The Cancer-Associated Meprin Β Variant G32R Provides An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovery and Optimization of Selective Inhibitors of Meprin Α (Part II)

pharmaceuticals Article Discovery and Optimization of Selective Inhibitors of Meprin α (Part II) Chao Wang 1,2, Juan Diez 3, Hajeung Park 1, Christoph Becker-Pauly 4 , Gregg B. Fields 5 , Timothy P. Spicer 1,6, Louis D. Scampavia 1,6, Dmitriy Minond 2,7 and Thomas D. Bannister 1,2,* 1 Department of Molecular Medicine, Scripps Research, Jupiter, FL 33458, USA; [email protected] (C.W.); [email protected] (H.P.); [email protected] (T.P.S.); [email protected] (L.D.S.) 2 Department of Chemistry, Scripps Research, Jupiter, FL 33458, USA; [email protected] 3 Rumbaugh-Goodwin Institute for Cancer Research, Nova Southeastern University, 3321 College Avenue, CCR r.605, Fort Lauderdale, FL 33314, USA; [email protected] 4 The Scripps Research Molecular Screening Center, Scripps Research, Jupiter, FL 33458, USA; [email protected] 5 Unit for Degradomics of the Protease Web, Institute of Biochemistry, University of Kiel, Rudolf-Höber-Str.1, 24118 Kiel, Germany; fi[email protected] 6 Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry and I-HEALTH, Florida Atlantic University, 5353 Parkside Drive, Jupiter, FL 33458, USA 7 Dr. Kiran C. Patel College of Allopathic Medicine, Nova Southeastern University, 3301 College Avenue, Fort Lauderdale, FL 33314, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Meprin α is a zinc metalloproteinase (metzincin) that has been implicated in multiple diseases, including fibrosis and cancers. It has proven difficult to find small molecules that are capable Citation: Wang, C.; Diez, J.; Park, H.; of selectively inhibiting meprin α, or its close relative meprin β, over numerous other metzincins Becker-Pauly, C.; Fields, G.B.; Spicer, which, if inhibited, would elicit unwanted effects. -

Structural Basis for the Sheddase Function of Human Meprin Β Metalloproteinase at the Plasma Membrane

Structural basis for the sheddase function of human meprin β metalloproteinase at the plasma membrane Joan L. Arolasa, Claudia Broderb, Tamara Jeffersonb, Tibisay Guevaraa, Erwin E. Sterchic, Wolfram Boded, Walter Stöckere, Christoph Becker-Paulyb, and F. Xavier Gomis-Rütha,1 aProteolysis Laboratory, Department of Structural Biology, Molecular Biology Institute of Barcelona, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas, Barcelona Science Park, E-08028 Barcelona, Spain; bInstitute of Biochemistry, Unit for Degradomics of the Protease Web, University of Kiel, D-24118 Kiel, Germany; cInstitute of Biochemistry and Molecular Medicine, University of Berne, CH-3012 Berne, Switzerland; dArbeitsgruppe Proteinaseforschung, Max-Planck-Institute für Biochemie, D-82152 Planegg-Martinsried, Germany; and eInstitute of Zoology, Cell and Matrix Biology, Johannes Gutenberg-University, D-55128 Mainz, Germany Edited by Brian W. Matthews, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, and approved August 22, 2012 (received for review June 29, 2012) Ectodomain shedding at the cell surface is a major mechanism to proteolysis” step within the membrane (1). This is the case for the regulate the extracellular and circulatory concentration or the processing of Notch ligand Delta1 and of APP, both carried out by activities of signaling proteins at the plasma membrane. Human γ-secretase after action of an α/β-secretase (11), and for signal- meprin β is a 145-kDa disulfide-linked homodimeric multidomain peptide peptidase, which removes remnants of the secretory pro- type-I membrane metallopeptidase that sheds membrane-bound tein translocation from the endoplasmic membrane (13). cytokines and growth factors, thereby contributing to inflammatory Recently, human meprin β (Mβ) was found to specifically pro- diseases, angiogenesis, and tumor progression. -

