Bıoenu V( Land Management in U›E5v›I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oregon Historic Trails Report Book (1998)

i ,' o () (\ ô OnBcox HrsroRrc Tnans Rpponr ô o o o. o o o o (--) -,J arJ-- ö o {" , ã. |¡ t I o t o I I r- L L L L L (- Presented by the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council L , May,I998 U (- Compiled by Karen Bassett, Jim Renner, and Joyce White. Copyright @ 1998 Oregon Trails Coordinating Council Salem, Oregon All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Oregon Historic Trails Report Table of Contents Executive summary 1 Project history 3 Introduction to Oregon's Historic Trails 7 Oregon's National Historic Trails 11 Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail I3 Oregon National Historic Trail. 27 Applegate National Historic Trail .41 Nez Perce National Historic Trail .63 Oregon's Historic Trails 75 Klamath Trail, 19th Century 17 Jedediah Smith Route, 1828 81 Nathaniel Wyeth Route, t83211834 99 Benjamin Bonneville Route, 1 833/1 834 .. 115 Ewing Young Route, 1834/1837 .. t29 V/hitman Mission Route, 184l-1847 . .. t4t Upper Columbia River Route, 1841-1851 .. 167 John Fremont Route, 1843 .. 183 Meek Cutoff, 1845 .. 199 Cutoff to the Barlow Road, 1848-1884 217 Free Emigrant Road, 1853 225 Santiam Wagon Road, 1865-1939 233 General recommendations . 241 Product development guidelines 243 Acknowledgements 241 Lewis & Clark OREGON National Historic Trail, 1804-1806 I I t . .....¡.. ,r la RivaÌ ï L (t ¡ ...--."f Pðiräldton r,i " 'f Route description I (_-- tt |". -

Impact Report

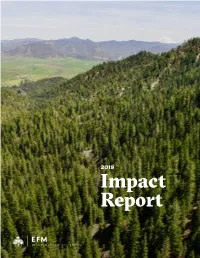

2019 Impact Report Natural springs, meadows and forested wetlands produce, filter, and store water for approximately 50% of communities in the western US that are dependent upon forested watersheds for water provision. Front Cover: The Scott River Headwaters property contains 40,000 acres of forests with the highest conifer diversity in the world, is a source of cold, clean water, and connects three wilderness areas to a rich agricultural valley below. EFM develops natural climate solutions that aim to generate positive environmental A Leading and social impacts, including carbon sequestration, habitat enhancement, and water quality protection while creating Impact investor value. EFM stewards over $200M of capital under management and advisement via commingled private funds and consulting Investment services. Investments are made through long-term fund vehicles that serve a diverse array of investors, including individuals, Manager family offices, foundations, and institutions. We specialize in blending public, private, and philanthropic capital in investment strategies that address multiple-stakeholder objectives and in managing investments for their full range of financial, ecological and social values. The Garibaldi forest is home to the first verified carbon project on private forestland in Oregon and Washington, which was developed by EFM in 2013 and expanded in 2019. These offsets are made possible by EFM’s management actions that extend rotations, expand reserves, retain trees in harvest units and protect important habitat. 1 Real -

OR Wild -Backmatter V2

208 OREGON WILD Afterword JIM CALLAHAN One final paragraph of advice: do not burn yourselves out. Be as I am — a reluctant enthusiast.... a part-time crusader, a half-hearted fanatic. Save the other half of your- selves and your lives for pleasure and adventure. It is not enough to fight for the land; it is even more important to enjoy it. While you can. While it is still here. So get out there and hunt and fish and mess around with your friends, ramble out yonder and explore the forests, climb the mountains, bag the peaks, run the rivers, breathe deep of that yet sweet and lucid air, sit quietly for awhile and contemplate the precious still- ness, the lovely mysterious and awesome space. Enjoy yourselves, keep your brain in your head and your head firmly attached to the body, the body active and alive and I promise you this much: I promise you this one sweet victory over our enemies, over those desk-bound men with their hearts in a safe-deposit box and their eyes hypnotized by desk calculators. I promise you this: you will outlive the bastards. —Edward Abbey1 Edward Abbey. Ed, take it from another Ed, not only can wilderness lovers outlive wilderness opponents, we can also defeat them. The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men (sic) UNIVERSITY, SHREVEPORT UNIVERSITY, to do nothing. MES SMITH NOEL COLLECTION, NOEL SMITH MES NOEL COLLECTION, MEMORIAL LIBRARY, LOUISIANA STATE LOUISIANA LIBRARY, MEMORIAL —Edmund Burke2 JA Edmund Burke. 1 Van matre, Steve and Bill Weiler. -

Or Wilderness-Like Areas, but Instead Declassified Previously Protected Wildlands with High Timber Value

