Cervical Cancer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

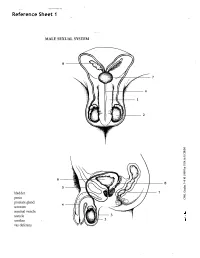

Reference Sheet 1

MALE SEXUAL SYSTEM 8 7 8 OJ 7 .£l"00\.....• ;:; ::>0\~ <Il '"~IQ)I"->. ~cru::>s ~ 6 5 bladder penis prostate gland 4 scrotum seminal vesicle testicle urethra vas deferens FEMALE SEXUAL SYSTEM 2 1 8 " \ 5 ... - ... j 4 labia \ ""\ bladderFallopian"k. "'"f"";".'''¥'&.tube\'WIT / I cervixt r r' \ \ clitorisurethrauterus 7 \ ~~ ;~f4f~ ~:iJ 3 ovaryvagina / ~ 2 / \ \\"- 9 6 adapted from F.L.A.S.H. Reproductive System Reference Sheet 3: GLOSSARY Anus – The opening in the buttocks from which bowel movements come when a person goes to the bathroom. It is part of the digestive system; it gets rid of body wastes. Buttocks – The medical word for a person’s “bottom” or “rear end.” Cervix – The opening of the uterus into the vagina. Circumcision – An operation to remove the foreskin from the penis. Cowper’s Glands – Glands on either side of the urethra that make a discharge which lines the urethra when a man gets an erection, making it less acid-like to protect the sperm. Clitoris – The part of the female genitals that’s full of nerves and becomes erect. It has a glans and a shaft like the penis, but only its glans is on the out side of the body, and it’s much smaller. Discharge – Liquid. Urine and semen are kinds of discharge, but the word is usually used to describe either the normal wetness of the vagina or the abnormal wetness that may come from an infection in the penis or vagina. Duct – Tube, the fallopian tubes may be called oviducts, because they are the path for an ovum. -

Gyn Oncology Colposcopy I. Basic Science/Mechanisms of Disease A

Gyn Oncology Colposcopy I. Basic Science/Mechanisms of Disease A. Genetics 1. Describe the clinical relevance of viral oncogenes. 2. Describe the role of aneuploidy in the pathogenesis of neoplasia. 3. Describe the inheritance patterns for malignancies of the pelvic organs and breast. 4. Describe the cell replication cycle, and identify the phases of the cycle most sensitive to radiation and chemotherapy. 5. Describe the genetic basis for tumor immunotherapy. B. Physiology 1. Describe the ability of vital organ systems to tolerate cancer therapy. 2. Describe the changes in cellular physiology that result from injury due to radiation and chemotherapy. 3. Describe the metabolic changes that occur in patients with a malignancy of the pelvic organs or breast. C. Embroyology 1. Describe the embryology of gonadal migration and its role in the pathogenesis of epithelial cell tumors. 2. Describe the pathogenesis of gonadal tumors in patients with gonadal dysgenesis. 3. Describe the embryologic precursors of ovarian germ cell tumors. D. Anatomy 1. Describe the gross histologic anatomy of the pelvic organs and breast. 2. Describe the vascular, lymphatic, and nerve supply to each of the pelvic organs. 3. Describe the anatomic relationship between the reproductive organs and other viscera, such as bladder, ureters, and bowel. 4. Describe the likely changes in the anatomic relationships of the pelvic and abdominal viscera created by surgical or radiation treatment for malignancy. E. Pharmacology 1. List major chemotherapeutic agents used for treatment of malignancies of the reproductive organs and breast. 2. Describe the principal adverse effects of the major chemotherapeutic agents. 3. Describe the medications of most value in treatment of complications resulting from chemotherapy and irradiation, such as: a. -

