History of Mascot Characters and Yuru-Chara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Let the Yuru-Chara Do the Job: Japan's Mascot Character Frenzy and Its

RECLAMO TURÍSTICO DE PERSONAJES DE FICCIÓN Y SU IMPACTO SOCIOECONÓMICO Mirai. Estudios Japoneses ISSN-e: 1988-2378 http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/MIRA.57115 Let the Yuru-Chara do the job: Japan’s Mascot Character Frenzy and its Socioeconomic Implications Eddy Y. L. Chang1 Abstract: In the land of Hello Kitty and Doraemon where cute characters and manga/cartoon characters enjoy immense popularity among people of all ages, a new breed of mascot characters known as Yuku-Chara have emerged to unforeseen popularity. These characters are not primarily intended for commercial success. Instead, they are “employed” to promote local culture and/or products to boost local economies. They have become so popular that an increasing number of people, organizations and businesses are turning to them to promote public relations, tourism, campaigns and local products. Keywords: Yuru-Chara; mascot; tourism; economy; (re)vitalization. [es] Dejad a los Yuru-Chara que hagan el trabajo: La fiebre de las mascotas japonesas y sus implicaciones socioeconómicas Resumen: En la tierra de Hello Kitty y Doraemon donde los personajes monos y de manga/anime disfrutan de una inmensa popularidad entre gente de todas las edades, una nueva raza de personajes mascota conocidos como Yuru-Chara han surgido con un imprevisto éxito. Estos personajes no se han creado con una intención principal de éxito comercial. En vez de ello, son “empleados” para promover la cultura local así como sus productos para promover las economías locales. Han llegado a ser tan populares que un número cada vez mayor de gente, organizaciones y negocios están acudiendo a ellos para promover sus relaciones públicas, el turismo, campañas específicas de concienciación o productos regionales. -

2008 Erik Axel Karlfeldt Memorial Open Round 3

2008 Erik Axel Karlfeldt Memorial Open Round 3 1. Montgomery Gentry performs this song on Dacin’ with Thunder, an album which claims to be “official music of the professional bull riders.” A cover of this song was performed by Chris Daughtry on the American Idol Season 5: Encores album. In the final episode of the third season of Supernatural, the Winchester brothers sing along to it while driving to New Harmony. Triumph the Insult Comic Dog once quoted its lyrics derisively to the band which introduced it to the world. It preceded “Never Say Goodbye” as a single from a 1987 album, and has been heard as the theme song to Deadliest Catch. Proclaiming that the singer is a “cowboy” who rides on a “steel horse,” FTP, name this song by Bon Jovi, which was meant to be part of a Western theme album. ANSWER: “Wanted Dead or Alive” 2. In its first season, this team was led by center Kamila Vodickova, the team’s first-ever draft pick, and Edna Campbell. This team is currently coached by Brian Agler, who replaced Hall of Famer Anne Donovan this past offseason. In the most recent draft they took Allie Quigley, and they had the first overall pick in the WNBA draft in both 2001 and 2002. They have made it out of the first round of the playoffs only once, in 2004, when they won the championship behind the play of Betty Lennox. Currently it features reigning MVP Lauren Jackson and point guard Sue Bird. FTP name this WNBA team that plays in Key Arena in the Pacific Northwest. -

Lista Ofrecida Por Mashe De Forobeta. Visita Mi Blog Como Agradecimiento :P Y Pon E Me Gusta En Forobeta!

Lista ofrecida por mashe de forobeta. Visita mi blog como agradecimiento :P Y pon e Me Gusta en Forobeta! http://mashet.com/ Seguime en Twitter si queres tambien y avisame que sos de Forobeta y voy a evalu ar si te sigo o no.. >>@mashet NO ABUSEN Y SIGAN LOS CONSEJOS DEL THREAD! http://blog.newsarama.com/2009/04/09/supernaturalcrimefightinghasanewname anditssolomonstone/ http://htmlgiant.com/?p=7408 http://mootools.net/blog/2009/04/01/anewnameformootools/ http://freemovement.wordpress.com/2009/02/11/rlctochangename/ http://www.mattheaton.com/?p=14 http://www.webhostingsearch.com/blog/noavailabledomainnames068 http://findportablesolarpower.com/updatesandnews/worldresponsesearthhour2009 / http://www.neuescurriculum.org/nc/?p=12 http://www.ybointeractive.com/blog/2008/09/18/thewrongwaytochooseadomain name/ http://www.marcozehe.de/2008/02/29/easyariatip1usingariarequired/ http://www.universetoday.com/2009/03/16/europesclimatesatellitefailstoleave pad/ http://blogs.sjr.com/editor/index.php/2009/03/27/touchinganerveresponsesto acolumn/ http://blog.privcom.gc.ca/index.php/2008/03/18/yourcreativejuicesrequired/ http://www.taiaiake.com/27 http://www.deadmilkmen.com/2007/08/24/leaveusaloan/ http://www.techgadgets.in/household/2007/06/roboamassagingchairresponsesto yourvoice/ http://blog.swishzone.com/?p=1095 http://www.lorenzogil.com/blog/2009/01/18/mappinginheritancetoardbmswithst ormandlazrdelegates/ http://www.venganza.org/about/openletter/responses/ http://www.middleclassforum.org/?p=405 http://flavio.castelli.name/qjson_qt_json_library http://www.razorit.com/designers_central/howtochooseadomainnameforapree -

