Owning Versus Renting: Thoughts on Housing Policy, Tax Incentives, and Middle Class Dreams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

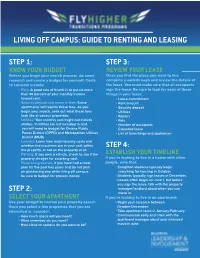

Guide to Renting and Leasing Digital

LIVING OFF CAMPUS: GUIDE TO RENTING AND LEASING STEP 1: STEP 3: KNOW YOUR BUDGET REVIEW YOUR LEASE Before you begin your search process, do some Once you find the place you want to live, research and create a budget for yourself. Costs complete a walkthrough and review the details of to consider include: the lease. You must make sure that all occupants Rent: A good rule of thumb is to put no more sign the lease. Be sure to look for each of these than 30 percent of your monthly income things in your lease: toward rent. Lease commitment Security deposit and move-in fees: Some Rent amount apartments will require these fees. As you Security deposit begin your search, seek out what these fees Utilities look like at various properties. Repairs Utilities: Your monthly rent might not include Pets utilities. If utilities are not included in rent, Number of occupants you will need to budget for Omaha Public Extended leave Power District (OPPD) and Metropolitan Utilities List of furnishings and appliances District (MUD). Laundry: Learn how much laundry costs and whether the machines are in your unit, within STEP 4: the property, or not on the property at all. Parking: If you own a vehicle, check to see if the ESTABLISH YOUR TIMELINE property chrages for a parking spot. If you’re looking to live in a house with other Food and groceries: If you have had a meal people, note that: plan for the past two years and do not plan Creighton students typically begin on purchasing one while living o campus, searching for housing in October. -

So… You Wanna Be a Landlord? Income Tax Considerations for Rental Properties

So… you wanna be a landlord? Income tax considerations for rental properties November 2020 Jamie Golombek & Debbie Pearl-Weinberg Tax and Estate Planning, CIBC Private Wealth Management Considering becoming a landlord? You’re not alone. According to recent a CIBC poll, more than one in four Canadian homeowners are either already landlords (15%) or plan to earn rental income (11%) by renting out space in their primary residence or from a separate rental property. And, nearly two in five (37%) homeowners say they’d opt for a home with a source of rental income if buying a home today. While there are many financial and legal issues to consider as a landlord, make sure that you don’t overlook tax considerations of earning rental income. Whether you’re purchasing a residential or commercial property for the purpose of leasing it out, or you are considering renting your home or part of your home, this report highlights some of the more common tax issues you should consider before taking the plunge! Rental property or business? The first question you need to consider is whether the rental income you earn will be treated as income from property (i.e. investment income) or as income from a business, since each has different tax implications. When you rent out real estate, your income is treated as property income if you provide only basic services, such as utilities (e.g. light and heating), parking and laundry facilities. If you provide additional services, such as cleaning, security and / or meals, then it may be considered a business. -

Ph6.1 Rental Regulation

OECD Affordable Housing Database – http://oe.cd/ahd OECD Directorate of Employment, Labour and Social Affairs - Social Policy Division PH6.1 RENTAL REGULATION Definitions and methodology This indicator presents information on key aspects of regulation in the private rental sector, mainly collected through the OECD Questionnaire on Affordable and Social Housing (QuASH). It presents information on rent control, tenant-landlord relations, lease type and duration, regulations regarding the quality of rental dwellings, and measures regulating short-term holiday rentals. It also presents public supports in the private rental market that were introduced in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Information on rent control considers the following dimensions: the control of initial rent levels, whether the initial rents are freely negotiated between the landlord and tenants or there are specific rules determining the amount of rent landlords are allowed to ask; and regular rent increases – that is, whether rent levels regularly increase through some mechanism established by law, e.g. adjustments in line with the consumer price index (CPI). Lease features concerns information on whether the duration of rental contracts can be freely negotiated, as well as their typical minimum duration and the deposit to be paid by the tenant. Information on tenant-landlord relations concerns information on what constitute a legitimate reason for the landlord to terminate the lease contract, the necessary notice period, and whether there are cases when eviction is not permitted. Information on the quality of rental housing refers to the presence of regulations to ensure a minimum level of quality, the administrative level responsible for regulating dwelling quality, as well as the characteristics of “decent” rental dwellings. -