Physiology of Female Sexual Function and Dysfunction

International Journal of Impotence Research (2005) 17, S44–S51 & 2005 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0955-9930/05 $30.00 www.nature.com/ijir Physiology of female sexual function and dysfunction JR Berman1* 1Director Female Urology and Female Sexual Medicine, Rodeo Drive Women’s Health Center, Beverly Hills, California, USA Female sexual dysfunction is age-related, progressive, and highly prevalent, affecting 30–50% of American women. While there are emotional and relational elements to female sexual function and response, female sexual dysfunction can occur secondary to medical problems and have an organic basis. This paper addresses anatomy and physiology of normal female sexual function as well as the pathophysiology of female sexual dysfunction. Although the female sexual response is inherently difficult to evaluate in the clinical setting, a variety of instruments have been developed for assessing subjective measures of sexual arousal and function. Objective measurements used in conjunction with the subjective assessment help diagnose potential physiologic/organic abnormal- ities. Therapeutic options for the treatment of female sexual dysfunction, including hormonal, and pharmacological, are also addressed. International Journal of Impotence Research (2005) 17, S44–S51. doi:10.1038/sj.ijir.3901428 Keywords: female sexual dysfunction; anatomy; physiology; pathophysiology; evaluation; treatment Incidence of female sexual dysfunction updated the definitions and classifications based upon current research and clinical practice. -

Ovarian Cancer and Cervical Cancer

What Every Woman Should Know About Gynecologic Cancer R. Kevin Reynolds, MD The George W. Morley Professor & Chief, Division of Gyn Oncology University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI What is gynecologic cancer? Cancer is a disease where cells grow and spread without control. Gynecologic cancers begin in the female reproductive organs. The most common gynecologic cancers are endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer and cervical cancer. Less common gynecologic cancers involve vulva, Fallopian tube, uterine wall (sarcoma), vagina, and placenta (pregnancy tissue: molar pregnancy). Ovary Uterus Endometrium Cervix Vagina Vulva What causes endometrial cancer? Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic cancer: one out of every 40 women will develop endometrial cancer. It is caused by too much estrogen, a hormone normally present in women. The most common cause of the excess estrogen is being overweight: fat cells actually produce estrogen. Another cause of excess estrogen is medication such as tamoxifen (often prescribed for breast cancer treatment) or some forms of prescribed estrogen hormone therapy (unopposed estrogen). How is endometrial cancer detected? Almost all endometrial cancer is detected when a woman notices vaginal bleeding after her menopause or irregular bleeding before her menopause. If bleeding occurs, a woman should contact her doctor so that appropriate testing can be performed. This usually includes an endometrial biopsy, a brief, slightly crampy test, performed in the office. Fortunately, most endometrial cancers are detected before spread to other parts of the body occurs Is endometrial cancer treatable? Yes! Most women with endometrial cancer will undergo surgery including hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) in addition to removal of ovaries and lymph nodes. -

Echography of the Cervix and Uterus During the Proliferative and Secretory Phases of the Menstrual Cycle in Bonnet Monkeys (Macaca Radiata)

Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science Vol 53, No 1 Copyright 2014 January 2014 by the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science Pages 18–23 Echography of the Cervix and Uterus during the Proliferative and Secretory Phases of the Menstrual Cycle in Bonnet Monkeys (Macaca radiata) Uddhav K Chaudhari,1,* Siddnath M Metkari,2 Dhyananjay D Manjaramkar,2 Geetanjali Sachdeva,1 Rajendra Katkam,1 Atmaram H Bandivdekar,3 Abhishek Mahajan,4 Meenakshi H Thakur,4 and Sanjiv D Kholkute1 We undertook the present study to investigate the echographic characteristics of the uterus and cervix of female bonnet monkeys (Macaca radiata) during the proliferative and secretory phases of the menstrual cycle. The cervix was tortuous in shape and measured 2.74 ± 0.30 cm (mean ± SD) in width by 3.10 ± 0.32 cm in length. The cervical lumen contained 2 or 3 col- liculi, which projected from the cervical canal. The echogenicity of cervix varied during proliferative and secretory phases. The uterus was pyriform in shape (2.46 ± 0.28 cm × 1.45 ± 0.19 cm) and consisted of serosa, myometrium, and endometrium. The endometrium generated a triple-line pattern; the outer and central lines were hyperechogenic, whereas the inner line was hypoechogenic. The endometrium was significantly thicker during the secretory phase (0.69 ± 0.12 cm) than during the proliferative phase (0.43 ± 0.15 cm). Knowledge of the echogenic changes in the female reproductive organs of bonnet monkeys during a regular menstrual cycle may facilitate understanding of other physiologic and pathophysiologic changes. Ultrasound imaging is a noninvasive, atraumatic, and simple Materials and Methods method to assess various organs in humans and nonhuman pri- Animals and husbandry practices. -

