Citizens and Sensors Eight Rules for Using Sensors to Promote Security and Quality of Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foss Maritime to Add Another Hybrid

DAILY COLLECTION OF MARITIME PRESS CLIPPINGS 2010 – 232 Number 232 *** COLLECTION OF MARITIME PRESS CLIPPINGS *** Friday 20-08-2010 News reports received from readers and Internet News articles copied from various news sites. SAIL **** SAIL 2010 **** IN The STAD AMSTERDAM leads the SAIL IN 2010 See also : http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AKH-yWeAw90 Distribution : daily 14600+ copies worldwide 20-08-2010 Page 1 DAILY COLLECTION OF MARITIME PRESS CLIPPINGS 2010 – 232 Your feedback is important to me so please drop me an email if you have any photos or articles that may be of interest to the maritime interested people at sea and ashore PLEASE SEND ALL PHOTOS / ARTICLES TO : [email protected] If you don't like to receive this bulletin anymore : To unsubscribe click here (English version) or visit the subscription page on our website. http://www.maasmondmaritime.com/uitschrijven.aspx?lan=en-US EVENTS, INCIDENTS & OPERATIONS VLIERODAM WIRE ROPES Ltd. wire ropes, chains, hooks, shackles, webbing slings, lifting beams, crane blocks, turnbuckles etc. Nijverheidsweg 21 3161 GJ RHOON The Netherlands Telephone: (+31)105018000 (+31) 105015440 (a.o.h.) Fax : (+31)105013843 Internet & E-mail www.vlierodam.nl [email protected] All photo’s : Piet Sinke (c) Yesterday morning the “SAIL AMSTERDAM 2010” started with the large “SAIL IN”, the SAIL 2010 is a five yearly event held in Amsterdam (The Netherlands), and is one of the largest sail events in the world. Distribution : daily 14600+ copies worldwide 20-08-2010 Page 2 DAILY COLLECTION OF MARITIME PRESS CLIPPINGS 2010 – 232 REPLICAS of a Russian frigate from 1703 and a merchant vessel sunk in 1745 leaded a fleet of some 50 tall ships into Amsterdam yesterday for what organisers say is Europe's biggest nautical event. -

Festivals Around the World © May/June 2017 Contents

Teacher’s Guide People, Places, and Cultures MAGAZINE ARTICLES The Timeless Fleet of Amsterdam . 10 Narrative Nonfiction 1130L Maslenitsa—The Pancake Festival . 14 . Expository Nonfiction 1140L Party in the Streets: Mombasa’s Carnival . .18 . Expository Nonfiction 1360L Abby Goes to La Feria . .22 . Narrative Nonfiction 810L Semana Santa: Guatemala’s Holy Week . 26. Expository Nonfiction . .1210L . Behind the Scenes of a Mardi Gras . 30 . Expository NonfictionAbby Goes 1260L to La Feria pg. 22 • The Mid-Autumn Festival pg. 38 Purim: The Joyous Jewish Holiday . 36 Expository NonfictionFESTIVALS 1050L AROUND THE WORLD The Mid-Autumn Festival . 38 Narrative Nonfiction 1350L Faces: Festivals around the World © May/June 2017 Contents Teacher’s Guide for Faces: OVERVIEW People, Places, and Cultures Festivals around the World In this magazine, readers will learn about Using This Guide . 2. different kinds of celebrations Skills and Standards Overview . 3. around the world. Abby Goes to La Feria pg. 22 • The Mid-Autumn Festival pg. 38 Faces: Festivals FESTIVALS AROUND THE WORLD around the Article Guides . 4 World includes information about the different reasons people celebrate, how people celebrate, Cross-Text Connections. 14. and some of the commonalities of festivals around the world. Mini-Unit . 15 Graphic Organizers . .18 . Appendix: Meeting State and National Standards . 21 ESSENTIAL QUESTION: How do festivals make places similar and different? 1 Faces: Festivals around the World © May/June 2017 Using This Guide We invite you to use this magazine as a flexible teaching tool, ideal for providing interdisciplinary instruction of social studies and science content as well as core literacy concepts . Find practical advice for teaching individual articles or use a mini-unit that helps your students make cross-text connections as they integrate ideas and information . -

