Structural and Ornamental Diatonic Harmony in Western Music, C.1700 – 1880

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Riemann's Functional Framework for Extended Jazz Harmony James

Riemann’s Functional Framework for Extended Jazz Harmony James McGowan The I or tonic chord is the only chord which gives the feeling of complete rest or relaxation. Since the I chord acts as the point of rest there is generated in the other chords a feeling of tension or restlessness. The other chords therefore must 1 eventually return to the tonic chord if a feeling of relaxation is desired. Invoking several musical metaphors, Ricigliano’s comment could apply equally well to the tension and release of any tonal music, not only jazz. Indeed, such metaphors serve as essential points of departure for some extended treatises in music theory.2 Andrew Jaffe further associates “tonic,” “stability,” and “consonance,” when he states: “Two terms used to refer to the extremes of harmonic stability and instability within an individual chord or a chord progression are dissonance and consonance.”3 One should acknowledge, however, that to the non-jazz reader, reference to “tonic chord” implicitly means triad. This is not the case for Ricigliano, Jaffe, or numerous other writers of pedagogical jazz theory.4 Rather, in complete indifference to, ignorance of, or reaction against the common-practice principle that only triads or 1 Ricigliano 1967, 21. 2 A prime example, Berry applies the metaphor of “motion” to explore “Formal processes and element-actions of growth and decline” within different musical domains, in diverse stylistic contexts. Berry 1976, 6 (also see 111–2). An important precedent for Berry’s work in the metaphoric dynamism of harmony and other parameters is found in the writings of Kurth – particularly in his conceptions of “sensuous” and “energetic” harmony. -

Accelerated Piano Technique and Music Theory Ii Course Syllabus

ACCELERATED PIANO TECHNIQUE AND MUSIC THEORY II COURSE SYLLABUS Course: Accelerated Piano Technique and Music Theory II Credit: One Carnegie Unit Course Description Accelerated Piano Technique and Music Theory II is required for graduation as a vocal music major. It is for students who have completed the requirements of Accelerated Piano Technique and Music Theory I and completes the prerequisite for all other theory classes. It satisfies the Piano Lab II requirement for vocal majors and the Music Theory II requirement for both vocal and instrumental majors. This course covers the rudiments of music theory and emphasizes basic musicianship skills in the areas of sight singing, ear training, and dictation. Basic piano fundamentals are explored: familiarization with keyboard theory, hand coordination, grand staff note reading, and an introduction to the standard intermediate piano literature. Content Standards DCPS music content standards make up the core skills, concepts and knowledge for Music Theory II: 1. Perform a variety of repertoire. 2. Improvise, compose, and arrange. 3. Read and notate music. 4. Listen, analyze, and evaluate. These standards are incorporated in the course outline below. Course Outline 1. Perform all tasks covered in Accelerated Piano Technique and Music Theory I, with emphasis on reading and writing fluently in treble and bass clefs including identification, notation, reading and writing of all leger line notes above and below the staff. 2. Identify and write all major and minor key signatures; explain and construct a diagram of the circle of fifths. 3. Identify on the page and by ear, sing*, write, and play on the piano keyboard: a. -

Promtional Sample Pages

The Fundamental Triad System A chord-first approach to jazz theory and practice Pete Pancrazi Copyright © 2014 by Pete Pancrazi All Rights Reserved www.petepancrazi.com Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................5 Chapter 1 The Simple Intervals .............................................................6 Chapter 2 The Major Keys .......................................................................13 Chapter 3 The Fundamental Triads .....................................................19 Chapter 4 Triads of the Major Scale .................................................... 27 Chapter 5 Extending the Triads with a 7th or 6th ........................... 32 Chapter 6 Extending the Triads of the Major Scale ...................... 39 Chapter 7 The 12-Bar Blues ...................................................................43 Chapter 8 Voice Leading ...........................................................................45 Chapter 9 Song Melody and the Blueprint .......................................51 Chapter 10 The Major II-V-I Progression ............................................54 Chapter 11 Compound Intervals .............................................................64 Chapter 12 Extending a Chord with a 9th, 11th or 13th ................68 Chapter 13 Modes or the Major Scale...................................................74 Chapter 14 Auxiliary Notes ........................................................................ 87 -

Further Considerations of the Continuous ^5 with an Introduction and Explanation of Schenker's Five Interruption Models

