University of Oklahoma Graduate College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corpora and (The Need For) Other Methods in a Study of Lancashire Dialect

ZAA 54.1 (2006): s1-sn © WILLEM HOLLMANN AND ANNA SIEWIERSKA Corpora and (the need for) other methods in a study of Lancashire dialect Abstract: This paper is based on a nascent project on Lancashire dialect grammar, which aims to describe the relevant features of this dialect and to engage with related theoretical and methodological debates. We show how corpora allow one to arrive at more precise descriptions of the data than was previously possible. But we also draw attention to the need for other methods, in particular modern elicitation tasks and attitude questionnaires developed in perceptual dialectology. Combining these methods promises to provide more insight into both more general theoretical issues and the exact nature of the object of study, namely Lancashire dialect. 1. Introduction This paper describes a nascent project on the grammar of Lancashire dialect. In line with the theme of this issue we focus on methodological issues, in particular matters concerning the use of corpora, both advantages and challenges. Section 2 presents some background information about the aims of the project, situating it within the recent surge in interest in dialect grammar. Section 3 offers an illustration of the in- sights that may be obtained from using corpora as well as the limitations of corpus studies, with reference to three ditransitive constructions. Section 4 shifts the stage to two other variables we have started to analyse, namely agreement in past tense BE and the presence, reduction or omission of the definite article. We will argue for the use of an additional data collection method, viz. modern elicitation tasks (cf. -

11Eyes Achannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air

11eyes AChannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air Master Amaenaideyo Angel Beats Angelic Layer Another Ao No Exorcist Appleseed XIII Aquarion Arakawa Under The Bridge Argento Soma Asobi no Iku yo Astarotte no Omocha Asu no Yoichi Asura Cryin' B Gata H Kei Baka to Test Bakemonogatari (and sequels) Baki the Grappler Bakugan Bamboo Blade Banner of Stars Basquash BASToF Syndrome Battle Girls: Time Paradox Beelzebub BenTo Betterman Big O Binbougami ga Black Blood Brothers Black Cat Black Lagoon Blassreiter Blood Lad Blood+ Bludgeoning Angel Dokurochan Blue Drop Bobobo Boku wa Tomodachi Sukunai Brave 10 Btooom Burst Angel Busou Renkin Busou Shinki C3 Campione Cardfight Vanguard Casshern Sins Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Chaos;Head Chobits Chrome Shelled Regios Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai Clannad Claymore Code Geass Cowboy Bebop Coyote Ragtime Show Cuticle Tantei Inaba DFrag Dakara Boku wa, H ga Dekinai Dan Doh Dance in the Vampire Bund Danganronpa Danshi Koukousei no Nichijou Daphne in the Brilliant Blue Darker Than Black Date A Live Deadman Wonderland DearS Death Note Dennou Coil Denpa Onna to Seishun Otoko Densetsu no Yuusha no Densetsu Desert Punk Detroit Metal City Devil May Cry Devil Survivor 2 Diabolik Lovers Disgaea Dna2 Dokkoida Dog Days Dororon EnmaKun Meeramera Ebiten Eden of the East Elemental Gelade Elfen Lied Eureka 7 Eureka 7 AO Excel Saga Eyeshield 21 Fight Ippatsu! JuudenChan Fooly Cooly Fruits Basket Full Metal Alchemist Full Metal Panic Futari Milky Holmes GaRei Zero Gatchaman Crowds Genshiken Getbackers Ghost -