2021 – the Following CPT Codes Are Approved for Billing Through Women’S Way

WHAT’S COVERED – 2021 Women’s Way CPT Code Medicare Part B Rate List Effective January 1, 2021 For questions, call the Women’s Way State Office 800-280-5512 or 701-328-2389 • CPT codes that are specifically not covered are 77061, 77062 and 87623 • Reimbursement for treatment services is not allowed. (See note on page 8). • CPT code 99201 has been removed from What’s Covered List • New CPT codes are in bold font. 2021 – The following CPT codes are approved for billing through Women’s Way. Description of Services CPT $ Rate Office Visits New patient; medically appropriate history/exam; straightforward decision making; 15-29 minutes 99202 72.19 New patient; medically appropriate history/exam; low level decision making; 30-44 minutes 99203 110.77 New patient; medically appropriate history/exam; moderate level decision making; 45-59 minutes 99204 165.36 New patient; medically appropriate history/exam; high level decision making; 60-74 minutes. 99205 218.21 Established patient; evaluation and management, may not require presence of physician; 99211 22.83 presenting problems are minimal Established patient; medically appropriate history/exam, straightforward decision making; 10-19 99212 55.88 minutes Established patient; medically appropriate history/exam, low level decision making; 20-29 minutes 99213 90.48 Established patient; medically appropriate history/exam, moderate level decision making; 30-39 99214 128.42 minutes Established patient; comprehensive history exam, high complex decision making; 40-54 minutes 99215 128.42 Initial comprehensive -

OBGYN Student Guide 2014.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS COMMON ABBREVIATIONS • 3 COMMON PRESCRIPTIONS • 4 OBSTETRICS • 5 What is a normal morning like on OB? • 5 What are good questions to ask a post-op/post-partum patient in the morning? • 6 How do I manage a post-partum patient? • 7 How should I organize and write my post-partum note? • 8 How do I present a patient on rounds? • 9 How do I evaluate a patient in triage/L&D? • 9 What are the most common complaints presented at triage/L&D? • 10 How should I organize and write my note for a triage H&P? • 12 What are the most common reasons people are admitted? • 13 How do I deliver a baby? • 13 What is my role as a student in a Cesarean section or tubal ligation procedure? • 15 How do I write up post-op orders? • 15 GYNECOLOGY/GYNECOLOGY ONCOLOGY • 17 What should I do to prepare for a GYN surgery? • 17 How do I manage a Gynecology/Gynecology Oncology patient? • 17 How should I organize and write my post-op GYN note? • 18 How do I write admit orders? • 19 What do routine post-op orders (Day #1) look like? • 19 What are the most common causes of post-operative fever? • 20 CLINIC • 21 What is my role as a student in clinic? • 21 What should I include in my prenatal clinic note? • 21 What should I include in my GYN clinic note? • 22 COMMON PIMP QUESTIONS • 23 2 COMMON ABBREVIATIONS 1°LTCS- primary low transverse cesarean LOF- leakage of fluid section NST- nonstress test AFI- amniotic fluid index NSVD- normal spontaneous vaginal delivery AROM- artificial rupture of membranes NT/NE- non-tender/non-engorged (breast BPP- biophysical -

Agreement Between Endocervical Brush and Endocervical Curettage in Patients Undergoing Repeat Endocervical Sampling

