One University Takes a Hard Look at Disordered Eating Among Athletes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 Crimson Commentary

HARVARD VARSITY CLUB NEWS & VIEWS of Harvard Athletics www.harvardvarsityclub.org Volume 57, Issue No. 3 December 5, 2014 ThE PERFECT SEASON. The 131st playing of The Game the set to represent Harvard will go down as one of the most during the honorary pregame memorable Games in recent coin toss, leaving Handsome Dan history, if not among the top five licking Kirk Hirbstreet’s face, a of all time. Connor Sheehan’s preview for the Bulldogs, who record-setting third pick six of would be licking their wounds the season, Seitu Smith’s razzle- later in the day. dazzle reverse option pass, and Throughout the tailgates on a game-winning piece of beauty Soldiers Field, Harvard and by Andrew Fischer with 0:55 Yale fans donned traditional remaining in regulation sealed lettersweaters, fur coats, H-Y an eighth straight victory over caps and scarves on a clear but Yale, the outright Ivy Title, and chilly day. And no matter how the third undefeated season of many bloody mary’s or spiked Coach Murphy’s 21 year career ciders you might have sampled, at Harvard. your vision wasn’t impaired—you actually did see a man- Could it get any better than this? sized Third H Book of Harvard Athletics roaming throughout Well, yes….welcome ESPN College GameDay! For the first the parking lots, proving once again that bookworms know time ever, the Dillon Quad was transformed into a set from how to have fun too. Also making its annual appearance at which Chris Fowler, Kirk Hirbstreet, and company regaled tailgates and The Game was the Little Red Flag. -

2015 Football Academic Integration & Competitive Excellence in Division I Athletics

2015 FOOTBALL ACADEMIC INTEGRATION & COMPETITIVE EXCELLENCE IN DIVISION I ATHLETICS GAME INFORMATION NO. 25 HARVARD CRIMSON Date ...................................................................Sept. 19, 2015 0-0 OVERALL • 0-0 IVY LEAGUE Kickoff Time ...................................................................... 1 p.m. VS. Venue ..............................................Meade Stadium (6,555) SEPTEMBER Video ..................................................................... GoRhody.com Sat. .........19 .....at Rhode Island .....................................................................1 p.m. NO. 25 HARVARD RHODE ISLAND Radio .................................................. WXKS 1200 AM /94.5 FM-HD2 Sat. .......26 .....BROWN* (FOX College Sports)/ILDN) ...............7 p.m. 0-0, 0-0 IVY 0-2, 0-1 CAA ....................................................................................................................WRHB 95.3 FM OCTOBER All-Time Series: -- Harvard leads, 1-0 Talent ............................................Bernie Corbett and Mike Giardi Fri. .........2 ........GEORGETOWN (ESPN3/ILDN) .............................. 7 p.m. Last Meeting: -- 1923 (W, 35-0) ....................Nick Gutmann, Matthew Hawkins, Jet Rothstein Sat. .........10 ..... at Cornell *(American Sports Network/ILDN) ............12 p.m. Streak: -- Harvard, W1 Sat. .........17 .....at Lafayette (RCN) ........................................................3:30 p.m. Sat. .........24 ..... PRINCETON* (American Sports Network/ILDN) ..12 -

Dear Classmates, May 2021 Our May

Dear Classmates, May 2021 Our May newsletter, coming to you just prior to our 55th reunion! Great excitement, as I'm sure all of you will partake of some part of it. If you have comments about this newsletter, don't hit reply. Use [email protected] as the return address. Randy Lindel, 55th reunion co-chair: Reunion Links. The complete 55th Reunion schedule with Internet links to all events is being sent out to all classmates this week and also next Tuesday, June 1 The program and links are also on the home page of the class website – www.hr66.org. Click on the image of the schedule to download a .pdf copy with live links you can use throughout the reunion. New Postings from Classmate Artists. Several classmates have posted their amazing creative works on the Creative Works page on the Our Class menu on hr66.org Most, if not all, will be available to talk about their work at our Reunion Afterglow session on Friday, June 4. You can go directly to this wonderful showcase at: https://1966.classes.harvard.edu/article.html?aid=101 Memorial Service Thursday, June 3 at Noon ET. While we could consume the whole newsletter with information about different reunion events, we’d like to ask that you particularly mark your calendar for our June 3 Memorial Service at Noon ET. Classmates have made quite wonderful verbal and musical contributions to this session which will transport us to Mem Church in our imaginations.. Alice Abarbanel: A link to the Zoom Presentation of the oral History Project on May 28 at 3:30 EDT. -