Perceptual Dialectology and GIS in Kurdish 1

Perceptual Dialectology and GIS in Kurdish 1 Full title: A perceptual dialectological approach to linguistic variation and spatial analysis of Kurdish varieties Main Author: Eva Eppler, PhD, RCSLT, Mag. Phil Reader/Associate Professor in Linguistics Department of Media, Culture and Language University of Roehampton | London | SW15 5SL [email protected] | www.roehampton.ac.uk Tel: +44 (0) 20 8392 3791 Co-author: Josef Benedikt, PhD, Mag.rer.nat. Independent Scholar, Senior GIS Researcher GeoLogic Dr. Benedikt Roegergasse 11/18 1090 Vienna, Austria [email protected] | www.geologic.at Short Title: Perceptual Dialectology and GIS in Kurdish Perceptual Dialectology and GIS in Kurdish 2 Abstract: This paper presents results of a first investigation into Kurdish linguistic varieties and their spatial distribution. Kurdish dialects are used across five nation states in the Middle East and only one, Sorani, has official status in one of them. The study employs the ‘draw-a-map task’ established in Perceptual Dialectology; the analysis is supported by Geographical Information Systems (GIS). The results show that, despite the geolinguistic and geopolitical situation, Kurdish respondents have good knowledge of the main varieties of their language (Kurmanji, Sorani and the related variety Zazaki) and where to localize them. Awareness of the more diverse Southern Kurdish varieties is less definitive. This indicates that the Kurdish language plays a role in identity formation, but also that smaller isolated varieties are not only endangered in terms of speakers, but also in terms of their representations in Kurds’ mental maps of the linguistic landscape they live in. Acknowledgments: This work was supported by a Santander and by Ede & Ravenscroft Research grant 2016. -

Dialect Perception and Attitudes to Variation Dennis R. Preston Department of Linguistics, German, Slavic, Asian, and African La

Dialect Perception and Attitudes to Variation Dennis R. Preston Department of Linguistics, German, Slavic, Asian, and African Languages Gregory C. Robinson Department of Audiology and Speech Sciences Michigan State University East Lansing, MI 48824, USA [email protected] [email protected] I. Language and People It is perhaps the least surprising thing imaginable to find that attitudes towards languages and their varieties seem to be tied to attitudes towards groups of people. Some groups are believed to be decent, hard-working, and intelligent (and so is their language or variety); some groups are believed to be laid-back, romantic, and devil-may-care (and so is their language or variety); some groups are believed to be lazy, insolent, and procrastinating (and so is their language or variety); some groups are believed to be hard-nosed, aloof, and unsympathetic (and so is their language or variety), and so on. For the folk mind, such correlations are obvious, reaching down even into the linguistic details of the language or variety itself. Germans are harsh; just listen to their harsh, gutteral consonants. US Southerners are laid-back and lazy; just listen to their lazy, drawled vowels. Lower-status speakers are unintelligent; they don’t even understand that two negatives make a positive, and so on. Edwards summarizes this correlation for many social psychologists when he notes that ‘ … people’s reactions to language varieties reveal much of their perception of the speakers of these varieties’ (1982:20). In the clinical fields of speech-language pathology and audiology, these perceptions can have major implications. Negative attitudes about the individuals who use certain linguistic features can pervade service delivery causing testing bias, overrepresentation of minorities and nonmainstream dialect speakers in special education, and lack of linguistic confidence in children. -

Perceptual Dialectology of Egypt. a View from the Berber-Speaking Periphery

Catherine Miller, Alexandrine Barontini, Marie-Aimée Germanos, Jairo Guerrero and Christophe Pereira (dir.) Studies on Arabic Dialectology and Sociolinguistics Proceedings of the 12th International Conference of AIDA held in Marseille from May 30th to June 2nd 2017 Institut de recherches et d’études sur les mondes arabes et musulmans Perceptual Dialectology of Egypt. A View from the Berber-Speaking Periphery Valentina Serreli DOI: 10.4000/books.iremam.5026 Publisher: Institut de recherches et d’études sur les mondes arabes et musulmans Place of publication: Aix-en-Provence Year of publication: 2019 Published on OpenEdition Books: 24 January 2019 Serie: Livres de l’IREMAM Electronic ISBN: 9791036533891 http://books.openedition.org Electronic reference SERRELI, Valentina. Perceptual Dialectology of Egypt. A View from the Berber-Speaking Periphery In: Studies on Arabic Dialectology and Sociolinguistics: Proceedings of the 12th International Conference of AIDA held in Marseille from May 30th to June 2nd 2017 [online]. Aix-en-Provence: Institut de recherches et d’études sur les mondes arabes et musulmans, 2019 (generated 12 janvier 2021). Available on the Internet: <http://books.openedition.org/iremam/5026>. ISBN: 9791036533891. DOI: https://doi.org/ 10.4000/books.iremam.5026. This text was automatically generated on 12 January 2021. Perceptual Dialectology of Egypt. A View from the Berber-Speaking Periphery 1 Perceptual Dialectology of Egypt. A View from the Berber-Speaking Periphery Valentina Serreli 1. Introduction 1 Drawing on an attitudinal and perceptual dialectological survey, the paper presents the dialectology of Egypt, according to the perception of high school students from Siwa Oasis, a peripheral and non-native Arabic-speaking region of Egypt. -