Renting Vs. Buying

renting vs. buying: 6 things to consider After years of renting and frequent moving, you may start to ask yourself: Should I buy a house? While many experts have weighed in on the pros and cons of renting vs. buying, the truth is-it depends on your individual situation. So, if you're not sure if renting or owning is right for you, here are a few things to consider. 1. Where do you want to live? If you're looking to live in a big city, you may have more options in the rental market. But if you prefer the suburbs, buying may be a better option since single family home rentals can be few and far between. 2. How long do you plan to stay? Consider your "five-year plan." If your job situation is in flux or you plan to move again in a few years, renting may make more sense. On the other hand, if you're ready to settle down in a certain area, making the investment to buy could pay off long-term. 3. Are you ready to be your own landlord? When you're renting and your sink springs a leak, your landlord will handle the maintenance and cost of any repairs. But if you're the homeowner, that responsibility falls on you. On the upside, owning your own home also gives you the freedom to do your own remodeling or repairs and to hire the contractor of your choice. 4. How important is long-term payoff? Buying a house is an investment in your future. -

Owning Or Renting in the US: Shifting Dynamics of the Housing Market

PENN IUR BRIEF Owning or Renting in the US: Shifting Dynamics of the Housing Market BY SUSAN WACHTER AND ARTHUR ACOLIN MAY 2016 Photo by Joseph Wingenfeld, via Flickr. 2 Penn IUR Brief | Owning or Renting in the US: Shifting Dynamics of the Housing Market Full paper is Current Homeownership Outcomes available on the Penn IUR website at penniur.upenn.edu The nation’s homeownership rate was remarkably steady between the 1960s and the 1990s, following a rapid rise in the two decades after World War II, with two-thirds of the nation’s households owning. Over the most recent 20 years, however, homeownership outcomes have been volatile. The research we summarize here identifies drivers of this volatility and the newly observed lows in homeownership. We ask under what circumstances this is a “new normal.” We begin by reviewing current homeownership outcomes. In the section which follows we present evidence on the causes of the current lows. In the third section we develop scenarios for homeownership rates going forward. The U.S. homeownership rate is now at a 48 year low at 63.7 percent (Fig. 1). Homeownership rates have declined for all demographic age groups (Table 1). Since 2006, the number of households who own their home in the U.S. has decreased by 674,000 while the number of renters has increased by over 8 million (Fig. 2). This is a dramatic reversal from the rate of increase of more than 1 percent annually in the number of homeowners from 1980 to 2000 (U.S. Census 2016a)1. -

2016 Frederick County Affordable Housing Needs Assessment

FREDERICK COUNTY AFFORDABLE HOUSING NEEDS ASSESSMENT Frederick County, MD November 2016 520 NORTH MARKET STREET TANEY VILLAGE APARTMENTS VICTORIA PARK BELL COURT SENIOR LIVING TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………………….…1 Task 1: County Demographic Analysis...…………………………………………………………………....20 Task 2: Rental and Sales Price Trends …...………………………………….....................................................27 Task 3: Analysis of Residential Construction………………….…………………………………………….30 Task 4: Housing Affordability Analysis….………………...……..……...............................................................35 Task 5: Affordability Index….……………………………….......……...............................................................37 Task 6: Housing Gap Analysis……….…………………………………………………………………….44 Task 7: Housing Gap Trends……………………………………………………………………………….47 Task 8: Density Bonuses…..………………..……………………………………………………………….51 Task 9: MPDU Program Analysis…..……………………………………………………………………….52 Task 10: Homelessness Action Plan Summary……...……………………….………………………………54 Task 11: Meet with Representatives………..……...……………………….………………………………56 Task 12: Public Private Partnerships…..………...………………………………………………………….57 Task 13: Foreclosure Rates……….………………………………..……………………………………….58 Task 14: Housing Needs by Demographic Characteristics…………………….…………………………...60 Component 2.1.1: Inventory of Affordable and Accessible Housing………………………………………63 Component 2.1.2: Existing Affordable and Accessible Housing Market…….……………………………..64 Component 2.1.3: Location and Distribution of Affordable -

