Non-Hepatic Hyperammonaemia: an Important, Potentially Reversible Cause of Encephalopathy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Picquestion of the Week:3/09/09

McKechnie Field - Spring Training Home of the Pirates PIC QUESTION OF THE WEEK: 3/09/09 Q: Why is rifaximin used in patients with pouchitis? A: Pouchitis is an inflammation of the internal pouch fashioned from small intestinal tissue during ileal pouch anal anastamosis (IPAA). This surgical procedure bypasses the large intestine and may be employed in patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease. A temporary ileostomy is placed to allow the pouch to heal without risk of infection. IPAA is considered preferable to an ostomy for patients suffering from inflammatory bowel diseases refractory to medical treatment. The pouch serves as a collection device for waste, but permits the patient to experience regular bowel movements. It is typical for patients with an internal pouch to experience more frequent (average 6 per day) and watery bowel movements. Pouchitis is the most common complication of IPAA and widely regarded as an idiopathic disease; however, colonization by fecal bacteria may be a contributing factor. The condition occurs most commonly in the first six months following reversal of the ileostomy. Although its frequency decreases after six months, nearly 50% of patients with an IPAA will eventually experience pouchitis. Presenting symptoms include diarrhea, increased frequency of bowel movements, bleeding, abdominal pain, and fever. It can result in dehydration and, in severe cases, hospitalization. Treatment of acute pouchitis generally consists of a two-week course of antibiotic therapy with metronidazole or ciprofloxacin. Approximately 10% of patients do not respond to initial treatment and develop chronic (> 4 weeks) pouchitis. A small number of clinical trials support the potential use of rifaximin for the treatment of refractory or recurrent pouchitis. -

Diagnosis and Management of Primary Biliary Cholangitis Ticle

REVIEW ArtICLE 1 see related editorial on page x Diagnosis and Management of Primary Biliary Cholangitis TICLE R Zobair M. Younossi, MD, MPH, FACG, AGAF, FAASLD1, David Bernstein, MD, FAASLD, FACG, AGAF, FACP2, Mitchell L. Shifman, MD3, Paul Kwo, MD4, W. Ray Kim, MD5, Kris V. Kowdley, MD6 and Ira M. Jacobson, MD7 Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) is a chronic, cholestatic, autoimmune disease with a variable progressive course. PBC can cause debilitating symptoms including fatigue and pruritus and, if left untreated, is associated with a high risk of cirrhosis and related complications, liver failure, and death. Recent changes to the PBC landscape include a REVIEW A name change, updated guidelines for diagnosis and treatment as well as new treatment options that have recently become available. Practicing clinicians face many unanswered questions when managing PBC. To assist these healthcare providers in managing patients with PBC, the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Institute for Clinical Research & Education, in collaboration with the Chronic Liver Disease Foundation (CLDF), organized a panel of experts to evaluate and summarize the most current and relevant peer-reviewed literature regarding PBC. This, combined with the extensive experience and clinical expertise of this expert panel, led to the formation of this clinical guidance on the diagnosis and management of PBC. Am J Gastroenterol https://doi.org/10.1038/s41395-018-0390-3 INTRODUCTION addition, diagnosis and treatment guidelines are changing and a Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) is a chronic, cholestatic, auto- number of guidelines have been updated [4, 5]. immune disease with a progressive course that may extend over Because of important changes in the PBC landscape, and a num- many decades. -

Inside Liver Disease

Inside autoimmune liver disease 40 Nursing made Incredibly Easy! January/February 2019 www.NursingMadeIncrediblyEasy.com Copyright © 2019 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved. 1.5 ANCC CONTACT HOURS An overactive immune system can target any body tissue and cause damage. In AILD, the liver and bile ducts are under attack. By Richard L. Pullen, Jr., EdD, MSN, RN, CMSRN, and Patricia Francis-Johnson, DNP, RN Autoimmune liver disease (AILD)—primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH)—is comprised of three distinct pathologic processes in which a person’s immune system doesn’t recognize certain hepatic and biliary structures as belonging to the body. The im- mune system becomes overactive and targets healthy tissue, leading to inflammation, cirrho- sis, and end-stage liver disease (ESLD). Some patients may require liver transplantation as a lifesaving measure. This article presents the pathophysiology, epidemiology, risk factors, signs and symptoms, treatment strategies, and nursing care of patients with AILD. Primary biliary cholangitis PBC is a progressive inflammatory autoimmune disease that’s manifested by a destruction of the small intrahepatic bile ducts. Pathophysiology Destruction of the bile ducts leads to cholestasis, which causes an impairment in the flow and retention of bile—a substance produced by the liver and stored in the gallbladder that flows through the bile ducts and into the small intes- tine to digest lipids. Bile is comprised of bile salts, cholesterol, and bilirubin—a waste product from damaged red blood cells that accumulates in the blood because of cholestasis in PBC. Approximately 95% of patients with PBC pos- sess the antimitochondrial antibody (AMA) and a PBC-specific antinuclear antibody (ANA) that has a MEGIJA / CANSTOCK rim-like staining pattern. -