The Apology | the B-Side | Night School | Madonna: Rebel Heart Tour | Betting on Zero Scene & Heard

November-December 2017 VOL. 32 THE VIDEO REVIEW MAGAZINE FOR LIBRARIES N O . 6 IN THIS ISSUE One Week and a Day | Poverty, Inc. | The Apology | The B-Side | Night School | Madonna: Rebel Heart Tour | Betting on Zero scene & heard BAKER & TAYLOR’S SPECIALIZED A/V TEAM OFFERS ALL THE PRODUCTS, SERVICES AND EXPERTISE TO FULFILL YOUR LIBRARY PATRONS’ NEEDS. Learn more about Baker & Taylor’s Scene & Heard team: ELITE Helpful personnel focused exclusively on A/V products and customized services to meet continued patron demand PROFICIENT Qualified entertainment content buyers ensure frontlist and backlist titles are available and delivered on time SKILLED Supportive Sales Representatives with an average of 15 years industry experience DEVOTED Nationwide team of A/V processing staff ready to prepare your movie and music products to your shelf-ready specifications Experience KNOWLEDGEABLE Baker & Taylor is the Full-time staff of A/V catalogers, most experienced in the backed by their MLS degree and more than 43 years of media cataloging business; selling A/V expertise products to libraries since 1986. 800-775-2600 x2050 [email protected] www.baker-taylor.com Spotlight Review One Week and a Day and target houses that are likely to be empty while mourners are out. Eyal also goes to the HHH1/2 hospice where Ronnie died (and retrieves his Oscilloscope, 98 min., in Hebrew w/English son’s medical marijuana, prompting a later subtitles, not rated, DVD: scene in which he struggles to roll a joint for Publisher/Editor: Randy Pitman $34.99, Blu-ray: $39.99 the first time in his life), gets into a conflict Associate Editor: Jazza Williams-Wood Wr i t e r- d i r e c t o r with a taxi driver, and tries (unsuccessfully) to hide in the bushes when his neighbors show Editorial Assistant: Christopher Pitman Asaph Polonsky’s One Week and a Day is a up with a salad. -

Aachi Wa Ssipak Afro Samurai Afro Samurai Resurrection Air Air Gear

1001 Nights Burn Up! Excess Dragon Ball Z Movies 3 Busou Renkin Druaga no Tou: the Aegis of Uruk Byousoku 5 Centimeter Druaga no Tou: the Sword of Uruk AA! Megami-sama (2005) Durarara!! Aachi wa Ssipak Dwaejiui Wang Afro Samurai C Afro Samurai Resurrection Canaan Air Card Captor Sakura Edens Bowy Air Gear Casshern Sins El Cazador de la Bruja Akira Chaos;Head Elfen Lied Angel Beats! Chihayafuru Erementar Gerad Animatrix, The Chii's Sweet Home Evangelion Ano Natsu de Matteru Chii's Sweet Home: Atarashii Evangelion Shin Gekijouban: Ha Ao no Exorcist O'uchi Evangelion Shin Gekijouban: Jo Appleseed +(2004) Chobits Appleseed Saga Ex Machina Choujuushin Gravion Argento Soma Choujuushin Gravion Zwei Fate/Stay Night Aria the Animation Chrno Crusade Fate/Stay Night: Unlimited Blade Asobi ni Iku yo! +Ova Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai! Works Ayakashi: Samurai Horror Tales Clannad Figure 17: Tsubasa & Hikaru Azumanga Daioh Clannad After Story Final Fantasy Claymore Final Fantasy Unlimited Code Geass Hangyaku no Lelouch Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children B Gata H Kei Code Geass Hangyaku no Lelouch Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within Baccano! R2 Freedom Baka to Test to Shoukanjuu Colorful Fruits Basket Bakemonogatari Cossette no Shouzou Full Metal Panic! Bakuman. Cowboy Bebop Full Metal Panic? Fumoffu + TSR Bakumatsu Kikansetsu Coyote Ragtime Show Furi Kuri Irohanihoheto Cyber City Oedo 808 Fushigi Yuugi Bakuretsu Tenshi +Ova Bamboo Blade Bartender D.Gray-man Gad Guard Basilisk: Kouga Ninpou Chou D.N. Angel Gakuen Mokushiroku: High School Beck Dance in -

