogeny’, http://www.geo.arizona.edu/geo5xx/ geo527/Himalayas/, last accessed 17 December 2009. 3. Harry W. Blair, ‘Local Government and Rural Development in the Bengal Sundarbans: an Enquiry in Managing Common Property Resources’, Agriculture and Human Values, 7(2) (1990): 40. 4. Richard M. Eaton, The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier 1204–1760 (Berkeley and London, 1993), pp. 24–7. 5. -

Natore Raj - Its Rise, Stability and Estate Management

96 Chapter-HI Natore Raj - Its Rise, Stability and Estate Management Natore is situated near the main road leading to Dhaka from Rajshahi. It is 30 miles east of Rajshahi. Natore town stands on the Narad river at the degree of latitude 24-6" north and 89-1 "east'. Natore was an important administrative central point during the reign of the Nawabs of Bengal. At the time of the British regime Natore was an important town of Rajshahi district. Natore had great importance as a business center. A great number of Europeans lived at Natore. In 1825 the district head quarter was shifted from Natore to Rampur-Boalia(Rajshahi) because the river Narod was silted up and dieses like malaria and dengu prevailed terribly^ . To realize the historical importance of Natore, it was made a subdivision in 1829 \ This historical Natore was the capital of Natore Raj family Natore and Natore Raj family were related inseparably. The glory of this place faded since the time of the downfall of the Natore Raj Family. Kamdev Moitra (Ray) was the ancestor of Natore Raj Family. At the beginning of tenth century, the Hindu Raja Adisur of Chandra family brought five well versed Brahmins in Bengal from Kanyakubja. This five persons were Narayan of Sandilya lineage, Dharadhar of Batsa lineage, Gautam of Bharadwaj lineage, and Parasar of Sadhan lineage and Susenmani of Kasyapa lineage. Kamdev Moitra was a member of the later generation of Susenmani of Kasyapa lineage". Kamdev Moitra was the tahsilder at Baruihati- Pargana under Raja Naranarayan Thakur of Puthia\ His dwelling place was at the village Amhati situated near Natore town. -

Raishahi Zamindars: a Historical Profile in the Colonial Period [1765-19471

Raishahi Zamindars: A Historical Profile in the Colonial Period [1765-19471 Thesis Submitted to the University of North Bengal, Darjeeling, India for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, History by S.iVI.Rabiul Karim Associtate Professor of Islamic History New Government Degree College Rajstiahi, Bangladesh /^B-'t'' .\ Under the Supervision of Dr. I. Sarkar Reader in History University fo North Bengal Darjeeling, West Bengal India Janiary.2006 18^62/ 2 6 FEB 4?eP. 354.9203 189627 26 FEB 2007 5. M. Rahiul Karitn Research Scholar, Associate Professor, Department of History Islamic History University of North Bengal New Government Degree College Darjeeling, West Bengal Rajshahi, Bangladesh India DECLARATION I hereby declare that the Thesis entitled 'Rajshahi Zamindars: A Historical Profile in the Colonial Period (1765-1947)' submitted by me for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of the Universit\' of North Bengal, is a record of research work done by me and that the Thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any other Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship and similar other tides. M^ Ro^JB^-vvA. VxQrVvvv S. M. Rabiul Karim (^ < o t • ^^ Acknowledgment I am grateful to all those who helped me in selecting such an interesting topic of research and for inspiring me to complete the present dissertation. The first person to be remembered in this connection is Dr. I. Sarkar, Reader, Department of History, University of North Bengal without his direct and indirect help and guidance it would not have been possible for me to complete the work. He guided me all along and I express my gratitude to him for his valuable advice and method that I could follow in course of preparation of the thesis. -