Primary Biliary Cholangitis: 2018 Practice Guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases 1 2 3 4 5 Keith D

| PRACTICE GUIDANCE HEPATOLOGY, VOL. 0, NO. 0, 2018 Primary Biliary Cholangitis: 2018 Practice Guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases 1 2 3 4 5 Keith D. Lindor, Christopher L. Bowlus, James Boyer, Cynthia Levy, and Marlyn Mayo Intended for use by health care providers, this guid- Preamble ance identifies preferred approaches to the diagnostic This American Association for the Study of and therapeutic aspects of care for patients with PBC. Liver Diseases (AASLD) 2018 Practice Guidance As with clinical practice guidelines, it provides gen- on Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC) is an update eral guidance to optimize the care of the majority of of the PBC guidelines published in 2009. The 2018 patients and should not replace clinical judgment for updated guidance on PBC includes updates on etiol- a unique patient. ogy and diagnosis, role of imaging, clinical manifesta- The major changes from the last guideline to this tions, and treatment of PBC since 2009. The AASLD guidance include information about obeticholic acid 2018 PBC Guidance provides a data-supported (OCA) and the adaptation of the guidance format. approach to screening, diagnosis, and clinical man- agement of patients with PBC. It differs from more recent AASLD practice guidelines, which are sup- Etiology of Primary Biliary ported by systematic reviews and a multidisciplinary panel of experts that rates the quality (level) of the Cholangitis evidence and the strength of each recommendation Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC) is considered using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, an autoimmune disease because of its hallmark sero- Development, and Evaluation system. In contrast, this logic signature, antimitochondrial antibody (AMA), (1-4) guidance was developed by consensus of an expert and specific bile duct pathology. -

Hepatic and Pancreatic Disorders Brian A

CHAPTER 22 Hepatic and Pancreatic Disorders Brian A. Hemstreet, PharmD, BCPS LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY TERMS AND DEFINITIONS After completing this chapter, you should be able to Ascites — abnormal accumulation of fl uid in the abdominal cavity. This 1. Defi ne the following: is a common complication of cirrhosis. ● Hepatitis Cirrhosis — a chronic liver disease ● Cirrhosis that is a result of longstanding or repeated damage to the liver. Scar ● Ascites tissue replaces tissue resulting in ● Encephalopathy many complications related to loss of ● Jaundice normal liver function. Cirrhosis is often ● Esophageal varices referred to as end stage liver disease. ● Portal hypertension Hepatic encephalopathy ● Pancreatitis (HE) — dysfunction of the brain and nervous system that occurs in ● Malabsorption patients with cirrhosis. This disorder is ● Pseudocyst thought to be due to the presence of 2. Recall common causes and complications of chronic liver disease waste products in the blood stream, such as ammonia, that are normally 3. Review the role and mechanism of common drug treatments for cirrhosis detoxifi ed by the liver. 4. Review adverse effects and drug interactions for medications used in the treatment Hepatitis — hepatitis means of chronic liver disease infl ammation of the liver and may be caused by a variety of diseases, 5. Identify key patient counseling points for medications used to treat complications toxins, and drugs. Hepatitis may by PART of chronic liver disease acute or chronic and patients may 6. Describe the anatomy and normal physiology of the liver and pancreas exhibit symptoms, such as abdominal pain, jaundice, or nausea. Hepatitis 7 7. Recognize common medications used in the management of acute pancreatitis may also be severe enough to require 8. -