Sail-World.Com News

sail-world.com -- 17 Nations at second Inter-Club Commodores' Forum Page 1 of 3 Sail-World.com News 2006 Inter-Club Commodore's Forum 17 Nations at second Inter-Club Commodores' Forum 2:31 PM Mon 29 May 2006 Last Saturday 27 May the flags of 17 nations were raised at the Royal Hong Kong Yacht club to mark the opening of the 2nd Inter-Club Commodores’ Forum. The Forum has attracted 82 participants, including Commodores, Flag Officers and General Managers from 27 clubs, hailing from 18 countries. The ICS was inaugurated last year by the Royal Vancouver Yacht Club. Subjects under discussion include ‘Strengthening International Ties’, ‘Sailing and its Role in the Community’ and ‘Sail Training and Youth Programmes’. On Sunday the Forum delegates raced for the first Commodores’ Cup – in Etchells, and in the worst downpour since, well, last weekend! The Royal Danish Yacht Club breezed home winners, and the photographer Commodore Inge Strompf-Jepsen, RHKYC - Guy Nowell © gave up because of poor visibility! Panel discu contin today 'Commodores, Flag Officers, flags, and lions at the opening of the 2nd Inter-Club Commodores’ and Forum' Guy Nowell © the Forum will close this eveni Commodores’ Cup 2006 - the wettest sailing in Hong Kong with since last weekend! - Guy Nowell © a Gala Dinner at the RHKYC. Sail-World Asia will be providing a full round-up of events, both formal and social, at the close of the Forum. Participating Clubs: Asia Aberdeen Boat Club - HK Hebe Haven Yacht Club - HK Kinabalu Yacht Club, Sabah, Malaysia Manila Yacht Club, Philippines -

HMAS Sydney in Action - the Ran’S First Big Test Bob Hetherington 36 “Barely a Year After the 1913 Fleet Review the RAN Found Itself Committed to WW1

Australian National Maritime Museum Volunteers’ Quarterly All Hands Issue 84 September 2013 Page Page 2 Page 3 EDITORIAL FAREWELL … Peter Wood This issue marks the celebration of the Readers would be aware that long-serving centenary of the arrival of the Royal Volunteers Manager, Peter Wood, has left Australian Navy’s first vessels in Sydney. the museum. All current volunteers have Virtually no-one will now remember that seen Peter at work at least in their event 100 years ago though it is being introductory interview and at guide recreated in October this year in very briefings. Peter’s great awareness of the grand fashion as the International Fleet entire volunteer force was a great strength Review (IFR). Imagine, a century ago, to the All Hands committee. island Australia was truly a maritime nation dependent solely on the sea to Your All Hands Committee has been in a bring here both people and the goods privileged position to work alongside him they needed to settle them. Then to producing many, many issues of this export our produce to markets across the magazine. oceans as well as protecting the sea lanes carrying these vessels to and fro. The magazine’s charter defines the official role that Peter played as: “Guide and advisor on policy matters”. But he did IFR 2013 much more. He suggested new ideas for adds to this naval centenary both a layer stories and their presentation; supported of visiting naval ships plus an array of most of them, but he was sometimes international tall ships in recognition of reserved about our ideas. -

Charging and Pricing in the Area of Inland Waterways

Charging and pricing in the area of inland waterways Practical guideline for realistic transport pricing Final report Client: European Commission - DG TREN ECORYS Transport (NL) METTLE (F) Rotterdam, 04 August 2005 ECORYS TRANSPORT Mettle P.O. Box 4175 3006 AD Rotterdam Watermanweg 44 3067 GG Rotterdam The Netherlands France T +31 10 453 88 00 T: +33 4 93 00 03 39 F +31 10 452 36 80 F: +33 4 93 00 15 70 E [email protected] W www.mettle.org W www.ecorys.com Registration no. 24316726 CB/TR10249r03 Table of contents Table of contents 5 Summary 9 1 Introduction 17 1.1 Background 17 1.2 Aim of the project 18 1.3 How to read this report 18 Part I: Theoretical framework 19 2 Charging for infrastructure use: marginal pricing issues 21 3 Infrastructure costs 25 3.1 General 25 3.2 Method of estimating marginal costs 25 4 Safety and accident costs 33 4.1 General 33 4.2 Cost drivers 33 4.3 Method of estimating marginal costs 33 5 Congestion costs 35 5.1 General 35 5.2 Cost drivers 35 5.3 Method of estimating marginal costs 35 6 Environmental costs 37 6.1 General 37 6.2 Cost drivers 37 6.3 Method of estimating marginal air pollution and noise costs 37 Part II: Marginal infrastructure costs 41 The case studies 41 7 Examples of applying the theoretical framework 43 8 Case study 1: Amsterdam-Rhine Channel 45 CB/TR10249r03 8.1 General information 45 8.2 Infrastructure costs 47 8.2.1 Cost drivers 47 8.2.2 Estimation of marginal costs 49 9 Case study 2: IJsselmeer route 55 9.1 General information 55 9.2 Infrastructure costs 58 9.2.1 Cost drivers 58 9.2.2 -