Agreement Between Endocervical Brush and Endocervical Curettage in Patients Undergoing Repeat Endocervical Sampling Meredith J. Alston MD David W. Doo MD Sara E. Mazzoni MD MPH Elaine H. Stickrath MD Denver Health Medical Center University of Colorado Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Background • Women with abnormal Pap tests referred for colposcopy frequently require sampling of the endocervix • ASCCP deems both the endocervical brush (ECB) and the endocervical currette (ECC) appropriate means of collecting endocervical samples (1) • Both have advantages and disadvantages, and it is unclear if one modality is superior Background • ECB has good sensitivity for endocervical lesions, it has poor specificity, ranging from 26- 38%2,3 • ECC has an excellent negative predictive value of 99.4% in women who had a satisfactory colposcopy • ECB is better tolerated by the patient, but runs the risk of contamination from the ectocervix • ECC is less likely to obtain an adequate sample Background • The results from the endocervical sample may influence clinical management after colposcopy. • Certain treatment options for high grade squamous intraepithelial neoplasia are available only to women with negative endocervical sampling. ▫ Ablative techniques ▫ Expectant management Background • Over concerns related to potential complications of excisional treatments, as well as over- treatment, there has been a push to re-introduce ablative techniques and, in appropriate clinical circumstances, expectant management, into the routine treatment of patients with cervical cancer precursors (12). Background • At our institution, it is our concern that due to the possibility of contamination from the ectocervix, a positive ECB may not represent a true positive endocervical sample. • We do not use a sleeve • Positive ECBs return for ECC if otherwise a candidate for ablative therapy or expectant management Objective • To describe the agreement between these two modalities of endocervical sampling. -

Oophorectomy Or Salpingectomy— Which Makes More Sense?

Oophorectomy or salpingectomy— which makes more sense? During hysterectomy for benign indications, many surgeons routinely remove the ovaries to prevent cancer. Here’s what we know about this practice. William H. Parker, MD CASE Patient opts for hysterectomy, asks than age 45 to prevent the subsequent devel- about oophorectomy opment of ovarian cancer (FIGURES 1 and 2). Your 46-year-old patient reports increasingly The 2002 Women’s Health Initiative re- severe dysmenorrhea at her annual visit, and a port suggested that exogenous hormone use pelvic examination reveals an enlarged uterus. was associated with a slight increase in the You order pelvic magnetic resonance imaging, risk of breast cancer.2 After its publication, which shows extensive adenomyosis. the rate of oophorectomy at the time of hys- After you counsel the patient about terectomy declined slightly, likely reflect- IN THIS her options, she elects to undergo lapa- ARTICLE ing women’s desire to preserve their own roscopic supracervical hysterectomy and source of estrogen.3 For women younger Algorithm: Should asks whether she should have her ovaries than age 50, further slight declines in the rate the ovaries removed at the time of surgery. She has no of oophorectomy were seen from 2002 to be removed? family history of ovarian or breast cancer. 2010. However, in the United States, almost page 54 What would you recommend for this 300,000 women still undergo “prophylactic” woman, based on her situation and current bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy every year.4 medical research? The lifetime risk of ovarian cancer Ovarian cancer does among women with a BRCA 1 mutation not come from the prophylactic procedure should be is 36% to 46%, and it is 10% to 27% among ovary considered only if 1) there is a rea- women with a BRCA 2 mutation. -