Download Download

Creative Space,Vol. 6, No. 2, Jan. 2019, pp. 85–100 Vol.-6 | No.-2 | Jan. 2019 Creative Space Journal homepage: https://cs.chitkara.edu.in/ Study of the Distinguishing Features of Mughal Mosque in Dhaka: A Case of Sat Gambuj Mosque Shirajom Monira Khondker Assistant Professor, Faculty of Architecture and Planning, Ahsanullah University of Science and Technology (AUST) Dhaka, Bangladesh. *Email: [email protected] ARTICLE INFORMATION ABSTRACT Received: August 8, 2018 Mosque is the main focal point of Islamic spirit and accomplishments. All over the world in the Revised: October 9, 2018 Muslim settlements mosque becomes an edifice of distinct significance which is introduced by Prophet Accepted: November 17, 2018 Muhammad (Sm.). Since the initial stage of Islam, Muslim architecture has been developed as the base point of mosque. Mosque architecture in medieval time uncovering clearly its sacred identity Published online: January 8, 2019 especially during the pre-Mughal and Mughal period in Bengal. Dhaka, the capital city of independent Bangladesh, is known as the city of mosques. The Mughal mosques of Dhaka are the exceptional example of mosque architecture wherever the ideas and used materials with distinguishing features Keywords: have been successfully integrated in the medieval context of Bengal. In this research study, the author Mughal Mosque, Dhaka city, Sat Gambuj selected a unique historical as well as Dhaka’s most iconic Mughal era Mosque named “Sat Gambuj Mosque, Architectural Features, Structure Mosque” (Seven Domed Mosque). The mosque, built in the 17th century, is a glowing illustration of and Decoration, Distinguishing Features. Mughal Architecture with seven bulbous domes crowning the roof of the mosque, covering the main prayer area. -

LIST of LICENSED BLOOD BANKS in INDIA * (February, 2015)

LIST OF LICENSED BLOOD BANKS IN INDIA * (February, 2015) Sr. State Total No. of Blood Banks No. 1. Andaman and Nicobar Islands 03 2. Andhra Pradesh 140 3. Arunachal Pradesh 13 4. Assam 76 5. Bihar 84 6. Chandigarh 04 7. Chhattisgarh 49 8. Dadra and Nagar Haveli 01 9. Daman and Diu 02 10. Delhi (NCT) 72 11. Goa 05 12. Gujarat 136 13. Haryana 79 14. Himachal Pradesh 22 15. Jammu and Kashmir 31 16. Jharkhand 54 17. Karnataka 185 18. Kerala 172 19. Lakshadweep 01 20. Madhya Pradesh 144 21. Maharashtra 297 22. Manipur 05 23. Meghalaya 07 24. Mizoram 10 25. Nagaland 06 26. Odisha(Orissa) 91 27. Puducherry 18 28. Punjab 103 29. Rajasthan 102 30. Sikkim 03 31. Tamil Nadu 304 32. Telangana 151 33. Tripura 08 34. Uttar Pradesh 240 35. Uttarakhand 24 36. West Bengal 118 Total 2760 * List as received from the Zonal / Sub-Zonal Offices of CDSCO. Sr. No Sr.No Name and address of the Blood bank Central-wise State-wise (1). ANDAMAN & NICOBAR 1. 1) M/s G.B Pant Hospital, Atlanta Point, Port Blair-744104 2. 2) M/s I.N.H.S. Dhanvantri, Minni Bay, Port Blair-744103 3. 3) M/s Pillar Health Centre, Lamba Line, P.B. No.526, P.O.- Junglighat, Port Blair-744103 (2). ANDHRA PRADESH 4. 1) A.P.Vidya Vidhana Parishad Community Hospital Blood Bank, Hospital Road, Gudur-524101, Nellore Dist. 5. 2) A.S.N. Raju Charitable Trust Blood Bank, Door No. 24-1-1, R.K. Plaza (Sarovar Complex), J.P. -

ANCIENT RIGHTS and FUTURE COMFORT Bihar, the Bengal

LONDON STUDIES ON SOUTH ASIA NO. 13 ANCIENT RIGHTS AND FUTURE COMFORT Bihar, the Bengal Tenancy Act of 1885, and British Rule in India P.G. Robb School of Oriental and African Studies, London This book was published in 1997 by Curzon Press, now Routledge, and is reproduced in this repository by permission. The deposited copy is from the author’s final files, and pagination differs slightly from the publisher’s printed version. Therefore the index is not included. © Peter Robb 1997 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form without written permission from the publishers. ISBN 0-7007-0625-9 Chapter Five Custom and the law We may conclude from chapter four, unsurprisingly, that the 1885 Act originated in colonial perceptions. Noteworthy in the debate was the paucity of direct justification for the favourable prognosis—the future comfort—which was promised as a result of the reforms. Instead, alongside the cases made for historical legitimacy and present poverty and oppression, an adverse trajectory was presented: the fate of tenants since the permanent settlement. This appeared as a professedly factual account, but contained an implied counterfactual (what would have happened if tenant rights had been preserved by law), which reduced the need to verify either the past ruin and its causes, or the future pro- mise and its means. At issue, instead, was the subject of this chapter, the role of law and custom—as explanations or as remedies for present conditions, and in relation to a goal of improvement. -

