UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE the Dystopian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

Index Academy Awards (Oscars), 34, 57, Antares , 2 1 8 98, 103, 167, 184 Antonioni, Michelangelo, 80–90, Actors ’ Studio, 5 7 92–93, 118, 159, 170, 188, 193, Adaptation, 1, 3, 23–24, 69–70, 243, 255 98–100, 111, 121, 125, 145, 169, Ariel , 158–160 171, 178–179, 182, 184, 197–199, Aristotle, 2 4 , 80 201–204, 206, 273 Armstrong, Gillian, 121, 124, 129 A denauer, Konrad, 1 3 4 , 137 Armstrong, Louis, 180 A lbee, Edward, 113 L ’ Atalante, 63 Alexandra, 176 Atget, Eugène, 64 Aliyev, Arif, 175 Auteurism , 6 7 , 118, 142, 145, 147, All About Anna , 2 18 149, 175, 187, 195, 269 All My Sons , 52 Avant-gardism, 82 Amidei, Sergio, 36 L ’ A vventura ( The Adventure), 80–90, Anatomy of Hell, 2 18 243, 255, 270, 272, 274 And Life Goes On . , 186, 238 Anderson, Lindsay, 58 Baba, Masuru, 145 Andersson,COPYRIGHTED Karl, 27 Bach, MATERIAL Johann Sebastian, 92 Anne Pedersdotter , 2 3 , 25 Bagheri, Abdolhossein, 195 Ansah, Kwaw, 157 Baise-moi, 2 18 Film Analysis: A Casebook, First Edition. Bert Cardullo. © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 284 Index Bal Poussière , 157 Bodrov, Sergei Jr., 184 Balabanov, Aleksei, 176, 184 Bolshevism, 5 The Ballad of Narayama , 147, Boogie , 234 149–150 Braine, John, 69–70 Ballad of a Soldier , 174, 183–184 Bram Stoker ’ s Dracula , 1 Bancroft, Anne, 114 Brando, Marlon, 5 4 , 56–57, 59 Banks, Russell, 197–198, 201–204, Brandt, Willy, 137 206 BRD Trilogy (Fassbinder), see FRG Barbarosa, 129 Trilogy Barker, Philip, 207 Breaker Morant, 120, 129 Barrett, Ray, 128 Breathless , 60, 62, 67 Battle -

Beneath the Surface *Animals and Their Digs Conversation Group

FOR ADULTS FOR ADULTS FOR ADULTS August 2013 • Northport-East Northport Public Library • August 2013 Northport Arts Coalition Northport High School Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Courtyard Concert EMERGENCY Volunteer Fair presents Jazz for a Yearbooks Wanted GALLERY EXHIBIT 1 Registration begins for 2 3 Friday, September 27 Children’s Programs The Library has an archive of yearbooks available Northport Gallery: from August 12-24 Summer Evening 4:00-7:00 p.m. Friday Movies for Adults Hurricane Preparedness for viewing. There are a few years that are not represent- *Teen Book Swap Volunteers *Kaplan SAT/ACT Combo Test (N) Wednesday, August 14, 7:00 p.m. Northport Library “Automobiles in Water” by George Ellis Registration begins for Health ed and some books have been damaged over the years. (EN) 10:45 am (N) 9:30 am The Northport Arts Coalition, and Safety Northport artist George Ellis specializes Insurance Counseling on 8/13 Have you wanted to share your time If you have a NHS yearbook that you would like to 42 Admission in cooperation with the Library, is in watercolor paintings of classic cars with an Look for the Library table Book Swap (EN) 11 am (EN) Thursday, August 15, 7:00 p.m. and talents as a volunteer but don’t know where donate to the Library, where it will be held in posterity, (EN) Friday, August 2, 1:30 p.m. (EN) Friday, August 16, 1:30 p.m. Shake, Rattle, and Read Saturday Afternoon proud to present its 11th Annual Jazz for emphasis on sports cars of the 1950s and 1960s, In conjunction with the Suffolk County Office of to start? Visit the Library’s Volunteer Fair and speak our Reference Department would love to hear from you. -