Young Parents Demonstration Program: Round Iii Grantee Implementation and Impact Results

YOUNG PARENTS DEMONSTRATION PROGRAM: ROUND III GRANTEE IMPLEMENTATION AND IMPACT RESULTS FINAL REPORT JUNE 2018 Submitted to: EMPLOYMENT AND TRAINING ADMINISTRATION U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR Submitted by: CAPITAL RESEARCH CORPORATION, INC. THE URBAN INSTITUTE WESTAT, INC. Report Authors: John Trutko, Lauren Eyster, Tracy Vericker, Carolyn O’Brien, Alexander Trutko, Sybil Mendonca, Alan Dodkowitz, and Nathan Sick This project has been funded, either wholly or in part, with Federal funds from the Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration under Contract Number DOLQ101A21531- DOLU101A21545/DOLU131A22068 and Contract Number GS-10F-0218W, Task Order1630DC-17-F-00003. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Labor, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement of same by the U.S. Government. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EXHIBITS.................................................................................................................... iii ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................. vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ....................................................................................................... vviii LISTS OF ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................ iix EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ -

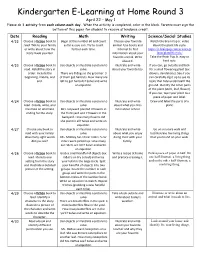

Kindergarten E-Learning at Home Round 3 April 22 – May 1 Please Do 1 Activity from Each Column Each Day

Kindergarten E-Learning at Home Round 3 April 22 – May 1 Please do 1 activity from each column each day. When the activity is completed, color in the block. Parents must sign the bottom of this paper for student to receive attendance credit. Date Reading Math Writing Science/Social Studies 4/22 Choose a fiction book to Begin at the number 60 and count Choose your favorite Watch the Brain Pop Jr. video read. Talk to your family as far as you can. Try to count animal. Use books and about the plant life cycle. or write about how the further each time. Internet to find https://jr.brainpop.com/science/p story made you feel. information about your lants/plantlifecycle/ favorite animal. Write Take the Brain Pop Jr. easy or about it. hard quiz. 4/23 Choose a fiction book to Use objects or illustrate a picture to Illustrate and write If you can, go outside and look read. Retell the story in solve. about your favorite toy. for a small flowering plant (ex: order. Include the There are 8 dogs at the groomer. 3 clovers, dandelions). See if you beginning, middle, and of them got haircuts. How many are can carefully dig it up to see its end. left to get haircuts? Solve and write roots that hide underneath the an equation. ground. Identify the other parts of the plant (stem, leaf, flower). If you can, tape your plant to a piece of paper and label. 4/24 Choose a fiction book to Use objects or illustrate a picture to Illustrate and write Draw and label the parts of a read. -

