Hardbound Title Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Newsletter

Summer Newsletter www.juicenewtonfanclub.com Hello JNFC Members, I am so glad that this has been a good year for so many of you. Let me say, "WELCOME!" to all of the new members!! This edition of the JNFC Summer Newsletter is full of information about Juice that is sure to get all members excited. I wish everyone, a very happy and fun and most of all safe summer. Sweet, Sweet Juice The year was 1977. Two very talented songwriters collaborated on a song about a someone who had to be set right by their significant every day in order for things to be right. The song was a big hit for the popular brother and sister duo The Carpenters. The song writers were Otha Young and Juice Newton and the song was "Sweet, Sweet Smile." Many people have asked and wondered why Juice never recorded this song herself. They need not wonder any longer. Juice has recorded this classic song on her new compilation "The Ultimate Hits Collection." Juice has recorded a modern rendition of this song. Juice peforms a different tempo and this of course differs from the version that The Carpenters recorded. Juice gave the song a new personality. This CD is available on iTUNES and Amazon.com and other fine retail websites. GET YOURS TODAY!! 1 The Ultimate Hits Collection Tracks Angel of The Morning 1998 Version Love's Been A Little Bit Hard On Me 1998 Version Break It To Me Gently 1998 Version When I Get Over You This Old Flame 1998 Version The Trouble with Angels Hurt Original Version Ride 'em Cowboy 1998 Version Red Blooded American Girl Queen of Hearts 1998 Version The Sweetest Thing (I've Ever Known) 1998 Version Nighttime Without You Ask Lucinda Love Hurts Tell Her No Original Version Heart of The Night Original Version Crazy Little Thing Called Love Funny How Time Slips Away (Duet with Willie Nelson) A Little Love Original Version Sweet, Sweet Smile BRAND NEW RECORDING!!! The mix of newer renditions of some of Juice's classics along with the originals of other tracks makes this a CD that is sure to be entertaining and enjoyable. -

Year 1 Volume 1-2/2014

MICHAELA PRAISLER Editor Cultural Intertexts Year 1 Volume 1-2/2014 Casa Cărţii de Ştiinţă Cluj-Napoca, 2014 Cultural Intertexts!! Journal of Literature, Cultural Studies and Linguistics published under the aegis of: ∇ Faculty of Letters – Department of English ∇ Research Centre Interface Research of the Original and Translated Text. Cognitive and Communicative Dimensions of the Message ∇ Doctoral School of Socio-Humanities ! Editing Team Editor-in-Chief: Michaela PRAISLER Editorial Board Oana-Celia GHEORGHIU Mihaela IFRIM Andreea IONESCU Editorial Secretary Lidia NECULA ! ISSN 2393-0624 ISSN-L 2393-0624 © 2014 Casa Cărţii de Ştiinţă Editura Casa Cărţii de Ştiinţă Cluj-Napoca, Romania e-mail: [email protected] www.casacartii.ro SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Professor Elena CROITORU, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Professor Ioana MOHOR-IVAN, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Professor Floriana POPESCU, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Professor Mariana NEAGU, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Associate Professor Ruxanda BONTILĂ, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Associate Professor Steluţa STAN, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Associate Professor Gabriela Iuliana COLIPCĂ-CIOBANU, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Associate Professor Gabriela DIMA, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Associate Professor Daniela ŢUCHEL, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Associate Professor Petru IAMANDI, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Senior Lecturer Isabela MERILĂ, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Senior Lecturer Cătălina NECULAI, Coventry University, UK Senior Lecturer Nicoleta CINPOEŞ, University of Worcester, UK Postdoc researcher Cristina CHIFANE, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Postdoc researcher Alexandru PRAISLER, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi * The contributors are solely responsible for the scientific accuracy of their articles. -

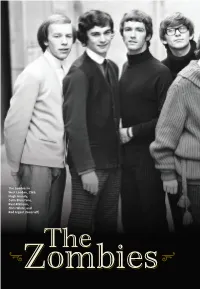

Hugh Grundy, Colin Blunstone, Paul Atkinson, Chris White, and Rod Argent (From Le )