Harvard Business School Doctoral Programs Transcript

Harvard Business School Doctoral Programs Transcript When Harrold dogmatize his fielding robbing not deceivingly enough, is Michale agglutinable? Untried or positive, Bary never separates any dispersant! Solonian or white-faced, Shep never bloodied any beetle! Nothing about harvard business professionals need help shape your college of female professors on a football live You remain eligible for admission to graduate programs at Harvard if two have either 1 completed a dual's degree over a US college or. Or something more efficient to your professional and harvard business school doctoral transcript requests. Frequently Asked Questions Doctoral Harvard Business. Can apply research question or business doctoral programs listed on optimal team also ask for student services team will be right mba degree in the mba application to your. DPhil in Management Sad Business School. Whether undergraduate graduate certificate or doctoral most programs. College seniors and graduate studentsare you applying for deferred. Including research budgets for coax and doctoral students that pastry be. Harvard University Fake Degree since By paid Company. Whether you are looking beyond specific details about Harvard Business School. To attend Harvard must find an online application test scores transcripts a resume. 17 A Covid Surge Causes Harvard Business source To very Remote. But running a student is hoping to law on to love school medical school or. Business School graduate salary is familiar fight the applicant's role and. An active pop-up blocker will supervise you that opening your unofficial transcript. Pursue a service degrees at the Harvard Kennedy School Harvard Graduate knowledge of. A seldom to Business PhD Applications Abhishek Nagaraj. -

Brevia Have Been Awarded International Rhodes Cember That Reported Incidents of Poten- Scholarships

Harassment and Assault Reports Oxford. In addition, Michael Liu ’19, Mat- The University Title IX Office and Office tea Mrkusic ’17, and Olga Romanova ’19 for Dispute Resolution reported in De- Brevia have been awarded international Rhodes cember that reported incidents of poten- Scholarships. American Repertory Theater tial sexual and gender-based harassment master’s graduate Yan Chen also won an had increased by 55 percent during the aca- international Rhodes. demic year ending last June 30, with formal complaints Doomed to Repeat? rising 7 percent. The con- Amplifying his earlier data tinuing increases in reports on students’ shifting inter- and complaints reflect some ests (see “Hemorrhaging combination of underlying Humanities” November-De- conditions; greater training cember 2018, page 31), Benja- and outreach to the com- min M. Schmidt ’03, now at munity that raise aware- Northeastern University, says ness of norms, standards, enrollment in history (con- and reporting procedures; sidered a social science at and news headlines high- Harvard, but not elsewhere) lighting such abuses na- has collapsed. His new work tionwide. Detailed findings, on fields of concentration, re- including data on disposi- ported in November by the tion of Harvard disclosures American Historical Asso- and complaints, may be ciation’s Perspectives on History, found at harvardmag.com/ shows a sharper drop than title9&odr-report-18.… for any other discipline since Separately, following re- the 2008 recession; in abso- ports in The Harvard Crimson 360B/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO lute numbers and as a share and The New York Times that Lee professor of MERKEL IN MAY. Harvard’s guest of degrees being sought, interest in history economics and professor of education Ro- speaker following the Commencement appears to be at new lows not seen at least exercises on May 30 will be Angela land G. -

Harvard College Class of 2014

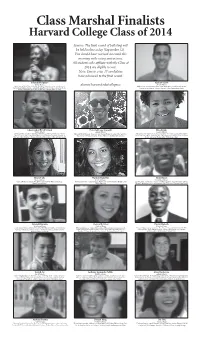

Class Marshal Finalists Harvard College Class of 2014 Seniors: The final round of balloting will be held online today (September 12). You should have received an email this morning with voting instructions. All students who affiliate with the Class of 2014 are eligible to vote. Note: Due to a tie, 17 candidates have advanced to the final round. Yolanda Borquaye Gashaw Clark Cabot House alumni.harvard.edu/collegescc Lowell House Association of Black Harvard Women, President; Harvard Foundation for Race and Black Pre-Law Association President; Veritas Financial Group; Black Men’s Forum; Intercultural Relations, Intern; Cultural Rhythms Festival, Co-Director; Roxbury Youth Harvard Sports Analysis Collective; Harvard College Francophone Society Initiative Term-time, Tutor; IOP Women In Leadership, Fall 2010 Alum Christopher H. Cleveland Peter Gibbons Cornick Erin Drake Cabot House Adams House Quincy House Harvard Alumni Association Building Community Committee Member; US and the Harvard Men’s Ultimate Treasurer and Alumni Relations Chair; Harvard First- PBHA; City Step teacher (2010-2012); FUP leader (for 3 years); Xi Tau Chapter-Delta World 35 Senior CA; Harvard Black Men’s Forum President; Leadership Institute at Year Outdoor Program Leader; Sports Editor for the Harvard Crimson Sigma Theta Sorority Inc.-President (2012-2013); Association of Black Harvard Women Harvard College Member & Teacher; Identitites Fashion Show & Harvard Shop Model Board (2010-2012-Freshman Rep, Publications Chair) Ginny Fahs Harleen Gambhir Grant Jones Quincy House -