3. 10 SHANTY � Mencari Cinta Sejati (4:05) 4

Disc Bola 1. Judika Sakura (4:12) 2. Firman Esok Kan Masih Ada (3:43) 3. 10 SHANTY Mencari Cinta Sejati (4:05) 4. 14 J ROCK Topeng Sahabat (4:53) 5. Tata AFI Junior feat Rio Febrian There's A Hero (3:26) 6. DSDS Cry On My Shoulder (3:55) 7. Glenn Pengakuan Lelaki Ft.pazto (3:35) 8. Glenn Kisah Romantis (4:23) 9. Guo Mei Mei Lao Shu Ai Da Mi Lao Shu Ai Da Mi (Original Version) (4:31) 10. Indonesian Idol Cinta (4:30) 11. Ismi Azis Kasih (4:25) 12. Jikustik Samudra Mengering (4:24) 13. Keane Somewhere Only We Know (3:57) 14. Once Dealova (4:25) 15. Peterpan Menunggu Pagi [Ost. Alexandria] (3:01) 16. PeterPan Tak Bisakah (3:33) 17. Peterpan soundtrack album menunggu pagi (3:02) 18. Plus One Last Flight Out (3:56) 19. S Club 7 Have You Ever (3:19) 20. Seurieus Band Apanya Dong (4:08) 21. Iwan Fals Selamat Malam, Selamat Tidur Sayang (5:00) 22. 5566 Wo Nan Guo (4:54) 23. Aaron Kwok Wo Shi Bu Shi Gai An Jing De Zou Kai (3:57) 24. Abba Chiquitita (5:26) 25. Abba Dancing Queen (3:50) 26. Abba Fernando (4:11) 27. Ace Of Base The Sign (3:09) 28. Alanis Morissette Uninvited (4:36) 29. Alejandro Sanz & The Corrs Me Iré (The Hardest Day) (4:26) 30. Andy Lau Lian Xi (4:24) 31. Anggun Look Into Yourself (4:06) 32. Anggun Still Reminds Me (3:50) 33. Anggun Want You to Want Me (3:14) 34. -

Who Is Hikonyan? the Phenomenon of Japanese Yuru-Chara*

Sociology Study, December 2016, Vol. 6, No. 12, 775‐782 D doi: 10.17265/2159‐5526/2016.12.004 DAVID PUBLISHING Who Is Hikonyan? The Phenomenon of Japanese YuruChara* Jillian Rae Sutera Abstract In 2007, Hikonyan was the first winner of the Japan‐wide “yuru‐chara” or “yurui mascot character” competition. Since then, yuru‐chara, or unsophisticated characters, have become a part of the mascot character marketing industry worth over a billion Japanese yen. However, they have not expanded far outside of Japan. This paper looks at yuru‐chara through articles, documentation, literature, and interviews to explore their history and status in Japan, and attempts to explain their rapid rise within the country as well as their lack of presence outside of the country. These resources help explain the design choices of yuru‐chara, the reasoning behind those choices, and what they mean within Japan’s society. They additionally explain how yuru‐chara impact the Japanese market. The paper also explores some Japanese branding and how yuru‐chara can fit into the concept of the Cool Japan Project. Finally, it explores some possibilities of expanding the concept of yuru‐chara to international markets and how they could successfully work abroad. Keywords Cool Japan, branding, authenticity, international markets, mascot characters Hikonyan is a white mascot cat with a red and yellow Japan and Japanese identity could be used internationally “samurai” helmet. He was created in 2007, to celebrate through expansion programs such as the Cool Japan the 400th anniversary of Hikone Castle in Hikone City, Project (Cool Japan/Creative Industries Policy 2013). -

Kawaii Mania Japans Niedlichste Abgründe Isbn 978-3-95889-198-2 Andreas Neuenkirchen Kawaii

KAWAII MANIA JAPANS NIEDLICHSTE ABGRÜNDE ISBN 978-3-95889-198-2 ANDREAS NEUENKIRCHEN KAWAII VOM AUTOR: Matjes mit Wasabi Yoyogi Park MANIA Roppongi Ripper Shinigami Games Japans niedlichste Abgründe Yakuza Requiem KAWAII MANIA KAWAII MANIA JAPANS NIEDLICHSTE ABGRÜNDE JAPANS NIEDLICHSTE ABGRÜNDE ISBN 978-3-95889-198-2 ISBN 978-3-95889-198-2 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Vorwort KAWAIIstory – Eine kurze Geschichte der Niedlichkeit . 8 Kapitel 1 KAWAIIkrieg – Die Schlacht der Maskottchen . 18 Kapitel 2 KAWAIIkonzern – Das Imperium der Niedlichkeit . 32 Kapitel 3 KAWAIIschool – Japans Fräuleinwirtschaftswunder . .50 Kapitel 4 KAWAIIpop – Der Mädchenchor von nebenan . 64 Kapitel 5 KAWAIIfashion – Niedlich auf dem Laufsteg . 82 Kapitel 6 1 . Auflage KAWAIIkunst – Nicht nur niedlich . 96 © Conbook Medien GmbH, Neuss 2019 Alle Rechte vorbehalten . Kapitel 7 KAWAIIgames – Japaner spielen (ein bisschen) anders . 116 www .conbook-verlag .de Kapitel 8 Dieses Werk wurde vermittelt durch Aenne Glienke | Agentur für Au- KAWAIIfood – Süß ohne sauer . 136 toren und Verlage, www .AenneGlienkeAgentur .de . Kapitel 9 Einbandgestaltung: Andrea Janas, München KAWAIImetropolis – Hotspots der Niedlichkeit . 148 Einbandinnenseiten: Mariam »Machi« Taherpour Satz: Weiß-Freiburg GmbH – Grafik und Buchgestaltung Kapitel 10 Druck und Verarbeitung: Himmer GmbH Druckerei, Augsburg KAWAIIworld – Japan ist nur der Anfang . 164 Printed in Germany Anhang KAWAIIglossar . 180 ISBN 978-3-95889-198-2 Bildnachweis . 188 KAWAII MANIA KAWAII MANIA JAPANS NIEDLICHSTE ABGRÜNDE JAPANS NIEDLICHSTE ABGRÜNDE ISBN 978-3-95889-198-2 ISBN 978-3-95889-198-2 VORWORT KAWAII MANIA KAWAII MANIA JAPANS NIEDLICHSTE ABGRÜNDE JAPANS NIEDLICHSTE ABGRÜNDE ISBN 978-3-95889-198-2 ISBN 978-3-95889-198-2 VORWORT KAWAIIstory Eine kurze Geschichte der Niedlichkeit LETZTENS KAM MAL WIEDER POST vom Finanzamt in Meguro, dem Stadtteil Tokios, in dem ich lebe . -

