Measurement of House Price Bubbles: a Case in Sydney

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 2 Tax Expenditures and Housing

Chapter 2 Tax expenditures and housing Judith Yates This chapter provides an assessment of the scale and distribution of the key tax expenditures for housing in the Australian tax system. The aggregate estimates of these tax expenditures suggest they are extremely large (of the order of $50 billion per year in total), with the vast majority arising from the concessions to owner-occupied housing. They are also distributed perversely, with the greatest benefits going to high income households at a time when they need them least. The chapter indicates some changes that might be made to make the tax treatment of housing more efficient and more equitable. 1 Introduction The aim of this chapter is to provide an assessment of the scale and distribution of the key tax expenditures for housing in the Australian tax system and to indicate some of the changes that might be made to make the tax treatment of housing more efficient and more equitable. The key tax bases that are relevant to housing in the Australian tax system are, at a federal level, the (individual) income and consumption (GST) tax bases and, at a state 1 or local level, the transactions (duties) and wealth (land taxes and rates) tax bases. A brief description of the various tax laws for housing is in Chapter 1 of this volume. Essentially, the imputed rent and capital gains of owner-occupied housing are exempt from income tax. The cost of financing the purchase and other expenses are not deductible. Rental properties are subject to income tax, including CGT, and are eligible for a 2.5% annual depreciation allowance on the construction cost of the building. -

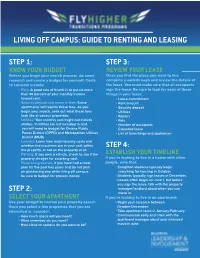

Guide to Renting and Leasing Digital

LIVING OFF CAMPUS: GUIDE TO RENTING AND LEASING STEP 1: STEP 3: KNOW YOUR BUDGET REVIEW YOUR LEASE Before you begin your search process, do some Once you find the place you want to live, research and create a budget for yourself. Costs complete a walkthrough and review the details of to consider include: the lease. You must make sure that all occupants Rent: A good rule of thumb is to put no more sign the lease. Be sure to look for each of these than 30 percent of your monthly income things in your lease: toward rent. Lease commitment Security deposit and move-in fees: Some Rent amount apartments will require these fees. As you Security deposit begin your search, seek out what these fees Utilities look like at various properties. Repairs Utilities: Your monthly rent might not include Pets utilities. If utilities are not included in rent, Number of occupants you will need to budget for Omaha Public Extended leave Power District (OPPD) and Metropolitan Utilities List of furnishings and appliances District (MUD). Laundry: Learn how much laundry costs and whether the machines are in your unit, within STEP 4: the property, or not on the property at all. Parking: If you own a vehicle, check to see if the ESTABLISH YOUR TIMELINE property chrages for a parking spot. If you’re looking to live in a house with other Food and groceries: If you have had a meal people, note that: plan for the past two years and do not plan Creighton students typically begin on purchasing one while living o campus, searching for housing in October. -

So… You Wanna Be a Landlord? Income Tax Considerations for Rental Properties

So… you wanna be a landlord? Income tax considerations for rental properties November 2020 Jamie Golombek & Debbie Pearl-Weinberg Tax and Estate Planning, CIBC Private Wealth Management Considering becoming a landlord? You’re not alone. According to recent a CIBC poll, more than one in four Canadian homeowners are either already landlords (15%) or plan to earn rental income (11%) by renting out space in their primary residence or from a separate rental property. And, nearly two in five (37%) homeowners say they’d opt for a home with a source of rental income if buying a home today. While there are many financial and legal issues to consider as a landlord, make sure that you don’t overlook tax considerations of earning rental income. Whether you’re purchasing a residential or commercial property for the purpose of leasing it out, or you are considering renting your home or part of your home, this report highlights some of the more common tax issues you should consider before taking the plunge! Rental property or business? The first question you need to consider is whether the rental income you earn will be treated as income from property (i.e. investment income) or as income from a business, since each has different tax implications. When you rent out real estate, your income is treated as property income if you provide only basic services, such as utilities (e.g. light and heating), parking and laundry facilities. If you provide additional services, such as cleaning, security and / or meals, then it may be considered a business. -