Transmembrane/Cytoplasmic, Rather Than Catalytic, Domains of Mmp14

RESEARCH ARTICLE 343 Development 140, 343-352 (2013) doi:10.1242/dev.084236 © 2013. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd Transmembrane/cytoplasmic, rather than catalytic, domains of Mmp14 signal to MAPK activation and mammary branching morphogenesis via binding to integrin 1 Hidetoshi Mori1,*, Alvin T. Lo1, Jamie L. Inman1, Jordi Alcaraz1,2, Cyrus M. Ghajar1, Joni D. Mott1, Celeste M. Nelson1,3, Connie S. Chen1, Hui Zhang1, Jamie L. Bascom1, Motoharu Seiki4 and Mina J. Bissell1,* SUMMARY Epithelial cell invasion through the extracellular matrix (ECM) is a crucial step in branching morphogenesis. The mechanisms by which the mammary epithelium integrates cues from the ECM with intracellular signaling in order to coordinate invasion through the stroma to make the mammary tree are poorly understood. Because the cell membrane-bound matrix metalloproteinase Mmp14 is known to play a key role in cancer cell invasion, we hypothesized that it could also be centrally involved in integrating signals for mammary epithelial cells (MECs) to navigate the collagen 1 (CL-1)-rich stroma of the mammary gland. Expression studies in nulliparous mice that carry a NLS-lacZ transgene downstream of the Mmp14 promoter revealed that Mmp14 is expressed in MECs at the tips of the branches. Using both mammary organoids and 3D organotypic cultures, we show that MMP activity is necessary for invasion through dense CL-1 (3 mg/ml) gels, but dispensable for MEC branching in sparse CL-1 (1 mg/ml) gels. Surprisingly, however, Mmp14 without its catalytic activity was still necessary for branching. Silencing Mmp14 prevented cell invasion through CL-1 and disrupted branching altogether; it also reduced integrin 1 (Itgb1) levels and attenuated MAPK signaling, disrupting Itgb1- dependent invasion/branching within CL-1 gels. -

Metalloproteases Meprin Α and Meprin Β Are C- and N-Procollagen Proteinases Important for Collagen Assembly and Tensile Strength

Metalloproteases meprin α and meprin β are C- and N-procollagen proteinases important for collagen assembly and tensile strength Claudia Brodera, Philipp Arnoldb, Sandrine Vadon-Le Goffc, Moritz A. Konerdingd, Kerstin Bahrd, Stefan Müllere, Christopher M. Overallf, Judith S. Bondg, Tomas Koudelkah, Andreas Tholeyh, David J. S. Hulmesc, Catherine Moalic, and Christoph Becker-Paulya,1 aUnit for Degradomics of the Protease Web, Institute of Biochemistry, University of Kiel, 24118 Kiel, Germany; bInstitute of Zoology, Johannes Gutenberg University, 55128 Mainz, Germany; cTissue Biology and Therapeutic Engineering Unit, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique/University of Lyon, Unité Mixte de Recherche 5305, Unité Mixte de Service 3444 Biosciences Gerland-Lyon Sud, 69367 Lyon Cedex 7, France; dInstitute of Functional and Clinical Anatomy, University Medical Center, Johannes Gutenberg University, 55128 Mainz, Germany; eDepartment of Gastroenterology, University of Bern, CH-3010 Bern, Switzerland; fCentre for Blood Research, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z3; gDepartment of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine, Hershey, PA 17033; and hInstitute of Experimental Medicine, University of Kiel, 24118 Kiel, Germany Edited by Robert Huber, Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, Planegg-Martinsried, Germany, and approved July 9, 2013 (received for review March 22, 2013) Type I fibrillar collagen is the most abundant protein in the human formation (22). A tight balance between synthesis and break- body, crucial for the formation and strength of bones, skin, and down of ECM is required for the function of all tissues, and tendon. Proteolytic enzymes are essential for initiation of the dysregulation leads to pathophysiological events, such as arthri- assembly of collagen fibrils by cleaving off the propeptides. -