Arrow Video Arrow Vi Arrow Video Arrow Video Arrow

ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO 1 ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO Music Composed and Performed by THE DRILLER KILLER Joseph Delia Reno … Jimmy Laine [Abel Ferrara] Editors Carol … Carolyn Marz Pamela … Baybi Day Orlando Gallini Dalton Briggs … Harry Schultz Bonnie Constant Landlord … Alan Wynroth Michael Constant [ ] Nun … Maria Helhoski Jimmy Laine Abel Ferrara Man in Church … James O’Hara Special Effects Carol’s Husband … Richard Howorth ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO Knife Victim … Louis Mascolo David Smith Attacker … Tommy Santora Director of Photography Derelicts Ken Kelsch Produced by Hallway … John Coulakis Rooftop … Lanny Taylor Navaron Films Bus Stop … Peter Yellen ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO Executive Producer Empire State … Steve Cox Street Corner … Stephen Singer Rochelle Weisberg Street Corner … Tom Constantine Screenplay Sidewalk and Street … Anthony Picciano Fire Escape … Bob De Frank N.G. St. John Roosters Directed by ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO Abel Ferrara Tony Coca-Cola (guitar) … Rhodney Montreal [D.A. Metrov] And Dedicated to the People of New York Ritchy (bass) … Dicky Bittner Steve (drums) … Steve Brown “The City of Hope” ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO 2 3 ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO CONTENTS 2 The Driller Killer Cast and Crew 7 All Around, In the City (2016) ARROW VIDEOby Michael Pattison ARROW VIDEO 16 Mulberry St. Crew 17 The Memory of a Reality (2016) by Brad Stevens ARROW26 About the VIDEORestoration ARROW VIDEO 4 5 ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ALL AROUND, IN THE CITY by Michael Pattison On 31 October 1977, horror struck the front page of the Village Voice. -

SFRA Newsletter 259/260

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 12-1-2002 SFRA ewN sletter 259/260 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 259/260 " (2002). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 76. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/76 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #2Sfl60 SepUlec.JOOJ Coeditors: Chrlis.line "alins Shelley Rodrliao Nonfiction Reviews: Ed "eNnliah. fiction Reviews: PhliUp Snyder I .....HIS ISSUE: The SFRAReview (ISSN 1068- 395X) is published six times a year Notes from the Editors by the Science Fiction Research Christine Mains 2 Association (SFRA) and distributed to SFRA members. Individual issues are not for sale. For information about SFRA Business the SFRA and its benefits, see the New Officers 2 description at the back of this issue. President's Message 2 For a membership application, con tact SFRA Treasurer Dave Mead or Business Meeting 4 get one from the SFRA website: Secretary's Report 1 <www.sfraorg>. 2002 Award Speeches 8 SUBMISSIONS The SFRAReview editors encourage Inverviews submissions, including essays, review John Gregory Betancourt 21 essays that cover several related texts, Michael Stanton 24 and interviews. Please send submis 30 sions or queries to both coeditors. -