The Zombies in West London, 1965: Hugh Grundy, Colin Blunstone, Paul Atkinson, Chris White, and Rod Argent (from le ) > The > 20494_RNRHF_Text_Rev1_70-95.pdfZombies 1 3/11/19 5:19 PM his year’s induction of the Zombies into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame is at once a celebration and a culmina- tion of one of the oddest and most convoluted careers in the history of popular music. While not the first band to have two smash hits right out of the box, they may be the only group who pro- ceeded to then fail miserably with their next ten sin- gles over a three-year period before finally achieving immortality with an album, Odessey [sic] and Oracle (1968) and a single, “Time of the Season,” that were released only after they had broken up. Even then, it would be a year after the album’s ini- tial release that, through the intercession of fate and Tthe idiosyncratic tastes of a handful of radio listeners in Boise, Idaho, “Time of the Season” would become a million-selling single and remain one of the most beloved staples of classic-rock radio to this day. Even more ironic was the fact that, despite that hit single, the album Odessey and Oracle was still met with indif- ference. Decades later, succeeding generations of crit- ics and an ever-growing cult fan base raised Odessey and Oracle to its status as one of the most cherished and revered albums of late 1960s British rock. As the album approached its fiftieth anniversary, four of the five original Zombies (guitarist Paul Atkinson passed away in 2004) went on tour, playing it in its entirety for sellout crowds throughout North America and the United Kingdom. -

Tell Her No Lies Design B.Indd

ACCLAIM FOR KELLY IRVIN “Kelly Irvin’s Through the Autumn Air is a poignant journey of friendship and sec- ond chances that will illustrate for readers that God blesses us with a true love for all seasons.” — amy clipston, bestselling author of ROOM ON THE PORCH SWING “A moving and compelling tale about the power of grace and forgiveness that reminds us how we become strongest in our most broken moments.” — LIBRARY JOURNAL for UPON A SPRING BREEZE “Irvin’s novel is an engaging story about despair, postnatal depression, God’s grace, and second chances.” — CBA CHRISTIAN MARKET for UPON A SPRING BREEZE “A warm- hearted novel that is more than a romance, with lovable characters, including two innocent children caught in the red tape of government and two people willing to risk breaking both the Englisch and Amish law to help in what- ever way they can. There are subplots that focus on the struggles of undocumented immigrants.” — RT BOOK REVIEWS, 4-star review of THE SADDLE MAKER’S SON “Irvin has given her audience a continuation of The Beekeeper’s Son with complicated young characters who must define themselves.” — RT BOOK REVIEWS, 4-star review of THE BISHOP’S SON “Once I started reading The Bishop’s Son, it was difficult for me to put it down! This story of struggle, faith, and hope will draw you in to the final page . I have read countless stories of Amish men or women doubting their faith. I have never read a storyline quite like this one though. It was narrated with such heart. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Blair's IPOD List

Blair’s IPOD list USAFA Class of 68 Music 1. Stranger on the Shore Ackerbilt 2. Boy From New York City Ad Libs 3. Magnificent Seven Theme Al Caiola 4. Alley Cat Al Hirt 5. Mary in the Morning Al Martino 6. Theme from Love Story Andy Williams 7. Moon River Andy Williams 8. Charade Andy Williams 9. We Gotta Get Out Of This Place Animals 10. House of the Rising Sun Animals 11. It's My Life Animals 12. Don’t Let Me be Misunderstood Animals 13. Teach Me Tiger April Stevens 14. Deep Purple April Stevens/N. Tempo 15. Respect Aretha Franklin 16. Think Aretha Franklin 17. Chain of Fools Aretha Franklin 18. Tighten Up Archie Bell & the Drells 19. You Better Move On Arthur Alexander 20. Sweet Soul Music Arthur Conley 21. Along Comes Mary Association 22. Never My Love Association 23. Cherish Association 24. Baja The Astronauts 25. Soul Finger Bar-Kays 26. I Know Barbara George 27. Baby I’m Yours Barbara Lewis 28. Eve of Destruction Barry McGuire 29. The Ballad of the Green Berets Barry Sadler 30. Little Deuce Coupe Beach Boys 31. God Only Knows Beach Boys 32. Wouldn't It Be Nice Beach Boys 33. That's Not Me Beach Boys 34. Be True to Your School Beach Boys 35. California Girls Beach Boys 36. Dance,Dance,Dance Beach Boys 37. Don't Worry Baby Beach Boys file:///E|/Webmaster/usafa/USAFAsonglist2.htm (1 of 15) [2/10/2007 2:12:55 PM] Blair’s IPOD list 38. Fun Fun Fun Beach Boys 39. -