Mechanisms, Diagnosis and Management of Hepatic Encephalopathy Ravi Prakash and Kevin D

REVIEWS Mechanisms, diagnosis and management of hepatic encephalopathy Ravi Prakash and Kevin D. Mullen Abstract | Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a serious neuropsychiatric complication of both acute and chronic liver disease. Symptoms of HE can include confusion, disorientation and poor coordination. A general consensus exists that the synergistic effects of excess ammonia and inflammation cause astrocyte swelling and cerebral edema; however, the precise molecular mechanisms that lead to these morphological changes in the brain are unclear. Cerebral edema occurs to some degree in all patients with HE, regardless of its grade, and could underlie the pathogenesis of this disorder. The different grades of HE can be diagnosed by a number of investigations, including neuropsychometric tests (such as the psychometric hepatic encephalopathy score), brain imaging and clinical scales (such as the West Haven criteria). HE is best managed by excluding other possible causes of encephalopathy alongside identifying and the precipitating cause, and confirming the diagnosis by a positive response to empiric treatment. Empiric therapy for HE is largely based on the principle of reducing the production and absorption of ammonia in the gut through administration of pharmacological agents such as rifaximin and lactulose, which are approved by the FDA for the treatment of HE. Prakash, R. & Mullen, K. D. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 7, 515–525 (2010); published online 10 August 2010; doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2010.116 Introduction Continuing Medical Education online Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a serious neuro This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance psychiatric complication of both acute and chronic with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council liver disease.1 This disease encompasses a broad range for Continuing Medical Education through the joint sponsorship of Medscape, LLC and Nature Publishing Group. -

Rifaximin (Xifaxan®) PAGE: 1 of 5 REFERENCE NUMBER

MEDICAL NECESSITY GUIDELINE DEPARTMENT: Pharmacy DOCUMENT NAME: rifaximin (Xifaxan®) PAGE: 1 of 5 REFERENCE NUMBER: NH.PMN.47 EFFECTIVE DATE: 11/11 REPLACES DOCUMENT: RETIRED: REVIEWED: 11/11, 12/14, 08/16, 07/17 PRODUCT TYPE: All REVISED: 11/12, 11/13, 09/16 IMPORTANT REMINDER This Clinical Policy has been developed by appropriately experienced and licensed health care professionals based on a thorough review and consideration of generally accepted standards of medical practice, peer-reviewed medical literature, government agency/program approval status, and other indicia of medical necessity. The purpose of this Clinical Policy is to provide a guide to medical necessity. Benefit determinations should be based in all cases on the applicable contract provisions governing plan benefits (“Benefit Plan Contract”) and applicable state and federal requirements, as well as applicable plan-level administrative policies and procedures. To the extent there are any conflicts between this Clinical Policy and the Benefit Plan Contract provisions, the Benefit Plan Contract provisions will control. Clinical policies are intended to be reflective of current scientific research and clinical thinking. This Clinical Policy is not intended to dictate to providers how to practice medicine, nor does it constitute a contract or guarantee regarding results. Providers are expected to exercise professional medical judgment in providing the most appropriate care, and are solely responsible for the medical advice and treatment of members. Description: Xifaxan is an oral rifamycin antibiotic. It has clinical utility in the treatment of infections caused by various gram-positive and gram-negative aerobes and anaerobes. The drug has virtually no systemic absorption, so its use is generally limited to treating GI infections. -

Budd Chiari Syndrome- an Overview

IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences (IOSR-JDMS) e-ISSN: 2279-0853, p-ISSN: 2279-0861.Volume 19, Issue 4 Ser.1 (April. 2020), PP 57-61 www.iosrjournals.org Budd Chiari Syndrome- An Overview Deva Priya, Pearlsy Grace Rajan, Melina.I.Sahay, Damal Kandadai Sriram, Melvin George Abstract: Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) is a serious, rare but life-threatening condition of the liver and requires immediate and aggressive medical interventions. Patients with BCS often have predisposing multiple prothrombotic factors for development of the disease. The epidemiology of BCS in the West and Asian countries differs greatly due to the various epidemiological characteristics in each of these regions. Recent studies suggest that a step wise strategical treatment approach have proven to have an excellent 5-year survival rate. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting and percutaneous transhepatic balloon angioplasty are the effective options in patients with hepatic obstruction. Orthotopic liver transplantation will be invariably required for those patients who are unresponsive to revascularization and TIPS. Other medical interventions are aimed at controlling further development of ascites and reducing the extent of thrombi in the hepatic veins and IVC. This review seeks to summarize the salient aspects of this medical condition and the various presentations seen with it. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date of Submission: 20-03-2020 Date of Acceptance: 06-04-2020 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. Introduction CASE PRESENTATION We report a case of a 24-year-old female who presented with chief complaints of abdominal pain and discomfort for 1 week. She also had a history of fever of 1-week duration and abdominal distension for 2 weeks. -