Rent Imputation for Welfare Measurement

WPS7103 Policy Research Working Paper 7103 Public Disclosure Authorized Rent Imputation for Welfare Measurement A Review of Methodologies and Empirical Findings Public Disclosure Authorized Carlos Felipe Balcazar Lidia Ceriani Sergio Olivieri Marco Ranzani Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Poverty Global Practice Group November 2014 Policy Research Working Paper 7103 Abstract As well acknowledged in the literature, housing is often provides an extensive review of different methods to impute the dominant consumption good for most households. As rent, commonly used for welfare analysis. It also gives such, it should be included in a comprehensive welfare an overview of how this problem has been addressed by aggregate to measure people’s living standards accurately. other economic domains, namely national accounts, price However, assigning a value to the flow of the dwelling indices, purchasing power parities, and taxation. Finally, for homeowners and nonmarket tenants is problematic. after setting up a theoretical framework, the paper sum- Over the last decades several estimation techniques have marizes the empirical findings about the distributional been proposed and implemented by practitioners covering impact of including imputed rents in welfare aggregates. from very simple to sophisticated approaches. This paper This paper is a product of the Poverty Global Practice Group. It is part of a larger effort by the World Bank to provide open access to its research and make a contribution to development policy discussions around the world. Policy Research Working Papers are also posted on the Web at http://econ.worldbank.org. The authors may be contacted at solivieri@ worldbank.org. The Policy Research Working Paper Series disseminates the findings of work in progress to encourage the exchange of ideas about development issues. -

Ph6.1 Rental Regulation

OECD Affordable Housing Database – http://oe.cd/ahd OECD Directorate of Employment, Labour and Social Affairs - Social Policy Division PH6.1 RENTAL REGULATION Definitions and methodology This indicator presents information on key aspects of regulation in the private rental sector, mainly collected through the OECD Questionnaire on Affordable and Social Housing (QuASH). It presents information on rent control, tenant-landlord relations, lease type and duration, regulations regarding the quality of rental dwellings, and measures regulating short-term holiday rentals. It also presents public supports in the private rental market that were introduced in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Information on rent control considers the following dimensions: the control of initial rent levels, whether the initial rents are freely negotiated between the landlord and tenants or there are specific rules determining the amount of rent landlords are allowed to ask; and regular rent increases – that is, whether rent levels regularly increase through some mechanism established by law, e.g. adjustments in line with the consumer price index (CPI). Lease features concerns information on whether the duration of rental contracts can be freely negotiated, as well as their typical minimum duration and the deposit to be paid by the tenant. Information on tenant-landlord relations concerns information on what constitute a legitimate reason for the landlord to terminate the lease contract, the necessary notice period, and whether there are cases when eviction is not permitted. Information on the quality of rental housing refers to the presence of regulations to ensure a minimum level of quality, the administrative level responsible for regulating dwelling quality, as well as the characteristics of “decent” rental dwellings. -

Home Thoughts from Abroad: When Foreigners Purchase U.S

HOME THOUGHTS FROM ABROAD: WHEN FOREIGNERS PURCHASE U.S. HOMES Authors PROLOGUE Stanley C. Ruchelman Michael J.A. Karlin Your real estate partner comes into your office, saying: Tags We have a new client, Mr. N.R.A., who is buying the most expensive 897 house in town. Here is what he wants to do: not buy it in his own 1445 name; not pay rent; allow his wife and children (some of whom are Estate Tax U.S. residents) to use the house; not pay estate tax, should he die; F.I.R.P.T.A. Withholding not pay gift tax, should he give it away; not file a tax return; and not Gift Tax pay tax when he sells the property. Nonresident “No sweat,” I told him. “We can do it; my tax partner is the smartest planner in town.” Real Estate Structure Planning Is it doable? Does our quiver hold enough tax planning arrows to meet all those Transparency goals? U.S.R.P.I. U.S.R.PH.C. INTRODUCTION This report is concerned with a seemingly simple subject: how to plan the acquisition, ownership, and disposition — by sale, exchange, gift, or bequest — of residential real property in the United States for a nonresident alien client.1 For many Americans, as we are regularly reminded, the purchase of a home is the single largest financial transaction of our lives and, because it is the policy of the federal and state governments to encourage homeownership, this investment ben- This article was originally efits from extraordinary tax advantages. -