48 OREGON WILD A Brief Political History of Oregon’s Wilderness Protections Government protection should be thrown around every wild grove and forest on the Although the Forest Service pioneered the concept of wilderness protection in the mountains, as it is around every private orchard, and trees in public parks. To say 1920s and 1930s, by the late 1940s and 1950s, it was methodically undoing whatever nothing of their values as fountains of timber, they are worth infinitely more than all good it had done earlier by declassifying administrative wilderness areas that contained the gardens and parks of town. any commercial timber. —John Muir1 Just prior to the end of its second term, and after receiving over a million public comments in support of protecting national forest roadless areas, the Clinton Administration promulgated a regulation (a.k.a. “the Roadless Rule”) to protect the Inadequacies of Administrative remaining unprotected wildlands (greater than 5,000 acres in size) in the National Forest System from road building and logging. At the time, Clinton’s Forest Service Protections chief Mike Dombeck asked rhetorically: here is “government protection,” and then there is government protection. Mere public ownership — especially if managed by the Bureau of Is it worth one-quarter of 1 percent of our nation’s timber supply or a fraction of a Land Management — affords land little real or permanent protection. fraction of our oil and gas to protect 58.5 million acres of wild and unfragmented land T National forests enjoy somewhat more protection than BLM lands, but in perpetuity?2 to fully protect, conserve and restore federal forests often requires a combination of Wilderness designation and additional appropriate congressional Dombeck’s remarks echoed those of a Forest Service scientist from an earlier era. -

Public Law 98-328-June 26, 1984

98 STAT. 272 PUBLIC LAW 98-328-JUNE 26, 1984 Public Law 98-328 98th Congress An Act June 26, 1984 To designate certain national forest system and other lands in the State of Oregon for inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System, and for other purposes. [H.R. 1149] Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the Oregon United States ofAmerica in Congress assembled, That this Act may Wilderness Act be referred to as the "Oregon Wilderness Act of 1984". of 1984. National SEc. 2. (a) The Congress finds that- Wilderness (1) many areas of undeveloped National Forest System land in Preservation the State of Oregon possess outstanding natural characteristics System. which give them high value as wilderness and will, if properly National Forest preserved, contribute as an enduring resource of wilderness for System. the ben~fit of the American people; (2) the Department of Agriculture's second roadless area review and evaluation (RARE II) of National Forest System lands in the State of Oregon and the related congressional review of such lands have identified areas which, on the basis of their landform, ecosystem, associated wildlife, and location, will help to fulfill the National Forest System's share of a quality National Wilderness Preservation System; and (3) the Department of Agriculture's second roadless area review and evaluation of National Forest System lands in the State of Oregon and the related congressional review of such lands have also identified areas which do not possess outstand ing wilderness attributes or which possess outstanding energy, mineral, timber, grazing, dispersed recreation and other values and which should not now be designated as components of the National Wilderness Preservation System but should be avail able for nonwilderness multiple uses under the land manage ment planning process and other applicable laws. -

Malheur Plan

Malheur River Subbasin Assessment and Management Plan For Fish and Wildlife Mitigation Appendix B: Program Inventory Malheur Watershed Council And Burns Paiute Tribe May, 2004 Prepared with assistance of: Watershed Professionals Network, LLC Malheur River Subbasin Assessment and Management Plan For Fish and Wildlife Mitigation Appendix B: Program Inventory 1 INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................... 1 2 INVENTORY OF EXISTING ACTIVITIES................................................................ 2 2.1 EXISTING LEGAL PROTECTION ........................................................................................................2 2.2 EXISTING PLANS ............................................................................................................................5 2.3 EXISTING MANAGEMENT PROGRAMS.............................................................................................12 2.4 EXISTING RESTORATION AND CONSERVATION PROJECTS...............................................................19 2.5 GAP ASSESSMENT OF EXISTING PROTECTIONS, PLANS, PROGRAMS AND PROJECTS.......................29 3 REFERENCES....................................................................................................... 33 4 APPENDIX B-1...................................................................................................... 34 List of Tables Table 1. Malheur River water quality targets and load allocations. ............................................. -

Molalla River-Table Rock Recreation Area Management Plan and Decision Record

Molalla River-Table Rock Recreation Area Management Plan and Decision Record Environmental Assessment Number: DOI-BLM-OR-S040-2010-0003-EA July 2011 United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management, Salem District Clackamas County, Oregon T6S-R3E, T7S-R3E, T7S-R4E, T7S R5E, Willamette Meridian Clackamas County, Oregon Responsible Agency: USDI - Bureau of Land Management Responsible Official: Cindy Enstrom, Field Manager Cascades Resource Area 1717 Fabry Road SE Salem, OR 97306 (503) 315-5969 For further information, contact: Zachary Jarrett, Project Lead Cascades Resource Area 1717 Fabry Road SE Salem, OR 97306 (503) 375-5610 As the Nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering wisest use of our land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The Department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to assure that their development is in the best interest of all our people. The Department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in Island Territories under U.S. administration. BLM/OR/WA/AE-11/021+1792 Molalla River-Table Rock Recreation Area Management Plan and DR July 2011 2 Table of Contents Interdisciplinary Team of Preparers ............................................................................................... -