Strategies to Integrate the Mughal Settlements in Old Dhaka

Frontiers of Architectural Research (2013) 2, 420–434 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com www.elsevier.com/locate/foar CASE STUDY Strategies to integrate the Mughal settlements in Old Dhaka Mohammad Sazzad Hossainn Department of Architecture, Southeast University, Dhaka 1208, Bangladesh Received 18 March 2013; received in revised form 19 July 2013; accepted 1 August 2013 KEYWORDS Abstract Mughal settlement; The Mughal settlements are an integral part of Old Dhaka. Uncontrolled urbanization, changes Urban transformation; in land use patterns, the growing density of new settlements, and modern transportation have Integration brought about rapid transformation to the historic fabric of the Mughal settlements. As a result, Mughal structures are gradually turning into isolated elements in the transforming fabric. This study aims to promote the historic quality of the old city through clear and sustainable integration of the Mughal settlements in the existing fabric. This study attempts to analyze the Mughal settlements in old Dhaka and correspondingly outline strategic approaches to protect Mughal artifacts from decay and ensure proper access and visual exposure in the present urban tissue. & 2013. Higher Education Press Limited Company. Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V. Open access under CC BY-NC-ND license. 1. Introduction Dhaka was established as a provincial capital of Bengal during the Mughal period. The focal part of Mughal City is currently located in old Dhaka, which has undergone successive transfor- mations. The Mughal settlements are considered the historic core of Mughal City. The old city covers an area of 284.3 acres nTel.: +880 1715 010683. with a population of 8,87,000. -

A Village in the Bishnupur Subdivision, Situated 7 Miles North-West of Bishnupur

CHAPTER XIV GAZETTEER Ajodhya— A village in the Bishnupur subdivision, situated 7 miles north-west of Bishnupur. The village contains a charitable dispensary and the residence of one of the leading zamindars of the district. Ambikanagar— A village in the Bankura subdivision, situated on the south bank of the Kasai river, 10 miles south-west of Khatra, with which it is connected by an unmetalled road. This village has given its name to a pargana extending over 151 square miles, and was formerly the headquarters of an ancient family of zamindars, whose history has been given in the article on Dhalbhum. Bahulara— A village in the Bankura subdivision, situated on the south bank of the Dhalkisor river, 12 miles south-east of Bankura and 3 miles north of Onda. It contains a temple dedicated to Mahadeo Siddheswar, said to have been built by the Raja of Bishnupur, which Mr. Beglar has described as the finest brick temple in the district, and the finest though not the largest brick temple that he had seen in Bengal. He gives the following account of it in the Reports of the Archaeological Survey of India, Vol. VIII. "The temple is of brick, plastered; the ornamentation is carefully cut in the brick, and the plaster made to correspond to it. There are, however, ornaments on the plaster alone, but none inconsistent with the brick ornamentation below. I conclude, therefore, that the plaster formed a part of the original design. The mouldings of the basement are to a great extent gone, but from fragments here and there that exist, a close approximation can be made to what it was; some portions are, however, not recoverable. -

