Ridesharing with Zimride at the University of Utah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rose Langhorst Senior Vice President and Treasurer Enterprise Holdings Inc

Rose Langhorst Senior Vice President and Treasurer Enterprise Holdings Inc. Rose Langhorst, Senior Vice President and Treasurer for Enterprise Holdings Inc., is a corporate officer and manages the global debt portfolio, as well as the company’s relationships with rating agencies, banks, investment bankers and investors. Enterprise Holdings operates – through an integrated global network of independent regional subsidiaries and franchises – the Enterprise Rent-A-Car, Alamo Rent A Car and National Car Rental brands, as well as more than 10,000 fully staffed neighborhood and airport locations in 100 countries and territories. Enterprise Holdings is the largest car rental company in the world, as measured by revenue and fleet. In addition, Enterprise Holdings is the most comprehensive service provider and only investment-grade company in the U.S. car rental industry. The company and its affiliate Enterprise Fleet Management together offer a total transportation solution, operating more than 2 million vehicles throughout the world. Combined, these businesses – accounting for $25.9 billion in revenue in fiscal year 2019 – include the Car Sales, Truck Rental, CarShare, Commute vanpooling, Zimride, Exotic Car Collection, Car Club (U.K.) and Flex-E-Rent (U.K.) services, all marketed under the Enterprise brand name. The annual revenues of Enterprise Holdings – one of America’s largest private companies – and Enterprise Fleet Management rank near the top of the global travel industry, exceeding many airlines and most cruise lines, hotels, tour operators, and online travel agencies. Langhorst began her career with Enterprise in 1988 as a Corporate Accountant at the company’s headquarters in St. Louis. In 1990, she was promoted to Business Management Analyst and in 1992 moved to Treasury, where she was responsible for day-to-day cash management and debt covenant compliance. -

Andrew C. Taylor Executive Chairman Enterprise Holdings Inc

Andrew C. Taylor Executive Chairman Enterprise Holdings Inc. Andrew Taylor, who became involved in the automotive business more than 50 years ago, currently serves as Executive Chairman of Enterprise Holdings Inc., the privately held business founded in 1957 by his father, Jack Taylor. Enterprise Holdings operates – through an integrated global network of independent regional subsidiaries and franchises – the Enterprise Rent-A-Car, Alamo Rent A Car and National Car Rental brands, as well as more than 10,000 fully staffed neighborhood and airport locations in 100 countries and territories. Enterprise Holdings is the largest car rental company in the world, as measured by revenue and fleet. In addition, Enterprise Holdings is the most comprehensive service provider and only investment-grade company in the U.S. car rental industry. The company and its affiliate Enterprise Fleet Management together offer a total transportation solution, operating more than 2 million vehicles throughout the world. Combined, these businesses – accounting for $25.9 billion in revenue in fiscal year 2019 – include the Car Sales, Truck Rental, CarShare, Commute vanpooling, Zimride, Exotic Car Collection, Subscribe with Enterprise, Car Club (U.K.) and Flex-E-Rent (U.K.) services, all marketed under the Enterprise brand name. The annual revenues of Enterprise Holdings – one of America’s largest private companies – and Enterprise Fleet Management rank near the top of the global travel industry, exceeding many airlines and most cruise lines, hotels, tour operators, and online travel agencies. Taylor joined Enterprise at the age of 16 in one of the original St. Louis offices. He began his career by washing cars during summer and holiday vacations and learning the business from the ground up. -

Zipcar and Zimride Join Forces on College Campuses

Innovation > Mobility & Transport > Zipcar and Zimride join forces on college campuses ZIPCAR AND ZIMRIDE JOIN FORCES ON COLLEGE CAMPUSES MOBILITY & TRANSPORT There are few things more exciting to us here at Springwise than seeing good ideas come together, and that’s exactly what we had occasion to spot earlier this month. Zipcar—the car-sharing innovator we’ve covered on numerous occasions already—just announced a partnership with Zimride —also no stranger to our pages—to bring an integrated ride-sharing system to college and university campuses. Debuting a few weeks ago at Stanford University, the integrated service combines Zipcar’s car-sharing program with Zimride’s Facebook-based carpool matching system to make it easier for college students, faculty and staff to seek, offer and share rides. Zipcar already operates car-sharing programs at more than 120 US colleges and universities. To share a ride, members reserving a car can now automatically post the date, time and destination of their trip to the Zimride campus community online. Zimride’s route-matching algorithm takes over from there, finding and notifying users looking for such a ride. Zimride members, meanwhile, can now find a local Zipcar to share through a customized campus Zimride website or Facebook application, making it possible for them to carpool even if they don’t own a car. Zipcar CEO Scott Griffith explains: “We chose to partner with Zimride because their innovative and scalable platform is a great foundation for building a national network of rides. Zipcar fills the car ownership gap for the Zimride model, since people most likely to ride-share are those that are least likely to own a car.” The two companies aim to roll out the integrated service to many more campuses in the coming months. -