The Positive Side of Proteolysis in Alzheimer's Disease

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Biochemistry Research International Volume 2011, Article ID 721463, 13 pages doi:10.1155/2011/721463 Review Article Zinc Metalloproteinases and Amyloid Beta-Peptide Metabolism: The Positive Side of Proteolysis in Alzheimer’s Disease Mallory Gough, Catherine Parr-Sturgess, and Edward Parkin Division of Biomedical and Life Sciences, School of Health and Medicine, Lancaster University, Lancaster LA1 4YQ, UK Correspondence should be addressed to Edward Parkin, [email protected] Received 17 August 2010; Accepted 7 September 2010 Academic Editor: Simon J. Morley Copyright © 2011 Mallory Gough et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Alzheimer’s disease is a neurodegenerative condition characterized by an accumulation of toxic amyloid beta- (Aβ-)peptides in the brain causing progressive neuronal death. Aβ-peptides are produced by aspartyl proteinase-mediated cleavage of the larger amyloid precursor protein (APP). In contrast to this detrimental “amyloidogenic” form of proteolysis, a range of zinc metalloproteinases can process APP via an alternative “nonamyloidogenic” pathway in which the protein is cleaved within its Aβ region thereby precluding the formation of intact Aβ-peptides. In addition, other members of the zinc metalloproteinase family can degrade preformed Aβ-peptides. As such, the zinc metalloproteinases, collectively, are key to downregulating Aβ generation and enhancing its degradation. It is the role of zinc metalloproteinases in this “positive side of proteolysis in Alzheimer’s disease” that is discussed in the current paper. 1. Introduction of 38–43 amino acid peptides called amyloid beta (Aβ)- peptides. -

Secretion of Matrix Metalloproteinases and Their

[CANCER RESEARCH 53, 4493-4498, October 1, 1993] Secretion of Matrix Metalloproteinases and Their Inhibitors (Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases) by Human Prostate in Explant Cultures: Reduced Tissue Inhibitor of Metailoproteinase Secretion by Malignant Tissues 1 Balakrishna L. Lokeshwar, 2 Marie G. Seizer, Norman L. Block, and Zeenat Gunja-Smith Departments of Urology [B. L. L., M. G. S., N. L. B.] and Medicine [Z. G-S.], University of Miami School of Medicine, Miami, Florida 33101 ABSTRACT V, and IX, as well as the noncollagenous components of the extracel- lular matrix, including laminin and fibronectin (6). In addition, Unregulated secretion of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) or their MMP-3 is also known to activate procollagenases (7). Increased levels endogenous protein inhibitors (tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases, of these proteinases have been implicated with the invasive potential TIMPs) has been implicated in tumor invasion and metastasis. Species of MMPs and TIMPs secreted by epithelial cultures of normal, benign, and of tumors (8-10). malignant prostate were identified and their levels were compared. Frag- Matrixins secreted by normal cells are proenzymes (zymogens) and ments of fresh tissue were cultured in a serum-free medium that supported are inactive (11). This is due to a highly conserved sequence of nine the outgrowth of prostatic epithelial cells. Biochemical analysis of the amino acid residues in the propeptide region containing a solitary conditioned media by gelatin zymography and enzyme assays showed that cysteine residue bound to the metal ion, Zn 2+, at the active center both normal and neoplastic tissues secreted latent and active forms of both (12). -

Self-Organization of Engineered Epithelial Tubules by Differential Cellular Motility