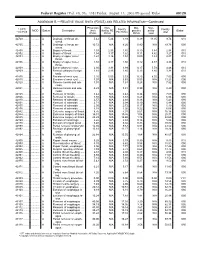

RELATIVE VALUE UNITS (RVUS) and RELATED INFORMATION—Continued

Federal Register / Vol. 68, No. 158 / Friday, August 15, 2003 / Proposed Rules 49129 ADDENDUM B.—RELATIVE VALUE UNITS (RVUS) AND RELATED INFORMATION—Continued Physician Non- Mal- Non- 1 CPT/ Facility Facility 2 MOD Status Description work facility PE practice acility Global HCPCS RVUs RVUs PE RVUs RVUs total total 42720 ....... ........... A Drainage of throat ab- 5.42 5.24 3.93 0.39 11.05 9.74 010 scess. 42725 ....... ........... A Drainage of throat ab- 10.72 N/A 8.26 0.80 N/A 19.78 090 scess. 42800 ....... ........... A Biopsy of throat ................ 1.39 2.35 1.45 0.10 3.84 2.94 010 42802 ....... ........... A Biopsy of throat ................ 1.54 3.17 1.62 0.11 4.82 3.27 010 42804 ....... ........... A Biopsy of upper nose/ 1.24 3.16 1.54 0.09 4.49 2.87 010 throat. 42806 ....... ........... A Biopsy of upper nose/ 1.58 3.17 1.66 0.12 4.87 3.36 010 throat. 42808 ....... ........... A Excise pharynx lesion ...... 2.30 3.31 1.99 0.17 5.78 4.46 010 42809 ....... ........... A Remove pharynx foreign 1.81 2.46 1.40 0.13 4.40 3.34 010 body. 42810 ....... ........... A Excision of neck cyst ........ 3.25 5.05 3.53 0.25 8.55 7.03 090 42815 ....... ........... A Excision of neck cyst ........ 7.07 N/A 5.63 0.53 N/A 13.23 090 42820 ....... ........... A Remove tonsils and ade- 3.91 N/A 3.63 0.28 N/A 7.82 090 noids. -

ICD-9-CM Procedure Version 23

GEM Documentation and Users Guide 2007 version Procedure Code Set General Equivalence Mappings ICD-10-PCS to ICD-9-CM and ICD-9-CM to ICD-10-PCS 2007 Version Documentation and User’s Guide Preface Purpose and Audience This document accompanies the 2007 update of the CMS public domain reference mappings of the ICD-10 Procedure Code System (ICD-10-PCS) and ICD-9-CM Volume 3. The purpose of this document is to give potential users the information they need to understand the structure and relationships contained in the mappings so they can use them correctly. The intended audience includes but is not limited to professionals working in health information, medical research and informatics. General interest readers may find section 1 useful. Those who may benefit from the material in both sections 1 and 2 include clinical and health information professionals who plan to directly use the mappings in their work. Software engineers and IT professionals interested in the details of the file format will find this information in Appendix A. In This Document For readability, ICD-9-CM is abbreviated “I-9,” and ICD-10-PCS is abbreviated “PCS.” The network of relationships between the two code sets described herein is called the General Equivalence Mappings (GEMs). • Section 1 is a general interest discussion of mapping as it pertains to the GEMs. It includes a discussion of the difficulties inherent in linking two coding systems of very different design and structure. The specific conventions and terms employed in the GEMs are discussed in more detail. • Section 2 contains detailed information on how to use the GEM files, for users who will be working hands-on with mapping applications now or in the future—as coding experts, researchers, claims processing personnel, software developers, etc. -

Hysterectomy with Bilateral Salpingo- Oophorectomy

Hysterectomy with Bilateral Salpingo- Oophorectomy Hysterectomy is a surgical procedure to remove all or part of the uterus*, and sometimes the ovaries* and/or fallopian tubes*; a gender-affirming, masculinizing lower surgery. Oophorectomy is a surgery to remove the ovaries*; a gender-affirming, masculinizing lower surgery. How is a hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo oophorectomy performed? 1. 3 to 5 tiny incisions are made on your abdomen. 2. Gas is put into your abdomen to inflate it. 3. A very small telescope is inserted in one of the incisions so the surgeon can see inside. 4. Long, narrow instruments are inserted through the incisions to detach the uterus*, fallopian tubes*, ovaries*, and cervix*. 5. These tissues are removed through the vagina*. 6. The top of the vagina* is closed with stitches that will dissolve over time. 7. The gas is released. Will I need to stay in the hospital? You will likely be discharged the same day as the surgery What medications will I be prescribed after surgery? You will likely receive painkillers and antibiotics to reduce the chance of infection. What should I expect after my procedure? • Discomfort in your belly • Pain in your upper chest and shoulder area, due to the gas used to inflate your abdomen. • Pink, brown or yellowish brown discharge from vagina* for 4 to 6 weeks • You may pass some stitches and this is normal • Incisions may be red with some bruising. This will slowly go away. • Incisions will be closed with steri-strips, sutures or staples. Your surgeon will let you know whether and how these will be removed.