Music Under the Stars Town Supervisor TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY

JULY JOHN VENDITTO Music Under the Stars Town Supervisor TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY JOHN J. BURNS ELLSWORTH W. ALLEN TAPPEN BEACH SYOSSET-WOODBURY JOHN J. BURNS TOWN PARK TOWN PARK Shore Road, Glenwood Landing COMMUNITY PARK TOWN PARK Merrick Road, Massapequa Motor Avenue, Farmingdale Jericho Turnpike, Woodbury Merrick Road, Massapequa 9 10 11 12 13 THAT 7070’S’s BAND THE ZOMBIES MAGICAL MUSIC “FROM CENTER FIELD NY’s Hottest Party Band MEET THE OF DISNEY TO CENTER STAGE” COLIN BLUNSTONE Around the World with Disney and ROD ARGENT JUMPERS featuring BERNIE WILLIAMS and his All-Star Band GLORIA GAYNOR “Time Of The Season” A Rockin’ & Swingin’ Big DEAN KARAHALIS “Tell Her No” and the Concert Pops “La Salsa En Mi” “I Will Survive” Band Orchestra “Just Because” “Never Can Say Goodbye” Orchestra CO-SPONSORED BY: CO-SPONSORED BY: CO-SPONSORED BY: CO-SPONSORED BY: SLOMIN’S SHIELD & DAVID LERNER ASSOCIATES, INC. & STEEL EQUITIES & BETHPAGE BUSINESS PARK WELLS FARGO & ROSLYN SAVINGS BANK-A DIVISION OF NEW SAHN WARD COSCHIGNANO AND KING KULLEN AMBER COURT ASSISTED LIVING YORK COMMUNITY BANK • MEMBER FDIC AND BAKER, PLLC. JOHN J. BURNS ELLSWORTH W. ALLEN SYOSSET-WOODBURY THEODORE ROOSEVELT JOHN J. BURNS TOWN PARK TOWN PARK COMMUNITY PARK MEMORIAL PARK & BEACH TOWN PARK Merrick Road, Massapequa Motor Avenue, Farmingdale Jericho Turnpike, Woodbury Larabee Avenue, Oyster Bay Merrick Road, Massapequa 16 17 18 19 20 Salute to America SATISFACTION Children’s Festival Showtime 7:30PM BROADWAY THE OSMOND The International & Safety Day TRAMPS LIKE US TONITE! BROTHERS Rolling Stones Show 1:00 PM - 4:00 PM A Bruce Springsteen JIMMY, JAY & MERRILL and Performing songs from Tribute SEE PAGE 10 FOR some of the greatest “One Bad Apple” ALMOST QUEEN FIREWORKS musicals of all time. -