Basic Geography Suggested Length: 6 Weeks

Bracken County Schools Curriculum Guide Social Studies Grade 6 Unit 1: Basic Geography Suggested Length: 6 weeks Essential Questions Program of Studies and Core Content Key Terms and Vocabulary Classroom Instruction and Assessment Student will: Program of Studies 1. How have H-1 examine how human and physical 5 Themes of Locate and identify various places of local interest, geographic geography influence past decisions and Geography using map of hometown. Look for items of specific factors events. Location (Absolute economic, social, cultural, or historical interest. 6.4.1.1 influenced past H-2 analyze the influence of geographic and Relative) DOK 3 decisions and factors on past decisions and events. Place Demonstrate how geographic tools (maps, globes, etc.) events? H-3 evaluate past, current, and future issues Region are used to find absolute and relative location. 6.4.1.1. of land use (e.g., preservation, development, Movement DOK 3 2. How can the modification) from geographic perspectives. Human- Cooperative Learning Activity: Using Technology: five themes of G-1 examine patterns on Earth’s surface, Environment Create a visual aid (Power Point, Brochure, etc.) geography be using geographic tools (e.g., maps, globes), to Interaction explaining and giving examples of the 5 Themes of used to interpret identify where things (e.g., people, places, Tools such as Maps, Geography to share with the rest of the class. 6.4.2.1 and evaluate the landmarks) are, how they are arranged, and Globes, Projections DOK 2 impact of why they are in particular locations. Seasons (Spring, Create-A-Country: The students will create their own human G-2 analyze the physical and human Winter, Autumn, country and include the following: Natural Resources, settlement and characteristics of places and regions. -

Steve Manchester “St. Ermin's Hotel”

Member since 1951 Volume 81- ISSUE 09– SEPTEMBER 2017 GREATER SAN ANTONIO CAMERA CLUB WWW.GSACC.ORG Competition Results, Page 2 New Member Spotlight Page 6 Steve Manchester CREATIVE tied for 1st place “St. Ermin’s Hotel” FLASH — September 2017 Competition September 2017 - PRINT Competition Images PICTORIAL MONOCHROME PHOTOJOURNALISM 1st “Bee in Space” John Kain 1st “Feeding the Pigeons” Steve Manchester 1st “Airport Rail” Steve Manchester 2nd “Key West Kissing Sailor Monument” Peter Florczak 2nd “Boats Docked in the Fog” Peter Florczak 3rd “Taking a Shopping Break in the Shade” John Kain 3rd “Take My Picture” Peter Aradi 3rd “Sibling Love” Jack Smith 3rd “Happy Memories Bring a Tear” Nancy Tschirhart-Brooks HM “New Restaurant in the Old City” Peter Aradi HM “White Tiger” Jack Smith PICTORIAL COLOR CREATIVE 1st “Maine Lighthouse Reflection” Peter Florczak 1st “Dragon Spout” Peter Aradi 2nd “Brindle Longhorn” James Moseley 1st “St, Irmin’s Hotel” Steve Manchester 2nd “Purple Lily” Jack Smith 2nd “Prayer Candles” John Kain 3rd “The New Wilford Hall” Steve Manchester 3rd “Back Woods Art” Peter Florczak HM “Forbidden City” Peter Aradi no HM ASSIGNMENT NATURE 1st “Texas Beer Choices” Jack Smith 1st “Muddy Cub” Jack Smith 2nd “Big Choice of Beer” Peter Florczak 2nd “Zebra Longwing” Steve Manchester 3rd “Octoberfest - Scary Fun” Nancy Tschirhart-Brooks 3rd “Dragonfly” James Moseley HM “Beer-B-Q” John Kain HM “Sunset in the Woods” Peter Florczak Judges were: : John Kain, Tim Kirkland and Mary Hunsicker ASSIGNMENTS for 2017—2018 Images submitted for this category must have been taken after November 1, 2016. Assignment subject must occupy approximately 25% of the image area except on subject where specifically waived. -