2019-Str-Grouppackages.Pdf

ABOUT STROMMA EVENTS FLEET LOOKOUT GROUP PACKAGES - EVENT SHIPS | PARTY SHIP | SALOON STEAMER | OPEN BOATS | PEDAL BOATS | EXTRAS STROMMA GROUP PACKAGES 2019 WE ARE STROMMA NETHERLANDS 2 ABOUT STROMMA EVENTS FLEET LOOKOUT GROUP PACKAGES - EVENT SHIPS | PARTY SHIP | CLASSIC BOAT | OPEN BOATS | PEDAL BOATS | EXTRAS SUSTAINABILITY We love Amsterdam and therefore work as sustainably as possible. Our fleet is clean and quiet, which is good for the environment and for the city. Sustainability is therefore also the key word in the collaboration with our suppliers and partners. Since 2012, we have been rewarded for this with the Golden Green Key award, the highest international quality mark for socially responsible entrepreneurship. At Stromma Netherlands – previously Canal Company – we know Amsterdam like no other. We know every canal, every bridge and every docking area. Sailing – that is what counts, whether it is by open boat, classic boat, event ship or pedal boat. Our wide range of activities allows 1.5 million guests annually to experience Amsterdam at its best: from the water! Our fleet has been sailing through the city for over thirty years and we have something FINLAND ÅLESUND for everyone. Exploring unfamiliar canals by classic boat, transferring from canal to canal GEIRANGER to combine transport with sightseeing or team-building on a pedal boat – all of these are NORWAY HELSINKI BERGEN possible with us. We are part of the international Stromma Group, active in the shipping OSLO SWEDEN STOCKHOLM industry and tourism for over 200 years already and with branches in twelve cities in five STAVANGER countries. Our brands Stromma, Canal Tours Amsterdam, Hop on-Hop off, Amsterdam GOTHENBURG DENMARK Excursions and A’DAM LOOKOUT are visible in the city. -

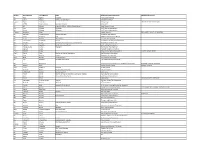

Registration List

Prefix First Name Last Name Title Affiliated Organization Affiliated Vessel Mr. Alex Agnew Publisher Professional Mariner Ms. Lori A. Aguiar Director of Operations Tall Ships America Captain Björn Ahlander Viking Kings DRAKEN HARALD HÅRFAGRE Mr PETER Alexandersson Managing Director Götheborg Mr Ali Alhosni Executive Officer , RNOV Shabab Oman II Royal Navy of Oman Mrs Ann Allaway Volunteer Sail Training International Mr Harry Allaway Volunteer Sail Training International Captain Nicholas Alley Mystic Seaport BRILLIANT, CHARLES W. MORGAN Mr eduardo almagro blanco General Manager Fundacion Nao Victoria Mr Asser Amdisen CEO Stiftelsen Georg Stages Minde Mr Jesper Amholt Chief Officer Training ship Danmark Mr Jørn Snorre Andersen Advisor Norwegian Sail Training Organisation Ms Jennifer Angel Vice President, Operations and Marketing Waterfront Development Mrs Pauline Appleby Conference Co-ordinator Sail Training International Mrs Renée-Claude Auclair President Distribution Teknolight inc Mr. Carlton Aylett Redpath Waterfront Festival Capt. Richard Bailey Oliver Hazard Perry Rhode Island OLIVER HAZARD PERRY Capt David Bank Director of Marine Operations Sea Education Association Mr Liam Barclay Captain Brigantine Incorporated Miss Brid Barrett Project Director The Rona Sailing Project Mr Hal Barstow Volunteer Sail Trainer Los Angeles Maritime Institute Ms. Anne Beaumont South Street Seaport Museum, NY Harbor Foundation PIONEER, LETTIE G. HOWARD Ms. Patrice Beck Mystic Whaler Cruises MYSTIC WHALER Miss Elvira Beetstra Manager Oosterschelde Mrs Nathalie Beloso Project Manager Events City of Antwerp Mr CHRISTIAN Bickert International VP STA France Mr Stuart Birnie Director of Marine Operations and Senior Captain Bermuda Sloop Foundation Mr Paul Bishop Head of Race Directorate Sail Training International Ms. Sarah Blank Viking Kings DRAKEN HARALD HÅRFAGRE Mrs Jeannette Blijdorp-Jonker Director Sail Den Helder/Sail Amsterdam Mr Herbert Boehm Dipl. -