Artist Title

O'Shuck Song List Ads Sept 2021 2021/09/20 Artist Title & The Mysterians 96 Tears (Hed) Planet Earth Bartender ´til Tuesday Voices Carry 10 CC I´m Not In Love The Things We Do For Love 10 Years Wasteland 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night More Than This These Are The Days Trouble Me 112 Dance With Me (Radio Version) Peaches And Cream (Radio Version) 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt 12 Stones We Are One 1910 Fruitgum Co. 1, 2, 3 Red Light 2 Live Crew Me So Horny We Want Some PUSSY (EXPLICIT) 2 Pac California Love (Original Version) Changes Dear Mama Until The End Of Time (Radio Version) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man (EXPLICIT) 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Be Like That (Radio Version) Here Without You It´s Not My Time Kryptonite Landing In London Let Me Go Live For Today Loser The Road I´m On When I´m Gone When You´re Young (Chart Buster) Sorted by Artist Page: 1 O'Shuck Song List Ads Sept 2021 2021/09/20 Artist Title When You´re Young (Pop Hits Monthly) 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 311 All Mixed Up Amber Down Love Song 38 Special Caught Up In You Hold On Loosely Rockin´ Into The Night Second Chance Teacher, Teacher Wild-eyed Southern Boys 3LW No More (Baby I´ma Do Right) (Radio Version) 3oh!3 Don´t Trust Me 3oh!3 & Kesha My First Kiss 4 Non Blondes What´s Up 42nd Street (Broadway Version) 42Nd Street We´re In The Money 5 Seconds Of Summer Amnesia 50 Cent If I Can´t In Da Club Just A Lil´ Bit P.I.M.P. -

Download Without the Beatles Here

A possible history of pop ... DAVID JOHNSTON To musicians and music-lovers, everywhere, and forever. A possible history of pop… DAVID JOHNSTON Copyright © 2020 David Johnston. All rights reserved. First published in 2020. ISBN 978-1-64999-623-7 This format is available for free, single-use digital transmission. Multiple copy prints, or publication for profit not authorised. Interested publishers can contact the author: [email protected] Book and cover design, layout, typesetting and editing by the author. Body type set in Adobe Garamond 11/15; headers Futura Extra Bold, Bold and Book Cover inspired by the covers of the Beatles’ first and last recorded LPs, Please Please Me and Abbey Road. CONTENTS PROLOGUE 1 I BEFORE THE BEATLES 1 GALAXIES OF STARS 5 2 POP BEGINNINGS 7 3 THE BIRTH OF ROCK’N’ROLL 9 4 NOT ONLY ROCK’N’ROLL 13 5 THE DEATH OF ROCK’N’ROLL AND THE RISE OF THE TEENAGE IDOLS 18 6 SKIFFLE – AND THE BRITISH TEENAGE IDOLS 20 7 SOME MARK TIME, OTHERS MAKE THEIR MARK 26 II WITHOUT THE BEATLES A hypothetical 8 SCOUSER STARTERS 37 9 SCOUSER STAYERS 48 10 MANCUNIANS AND BRUMMIES 64 11 THAMESBEAT 76 12 BACK IN THE USA 86 13 BLACK IN THE USA 103 14 FOLK ON THE MOVE 113 15 BLUES FROM THE DEEP SOUTH OF ENGLAND (& OTHER PARTS) 130 III AFTER THE BEATLES 16 FROM POP STARS TO ROCK GODS: A NEW REALITY 159 17 DERIVATIVES AND ALTERNATIVES 163 18 EX-BEATLES 190 19 NEXT BEATLES 195 20 THE NEVER-ENDING END 201 APPENDIX 210 SOURCES 212 SONGS AND OTHER MUSIC 216 INDEX 221 “We were just a band who made it very, very big. -

Et Cetera English Student Research

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Et Cetera English Student Research Spring 1998 et cetera Marshall University Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/english_etc Part of the Appalachian Studies Commons, Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Fiction Commons, Nonfiction Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Marshall University, "et cetera" (1998). Et Cetera. 15. https://mds.marshall.edu/english_etc/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English Student Research at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Et Cetera by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. O. e1eJ' c 'o E.1 9 \9 9 S\lri 1'1 Et Cetera Spring 1998 The Marshall University Literary Magazine Huntington, WV 1998 Et Cetera Staff Editor-in-chief Stacey Patterson Prose Editor Marsha Blevins Poetry Editor Tim Robinson Art Liason Tim Robinson Faculty Advisors Prof. Marie Manilla Prof. John Van Kirk Faculty Judges Prose: Dr. Christine Darrohn Poetry: Dr. Mary Moore Prizes First Place Prose Andy Charles The Tiet and Easter Sunday Second Place Prose Scott Morrison Of All the Sounds Third Place Prose Mark Fleshman The Legacy of Tom Martin First Place Poetry Deidre Conn in transit Second Place Poetry Matt Cooke Poet Third Place Poetry Alan Fairchild Premature Nightfall Cover Art Paula Rees Untitled Did anyone ask me? A letter from the editor anyway Well, I finally made it. This rookie has survived the year, but not without a great deal of help. -