A Proposal for Modernizing Labor Laws for Twenty-First-Century Work: the “Independent Worker”

DISCUSSION PAPER 2015-10 | DECEMBER 2015 A Proposal for Modernizing Labor Laws for Twenty-First-Century Work: The “Independent Worker” Seth D. Harris and Alan B. Krueger The Hamilton Project • Brookings 1 MISSION STATEMENT The Hamilton Project seeks to advance America’s promise of opportunity, prosperity, and growth. We believe that today’s increasingly competitive global economy demands public policy ideas commensurate with the challenges of the 21st Century. The Project’s economic strategy reflects a judgment that long-term prosperity is best achieved by fostering economic growth and broad participation in that growth, by enhancing individual economic security, and by embracing a role for effective government in making needed public investments. Our strategy calls for combining public investment, a secure social safety net, and fiscal discipline. In that framework, the Project puts forward innovative proposals from leading economic thinkers — based on credible evidence and experience, not ideology or doctrine — to introduce new and effective policy options into the national debate. The Project is named after Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s first Treasury Secretary, who laid the foundation for the modern American economy. Hamilton stood for sound fiscal policy, believed that broad-based opportunity for advancement would drive American economic growth, and recognized that “prudent aids and encouragements on the part of government” are necessary to enhance and guide market forces. The guiding principles of the Project remain consistent with these views. 2 Informing Students about Their College Options: A Proposal for Broadening the Expanding College Opportunities Project A Proposal for Modernizing Labor Laws for Twenty-First-Century Work: The “Independent Worker” Seth D. -

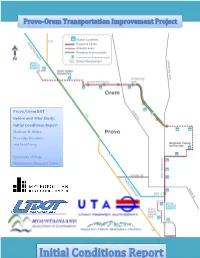

Provo/Orem BRT Before and After Study: Initial Conditions Report Matthew M

Provo/Orem BRT Before and After Study: Initial Conditions Report Matthew M. Miller, Mercedes Beaudoin, and Reid Ewing University of Utah, Metropolitan Research Center 2 of 142 Report No. UT‐17.XX PROVO-OREM TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENT PROJECT (TRIP) Prepared for: Utah Department of Transportation Research Division Submitted by: University of Utah, Metropolitan Research Center Authored by: Matthew M. Miller, Mercedes Beaudoin, and Reid Ewing Final Report June 2017 ______________________________________________________________________________ Provo/Orem BRT Before and After Study: Initial Conditions Report 3 of 142 DISCLAIMER The authors alone are responsible for the preparation and accuracy of the information, data, analysis, discussions, recommendations, and conclusions presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, endorsements, or policies of the Utah Department of Transportation or the U.S. Department of Transportation. The Utah Department of Transportation makes no representation or warranty of any kind, and assumes no liability therefore. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors acknowledge the Utah Department of Transportation (UDOT) for funding this research through the Utah Transportation Research Advisory Council (UTRAC). We also acknowledge the following individuals from UDOT for helping manage this research: Jeff Harris Eric Rasband Brent Schvanaveldt Jordan Backman Gracious thanks to our paid peer reviewers in the Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering, Brigham Young University: Dr. Grant G. Schultz, Ph.D., P.E., PTOE. Dr. Mitsuru Saito, Ph.D, P.E., F. ASCE, F. ITE While not authors, the efforts of the following people helped make this report possible. Data Collection Proof Reading/Edits Ethan Clark Ray Debbie Weaver Thomas Cushing Clint Simkins Jack Egan Debolina Banerjee Katherine A. -

Strategic Analysis of Carsharing Market in Europe

Sustainable and Innovative Personal Transport Solutions - Strategic Analysis of Carsharing Market in Europe M4FA-18 January 2010 Disclaimer Frost & Sullivan takes no responsibility for any incorrect information supplied to us by manufacturers or users. Quantitative market information is based primarily on interviews and therefore is subject to fluctuation. Frost & Sullivan research services are limited publications containing valuable market information provided to a select group of customers in response to orders. Our customers acknowledge when ordering that Frost & Sullivan research services are for our customers’ internal use and not for general publication or disclosure to third parties. No part of this research service may be given, lent, resold or disclosed to non-customers without written permission. Furthermore, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to: Frost & Sullivan 4 Grosvenor Gardens Sullivan House London SW1W 0DH United Kingdom © 2010 Frost & Sullivan. All rights reserved. This document contains highly confidential information and is the sole property of Frost & Sullivan. No part of it may be circulated, quoted, copied or otherwise reproduced without the written approval of Frost & Sullivan. M4FA-18 2 Certification We hereby certify that the views expressed in this research service accurately reflect our views based on primary and secondary research with industry participants, industry experts, end users, regulatory organisations, financial and investment community and other related sources. In addition to the above, our robust in-house forecast and benchmarking models along with the Frost & Sullivan Decision Support Databases have been instrumental in the completion and publishing of this research service. -