Further Considerations of the Continuous ^5 with an Introduction and Explanation of Schenker's Five Interruption Models By: Irna Priore ―Further Considerations about the Continuous ^5 with an Introduction and Explanation of Schenker’s Five Interruption Models.‖ Indiana Theory Review, Volume 25, Spring-Fall 2004 (spring 2007). Made available courtesy of Indiana University School of Music: http://www.music.indiana.edu/ *** Note: Figures may be missing from this format of the document Article: Schenker’s works span about thirty years, from his early performance editions in the first decade of the twentieth century to Free Composition in 1935.1 Nevertheless, the focus of modern scholarship has most often been on the ideas contained in this last work. Although Free Composition is indeed a monumental accomplishment, Schenker's early ideas are insightful and merit further study. Not everything in these early essays was incorporated into Free Composition and some ideas that appear in their final form in Free Composition can be traced back to his previous writings. This is the case with the discussion of interruption, a term coined only in Free Composition. After the idea of the chord of nature and its unfolding, interruption is probably the most important concept in Free Composition. In this work Schenker studied the implications of melodic descent, referring to the momentary pause of this descent prior to the achievement of tonal closure as interruption. In his earlier works he focused more on the continuity of the line itself rather than its tonal closure, and used the notion of melodic line or melodic continuity to address long-range connections. -

Harmonic Expectation in Twelve-Bar Blues Progressions Bryn Hughes

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 Harmonic Expectation in Twelve-Bar Blues Progressions Bryn Hughes Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC HARMONIC EXPECTATION IN TWELVE-BAR BLUES PROGRESSIONS By BRYN HUGHES A dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2011 The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Bryn Hughes defended on July 1, 2011. ___________________________________ Nancy Rogers Professor Directing Dissertation ___________________________________ Denise Von Glahn University Representative ___________________________________ Matthew Shaftel Committee Member ___________________________________ Clifton Callender Committee Member Approved: _____________________________________ Evan Jones, Chair, Department of Music Theory and Composition _____________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii To my father, Robert David Moyse, for teaching me about the blues, and to the love of my life, Jillian Bracken. Thanks for believing in me. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Before thanking anyone in particular, I would like to express my praise for the Florida State University music theory program. The students and faculty provided me with the perfect combination of guidance, enthusiasm, and support to allow me to succeed. My outlook on the field of music theory and on academic life in general was profoundly shaped by my time as a student at FSU. I would like to express my thanks to Richard Parks and Catherine Nolan, both of whom I studied under during my time as a student at the University of Western Ontario and inspired and motivated me to make music theory a career. -

Level 3 Scale Reference Sheet MP: 4 Scales – 2 Major and 2 Harmonic Minor

Level 3 Scale Reference Sheet MP: 4 scales – 2 major and 2 harmonic minor 1. Play Scale (As tetrachord or one octave, hands separate or together) 2. Play I and V chords (of the scale you just played) (Hands separate or together) 3. Play chord progression (of the scale you just played): (or I-V-I) (Hands separate or together) 4. Play arpeggio (of the scale you just played): 5. Applied Theory - Intervals: Play 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th in the keys of prepared scales up from tonic only, using appropriate black keys www.wendyspianostudio.com 76 Level 3 SCALE CHECKLIST C Major a minor G Major e minor D Major b minor A Major f# minor # E Major c minor # B Major g minor Gb Major eb minor Db Major bb minor Ab Major f minor Eb Major c minor b B Major g minor F Major d minor 77 Level 4 Scale Reference Sheet MP: 4 keys – 2 major and 2 minor (natural and harmonic minor forms) 1. Play Scale (One octave, hands separate or together) 2. Play Primary Chords in Root position (for the scale you just played), hands separate or together. For minor keys, use harmonic form. 3. Play inversions of the tonic triad up and down, hands separate or together: 4. Play chord Progression: (or I-IV-I-V-I) hands separate or together. In minor keys, use harmonic form. 5. Play 1 handed arpeggio: www.wendyspianostudio.com 78 Level Four, continued 6. Theory - Intervals: Play 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, and octave, in the keys of prepared scales, up only, beginning on any pitch in the scale. -

Syllabus Spring, 2020 Music 321 Elementary Piano 1 Section 13137 Lecture 13156 Lab Tuesdays 6:50-10:00 PM