Self-organization of engineered epithelial tubules by differential cellular motility Hidetoshi Moria,1, Nikolce Gjorevskib,1, Jamie L. Inmana,1, Mina J. Bissella,2, and Celeste M. Nelsonb,2 aLife Sciences Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720; and bDepartments of Chemical Engineering and Molecular Biology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544 Edited by Kenneth Yamada, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, and accepted by the Editorial Board July 16, 2009 (received for review February 4, 2009) Patterning of developing tissues arises from a number of mecha- also in many epithelial tumors, including those from breast, lung, nisms, including cell shape change, cell proliferation, and cell sorting and colon (17–19), and confers cancer cells with the pernicious from differential cohesion or tension. Here, we reveal that differences ability to degrade and penetrate the basement membrane and in cell motility can also lead to cell sorting within tissues. Using mosaic metastasize to distant sites (20–23). Intriguingly, cells at the invasive engineered mammary epithelial tubules, we found that cells sorted front of metastatic cohorts express the highest levels of MMP14 (24, depending on their expression level of the membrane-anchored 25). Understanding how the expression pattern of this protease is collagenase matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-14. These rearrange- determined will likely yield insights into possible mechanisms of ments were independent of the catalytic activity of MMP14 but cancer progression and invasion. absolutely required the hemopexin domain. We describe a signaling Here we present evidence to suggest that cellular rearrange- cascade downstream of MMP14 through Rho kinase that allows cells ments generated by differential cellular motility determine the to sort within the model tissues. -

Zinc Metalloproteinases and Amyloid Beta-Peptide Metabolism: the Positive Side of Proteolysis in Alzheimer’S Disease

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Biochemistry Research International Volume 2011, Article ID 721463, 13 pages doi:10.1155/2011/721463 Review Article Zinc Metalloproteinases and Amyloid Beta-Peptide Metabolism: The Positive Side of Proteolysis in Alzheimer’s Disease Mallory Gough, Catherine Parr-Sturgess, and Edward Parkin Division of Biomedical and Life Sciences, School of Health and Medicine, Lancaster University, Lancaster LA1 4YQ, UK Correspondence should be addressed to Edward Parkin, [email protected] Received 17 August 2010; Accepted 7 September 2010 Academic Editor: Simon J. Morley Copyright © 2011 Mallory Gough et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Alzheimer’s disease is a neurodegenerative condition characterized by an accumulation of toxic amyloid beta- (Aβ-)peptides in the brain causing progressive neuronal death. Aβ-peptides are produced by aspartyl proteinase-mediated cleavage of the larger amyloid precursor protein (APP). In contrast to this detrimental “amyloidogenic” form of proteolysis, a range of zinc metalloproteinases can process APP via an alternative “nonamyloidogenic” pathway in which the protein is cleaved within its Aβ region thereby precluding the formation of intact Aβ-peptides. In addition, other members of the zinc metalloproteinase family can degrade preformed Aβ-peptides. As such, the zinc metalloproteinases, collectively, are key to downregulating Aβ generation and enhancing its degradation. It is the role of zinc metalloproteinases in this “positive side of proteolysis in Alzheimer’s disease” that is discussed in the current paper. 1. Introduction of 38–43 amino acid peptides called amyloid beta (Aβ)- peptides. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2003/0082511 A1 Brown Et Al