87 LANGUAGE, PEOPLE, SALIENCE, SPACE: PERCEPTUAL DIALECTOLOGY and LANGUAGE REGARD Dennis R. Preston Oklahoma State University, U

Dialectologia 5 (2010), 87-131. LANGUAGE, PEOPLE, SALIENCE, SPACE: PERCEPTUAL DIALECTOLOGY AND LANGUAGE REGARD Dennis R. Preston Oklahoma State University, USA [email protected] Abstract This paper explores the not novel idea that popular notions of the geographical distribution and status of linguistic facts are related to beliefs about the speakers of regional varieties but goes on to develop an approach to the underlying cognitive mechanisms that are employed when such connections are made. A detailed procedural account of the awakening of a response, called one of language regard , is given, as well as a structural account of an underlying attitudinal cognitorium with regard to popular beliefs about United States’ Southerners. A number of studies illustrating a variety of research tools in determining the connections, the response mechanisms, and the underlying structures of belief are provided. Keywords language regard, language attitudes, attitudinal cognitorium, perceptual dialectology, implicit and explicit attitudes 1. Introduction It is important to people whose major interest is in language variation to know where the land lies and how it is shaped and filled up — the facts of physical geography — because such matters have an influence on language. Sarah Thomason notes, for example, that Swahili will probably borrow no linguistic features from Pirahã (2001: 78) because speakers of the two languages are widely separated geographically and unlikely to run into one another. Introductory linguistics commonplaces about blocking (mountains, rivers, etc.) and facilitating (passes, rivers, etc.) geographical elements with regard to language and variety contact are also well known. There has even been suspicion that physical facts about geography are directly, even causally, related to 87 ©Universitat de Barcelona Dennis R. -

Engaged in Translation: Fandom Production in the Latin America's Anime Community of Syncrajo

Engaged in Translation: Fandom Production in The Latin America’s Anime Community of Syncrajo. MKVM13: Media and Communication Studies: Master’s Thesis. 2021 Faculty of Social Science, Lund University Author – Emilio González González Pliego Supervisor: Tobias Linne Examiner: Annette Hill [email protected] Word Count (21,187) Abstract Fansub (Fan-subtitled) is the term coined after the action of subtitling a foreign audio-visual production. Fansubs started being studied after the phenomenon started gaining popularity within communities of anime fans. That used them as a way of access to the products they desire to consume. Creating different opinions that range as a way of going against the “top- down corporate-driven process (using) a bottom-up consumer-driven process” (Jenkins, 2004, p.37) to remarks against their legality, as they modify and distribute a copyrighted work for free. The majority of the studies made around fansub culture revolve around the experience of anime, and until recently started researching different kinds of media, like videogames, news videos, webpages and more. Even with the existence of these studies, few researchers focus on the motifs of the fansubbers (fans that do subtitles) to start doing them. This thesis will focus on studying how the members of these groups get engaged with a product to start doing free labour using the theory of Spectrum of engagement of Hill (2019). Also interesting to this thesis. Will be the idea of appropriation to understand if the fansub does something beyond the translation to take ownership of the product fansubs re-distribute. In the last years, there has been a decrease of active fansubs, as new legal and accessible ways to get the content had been made available. -

The Dynamics Between Unified Basque & Dialects in the Northern

International Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 6, No. 1, March 2019 doi:10.30845/ijll.v6n1p13 The Dynamics between Unified Basque & Dialects in the Northern Basque Country: A Survey Based on Perceptual Dialectology Jean-Baptiste Coyos Basque Text & Language Study Center IKER - UMR 5478 (Bayonne - France) & Royal Academy of the Basque Language Château Neuf - Place Paul Bert 64100 Bayonne France Abstract Today Unified Basque, a standardised written version of Basque created by the Academy of the Basque Language from the 1960s onwards and which is now widely codified, coexists alongside the Northern Basque Country’s dialects (NBC, France). Understanding the relationship between these different forms of the Basque language is necessary in order to implement an appropriate language policy. In this paper we present the answers to the open-ended questions of a survey and accompanying comments. Based on Perceptual Dialectology, the questionnaire was completed by 40 people working in Basque in the NBC: writers, teachers, journalists, translators and language technicians. The main objective was to gather their opinions regarding Unified Basque and the dialects. The respondents were chosen according to the following criterion: they are all language prescribers, working in the language and providing a model of the Basque language for society.The main results of the survey are as follows: 95% of respondents think that Unified Basque is necessary in the NBC, 92.5% believe that the specificities of the NBC’s linguistic varieties should be preserved, 80% that Unified Basque does not harm the NBC’s dialects and more than half that there is now a form of Unified Basque specific to the NBC. -