Syllabus Spring, 2020 Music 321 Elementary Piano 1 Section 13137 Lecture 13156 Lab Tuesdays 6:50-10:00 PM Instructor: Ms. Claire Rydell E Mail: Ask questions and report absences: [email protected] Subject: Piano Class Office Hours: Tuesdays 6:15-6:50 PM Room M100 Textbooks: 1) Bastien Piano for Adults Book 1 (you do not need the CD’s), KJOS KP 1B ISBN 0-8497-7302-4. (about $15.95) 2) Rydell Music 321 Scales, Chords & Materials for Learning (about $15) AVAILABLE ONLY AT THE BOOKSTORE Ask for the coursebook at the cash register if it is not on the shelf. Get the books today. You MUST have the books at the next class. Other music stores include: Baxter Northrup 14534 Ventura Blvd 818-788-7510 Keyboard Concepts 5539 Van Nuys Blvd 818-787-0201 Sam Ash Music 20934 Roscoe Blvd 818-709-5650 Bring a pencil & eraser to class to write in your books. Write fingerings and counting in your music to help you play well. Please bring your own headset to class and a mini jack adapter that converts 1/8” to 1/4”inches (3.5 mm to 6.5 mm.) You need to have a metronome: you can download an app like MetroTimer. Student Learning Outcome: SLO #1: Student will be able to play beginning level piano technique, including one-octave scales and primary triad chord progressions in the following keys: C, G, D, A, and E Majors. SLO # 2: Student will be able to play beginning level piano repertoire. Course Objectives: Upon successful completion of the course, students will demonstrate skill in basic piano playing including correct posture and hand position, independence of fingers, locating notes on the keyboard in treble and bass clefs, understanding and performing basic rhythms and learning efficient methods for practicing. -

Accelerated Piano Technique and Music Theory Ii) Course Syllabus

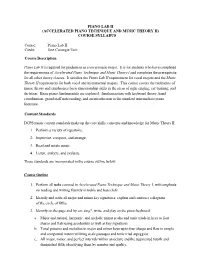

PIANO LAB II (ACCELERATED PIANO TECHNIQUE AND MUSIC THEORY II) COURSE SYLLABUS Course: Piano Lab II Credit: One Carnegie Unit Course Description Piano Lab II is required for graduation as a vocal music major. It is for students who have completed the requirements of Accelerated Piano Technique and Music Theory I and completes the prerequisite for all other theory classes. It satisfies the Piano Lab II requirement for vocal majors and the Music Theory II requirement for both vocal and instrumental majors. This course covers the rudiments of music theory and emphasizes basic musicianship skills in the areas of sight singing, ear training, and dictation. Basic piano fundamentals are explored: familiarization with keyboard theory, hand coordination, grand staff note reading, and an introduction to the standard intermediate piano literature. Content Standards DCPS music content standards make up the core skills, concepts and knowledge for Music Theory II: 1. Perform a variety of repertoire. 2. Improvise, compose, and arrange. 3. Read and notate music. 4. Listen, analyze, and evaluate. These standards are incorporated in the course outline below. Course Outline 1. Perform all tasks covered in Accelerated Piano Technique and Music Theory I, with emphasis on reading and writing fluently in treble and bass clefs. 2. Identify and write all major and minor key signatures; explain and construct a diagram of the circle of fifths. 3. Identify on the page and by ear, sing*, write, and play on the piano keyboard: a. Major and natural, harmonic, and melodic minor scales and tonic triads in keys to four sharps and flats using accidentals as well as key signatures b. -

2005: Boston/Cambridge

PROGRAM and ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS READ at the Twenty–Eighth Annual Meeting of the SOCIETY FOR MUSIC THEORY 10–13 November 2005 Hyatt Regency Cambridge Boston/Cambridge, Massachusetts 2 SMT 2005 Annual Meeting Edited by Taylor A. Greer Chair, 2005 SMT Program Committee Local Arrangements Committee David Kopp, Deborah Stein, Co-Chairs Program Committee Taylor A. Greer, Chair, Dora A. Hanninen, Daphne Leong, Joel Lester (ex officio), Henry Martin, Shaugn O’Donnell, Deborah Stein Executive Board Joel Lester, President William Caplin, President-Elect Harald Krebs, Vice President Nancy Rogers, Secretary Claire Boge, Treasurer Kofi Agawu Lynne Rogers Warren Darcy Judy Lochhead Frank Samarotto Janna Saslaw Executive Director Victoria L. Long 3 Contents Program…………………………………………………………........ 5 Abstracts………………………………………………………….…... 16 Thursday afternoon, 10 November Combining Musical Systems……………………………………. 17 New Modes, New Measures…………………………………....... 19 Compositional Process and Analysis……………………………. 21 Pedagogy………………………………………………………… 22 Introspective/ Prospective Analysis……………………………... 23 Thursday evening Negotiating Career and Family………………………………….. 24 Poster Session…………………………………………………… 26 Friday morning, 11 November Traveling Through Space ……………………………………….. 28 Schenker: Interruption, Form, and Allusion…………………… 31 Sharakans, Epithets, and Sufis…………………………………... 33 Friday afternoon Jazz: Chord-Scale Theory and Improvisation…………………… 35 American Composers Since 1945……………………………….. 37 Tonal Reconstructions ………………………………………….. 40 Exploring Voice Leading.……………………………………….. -