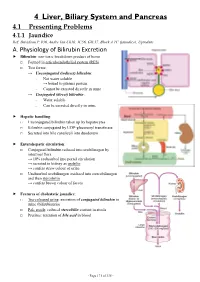

4 Liver, Biliary System and Pancreas 4.1 Presenting Problems 4.1.1 Jaundice Ref: Davidson P

4 Liver, Biliary System and Pancreas 4.1 Presenting Problems 4.1.1 Jaundice Ref: Davidson P. 936, Andre Tan Ch10, JC56, GIL17, Block A TC (jaundice), Uptodate A. Physiology of Bilirubin Excretion Bilirubin: non-toxic breakdown product of heme □ Formed in reticuloendothelial system (RES) □ Two forms: → Unconjugated (indirect) bilirubin: - Not water soluble → bound to plasma protein - Cannot be excreted directly in urine → Conjugated (direct) bilirubin: - Water soluble - Can be excreted directly in urine Hepatic handling: □ Unconjugated bilirubin taken up by hepatocytes □ Bilirubin conjugated by UDP-glucuronyl transferase □ Secreted into bile canaliculi into duodenum Enterohepatic circulation: □ Conjugated bilirubin reduced into urobilinogen by intestinal flora → 10% reabsorbed into portal circulation → secreted in kidney as urobilin → confers straw colour of urine □ Unabsorbed urobilinogen oxidized into stercobilinogen and then stercobilin → confers brown colour of faeces Features of cholestatic jaundice: □ Tea-coloured urine: excretion of conjugated bilirubin in urine (bilirubinuria) □ Pale stools: reduced stercobilin content in stools □ Pruritus: retention of bile acid in blood - Page 171 of 335 - B. Causes of Jaundice Pre-hepatic Hepatic Post-hepatic Suggestive - Lemon yellow jaundice - Yellow jaundice - Greenish jaundice features - Dark stools (↑stercobilin) - Normal stools - Pale stools - Normal urine - Tea-coloured urine - Tea-coloured urine - Pruritus ± scratch marks LFT - ↑unconj. bilirubin - ↑conj. bilirubin - ↑conj. Bilirubin -

Hepatic Encephalopathy, Hepatic Myelopathy, and Acquired Hepato‐Cerebral Degeneration Luis S

Hepatic Encephalopathy, Hepatic Myelopathy, and Acquired Hepato‐Cerebral Degeneration Luis S. Marsano, MD 2012 Hepatic Encephalopathy Definition & Pathogenesis • Reversible neuro‐psychiatric manifestation of severe liver dysfunction. – One‐year survival 40%. • Decreased hepatic clearance of ammonia derived from: – 1) kidney, – 2) urease activity of gastro‐intestinal bacteria, and – 3) deamination of glutamine in small bowel. • Increased Gut‐derived neuro‐mediators: – 1) benzodiazepine‐like substances, – 2) neurotoxic short‐ and medium‐chain fatty acids, – 3) phenols and, – 4) mercaptans. Types (by Cause) • Type A: Acute Liver Failure • Type B: Large Spontaneous or Post‐traumatic Portal‐ Systemic By‐pass (normal liver) – Uretero‐Sigmoid anastomosis. • Type C: Cirrhosis; Portal HTN or Shunt • Hepatic Myelopathy: Symmetrical demyelination of lateral corticospinal tracts Sub‐Categories of Cirrhotic Hepatic Encephalopathy • Minimal or Covert: – Detected only by psycho‐metric testing. – Impairs concentration and ability to drive. • Overt Episodic: – Clinically apparent (stages 1 to 4) – Usually precipitated after a triggering event. – May be spontaneous and recurrent • Chronic Persistent: – H.E. fluctuating from “mild” to “severe” – Usually without apparent trigger; – May be treatment dependent. – Very rare. West Haven Criteria Grade Symptoms 0 (minimal) • No detectable changes in behavior or personality1 • Euphoria or anxiety2 • Impaired performance of addition2 1 • Shortened attention span2 • Trivial lack of awareness2 • Minimal disorientation to time or place2 • Inappropriate behavior2 2 • Impaired performance of subtraction2 • Lethargy or apathy2 • Subtle personality change2 • Confusion2 3 • Gross disorientation2 • Somnolence to semistupor (may respond to verbal stimuli)2 4 • Coma (no response to verbal or noxious stimuli)2 HE = hepatic encephalopathy. 1. Mullen et al. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27(suppl 2):32-48. -