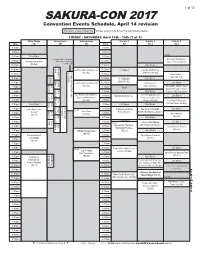

Sakura-Con 2017

1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2017 Convention Events Schedule, April 14 revision FRIDAY - SATURDAY, April 14th - 15th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, April 14th - 15th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, April 14th - 15th (4 of 4) Panels 4 Panels 5 Panels 6 Panels 7 Panels 8 Panels 9 Workshop Arts & Crafts Model Karaoke Console Gaming Theater 1 Theater 2 Theater 3 Theater 4 Anime Music Video Seattle Go Mahjong Mahjong Miniatures Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 4C-4 401 4C-1 Time 3AB Skagit 2 Skagit 3 Time Time Chelan 4 Chelan 2 Building: 214 307-308 606-609 Time 616-617 618-619 615 620 Theater: 6A Center: 305 310 Theater: 309 Time Gaming: 614 613 Gaming: 612 Time 7:00am 7:00am 7:00am 7:00am 7:00am 7:00am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, April 14th - 15th (1 of 4) 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Main Stage Autographs Sakuradome Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Time 4A 4B 6E Time 6C 4C-2 4C-3 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am Mask Making 8:00am Irie, Mignogna, Glass, Crunchyroll Theater Block: Shiki Douji showcase: Someday’s Dreamers II: 8:00am 8:00am (8:45) Workshop Sabat showcase: 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am elDLIVE 1-4 Full Metal Panic! Sora 1-41-6 8:30am 8:30am (SC-ALL) Fullmetal Alchemist: (SC-13, sub) 1-8 (SC-10, sub) Let's Play Meetup (SC-13) Brotherhood 1-81-4 Relic Knights 2.0 Anki Overdrive & Miniatures Freeplay 9:00am 9:00am Setup 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am Open Karaoke 9:00am (SC-13, dub) AMV Showcase 9:00am 9:00am (SC-13, dub) (9:45) (9:45) (SC-ALL) 9:30am Doors -

Three Regional Dialects in Turkey

International Journal of Language and Linguistics 2015; 3(6): 436-439 Published online December 14, 2015 (http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ijll) doi: 10.11648/j.ijll.20150306.27 ISSN: 2330-0205 (Print); ISSN: 2330-0221 (Online) Three Regional Dialects in Turkey Meryem Karlık, Azamat Akbarov Department of Foreign Languages and Literature, International Burch University, Sarajevo, Bosnia & Herzegovina Email address: [email protected] (M. Karlık), [email protected] (A. Akbarov) To cite this article: Meryem Karlık, Azamat Akbarov. Three Regional Dialects in Turkey. International Journal of Language and Linguistics . Vol. 3, No. 6, 2015, pp. 436-439. doi: 10.11648/j.ijll.20150306.27 Abstract: The purpose of this article is to show whether Konya, Çanakkale and Manisa dialects have a diglosic feature or not and how the usage of the components of diglossia is seen in these cities. In order to determine High or Low varieties of the Turkish Language, these three dialects are compared to Istanbul dialects. These cities are different part of Turkey and every of them have migration from other cities. So people are using Low variety in their daily lives even they are supposed to use High variety of Turkish Language when it is a necessity. However, they have communication problems in their conversations in both High and Low variety forms of Turkish Language. We explain similarities and differences between these three dialects comparing with Istanbul dialects via given examples and tables. How people are using the language and even one word cannot be similar to other dialect is shown. Moreover comparing words and verbs with their meanings which are changing in some situations completely would be beneficial in order to understand the diglossic issues in Turkish Language.