NANA Starring MIKA NAKASHIMA the End Mp3, Flac, Wma

NANA starring MIKA NAKASHIMA The End mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Pop Album: The End Country: Japan Released: 2006 Style: Power Pop, Pop Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1525 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1983 mb WMA version RAR size: 1946 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 394 Other Formats: WMA AA MMF DMF AIFF XM AHX Tracklist 1 Hitoiro 5:21 2 Eyes For The Moon 3:39 3 Glamorous Sky 4:26 4 Blowing Out 3:27 5 My Medicine 3:37 6 Neglest Mind 3:57 7 Real World 4:08 8 Isolation 4:42 9 Blood 4:39 10 Hitoiro (Altanative) 5:06 11 My Way 4:19 Notes Released under the name Nana starring Mika Nakashima Other versions Title Category Artist Label Category Country Year (Format) Sony Music NANA starring MIKA The End (CD, AICL 1783 Associated AICL 1783 Japan 2006 NAKASHIMA* Album) Records Sony Music NANA starring MIKA The End (CD, Hong 88697056132 Associated 88697056132 2006 NAKASHIMA* Album) Kong Records The End Sony Music NANA starring MIKA AIJL-5303-4 (2xLP, Album, Associated AIJL-5303-4 Japan 2007 NAKASHIMA* RE) Records Inc. NANA starring MIKA The End (CD, ADCI 80301 SAR ADCI 80301 Japan 2006 NAKASHIMA* Album, Promo) Related Music albums to The End by NANA starring MIKA NAKASHIMA 1. Nana Mouskouri - Alone 2. Mika Nakashima - Love 3. Nana Mouskouri - The Very Best Of Nana Mouskouri 4. Mika Nakashima - Helpless Rain 5. Ko Nakashima - Raft 6. Red Ingle, The Happy Jesters - Starring The Country Music Of Red Ingle Also Starring The Happy Jesters 7. -

Japanese Mascots: Diplomatic Tool, Domestic Escapism

JAPANESE MASCOTS: DIPLOMATIC TOOL, DOMESTIC ESCAPISM © 2019 By Gwenafaye A. McCormick A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies Croft Institute for International Studies Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi May 2019 Approved: __________________________________ Advisor: Dr. Noell Wilson __________________________________ Reader: Dr. Minjoo Oh __________________________________ Reader: Dr. Joshua Howard 2 ABSTRACT In Japan, mascots are not only representatives of sports teams and sugary cereals, but are vital diplomatic tools of communication and domestic tools of escapism. Though a multitude of mascots exist, scholarship on the topic tends to portray the body of mascots as one-dimensional. This thesis analyzes the modern mascot field and provides previously undefined categories for mascots based on their application, as their absence hinders further analysis. These definitions also describe the subversive social space that mascots inhabit in Japanese society and allow the thesis to examine consumers’ relationships with mascots. An analysis of the U.S. and Israeli embassy mascots reveals that, through these Japanese-styled mouthpieces, foreign countries can more gently promote their goals to the Japanese public. A historical contextualization of mascots elucidates their cultural heft and provides a framework to examine the mascots of the U.S. and Israeli embassies in Japan as soft diplomacy actors. Embassy mascots are unique in their form and application, presenting a Japanese-styled mouthpiece whose goal is to alleviate the country-specific anxieties that Japanese people experience – a truly usable manner of soft power given their agency. While embassy mascot’s efficacy, longevity, and matters of who controls the soft power they embody are debatable, further scholarship should examine them seriously as possibly affecting diplomatic relations with Japan and not dismiss them as simply another fad.