Y10 Music Revision

Tempo, Metre and Rhythm BPM The number of beats per minute in a piece of music. Largo Slowly and broadly Andante Fairly slow - at walking pace Moderato At moderate speed Allegro Fast Vivace Lively Presto Very quick Accelerando Gradually speeding up Rallentando Gradually slowing down Ritenuto Immediately slower Allargando Getting slower and broadening Rubato Literally 'robbed time', where rhythms are played freely for expressive effect Time Tells you how many beats are in a bar. Two numbers at the start signature of a piece of music. Syncopation Where the rhythms are played off the main beat. Cross A rhythm used simultaneously with another rhythm or rhythms - rhythm the rhythms do not fit together, Polyrhythm A rhythm which makes use of two or more different rhythms simultaneously. Triplets A triplet is a three-note pattern that fills the duration of a typical two-note pattern. Hemiola A hemiola is a rhythmic device that gives the impression of the music speeding up. Off beats An unaccented beat. Upbeat / The last beat of the measure/bar. anacrusis Swing In swing rhythm, the pulse is divided unequally (long/short) rhythms Walking A walking bass line generally consists of notes of equal duration bass and intensity (typically 1/4 notes) that create a feeling of forward motion. Dynamics and Articulation Dynamics Dynamics are used to show how loudly to play a piece of music. Articulation Articulation is used to show how a note should be played or sung - eg staccato or slur. Sostenuto Notes are sustained or held on. Crescendo Gradually getting louder Diminuendo Gradually getting quieter Fortissimo Very loud Forte Loud Mezzo Forte Moderately loud Mezzo Piano Moderately quiet Piano Quiet Pianissimo Very quiet Sforzando A note should be given sudden emphasis, similar to an accent. -

Wadsworth, Directional Tonality in Schumann's

Volume 18, Number 4, December 2012 Copyright © 2012 Society for Music Theory Directional Tonality in Schumann’s Early Works* Benjamin K. Wadsworth NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.12.18.4/mto.12.18.4.wadsworth.php KEYWORDS: Schumann, monotonality, directional tonality, tonal pairing, double tonic complex, topic, expressive genre ABSTRACT: Beginning and ending a work in the same key, thereby suggesting a hierarchical structure, is a hallmark of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century practice. Occasionally, however, early nineteenth-century works begin and end in different, but equally plausible keys (directional tonality), thereby associating two or more keys in decentralized complexes. Franz Schubert’s works are sometimes interpreted as central to this practice, especially those that extend third relationships to larger, often chromatic cycles. Robert Schumann’s early directional-tonal works, however, have received less analytical scrutiny. In them, pairings are instead diatonic between two keys, which usually relate as relative major and minor, thereby allowing Schumann to both oppose and link dichotomous emotional states. These diatonic pairings tend to be vulnerable to monotonal influences, with the play between dual-tonal (equally structural) and monotonal contexts central to the compositional discourse. In this article, I adapt Schenkerian theory (especially the modifications of Deborah Stein and Harald Krebs) to directional-tonal structures, enumerate different blendings of monotonal and directional-tonal states, and demonstrate structural play in both single- and multiple-movement contexts. Received July 2012 [1] In the “high tonal” style of 1700–1900, most works begin and end in the same key (“monotonality”), thereby suggesting a hierarchy of chords and tones directed towards that tonic. -

The Death and Resurrection of Function

THE DEATH AND RESURRECTION OF FUNCTION A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By John Gabriel Miller, B.A., M.C.M., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Doctoral Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. Gregory Proctor, Advisor Dr. Graeme Boone ________________________ Dr. Lora Gingerich Dobos Advisor Graduate Program in Music Copyright by John Gabriel Miller 2008 ABSTRACT Function is one of those words that everyone understands, yet everyone understands a little differently. Although the impact and pervasiveness of function in tonal theory today is undeniable, a single, unambiguous definition of the term has yet to be agreed upon. So many theorists—Daniel Harrison, Joel Lester, Eytan Agmon, Charles Smith, William Caplin, and Gregory Proctor, to name a few—have so many different nuanced understandings of function that it is nearly impossible for conversations on the subject to be completely understood by all parties. This is because function comprises at least four distinct aspects, which, when all called by the same name, function , create ambiguity, confusion, and contradiction. Part I of the dissertation first illuminates this ambiguity in the term function by giving a historical basis for four different aspects of function, three of which are traced to Riemann, and one of which is traced all the way back to Rameau. A solution to the problem of ambiguity is then proposed: the elimination of the term function . In place of function , four new terms—behavior , kinship , province , and quality —are invoked, each uniquely corresponding to one of the four aspects of function identified.