Filmske Mutacije: X. Festival Nevidljivog Filma Nasilje + Utopija

FILMSKE MUTACIJE: X. FESTIVAL NEVIDLJIVOG FILMA NASILJE + UTOPIJA FILM MUTATIONS: X. FESTIVAL OF INVISIBLE CINEMA VIOLENCE + UTOPIA UTORAK | TUESDAY 24. 1. 2017. ART-KINO CROATIA, RIJEKA 18:00 Otvorenje | Opening: Jonathan Rosenbaum, Tanja Vrvilo, Dragan Rubeša Kraljevstvo | Royaume | Kingdom, Marc Hurtado, 1991. 8-mm digital, boja zvuk | colour sound, 22 min Ms. 45 (Anđeo osvete) | Ms. 45 (a.k.a. Angel of Vengeance), Abel Ferrara, 1981. 35-mm, boja zvuk | colour sound, 81 min 20:15 Stanica Shinjuku | 新宿ステイション | Shinjuku Station, Motoharu Jonouchi, 1974. 16-mm, c/b zvuk | b/w sound, 14 min Umjetnik u gladovanju | 断食芸人 Danjiki geinin | Artist of Fasting, Masao Adachi, 2015. DCP, boja zvuk | colour sound, 104 min SRIJEDA | WEDNESDAY 25. 1. 2017. ART-KINO CROATIA, RIJEKA 18:00 Aurora | Aurore, Marc Hurtado, 1988. 8-mm digital, boja zvuk | colour sound, 20 min Kradljivci tijela | Body Snatchers, Abel Ferrara, 1993. 35-mm, boja zvuk | colour sound, 87 min 20:00 Najava Gewaltopije | ゲバルトピア予告 Gewaltopia yokokuhen | Gewaltopia Trailer, Motoharu Jonouchi, Nihon University Cinema Club, 1969. 16-mm, c/b zvuk | b/w sound, 13 min Galaksija | 銀河系 Ginkakei | Galaxy, Masao Adachi, 1967. 35-mm digital, tintirani c/b zvuk | tinted b/w sound, 75 min ČETVRTAK | THURSDAY 26. 1. 2017. MSU, ZAGREB 18:00 Otvorenje | Opening: Marc Hurtado, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Tanja Vrvilo Saturn Drive Duplex, Marc Hurtado, 2011. digital, boja zvuk | colour sound, 6 min Plavetnilo | Bleu | Blue, Marc Hurtado, 1994. 8-mm 16-mm, boja zvuk | colour sound, 32 min + Poesis activa: Marc Hurtado Aurora | Aurore, Marc Hurtado, 1988. 8-mm digital, boja zvuk | colour sound, 20 min Kraljevstvo | Royaume | Kingdom, Marc Hurtado, 1991. -

April 2018 82

82 APRIL 2018 APRIL 2018 83 “ A bird-brained movie to cheer the hearts of the far right wing,” sneered Vincent Canby in the 25 July 1974 edition of The New York Times. The movie he was reviewing was Death Wish, a new crime thriller directed by Michael Winner, in which Winner’s frequent cohort, Charles Bronson, embarked on a vigilante crusade in New York, incited by the murder of his wife and rape of his daughter. And Canby wasn’t alone in his disdain. Variety called it “a poisonous incitement to do-it- yourself law enforcement”. Roger Ebert in the Chicago Sun-Times thought its message was “scary”. But Death Wish was unstoppable. In the US, the $3 million movie grossed $22 million and was followed by four sequels, two now infamous for their extreme sexual violence. The fnal one, 1994’s Death Wish V: The Face Of Death, was Bronson’s fnal big-screen role. Even without him, the series refused to die, as the fact there’s a new remake incoming attests. It has, however, taken time to arrive. In 2006, it was announced that Sylvester Stallone would star in and direct a new Death Wish; when he left the project, Joe Carnahan (The A-Team) took over. That version languished in development hell too, and is only now circling the roles of Benjamin and police making it to the screen, directed by Eli DEATHWISH (1974) chief Frank Ochoa. But time went on, Roth from Carnahan’s script and starring It could all have been very different. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents PART I. Introduction 5 A. Overview 5 B. Historical Background 6 PART II. The Study 16 A. Background 16 B. Independence 18 C. The Scope of the Monitoring 19 D. Methodology 23 1. Rationale and Definitions of Violence 23 2. The Monitoring Process 25 3. The Weekly Meetings 26 4. Criteria 27 E. Operating Premises and Stipulations 32 PART III. Findings in Broadcast Network Television 39 A. Prime Time Series 40 1. Programs with Frequent Issues 41 2. Programs with Occasional Issues 49 3. Interesting Violence Issues in Prime Time Series 54 4. Programs that Deal with Violence Well 58 B. Made for Television Movies and Mini-Series 61 1. Leading Examples of MOWs and Mini-Series that Raised Concerns 62 2. Other Titles Raising Concerns about Violence 67 3. Issues Raised by Made-for-Television Movies and Mini-Series 68 C. Theatrical Motion Pictures on Broadcast Network Television 71 1. Theatrical Films that Raise Concerns 74 2. Additional Theatrical Films that Raise Concerns 80 3. Issues Arising out of Theatrical Films on Television 81 D. On-Air Promotions, Previews, Recaps, Teasers and Advertisements 84 E. Children’s Television on the Broadcast Networks 94 PART IV. Findings in Other Television Media 102 A. Local Independent Television Programming and Syndication 104 B. Public Television 111 C. Cable Television 114 1. Home Box Office (HBO) 116 2. Showtime 119 3. The Disney Channel 123 4. Nickelodeon 124 5. Music Television (MTV) 125 6. TBS (The Atlanta Superstation) 126 7. The USA Network 129 8. Turner Network Television (TNT) 130 D. -