The Sharing Economy: Disrupting the Business and Legal Landscape

THE SHARING ECONOMY: DISRUPTING THE BUSINESS AND LEGAL LANDSCAPE Panel 402 NAPABA Annual Conference Saturday, November 5, 2016 9:15 a.m. 1. Program Description Tech companies are revolutionizing the economy by creating marketplaces that connect individuals who “share” their services with consumers who want those services. This “sharing economy” is changing the way Americans rent housing (Airbnb), commute (Lyft, Uber), and contract for personal services (Thumbtack, Taskrabbit). For every billion-dollar unicorn, there are hundreds more startups hoping to become the “next big thing,” and APAs play a prominent role in this tech boom. As sharing economy companies disrupt traditional businesses, however, they face increasing regulatory and litigation challenges. Should on-demand workers be classified as independent contractors or employees? Should older regulations (e.g., rental laws, taxi ordinances) be applied to new technologies? What consumer and privacy protections can users expect with individuals offering their own services? Join us for a lively panel discussion with in-house counsel and law firm attorneys from the tech sector. 2. Panelists Albert Giang Shareholder, Caldwell Leslie & Proctor, PC Albert Giang is a Shareholder at the litigation boutique Caldwell Leslie & Proctor. His practice focuses on technology companies and startups, from advising clients on cutting-edge regulatory issues to defending them in class actions and complex commercial disputes. He is the rare litigator with in-house counsel experience: he has served two secondments with the in-house legal department at Lyft, the groundbreaking peer-to-peer ridesharing company, where he advised on a broad range of regulatory, compliance, and litigation issues. Albert also specializes in appellate litigation, having represented clients in numerous cases in the United States Supreme Court, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, and California appellate courts. -

Randal Narike Executive Vice President, Global Mobility and Customer Experience Enterprise Holdings Inc

Randal Narike Executive Vice President, Global Mobility and Customer Experience Enterprise Holdings Inc. As Executive Vice President of Global Mobility and Customer Experience for Enterprise Holdings Inc., Randal Narike oversees several of the company’s mobility services and business lines. In addition, Narike directs the company’s global marketing, customer experience, customer excellence and data analytics teams. Enterprise Holdings operates – through an integrated global network of independent regional subsidiaries and franchises – the Enterprise Rent-A-Car, Alamo Rent A Car and National Car Rental brands, as well as more than 10,000 fully staffed neighborhood and airport locations in 100 countries and territories. Enterprise Holdings is the largest car rental company in the world, as measured by revenue and fleet. In addition, Enterprise Holdings is the most comprehensive service provider and only investment-grade company in the U.S. car rental industry. The company and its affiliate Enterprise Fleet Management together offer a total transportation solution, operating more than 2 million vehicles throughout the world. Combined, these businesses – accounting for $25.9 billion in revenue in fiscal year 2019 – include the Car Sales, Truck Rental, CarShare, Commute vanpooling, Zimride, Exotic Car Collection, Subscribe with Enterprise, Car Club (U.K.) and Flex-E-Rent (U.K.) services, all marketed under the Enterprise brand name. The annual revenues of Enterprise Holdings – one of America’s largest private companies – and Enterprise Fleet Management rank near the top of the global travel industry, exceeding many airlines and most cruise lines, hotels, tour operators, and online travel agencies. Narike began his career with Enterprise in 1985 after graduating with a Bachelor of Science in business management from California State University at Long Beach. -