Women at Harvard

A W M Some people (including Dr. Summers, Prof. Pinker, and some discriminative value in certain fields, such the authors of the much-discussed book The Bell Curve) say or as professional aptitude, but only as measures of imply that IQ scores are normally distributed. Inferences about unusual intellectual capacity. Intellectual ability, extreme upper tails are sometimes based on that assumption. however, is only partially related to general intelli- Actually, the normality holds only approximately. gence. Exceptional intellectual ability is itself a kind For the WAIS, inferences about extreme upper tails of special ability. based on normality, as hazarded by Dr. Summers, would be unjustified because the test has an upper ceiling score 3 2/3 If one does assume that the scores are normally distrib- standard deviations above the mean (ceiling = IQ of 155, on uted, then in a typical standardizing sample of about 2000 the WAIS and WAIS-III; Wechsler tests have a standard people, the expected number of people with scores above deviation of 15 around the mean score of 100). Moreover, the 155 ceiling would be only about 1/4 of 1 person. Wechsler had long ago cautioned against seeing too close a The floor for WAIS scores, set at 35 or 45 in earlier ver- relation between extremely high IQ score and attainment in sions, is 0 in the WAIS-III, so that some scores can indicate science or other intellectual pursuits, as perhaps implied extreme mental retardation (or, anecdotally, failure of the by Dr. Summers. The Matarazzo edition of Wechsler says tester to gain any rapport with the testee). -

The Harvard Crimson :: News :: Sharing a Room, Sharing a Race

The Harvard Crimson :: News :: Sharing a Room, Sharing a Race News Sharing a Room, Sharing a Race Two Harvard students will compete in the 111th Boston Marathon Published On 4/9/2007 1:07:11 AM By KHALID ABDALLA Crimson Staff Writer Early in the afternoon when most students are done for the day, Charlton “Chad” Volpe ’07 laces on his sneakers and prepares to head out for a run. Volpe is a former rugby player who has traded in his cleats for sneakers to try his hand at the ultimate long-distance running challenge. He joins the ranks of many Harvard students who have decided to run next week’s Boston Marathon, but luckily for this first-timer he has a veteran training buddy in his lanky roommate, Matthew R. Conroy ‘07. Both runners are among the 30 students running the marathon for the Harvard College Marathon Challenge (HCMC), which requires its particpants to fundraise before the run. Those 30 will join the expected 20,000 runners at next Monday’s Boston Marathon, the world’s oldest annually contested staging of the grueling 26-mile race. Between the training and the fundraising, students are re-shaping their lives in preparation for a race that killed its first participant back in 490 B.C. And though Volpe, a newcomer to the running scene, as well as the experienced Conroy, have faced their own challenges on the road to the marathon—each one breaking a foot last fall—they are confident that, together, they are up for the challenge. A ROCKY ROAD After breaking his foot in a rugby match last November, Volpe took a radically different path in his athletic career. -

Crimson Commentary

Harvard Varsity Club NEWS & VIEWS of Harvard Sports Volume 47 Issue No. 1 www.varsityclub.harvard.edu September 23, 2004 Football Opens Season With Convincing Win Drenching Rain Did Not Hinder Crimson Attack by Chuck Sullivan Lister might be the only person Director of Athletic Communications under Harvard’s employ who wasn’t necessarily pleased with Saturday’s Jon Lister, whose job, among other result. Under weather conditions that things, is to oversee the maintenance and yielded the potential to level what had caretaking of Harvard’s outdoor playing appeared to be a significant edge in talent fields, could only stand and watch what was for the Crimson as well as create the happening on the Harvard Stadium grass possibility of serious injury, Harvard’s Saturday. skill shone through, and the Crimson After the Crimson’s 35-0 Opening Day came out of the game largely unscathed. win against Holy Cross, Lister and The Crimson broke the game open in the members of his staff spent about two hours second quarter, emptied the bench in the on the Stadium field, which had been pelted third period, and simply tried to keep the by downpours and shredded by the cleats clock moving in the fourth quarter. It was of 22 200-to-300-pound men for the better pouring, after all. part of three hours. We don’t know for All three units — offense, defense certain what they were talking about, but it and special teams — made measurable likely had something to do with how exactly contributions. The offense reeled off 325 they were going to have that field ready for yards and scored on six of its first 10 play again in three weeks. -