An Introduction to Renting Residential Real Property

An Introduction to Renting Residential Real Property State of Hawaii Department of Taxation Revised March 2020 Overview This brochure provides basic information on the application of the general excise tax and transient accommodations tax to lessors of residential real property located in Hawaii. This brochure complements our brochures “An Introduction to the General Excise Tax” and “An Introduction to the Transient Accommodations Tax.” Please refer to these brochures for more information on these taxes. If you have any questions, please call us. Our contact information is provided at the back of this brochure. _______________ Note: This brochure provides general information and is not a substitute for legal or other professional advice. The information provided in this brochure does not cover every situation and is not intended to replace the law or change its meaning. If there is a conflict between the text in this brochure and the law, then the application of tax will be based on the law and not on this brochure. Table of Contents General Information ......................................... 1 What is Subject to Tax ..................................... 4 Managing Agents ............................................. 5 Registration & Licensing .................................. 7 Tax Forms & Filing Requirements ................... 9 Where to Get More Information ..................... 13 General Information 1. If I rent out my house or a room in my house, does that mean I am in business? Yes. If you receive rental income from renting out part or all of your house, condominium, apartment, second home, vacation home, or any other residential real property (“real property”) located in Hawaii, then you are engaging in a taxable business activity. 2. If I rent out my house, do I have to pay taxes? Yes. -

The Long-Run Relationship Between House Prices and Rents

Finance and Economics Discussion Series Divisions of Research & Statistics and Monetary Affairs Federal Reserve Board, Washington, D.C. The Long-Run Relationship between House Prices and Rents Joshua Gallin 2004-50 NOTE: Staff working papers in the Finance and Economics Discussion Series (FEDS) are preliminary materials circulated to stimulate discussion and critical comment. The analysis and conclusions set forth are those of the authors and do not indicate concurrence by other members of the research staff or the Board of Governors. References in publications to the Finance and Economics Discussion Series (other than acknowledgement) should be cleared with the author(s) to protect the tentative character of these papers. The Long-Run Relationship between House Prices and Rents Joshua Gallin, Federal Reserve Board ∗ September 2004 Abstract I show that when house prices are high relative to rents (that is, when the rent-price ratio is low) changes in real rents tend to be larger than usual and changes in real prices tend to be smaller than usual. Standard error-correction models provide inconclusive results about the predictive power of the rent-price ratio at a quarterly frequency. I use a long-horizon regression approach to show that the rent-price ratio helps predict changes in real rents and real prices over three-year periods. This result withstands the inclusion of a measure of the user cost of capital. I show that a long- horizon regression approach can yield biased estimates of the degree of error correction if prices have a unit root but do not follow a random walk. I construct bootstrap distributions to conduct appropriate inference in the presence of this bias. -

Housing Bubbles

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES HOUSING BUBBLES Edward L. Glaeser Charles G. Nathanson Working Paper 20426 http://www.nber.org/papers/w20426 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 August 2014 Edward Glaeser thanks the Taubman Center for State and Local Government for financial support. William Strange (the editor) provided much guidance and Rajiv Sethi both provided excellent comments. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. At least one co-author has disclosed a financial relationship of potential relevance for this research. Further information is available online at http://www.nber.org/papers/w20426.ack NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2014 by Edward L. Glaeser and Charles G. Nathanson. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Housing Bubbles Edward L. Glaeser and Charles G. Nathanson NBER Working Paper No. 20426 August 2014 JEL No. R0,R31 ABSTRACT Housing markets experience substantial price volatility, short term price change momentum and mean reversion of prices over the long run. Together these features, particularly at their most extreme, produce the classic shape of an asset bubble. In this paper, we review the stylized facts of housing bubbles and discuss theories that can potentially explain events like the boom-bust cycles of the 2000s. -