Amsterdam Summit 12–14 November 2014 Contents

WORLD CITIES CULTURE FORUM Amsterdam Summit 12–14 November 2014 Contents Foreword 3 Welcome and Introduction 4 World Cities Culture Forum Vision and Values 5 World Cities Culture Summit Ethos 6 Programme 7 Participants 14 World Cities Culture Forum Management Team 42 Speakers 44 Governance and Operation 49 2 Foreword It is with great pleasure that I say to you: welcome I would like to thank the Mayor of London’s to Amsterdam! We are honored and delighted to Office and the World Cities Culture Forum for their welcome city leaders, senior representatives and work and cooperation with us throughout the experts from twenty-five cities for the Amsterdam organization of the summit. I would also like to World Cities Culture Summit 2014. thank all the partner organizations and cultural venues from Amsterdam for making it possible to The City of Amsterdam greatly values host this unique event. international cooperation, bilateral and multilateral. By sharing and exchanging knowledge and Whether this is your first experience of experiences, cities are taking their responsibility Amsterdam or you are a regular visitor, I truly hope and play a crucial role in setting the global agenda that you enjoy the occasion. May the Amsterdam for innovation and economic, urban and social World Cities Culture Summit 2014 serve as another development. The network of the World Cities important milestone for further cultural Culture Forum and its agenda for a sustainable cooperation between world cities. urban future through culture is unprecedented and Amsterdam is proud to be part of it. Yours sincerely, Arts and culture contribute in many different Eberhard van der Laan ways to the economic, urban and social Mayor of Amsterdam development of Amsterdam and the Metropolitan Area. -

CMMS Newsletter = January, 2016

The Connecticut Marine Model Society = CMMS Newsletter = January, 2016 DUFFISMS son and with input from sev - Member’s Gallery, so please We had 15 members attend the eral other members. Dave is take a look at the site and let January meeting, and two still uploading data for the him know what you think. guests (see next page, Sec - We are just beginning a retary’s Notes ). One of the new year and, as everyone guests found us on the knows, time flies. The an - web. Our hope is to attract nual joint clubs Northeast more folks through our Ship Model Show and Con - website. ference is just around the Which leads me to ap - corner this April, an event plaud the efforts of our you won't want to miss. webmaster, Dave Dinan , Keep building and above ably assisted by Ron Neil - all, have fun! Duff www.ctshipmodels.org Secretary’s Report, January 9, 2016 next calendar year. Those mem - bers who wish can mail their dues payment directly to Pete or bring them to the next meeting. A brief announcement was made to correct the faulty im - pression that our Newsletter was the creation of the club’s Secretary (namely, me). Sev - eral members have been com - plimenting me on our Newsletter, which is nice but completely undeserved. All the kudos belong to Ron Neilson who has done an outstanding Duff Griffith job of producing our newsletter James McGuffick and clearly deserves our thanks Duff Griffith called the meeting Neilson. Besides Dave Dinan serving and appreciation for his work. -