US 20030082511A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2003/0082511 A1 Brown et al. (43) Pub. Date: May 1, 2003 (54) IDENTIFICATION OF MODULATORY Publication Classification MOLECULES USING INDUCIBLE PROMOTERS (51) Int. Cl." ............................... C12O 1/00; C12O 1/68 (52) U.S. Cl. ..................................................... 435/4; 435/6 (76) Inventors: Steven J. Brown, San Diego, CA (US); Damien J. Dunnington, San Diego, CA (US); Imran Clark, San Diego, CA (57) ABSTRACT (US) Correspondence Address: Methods for identifying an ion channel modulator, a target David B. Waller & Associates membrane receptor modulator molecule, and other modula 5677 Oberlin Drive tory molecules are disclosed, as well as cells and vectors for Suit 214 use in those methods. A polynucleotide encoding target is San Diego, CA 92121 (US) provided in a cell under control of an inducible promoter, and candidate modulatory molecules are contacted with the (21) Appl. No.: 09/965,201 cell after induction of the promoter to ascertain whether a change in a measurable physiological parameter occurs as a (22) Filed: Sep. 25, 2001 result of the candidate modulatory molecule. Patent Application Publication May 1, 2003 Sheet 1 of 8 US 2003/0082511 A1 KCNC1 cDNA F.G. 1 Patent Application Publication May 1, 2003 Sheet 2 of 8 US 2003/0082511 A1 49 - -9 G C EH H EH N t R M h so as se W M M MP N FIG.2 Patent Application Publication May 1, 2003 Sheet 3 of 8 US 2003/0082511 A1 FG. 3 Patent Application Publication May 1, 2003 Sheet 4 of 8 US 2003/0082511 A1 KCNC1 ITREXCHO KC 150 mM KC 2000000 so 100 mM induced Uninduced Steady state O 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 Time (seconds) FIG. -

Polymorphisms of the Matrix Metalloproteinase Genes

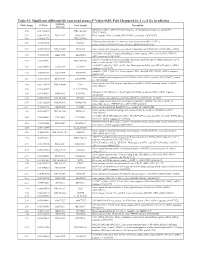

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Polymorphisms of the matrix metalloproteinase genes are associated with essential hypertension in a Caucasian population of Central Russia Maria Moskalenko1, Irina Ponomarenko1, Evgeny Reshetnikov1*, Volodymyr Dvornyk2 & Mikhail Churnosov1 This study aimed to determine possible association of eight polymorphisms of seven MMP genes with essential hypertension (EH) in a Caucasian population of Central Russia. Eight SNPs of the MMP1, MMP2, MMP3, MMP7, MMP8, MMP9, and MMP12 genes and their gene–gene (epistatic) interactions were analyzed for association with EH in a cohort of 939 patients and 466 controls using logistic regression and assuming additive, recessive, and dominant genetic models. The functional signifcance of the polymorphisms associated with EH and 114 variants linked to them (r2 ≥ 0.8) was analyzed in silico. Allele G of rs11568818 MMP7 was associated with EH according to all three genetic models (OR = 0.58–0.70, pperm = 0.01–0.03). The above eight SNPs were associated with the disorder within 12 most signifcant epistatic models (OR = 1.49–1.93, pperm < 0.02). Loci rs1320632 MMP8 and rs11568818 MMP7 contributed to the largest number of the models (12 and 10, respectively). The EH-associated loci and 114 SNPs linked to them had non-synonymous, regulatory, and eQTL signifcance for 15 genes, which contributed to the pathways related to metalloendopeptidase activity, collagen degradation, and extracellular matrix disassembly. In summary, eight studied SNPs of MMPs genes were associated with EH in the Caucasian population of Central Russia. Cardiovascular diseases are a global problem of modern healthcare and the second most common cause of total mortality1,2. -