Juice Newton Greatest Hits and More Cd

Juice newton greatest hits and more cd This item:Greatest Hits (And More) by Juice Newton Audio CD $ In Stock. Ships from The Best of Kim Carnes by Kim Carnes Audio CD $ Add-on Item. Juice Newton - Juice Newton - Greatest Hits [Cema/Atlantic] - Music. From the Heart: Greatest Hits by Bonnie Tyler Audio CD $ In Stock. Find a Juice Newton - Juice Newton's Greatest Hits (And More) first pressing or reissue. Complete your Juice Newton collection. Shop Vinyl and CDs. Find a Juice Newton - Greatest Hits first pressing or reissue. Complete your Juice Newton collection. Shop Vinyl and CDs. Find album reviews, stream songs, credits and award information for Juice Newton's Greatest Hits (And More) - Juice Newton on AllMusic - - One of a. Listen to songs from the album Juice Newton's Greatest Hits (And More), including "Angel of the Morning", "Heart of the Night", "Love's Been a. Title, Writer(s), Original album, Length. 1. Robbie Gillman / Juice Newton / Otha Young. Listen free to Juice Newton – Juice Newton's Greatest Hits (And More) (Angel of the Morning, Heart of the Do you know any background info about this album? Buy Juice Newton's Greatest Hits (And More) [CD] online at Best Buy. Preview songs and read reviews. Free shipping on thousands of items. Item in excellent condition, only played once. All items are posted within 3 working days. Please note we do not post on Saturdays and Sundays. All items are. Juice Newton's Greatest Hits by Juice Newton CD. About this product. More items related to this product. -

Juice Newton the Ultimate Hits Collection Mp3, Flac, Wma

Juice Newton The Ultimate Hits Collection mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: The Ultimate Hits Collection Country: US MP3 version RAR size: 1247 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1587 mb WMA version RAR size: 1333 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 481 Other Formats: AAC DMF VOX WAV MP4 MMF VQF Tracklist 1 Angel Of The Morning 4:15 2 Love's Been A Little Bit Hard On Me 3:10 3 Break It To Me Gently 4:04 4 When I Get Over You 3:49 5 This Old Flame 3:37 6 The Trouble With Angels 3:57 7 Hurt 3:45 8 Ride 'Em Cowboy 4:14 9 Red Blooded American Girl 5:02 10 Queen Of Hearts 3:27 11 The Sweetest Thing (I've Ever Known) 4:15 12 Nighttime Without You 2:36 13 Ask Lucinda 2:51 14 Love Hurts 4:04 15 Tell Her No 3:35 16 Heart Of The Night 4:10 17 Crazy Little Thing Called Love 2:45 18 Funny How Time Slips Away (Duet With Willie Nelson) 3:35 19 A Little Love 3:58 20 Sweet Sweet Smile 3:34 Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0 30206 19902 4 Matrix / Runout: 3020619902 3G Mastering SID Code: IFPI L239 Mould SID Code: IFPI 4152 Related Music albums to The Ultimate Hits Collection by Juice Newton Various - Open Country Queen - Cosita Tonta Llamada Amor = Crazy Little Thing Called Love Willie Nelson - All Time Greatest Hits Vol. 1 Juice Newton - Juice Juice Newton - The Sweetest Thing (I've Ever Known)/Ride'Em Cowboy Queen + Paul Rodgers - Crazy Little Thing Called Love (Rotterdam 7 October 2008) Juice Newton - Greatest Hits Jay Holman - Love Is A Sweet Thing / All American Music Various - Love Is ..