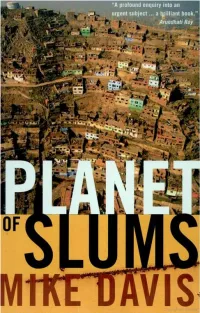

Mike Davis, Planet of Slums

- Planet of Slums • MIKE DAVIS VERSO London • New York formy dar/in) Raisin First published by Verso 2006 © Mike Davis 2006 All rights reserved The moral rights of the author have been asserted 357910 864 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F OEG USA: 180 Varick Street, New York, NY 10014 -4606 www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN 1-84467-022-8 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Typeset in Garamond by Andrea Stimpson Printed in the USA Slum, semi-slum, and superslum ... to this has come the evolution of cities. Patrick Geddes1 1 Quoted in Lev.isMumford, The City inHistory: Its Onj,ins,Its Transf ormations, and Its Prospects, New Yo rk 1961, p. 464. Contents 1. The Urban Climacteric 1 2. The Prevalence of Slums 20 3. The Treason of the State 50 4. Illusions of Self-Help 70 5. Haussmann in the Tropics 95 6. Slum Ecology 121 .7. SAPing the Third World 151 ·8. A Surplus Humanity? 174 Epilogue: Down Vietnam Street 199 Acknowledgments 207 Index 209 1 The U rhan Climacteric We live in the age of the city. The city is everything to us - it consumes us, and for that reason we glorify it. Onookome Okomel Sometime in the next year or two, a woman will give birth in the Lagos slum of Ajegunle, a young man will flee his viJlage in west Java for the bright lights of Jakarta, or a farmer will move his impoverished family into one of Lima's innumerable pueblosjovenes . -

Abel Ferrara

A FILM BY Abel Ferrara Ray Ruby's Paradise, a classy go go cabaret in downtown Manhattan, is a dream palace run by charismatic impresario Ray Ruby, with expert assistance from a bunch of long-time cronies, sidekicks and colourful hangers on, and featuring the most beautiful and talented girls imaginable. But all is not well in Paradise. Ray's facing imminent foreclosure. His dancers are threatening a strip-strike. Even his brother and financier wants to pull the plug. But the dreamer in Ray will never give in. He's bought a foolproof system to win the Lottery. One magic night he hits the jackpot. And loses the ticket... A classic screwball comedy in the madcap tradition of Frank Capra, Billy Wilder and Preston Sturges, from maverick auteur Ferrara. DIRECTOR’S NOTE “A long time ago, when 9 and 11 were just 2 odd numbers, I lived above a fire house on 18th and Broadway. Between the yin and yang of the great Barnes and Noble book store and the ultimate sports emporium, Paragon, around the corner from Warhol’s last studio, 3 floors above, overlooking Union Square. Our local bar was a gothic church made over into a rock and roll nightmare called The Limelite. The club was run by a gang of modern day pirates with Nicky D its patron saint. For whatever reason, the neighborhood became a haven for topless clubs. The names changed with the seasons but the core crews didn't. Decked out in tuxes and razor haircuts, they manned the velvet ropes that separated the outside from the in, 100%. -