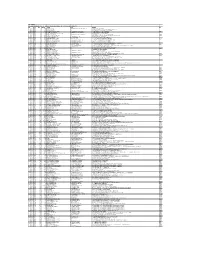

Dpid Folio Wno Net Div Name Fname Address Pin Physical

HIL LIMITED INTERIM DIVIDEND 2015-16 - UNPAID SHAREHOLDERS LIST AS ON 4TH MARCH 2016 DPID FOLIO WNO NET_DIV NAME FNAME ADDRESS PIN PHYSICAL 000002 68 6000.00 ANWARI BEGUM W/O NAWAB AKBARYARJUNG BAHADUR TROOP BAZAR,,,HYDERABAD PHYSICAL 000003 92 60.00 AMINA KHATOON N A 5-9-1101 OPP MUNICIPAL PARK,,GUNFOUNDRY,,,HYDERABAD PHYSICAL 000007 142 120.00 AZIZULLA SHARIEF N A F-4-837 NEAR RED HILLS MOSQUE,,,,HYDERABAD PHYSICAL 000010 171 240.00 NAWAB M. ABUL FATEH KHAN S/O. NAWAB SULTAN-UL-MULK FATEHBAGH,SANATHNAGAR,,HYDERABAD 500018 PHYSICAL 000011 184 120.00 AMEERALI RAHIMTULLA S/O ABDULLA HAJI RAHIMTULLA 66 ALEXANDRA ROAD,,,,SECUNDERABAD. PHYSICAL 000019 255 60.00 SAHEBZADI BASHEERUNNISA BEGUM N A AIWAN,,BEGUMPET,,,SECUNDERABAD. PHYSICAL 000024 284 720.00 DINA N. LAKDAWALLA D/O KAOSHUSWANJI D LAKDAWALA GOOL MANZIL,,72 SAPPERS LINES,,SECUNDERABAD 500003 PHYSICAL 000031 333 1800.00 FRAMROZ OOKERJI DINSHAW N A 5-8-47,FATHESULTAN LANE,,STATION ROAD,NAMPALLY,HYDERABAD 500001 PHYSICAL 000049 413 900.00 MOHAMED SULTANUDDIN S/O MOHAMED SULTAN 4-1-1/23,KING KOTHI,,HYDERABAD PHYSICAL 000051 424 240.00 M.E. NISAR AHMED S/O ALI MOHAMED 11-4-911 CHILAKALAGUDA,,,,SECUNDERABAD PHYSICAL 000053 434 360.00 MOHAMED ABDUL RASHEED N A 12-1-1048 NORTH LALLAGUDA,,,,SECUNDERABAD 500017 PHYSICAL 000054 436 180.00 MOHAMED ABDUL KAREEM S/O HAJI MOHD IBRAHIM KHAN E-12-584 SYEDALIGUDA,,KARWAN SAHOO,,,HYDERABAD PHYSICAL 000055 443 660.00 MOHAMED ZEENATH HUSSAIN S/O MOHAMMED YOUSUF 20-4-717 MOHELLA SHAH GUNJ,,,,HYDERABAD PHYSICAL 000057 450 120.00 MOHAMED FARIDUDDIN S/O MOHAMED QURBAN ALI MANJLAGUDA VILLAGE,,MADUR B.P.O.,,NARSAPUR TQ PHYSICAL 000058 456 150.00 MOHAMED KHAJA MIAN S/O SHAIK MASTAN 1166 BAZARGHAT,,NEAR KUTUB SHAHI MASZID,,NAMPALLY,,HYDERABAD PHYSICAL 000059 462 150.00 MOHAMED YOUSUF S/O KHATTAL AHMED 12-1-922/58,OLD FEELKHANA, ASIFNAGAR,,HYDERABAD 500028 PHYSICAL 000062 477 120.00 MIRZA RAZAK ALI BAIG S/O MIRZA MAHBOOB BAIG C/O. -

Report on Ahsan Manzil

AHSAN MANZIL By Zawad Ahmed Introduction: The Ahsan Manzil is located in Kumartoli, Dhaka, on the Buriganga River.It was the nawabs of Dhaka's private royal residence and kachari.It is located in Latif Complex, Islampur Rd, Dhaka, and has recently been converted into a historical hub.It was designed by Indo-Saracenic engineers.The construction of the royal residence began in 1859 and was completed in 1872.Ahsan Manzil is one of the country's most significant compositional landmarks.This structural fortune has been witnessed on multiple occasions in Bangladesh.The bulk of Nawab Khwaja salimullah's political activities revolved around this royal residence. The All India Muslim League was behind Ahsan Manzil.It was given the name Ahsan Manzil by Abdul Ghani in honor of his son Khwaja Ahsanullah.The decline of the Dhaka nawabs coincided with the decline of Ahsan Manzil. Collected From Wikipedia It was built on a 1 metre raised base, with the two-celebrated castle measuring 125.4m by 28.75m.The ground floor is 5 meters tall, while the first floor is 5.8 meters tall.Patios of ground floor stature can be found on both the northern and southern sides of the castle.Through the front nursery, an open, roomy flight of stairs has descended from the southern colonnade, which has been broadened up to the bank of the stream.Prior to the steps, there was a wellspring in the nursery that no longer exists.Two of the floors' open north and south verandas followed crescent curves. Marble covers the entire board.During construction, the square room on the ground floor was given a round shape with brickwork in the corners.