Housing and the Economy: Policies for Renovation

Housing and the Economy: Policies for Renovation Chapter from forthcoming: Economic Policy Reforms 2011 Going for Growth Economic Policy Reforms 2011 Going for Growth © OECD 2011 PART II Chapter 4 Housing and the Economy: 1 Policies for Renovation 1 This chapter compares a number of housing policies for a range of OECD countries and concludes that badly-designed policies can have substantial negative effects on the economy, for instance by increasing the level and volatility of real house prices and preventing people from moving easily to follow employment opportunities. Some of these policies played an important role in triggering the recent financial and economic crisis and could also slow down the recovery. The chapter makes some recommendations for efficient and equitable housing policies that can also contribute to macroeconomic stability and growth. 3 II.4. HOUSING AND THE ECONOMY: POLICIES FOR RENOVATION Summary and conclusions Badly-designed housing policies played an important role in triggering the recent economic and financial crisis. This chapter investigates how housing policies should be designed to ensure adequate housing for citizens, support growth in long-term living standards and strengthen macroeconomic stability. Governments intervene in housing markets to enhance people’s housing opportunities and to ensure equitable access to housing. These interventions include fiscal measures, such as taxes and subsidies; the direct provision of social housing or rent allowances; and various regulations influencing the quantity, quality and price of housing. Housing policies also have a bearing on overall economic performance and living standards, in that they can influence how households use their savings as well as residential and labour mobility, which is crucial for reallocating workers to new jobs and geographical areas. -

The Impact of Market Imperfections on Real Estate Returns and Optimal Investor Portfolios

The Impact of Market Imperfections on Real Estate Returns and Optimal Investor Portfolios Crocker H. Liu, New York University Terry V. Grissom, Texas A&M University David J. Hartzell, University of North Carolina This study investigates the consequences of several imperfections associated with real estate markets on pricing and optimal investor portfolios from a CAPM context. CAPM assumptions are relaxed to recognize illiquidity, the consumption and investment attributes of owner-occupied housing, and a mildly segmented market structure. The study finds that relaxing the CAPM assumptions lead to a separate pricing paradigm for financial assets, income-producing real estate and owner-occupied housing respectively, that a "dividend effect" arises for real estate as the result of illiquidity, and that illiquidity reduces the extent to which investors hold real estate in their portfolios. Introduction Most theoretical research on the investment decisions of investors and equilibrium asset prices focuses almost exclusively on financial assets although some literature exists on other asset classes such as human capital (c.f. Mayers [13] and Brito [5]) and durables (c.f. Bosch [3] and Grossman and Laroque [12]). One class of assets excluded from much theoretical inquiry in the past is real estate. The unstated implication is that the results of equilibrium asset pricing and investor's portfolio demand for stocks is directly applicable to real estate. However, real estate and the market within which it trades exhibit certain features that might distinguish the pricing of real estate from that of financial assets. The purpose of this study is to use the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) framework to investigate what consequences arise from recognizing real estate imperfections on the pricing of real estate and other financial assets and on the composition of optimal investor portfolios. -

Renting Vs. Buying

renting vs. buying: 6 things to consider After years of renting and frequent moving, you may start to ask yourself: Should I buy a house? While many experts have weighed in on the pros and cons of renting vs. buying, the truth is-it depends on your individual situation. So, if you're not sure if renting or owning is right for you, here are a few things to consider. 1. Where do you want to live? If you're looking to live in a big city, you may have more options in the rental market. But if you prefer the suburbs, buying may be a better option since single family home rentals can be few and far between. 2. How long do you plan to stay? Consider your "five-year plan." If your job situation is in flux or you plan to move again in a few years, renting may make more sense. On the other hand, if you're ready to settle down in a certain area, making the investment to buy could pay off long-term. 3. Are you ready to be your own landlord? When you're renting and your sink springs a leak, your landlord will handle the maintenance and cost of any repairs. But if you're the homeowner, that responsibility falls on you. On the upside, owning your own home also gives you the freedom to do your own remodeling or repairs and to hire the contractor of your choice. 4. How important is long-term payoff? Buying a house is an investment in your future. -