(P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 Vs. 0 Gy Irradiation

Table S1: Significant differentially expressed genes (P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 vs. 0 Gy irradiation Genbank Fold Change P -Value Gene Symbol Description Accession Q9F8M7_CARHY (Q9F8M7) DTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase (Fragment), partial (9%) 6.70 0.017399678 THC2699065 [THC2719287] 5.53 0.003379195 BC013657 BC013657 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:4152983, partial cds. [BC013657] 5.10 0.024641735 THC2750781 Ciliary dynein heavy chain 5 (Axonemal beta dynein heavy chain 5) (HL1). 4.07 0.04353262 DNAH5 [Source:Uniprot/SWISSPROT;Acc:Q8TE73] [ENST00000382416] 3.81 0.002855909 NM_145263 SPATA18 Homo sapiens spermatogenesis associated 18 homolog (rat) (SPATA18), mRNA [NM_145263] AA418814 zw01a02.s1 Soares_NhHMPu_S1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:767978 3', 3.69 0.03203913 AA418814 AA418814 mRNA sequence [AA418814] AL356953 leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 6 {Homo sapiens} (exp=0; 3.63 0.0277936 THC2705989 wgp=1; cg=0), partial (4%) [THC2752981] AA484677 ne64a07.s1 NCI_CGAP_Alv1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:909012, mRNA 3.63 0.027098073 AA484677 AA484677 sequence [AA484677] oe06h09.s1 NCI_CGAP_Ov2 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:1385153, mRNA sequence 3.48 0.04468495 AA837799 AA837799 [AA837799] Homo sapiens hypothetical protein LOC340109, mRNA (cDNA clone IMAGE:5578073), partial 3.27 0.031178378 BC039509 LOC643401 cds. [BC039509] Homo sapiens Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6) (FAS), transcript variant 1, mRNA 3.24 0.022156298 NM_000043 FAS [NM_000043] 3.20 0.021043295 A_32_P125056 BF803942 CM2-CI0135-021100-477-g08 CI0135 Homo sapiens cDNA, mRNA sequence 3.04 0.043389246 BF803942 BF803942 [BF803942] 3.03 0.002430239 NM_015920 RPS27L Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S27-like (RPS27L), mRNA [NM_015920] Homo sapiens tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10c, decoy without an 2.98 0.021202829 NM_003841 TNFRSF10C intracellular domain (TNFRSF10C), mRNA [NM_003841] 2.97 0.03243901 AB002384 C6orf32 Homo sapiens mRNA for KIAA0386 gene, partial cds. -

Appendix 2. Significantly Differentially Regulated Genes in Term Compared with Second Trimester Amniotic Fluid Supernatant

Appendix 2. Significantly Differentially Regulated Genes in Term Compared With Second Trimester Amniotic Fluid Supernatant Fold Change in term vs second trimester Amniotic Affymetrix Duplicate Fluid Probe ID probes Symbol Entrez Gene Name 1019.9 217059_at D MUC7 mucin 7, secreted 424.5 211735_x_at D SFTPC surfactant protein C 416.2 206835_at STATH statherin 363.4 214387_x_at D SFTPC surfactant protein C 295.5 205982_x_at D SFTPC surfactant protein C 288.7 1553454_at RPTN repetin solute carrier family 34 (sodium 251.3 204124_at SLC34A2 phosphate), member 2 238.9 206786_at HTN3 histatin 3 161.5 220191_at GKN1 gastrokine 1 152.7 223678_s_at D SFTPA2 surfactant protein A2 130.9 207430_s_at D MSMB microseminoprotein, beta- 99.0 214199_at SFTPD surfactant protein D major histocompatibility complex, class II, 96.5 210982_s_at D HLA-DRA DR alpha 96.5 221133_s_at D CLDN18 claudin 18 94.4 238222_at GKN2 gastrokine 2 93.7 1557961_s_at D LOC100127983 uncharacterized LOC100127983 93.1 229584_at LRRK2 leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 HOXD cluster antisense RNA 1 (non- 88.6 242042_s_at D HOXD-AS1 protein coding) 86.0 205569_at LAMP3 lysosomal-associated membrane protein 3 85.4 232698_at BPIFB2 BPI fold containing family B, member 2 84.4 205979_at SCGB2A1 secretoglobin, family 2A, member 1 84.3 230469_at RTKN2 rhotekin 2 82.2 204130_at HSD11B2 hydroxysteroid (11-beta) dehydrogenase 2 81.9 222242_s_at KLK5 kallikrein-related peptidase 5 77.0 237281_at AKAP14 A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein 14 76.7 1553602_at MUCL1 mucin-like 1 76.3 216359_at D MUC7 mucin 7,