"Biloma". AJR Am J Roentgenol

Ying Monique Dieuvil M.D., John Malaty, M.D. Case Presentation, cont. Discussion • • Bilomas, extrabiliary collections of bile, are reported to occur • ERCP was unsuccessful to decompress the biloma. The A biloma is a rare abnormal accumulation of intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile caused by traumatic or spontaneous rupture biloma was subsequently drained by placement of CT-guided as a result of biliary surgery, endoscopic retrograde of the biliary tree. cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), laparoscopic percutaneous drains. • It is most commonly caused by surgery, percutaneous cholecystectomy, and trauma.1,2 • Biloma fluid culture/analysis demonstrated infection (E.coli transhepatic cholangiography (PTC), percutaneous • We describe here an uncommon cause of acute and Klebsiella ESBL) with WBC of 34 cumm. When patient transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD), and abdominal trauma • encephalopathy, an infected biloma status post transjugular was treated for biloma infection and acute cholangitis with The clinical symptoms of a biloma are nonspecific, and they can range from no symptoms to abdominal pain and cefepime, her encephalopathy completely resolved. With intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). distention, jaundice and fever; leukocytosis can also be adequate drainage, her hyperbilirubinemia also improved present back to her baseline level after her TIPS (total bilirubin of 3.7 • Term coined by Dr. Gould in 1979 mg/dL and direct bilirubin of 3.3 mg/dL). • Given rarity, only case reports of bilomas are present in the literature • Even rarer are cases of infected bilomas causing acute encephalopathy (no cases in PubMed) Figure • A 49 year old woman with a past medical history of alcoholic cirrhosis status post TIPS in 2012 with ongoing alcohol abuse, initially presented to the hospital with hematuria. -

Xifaxan (Rifaximin)

Market Applicability Market DC GA KY MD NJ NY WA Applicable X X X X X X NA Xifaxan (rifaximin) Override(s) Prior Authorization Quantity Limit Diagnosis Strength Approval Duration Hepatic Encephalopathy 550mg tablets 1 Year Travelers’ Diarrhea 200mg tablets 1 Time Only Irritable bowel syndrome with 550mg tablets Individual may have three 14 diarrhea (IBS-D) day courses of therapy within a 252 day time frame. Medication Strength Quantity Limits Xifaxan (rifaximin) 200mg tablets 9 tabs/30 days Xifaxan (rifaximin) 550mg tablets 42 tablets per fill; 3 fills per 36 weeks* *If Xifaxan (rifaximin) is being requested for prevention of overt hepatic encephalopathy recurrence, 2 tablets per day may be approved with no limits on number of fills. APPROVAL CRITERIA Requests for Xifaxan (rifaximin) may be approved for patients who meet the following criteria: I. For Travelers’ Diarrhea A. Individual has a diagnosis of travelers’ diarrhea (TD) ; AND B. Individual has already been started on Xifaxan (rifaximin) and needs to complete treatment; OR C. Individual has had a trial (medication samples/coupons/discount cards are excluded from consideration as a trial) and inadequate response or intolerance to one of the following agents (1. or 2. below) or has a contraindications to all of the following agents (both 1. and 2. below) (CDC, 2020): 1. Generic Fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin); 2. Generic Azithromycin. Note: Xifaxan (rifaximin) 200mg tablets are the only strength indicated for the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea. PAGE 1 of 3 08/15/2020 CRX-ALL-0586-20 This policy does not apply to health plans or member categories that do not have pharmacy benefits, nor does it apply to Medicare.