Real Property Rental 20190227.Pub

R P R You are in the business of renting or leasing real office buildings property. If you rent residential property for less parking and storage facilities than 30 days, see the Hotel/ Motel Sales Tax apartments/homes/duplex/triplex/fourplexes Brochure. (Mesa Tax Code 5-10-445) stores/factories/farmland banquet and meeting halls The tax rate is 2.0% of the gross income. vacation rentals Mesa Business Code 045 ME (Residential Rental) Mesa Business Code 213 ME (Commercial Lease/ Licensing For Use) Maricopa County Business Code 013 MAR 1. You have one or more non-residential rental units. (Commercial Lease, tax rate .5%) 2. You have 2 or more residential units available for rent in the State. 3. You have 1 residential unit and one or more You may choose to charge the tax separately or commercial units. you may include tax in your sales price. If you include tax in your sales price, you may factor in 4. If you only own one residential single-family order to “compute” the amount of tax included in home in the state and it is located in Mesa, your gross income for deduction purposes and and rented to multiple unrelated tenants, such obtain the “Net Taxable”. To determine the factor, as college students, it would be taxable to the add one (1.00) to the total of state, county, and City of Mesa. If this same home is rented to a city tax rates. single family or person, it would not be taxable. If you have a broker or property manager, all Mesa units would be taxable. -

Understanding and Mitigating Rental Risk Todd Sinai the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania and the National Bureau of Economic Research

Understanding and Mitigating Rental Risk Todd Sinai The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania and the National Bureau of Economic Research Abstract The decision of whether to rent or own a home should involve an evaluation of the relative risks and the relative costs of the two options. It is often assumed that renting is less risky than homeownership, but that is not always the case. Which option is riskier depends on the risk source and household characteristics. This article provides a framework for understanding the sources of risk for renters. It outlines the most important determinants of risk: volatility in the total cost of obtaining housing, changes in housing costs after a move, and the correlation of rents with incomes. The article characterizes the magnitudes of those risks and discusses how the effects of risk vary across renter types and U.S. metropolitan areas. In addition, the article shows that renters spend less of their cash flow on housing than do otherwise equivalent owners and, thus, are better able to absorb housing cost risk. Finally, potential policy approaches to rental housing that avoid increasing rent risk are discussed. A simple way to maintain renters’ capacity to absorb rent risk is to avoid sub- sidies that result in an incentive to consume a larger rental housing quantity. Targeting rental subsidies to more mobile households or those living in low-volatility cities, where renting is less risky, should be considered. Long-term leases would provide an intermedi- ate position between renting annually and owning but are currently rare. Introduction Much of the discussion about government subsidies that are targeted at homeownership or renting focuses on the subsidies’ effects on the relative cost of owning versus renting. -

Factors to Consider When Looking for a Rental

Factors to Consider When Looking for a Rental There are a number of things to consider when looking for accommodations off-campus. The cost of living includes rent as well as utilities, food, transportation and amenities. Other factors to look into when it comes to prices are the building or area specific charges. The information provided below will help you navigate your way to finding a good home for you while you complete your CSUDH degree. Location: Do I feel safe? Is this environment for me? How far away am I from campus? How long will it take me to travel? What other locations are around me? These are just a few questions to ask yourself when identifying an area to which to live. Here are a few tips: Observe the neighborhood: check out the atmosphere during the day, in the evening and weekends. Ask if it is for you. Is it too noisy? Too Quite? Meet the neighbors: Check out who you will be living next too. Do they have kids? Are they fellow college students? Do they keep to themselves? Travel: Observe the traffic. How long will it take you to get to school/work? Is there a Bus route? How much will it cost in gas to travel to school/work? Is parking available? How much is parking? Convenience: What is nearby? Do you have access to a grocery stores? Are there too many stores? Too Little? Can you walk to them or do you have to drive? Apartment vs. House vs. Room: Depending on the city, the availability of rentals can differ.