Owning Or Renting in the US: Shifting Dynamics of the Housing Market

PENN IUR BRIEF Owning or Renting in the US: Shifting Dynamics of the Housing Market BY SUSAN WACHTER AND ARTHUR ACOLIN MAY 2016 Photo by Joseph Wingenfeld, via Flickr. 2 Penn IUR Brief | Owning or Renting in the US: Shifting Dynamics of the Housing Market Full paper is Current Homeownership Outcomes available on the Penn IUR website at penniur.upenn.edu The nation’s homeownership rate was remarkably steady between the 1960s and the 1990s, following a rapid rise in the two decades after World War II, with two-thirds of the nation’s households owning. Over the most recent 20 years, however, homeownership outcomes have been volatile. The research we summarize here identifies drivers of this volatility and the newly observed lows in homeownership. We ask under what circumstances this is a “new normal.” We begin by reviewing current homeownership outcomes. In the section which follows we present evidence on the causes of the current lows. In the third section we develop scenarios for homeownership rates going forward. The U.S. homeownership rate is now at a 48 year low at 63.7 percent (Fig. 1). Homeownership rates have declined for all demographic age groups (Table 1). Since 2006, the number of households who own their home in the U.S. has decreased by 674,000 while the number of renters has increased by over 8 million (Fig. 2). This is a dramatic reversal from the rate of increase of more than 1 percent annually in the number of homeowners from 1980 to 2000 (U.S. Census 2016a)1. -

Asset-Price Inflation and Rent Seeking: a Total-Returns

Asset-Price Inflation and Rent Seeking: A Total-Returns Profile of Economic Polarization in America Michael Hudson Based on work with Dirk Bezemer with charts by Howard Reed 1 Asset-Price Inflation and Rent Seeking: A Total-Returns Profile of Economic Polarization in America “More than half of all Americans feel pressure and strain, according to the April 2019 Global Emotions Report published by Gallup. Most (55%) Americans recall feeling stressed much of the day in 2018. That’s more than in all but three countries globally. Nearly half of Americans felt worried (45%) and more than a fifth (22%) felt angry. ‘Even as their economy roared, more Americas were stressed, angry and worried last year than they have been at many points during the last decade,’ Julie Ray, a Gallup editor, wrote in the summary report.” USA Today, April 26, 2019 “For me the relevant issue isn't what I report on the bottom line, it’s what I get to keep. … I love depreciation.” Donald Trump, The Art of the Deal 1. Introduction and overview: A debt-strapped era of downward mobility Those who praise the post-2008 economy as a successful recovery point to the fact that the stock market has soared to all-time highs, while the unemployment rate has fallen to a decade-low. But is the stock market a good proxy for how the overall economy is doing? The low reported unemployment rate sidesteps the predominance of minimum-wage jobs, part-time “gig” work, and the fact that the Federal Reserve’s Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. -

2016 Frederick County Affordable Housing Needs Assessment

FREDERICK COUNTY AFFORDABLE HOUSING NEEDS ASSESSMENT Frederick County, MD November 2016 520 NORTH MARKET STREET TANEY VILLAGE APARTMENTS VICTORIA PARK BELL COURT SENIOR LIVING TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………………….…1 Task 1: County Demographic Analysis...…………………………………………………………………....20 Task 2: Rental and Sales Price Trends …...………………………………….....................................................27 Task 3: Analysis of Residential Construction………………….…………………………………………….30 Task 4: Housing Affordability Analysis….………………...……..……...............................................................35 Task 5: Affordability Index….……………………………….......……...............................................................37 Task 6: Housing Gap Analysis……….…………………………………………………………………….44 Task 7: Housing Gap Trends……………………………………………………………………………….47 Task 8: Density Bonuses…..………………..……………………………………………………………….51 Task 9: MPDU Program Analysis…..……………………………………………………………………….52 Task 10: Homelessness Action Plan Summary……...……………………….………………………………54 Task 11: Meet with Representatives………..……...……………………….………………………………56 Task 12: Public Private Partnerships…..………...………………………………………………………….57 Task 13: Foreclosure Rates……….………………………………..……………………………………….58 Task 14: Housing Needs by Demographic Characteristics…………………….…………………………...60 Component 2.1.1: Inventory of Affordable and Accessible Housing………………………………………63 Component 2.1.2: Existing Affordable and Accessible Housing Market…….……………………………..64 Component 2.1.3: Location and Distribution of Affordable