Summer Newsletter

Summer Newsletter www.juicenewtonfanclub.com Hello JNFC Members, I am so glad that this has been a good year for so many of you. Let me say, "WELCOME!" to all of the new members!! This edition of the JNFC Summer Newsletter is full of information about Juice that is sure to get all members excited. I wish everyone, a very happy and fun and most of all safe summer. Sweet, Sweet Juice The year was 1977. Two very talented songwriters collaborated on a song about a someone who had to be set right by their significant every day in order for things to be right. The song was a big hit for the popular brother and sister duo The Carpenters. The song writers were Otha Young and Juice Newton and the song was "Sweet, Sweet Smile." Many people have asked and wondered why Juice never recorded this song herself. They need not wonder any longer. Juice has recorded this classic song on her new compilation "The Ultimate Hits Collection." Juice has recorded a modern rendition of this song. Juice peforms a different tempo and this of course differs from the version that The Carpenters recorded. Juice gave the song a new personality. This CD is available on iTUNES and Amazon.com and other fine retail websites. GET YOURS TODAY!! 1 The Ultimate Hits Collection Tracks Angel of The Morning 1998 Version Love's Been A Little Bit Hard On Me 1998 Version Break It To Me Gently 1998 Version When I Get Over You This Old Flame 1998 Version The Trouble with Angels Hurt Original Version Ride 'em Cowboy 1998 Version Red Blooded American Girl Queen of Hearts 1998 Version The Sweetest Thing (I've Ever Known) 1998 Version Nighttime Without You Ask Lucinda Love Hurts Tell Her No Original Version Heart of The Night Original Version Crazy Little Thing Called Love Funny How Time Slips Away (Duet with Willie Nelson) A Little Love Original Version Sweet, Sweet Smile BRAND NEW RECORDING!!! The mix of newer renditions of some of Juice's classics along with the originals of other tracks makes this a CD that is sure to be entertaining and enjoyable. -

Catalogue XV 116 Rare Works of Speculative Fiction

Catalogue XV 116 Rare Works Of Speculative Fiction About Catalogue XV Welcome to our 15th catalogue. It seems to be turning into an annual thing, given it was a year since our last catalogue. Well, we have 116 works of speculative fiction. Some real rarities in here, and some books that we’ve had before. There’s no real theme, beyond speculative fiction, so expect a wide range from early taproot texts to modern science fiction. Enjoy. About Us We are sellers of rare books specialising in speculative fiction. Our company was established in 2010 and we are based in Yorkshire in the UK. We are members of ILAB, the A.B.A. and the P.B.F.A. To Order You can order via telephone at +44(0) 7557 652 609, online at www.hyraxia.com, email us or click the links. All orders are shipped for free worldwide. Tracking will be provided for the more expensive items. You can return the books within 30 days of receipt for whatever reason as long as they’re in the same condition as upon receipt. Payment is required in advance except where a previous relationship has been established. Colleagues – the usual arrangement applies. Please bear in mind that by the time you’ve read this some of the books may have sold. All images belong to Hyraxia Books. You can use them, just ask us and we’ll give you a hi-res copy. Please mention this catalogue when ordering. • Toft Cottage, 1 Beverley Road, Hutton Cranswick, UK • +44 (0) 7557 652 609 • • [email protected] • www.hyraxia.com • Aldiss, Brian - The Helliconia Trilogy [comprising] Spring, Summer and Winter [7966] London, Jonathan Cape, 1982-1985. -

Journal for Critical Animal Studies

ISSN: 1948-352X Volume 10 Issue 3 2012 Journal for Critical Animal Studies Special issue Inquiries and Intersections: Queer Theory and Anti-Speciesist Praxis Guest Editor: Jennifer Grubbs 1 ISSN: 1948-352X Volume 10 Issue 3 2012 EDITORIAL BOARD GUEST EDITOR Jennifer Grubbs [email protected] ISSUE EDITOR Dr. Richard J White [email protected] EDITORIAL COLLECTIVE Dr. Matthew Cole [email protected] Vasile Stanescu [email protected] Dr. Susan Thomas [email protected] Dr. Richard Twine [email protected] Dr. Richard J White [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITORS Dr. Lindgren Johnson [email protected] Laura Shields [email protected] FILM REVIEW EDITORS Dr. Carol Glasser [email protected] Adam Weitzenfeld [email protected] EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD For more information about the JCAS Editorial Board, and a list of the members of the Editorial Advisory Board, please visit the Journal for Critical Animal Studies website: http://journal.hamline.edu/index.php/jcas/index 2 Journal for Critical Animal Studies, Volume 10, Issue 3, 2012 (ISSN1948-352X) JCAS Volume 10, Issue 3, 2012 EDITORIAL BOARD ............................................................................................................. 2 GUEST EDITORIAL .............................................................................................................. 4 ESSAYS From Beastly Perversions to the Zoological Closet: Animals, Nature, and Homosex Jovian Parry .............................................................................................................................