Access Based Consumption in the Sharing Economy. Italy and the Mobility Sector

Dipartimento di Impresa e Management Cattedra di International Marketing ACCESS BASED CONSUMPTION IN THE SHARING ECONOMY. ITALY AND THE MOBILITY SECTOR. RELATORE Prof. Alberto Marcati CANDIDATA Margherita Scaglione Matr. 651401 CORRELATORE Prof. Giovanna Devetag ANNO ACCADEMICO 2013/2014 SUMMARY Introduction 3 Chapter 1. The access vs ownership dilemma 7 1.1 Ownership 7 1.2 Access 9 1.3 Access vs ownership. Some practical examples 12 3.1 The role of libraries 12 3.2 The music industry 14 1.4 The sharing trend 16 4.1 The sharing economy 19 1.5 Business implications of access and sharing 22 1.6 Summarizing 24 Chapter 2. Access, ownership and sharing solutions in the field of mobility 26 2.1 Mobility related issues 27 1.1 Benefits from reduced use of cars 29 2.2 Government recognition of sharing mobility practices 34 2.1 Europe – The MOMO Carsharing project 36 2.2 Italy – Libro Bianco sulla mobilità e i trasporti 38 2.3 Italy – Iniziativa Carsharing 39 2.3 Mobility sharing solutions 40 2 3.1 Carsharing 42 3.2 Car2go and Enjoy 47 3.3 Ridesharing 49 3.4 Uber 51 3.5 Carpooling 52 3.6 Blablacar 54 2.4 Likely evolutions in the car sector and in car ownership 55 Chapter 3. Focus on the access vs ownership dilemma in the mobility field. Is there a future for mobility sharing solutions in Italy? 56 3.1 Research objectives 56 3.2 Previous contributes 57 3.3 The questionnaire 61 3.4 Results analysis 64 Conclusion 78 References 82 3 Introduction The sharing economy is, today more than ever, a reality. -

Appendix F. Research Paper: Barriers to Trip Sharing in Emerging Mobility Technologies

Report on Colorado Senate Bill 19-239 APPENDIX F. RESEARCH PAPER: BARRIERS TO TRIP SHARING IN EMERGING MOBILITY TECHNOLOGIES Appendix F Research Paper: Barriers to Trip Sharing In Emerging Mobility Technologies Prepared for Colorado Department of Transportation Prepared by: October 2019 Barriers to Trip Sharing in Emerging Mobility Technologies October 2019 CONTENTS Page No. 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 1 1.1 Purpose of Report ....................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Definition of Trip Sharing ........................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Role of Emerging Technology in Shared Ride and Residential Delivery Industries........ 1 1.1.3 Impact of Trip Sharing Programs on Congestion ................................................ 2 2. TRANSPORTATION PROVIDER SHARED RIDE COMPATABILITY ................................. 2 2.1 TNC (Transportation Network Company) ............................................................ 2 2.2 Peer Car Share ........................................................................................... 2 2.3 Non-Peer Car Share ..................................................................................... 3 2.4 Taxi ........................................................................................................ 3 2.5 Car Rental ................................................................................................ 3 2.6 Residential -

Total Transportation Solutionsm

Total Transportation SolutionSM Business Rental Car Sales ™ We offer two great rental brands to meet the global transportation needs of business travelers Buy. Sell. Trade. Enterprise makes it easy. Exceptional customer service ® National Car Rental & Emerald Club Quality vehicle selection with over 7,000 low-mileage, 1-3 year-old cars, SUVs, trucks and vans Known for a fast, hassle-free rental process where customers can bypass the counter in more than 250 makes and models, all of which are inspected by an ASE-certified technician and choose their own car Competitive pricing for single or multiple vehicle purchases Enterprise Rent-A-Car Fair, transparent value for trade-ins with online valuation tool Known for affordable rates, neighborhood and airport convenience and award-winning For more information, visit enterprisecarsales.com customer service Mileage Reimbursement Alternative Lower cost per mile & improved bottom line Higher employee satisfaction Fleet Management Reduced liability expenses Consistent correct institution image With hands-on management and award-winning technology we show organizations how to identify opportunities for fleet savings. For more information, visit businessrentalprogram.com Reduce vehicle operating costs and increase safety Improve vehicle acquisition and resale processes with the infrastructure and experience of Enterprise Use real-time analytics and powerful technology to monitor, manage, and enhance your fleet program CarShare Dedicated, local account managers will identify new opportunities for savings -

UCTC PVS Project Reportfinal Shaheen

PEER-TO-PEER (P2P) CARSHARING: UNDERSTANDING EARLY MARKETS, SOCIAL DYNAMICS, AND BEHAVIORAL IMPACTS Susan Shaheen, Ph.D. Elliot Martin, Ph.D. Apaar Bansal University of California Transportation Center Final Report September 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. 3 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 10 2. BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................................ 13 2.1 THE SHARING ECONOMY ............................................................................................................................... 13 2.2 CARSHARING AND THE SHARING ECONOMY ......................................................................................... 14 2.3 FRACTIONAL OWNERSHIP ............................................................................................................................. 17 2.4 HYBRID P2P-ROUNDTRIP CARSHARING MODEL ................................................................................. 18 2.5 PREVIOUS RESEARCH ON P2P CARSHARING IMPACTS ..................................................................... 18 3. P2P CARSHARING OPERATOR SURVEY RESULTS ................................................................. 20 3.1 DEMOGRAPHICS OF P2P CARSHARING