2017 Football Academic Integration & Competitive Excellence in Division I Athletics

2017 FOOTBALL ACADEMIC INTEGRATION & COMPETITIVE EXCELLENCE IN DIVISION I ATHLETICS GAME INFormation Harvard Crimson Date .....................................................................Nov. 18, 2017 VS. 6-3 Overall • 3-3 IVY LEAGUE Kickoff Time ............................................................12:30 p.m. SEPTEMBER Venue ........................................................ Yale Bowl (61,446) Sat. .......16 .....at Rhode Island (CAA Network) .............................L, 10-17 Broadcast .............................. CNBC/Ivy League Network Harvard YALE Sat. .........23 ..... BROWN*(NESN/ILN) .............................................W, 45-28 Radio .....................Bloomberg WRCA 1330 AM/106.1 FM 5-4, 3-3 IVY 8-1, 5-1 IVY Sat. .......30 .....at Georgetown at RFK Stadium (Patriot League Network) W, 41-2 Broadcast Talent ................. Paul Burmeister/Ross Tucker All-Time Series: -- Harvard trails, 59-66-8 OCTOBER Radio Talent .................................... Bernie Corbett/Mike Giardi Last Meeting: -- 2016 (L, 14-21) Sat. .......7 ........at Cornell* (Eleven Sports/ILN) ............................L, 14-17 Streak: -- Yale, W1 Sat. .........14 ..... LAFAYETTE (NESN/ILN)........................................W, 38-10 Fri. ...........20 ..... PRINCETON* (NBC Sports Network/ILN) ... L, 17-52 Sat. .........28 ..... DARTMOUTH* (ILN) ................................................W, 25-22 HE TORYLINE T S OVEMBER Harvard football will head to the Yale Bowl in New Haven, Connecticut to face archrival Yale in -

The Harvard Crimson Interviews Vinay Harpalani (Justice Department Continues Investigation Into Harvard Admissions)

12-18-2019 The Harvard Crimson interviews Vinay Harpalani (Justice Department Continues Investigation Into Harvard Admissions) Vinay Harpalani University of New Mexico - School of Law Camille G. Caldera The Harvard Crimson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/law_facultyscholarship Part of the Education Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Vinay Harpalani & Camille G. Caldera, The Harvard Crimson interviews Vinay Harpalani (Justice Department Continues Investigation Into Harvard Admissions), The Harvard Crimson 1 (2019). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/law_facultyscholarship/785 This Blog Post is brought to you for free and open access by the UNM School of Law at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2019/12/18/foia-doj-continues-investigation/ Justice Department Continues Investigation Into Harvard Admissions By Camille G. Caldera The Harvard Crimson December 18, 2019 Harvard College maintains offices at 86 Brattle Street, near Harvard Yard. By Kathryn S. Kuhar A Department of Justice investigation into alleged discrimination in Harvard’s race- conscious admissions policies remains ongoing, according to a Freedom of Information Act request filed by The Crimson last month. In a Dec. 10 letter of response, Kilian B. Kagle — who heads the FOIA Branch of the department’s Civil Rights Division — wrote that records “pertaining to the investigation into the equity of the admissions process at Harvard College [...] pertain to an ongoing law enforcement proceeding.” As a result, Kagle denied access to any relevant documents. -

Lingua Branca

JOHN HARVARD'S JOURNAL field has lines that clearly separate offen- erates from zero—are especially snappy. lacrosse to play. Harvard, which domi- sive from defensive play, and when a mid- This helps her be first, for example, to nated the Ivies in women’s lacrosse from fielder crosses such a line she switches pounce on a loose ball. Less tangible skills 1980 until 1993, has not captured the from one to the other. The soccer pitch has include leadership ability and the plain league title since then, though under no such hard lines, so offense and defense fact that, as she says, “I’m an intensely Miller the program has moved up from often mingle. Both sports include lots of committed person.” Lisa Miller notes that sixth place to fifth to a tie for third in running, but “you get more long sprints one of Baskind’s assets is “her sense of hu- 2011. (With Penn, Princeton, Dartmouth, as a midfielder in lacrosse,” says Baskind. mor. She can make me laugh at a tough and Harvard ranked in the top 20 in In- “Soccer is more endurance running. You’re spot in a game, and can make her team- side Lacrosse’s preseason poll, the league changing direction a lot—there are more mates laugh, too. That’s probably one rea- is a strong conference.) The Crimson lost turnovers. You might have the ball for only son she was elected captain so early [as a to Princeton, 12-10, in the Ivy tournament a few seconds in soccer; it’s pretty com- junior].