2015 IMCA AGM Minutes

MEETING International Moth Class Association – Annual General Meeting DATE Tuesday 13 January 2015 TIME 1800 hours VENUE Sorrento Sailing Couta Boat Club, Victoria, AUS AGENDA ITEM MINUTE 1 WELCOME AND APPOINTMENT OF NATIONAL DELEGATES Attendance Meeting opened at 1824hrs Scott Babbage AUS Martin Gravare SWE John Genders AUS Bruce McLeod AUS National Delegate appointments for the AGM: Stefano Rizzi ITA Byron White AUS Will Logan AUS Reece Tailby AUS USA – Matt Knowles Hiroki Goto JPN Chris Steele NZL GER – Nil Fabien Frosch SUI Masatomo Suzuki JPN GBR – Nil Philip Kaseman SUI Andrew Sim AUS AUS – Emma Spiers Rayshele Martin AUS Alan Goddard AUS ITA – Stefano Rizzi Phil Kurts AUS Phil Mail AUS NED – Nil Les Thorpe AUS Sam England AUS FRA – Nil Mike O’Shea AUS David French AUS SWE – Martin Gravare Rosemary Collins Warren Sare AUS JPN – Hiroki Goto AUS Richard Jackson AUS SUI – Adriano Petrino Adriano Petrino SUI Simon Hiscocks GBR AUT – Nil Mark Robinson AUS ESP – Nil Matt Knowles USA NZL - Nil Anothony Kotoun USA Emma Spiers AUS 2 MINUTES OF LAST MEETING To approve the minutes of the AGM held in The minutes from the 2014 AGM were accepted. Proposed: Matt 2014. Knowles. Seconded: Scott Babbage. 3 PRESIDENT’S REPORT To receive a report from IMCA President Scott Second Moth World Championships within a 6-month period and again a _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ IMCA Meeting Minutes 20 July 2014 Babbage record number of competitors in attendance. Next championships will be in Hayama, Japan in May 2016. 4 TREASURER’S REPORT To receive a report from IMCA Treasurer See report attached. -

Sea History Index Issues 1-164

SEA HISTORY INDEX ISSUES 1-164 Page numbers in italics refer to illustrations Numbers 9/11 terrorist attacks, 99:2, 99:12–13, 99:34, 102:6, 103:5 “The 38th Voyagers: Sailing a 19th-Century Whaler in the 21st Century,” 148:34–35 40+ Fishing Boat Association, 100:42 “100 Years of Shipping through the Isthmus of Panama,” 148:12–16 “100th Anniversary to Be Observed Aboard Delta Queen,” 53:36 “103 and Still Steaming!” 20:15 “1934: A New Deal for Artists,” 128:22–25 “1987 Mystic International,” 46:26–28 “1992—Year of the Ship,” 60:9 A A. B. Johnson (four-masted schooner), 12:14 A. D. Huff (Canadian freighter), 26:3 A. F. Coats, 38:47 A. J. Fuller (American Downeaster), 71:12, 72:22, 81:42, 82:6, 155:21 A. J. McAllister (tugboat), 25:28 A. J. Meerwald (fishing/oyster schooner), 70:39, 70:39, 76:36, 77:41, 92:12, 92:13, 92:14 A. S. Parker (schooner), 77:28–29, 77:29–30 A. Sewall & Co., 145:4 A. T. Gifford (schooner), 123:19–20 “…A Very Pleasant Place to Build a Towne On,” 37:47 Aalund, Suzy (artist), 21:38 Aase, Sigurd, 157:23 Abandoned Shipwreck Act of 1987, 39:7, 41:4, 42:4, 46:44, 51:6–7, 52:8–9, 56:34–35, 68:14, 68:16, 69:4, 82:38, 153:18 Abbass, D. K. (Kathy), 55:4, 63:8, 91:5 Abbott, Amy, 49:30 Abbott, Lemuel Francis (artist), 110:0 ABCD cruisers, 103:10 Abel, Christina “Sailors’ Snug Harbor,” 125:22–25 Abel Tasman (ex-Bonaire) (former barquentine), 3:4, 3:5, 3:5, 11:7, 12:28, 45:34, 83:53 Abele, Mannert, 117:41 Aberdeen, SS (steamship), 158:30, 158:30, 158:32 Aberdeen Maritime Museum, 33:32 Abnaki (tugboat), 37:4 Abner Coburn, 123:30 “Aboard -

Sail Den Helder 2023

YOUNG PEOPLE INVOLVEMENT, SUPPORT OF THE TRAINEE PROGRAM SAIL DEN HELDER 2023 BIDBOOK SAIL DEN HELDER 1 SAIL DEN HELDER 2023 CONTENT Preface by Chairman Sail Den Helder 2023 Foundation ............................................................................ 5 Letter of recommendation by Mayor of Den Helder ............................................................................... 7 SAIL and Den Helder, a longstanding successful history ............................................................................ 9 Young people involvement, support of the trainee program ........................................................................ 13 Den Helder: the perfect start or stopover port for an STI race in NW-Europe ........................................................... 15 Map and lay-out SAIL Den Helder including naval facilities and port ................................................................. 16 In-port facilities, infrastructure and arrangements ................................................................................ 17 Preliminary outline program SAIL Den Helder 2023 ............................................................................... 20 Marketing and Public Relations ................................................................................................ 23 Corporate hospitality ......................................................................................................... 25 Event funding ..............................................................................................................