The Siskiyou Hiker 2020

WINTER 2020 THE SISKIYOU HIKER Outdoor news from the Siskiyou backcountry SPECIAL ISSUE: 2020 Stewardship Report Photo by: Trevor Meyer SEASON UPDATES ALL THE TRAILS CLEARED THIS YEAR LOOKING AHEAD CHECK OUT OUR Laina Rose, 2020 Crew Leader PLANS FOR 2021 LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR Winter, 2020 Dear Friends, In this special issue of the Siskiyou Hiker, we’ve taken our annual stewardship report and wrapped it up into a periodical for your review. Like everyone, 2020 has been a tough year for us. But I hope this issue illustrates that this year was a challenge we were up for. We had to make big changes, including a hiring freeze on interns and seasonals. My staff, board, our volun- teers, and I all had to flex into what roles needed to be filled, and far-ahead planning became almost impossi- ble. But we were able to wrap up technical frontcountry projects in the spring, and finished work on the Briggs Creek Bridge and a long retaining wall on the multi-use Taylor Creek Trail. Then my staff planned for a smaller intern program that was stronger beyond measure. We put practices in place to keep everyone safe, and got through the year intact and in good health. This year we had a greater impact on the lives of the young people who serve on our Wilderness Conserva- tion Corps. They completed media projects and gained technical skills. Everyone pushed themselves and we took the first real steps in realizing greater diversity throughout our organization. And despite protocols in place to slow the spread of Covid-19, we actually grew our volunteer program. -

Table 7 - National Wilderness Areas by State

Table 7 - National Wilderness Areas by State * Unit is in two or more States ** Acres estimated pending final boundary determination + Special Area that is part of a proclaimed National Forest State National Wilderness Area NFS Other Total Unit Name Acreage Acreage Acreage Alabama Cheaha Wilderness Talladega National Forest 7,400 0 7,400 Dugger Mountain Wilderness** Talladega National Forest 9,048 0 9,048 Sipsey Wilderness William B. Bankhead National Forest 25,770 83 25,853 Alabama Totals 42,218 83 42,301 Alaska Chuck River Wilderness 74,876 520 75,396 Coronation Island Wilderness Tongass National Forest 19,118 0 19,118 Endicott River Wilderness Tongass National Forest 98,396 0 98,396 Karta River Wilderness Tongass National Forest 39,917 7 39,924 Kootznoowoo Wilderness Tongass National Forest 979,079 21,741 1,000,820 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 654 654 Kuiu Wilderness Tongass National Forest 60,183 15 60,198 Maurille Islands Wilderness Tongass National Forest 4,814 0 4,814 Misty Fiords National Monument Wilderness Tongass National Forest 2,144,010 235 2,144,245 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 15 15 Petersburg Creek-Duncan Salt Chuck Wilderness Tongass National Forest 46,758 0 46,758 Pleasant/Lemusurier/Inian Islands Wilderness Tongass National Forest 23,083 41 23,124 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 15 15 Russell Fjord Wilderness Tongass National Forest 348,626 63 348,689 South Baranof Wilderness Tongass National Forest 315,833 0 315,833 South Etolin Wilderness Tongass National Forest 82,593 834 83,427 Refresh Date: 10/14/2017 -

Eg-Or-Index-170722.05.Pdf

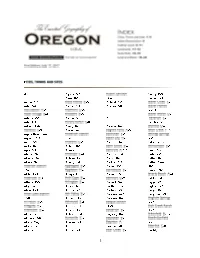

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Burns Paiute Tribal Reservation G-6 Siletz Reservation B-4 Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Reservation B-3 Umatilla Indian Reservation G-2 Fort McDermitt Indian Reservation H-9,10 Warm Springs Indian Reservation D-3,4 Ankeny National Wildlife Refuge B-4 Basket Slough National Wildlife Refuge B-4 Badger Creek Wilderness D-3 Bear Valley National Wildlife Refuge D-9 9 Menagerie Wilderness C-5 Middle Santiam Wilderness C-4 Mill Creek Wilderness E-4,5 Black Canyon Wilderness F-5 Monument Rock Wilderness G-5 Boulder Creek Wilderness C-7 Mount Hood National Forest C-4 to D-2 Bridge Creek Wilderness E-5 Mount Hood Wilderness D-3 Bull of the Woods Wilderness C,D-4 Mount Jefferson Wilderness D-4,5 Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument C-9,10 Mount Thielsen Wilderness C,D-7 Clackamas Wilderness C-3 to D-4 Mount Washington Wilderness D-5 Cold Springs National Wildlife Refuge F-2 Mountain Lakes Wilderness C-9 Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area Newberry National Volcanic Monument D-6 C-2 to E-2 North Fork John Day Wilderness G-3,4 Columbia White Tailed Deer National Wildlife North Fork Umatilla Wilderness G-2 Refuge B-1 Ochoco National Forest E-4 to F-6 Copper Salmon Wilderness A-8 Olallie Scenic Area D-4 Crater Lake National Park C-7,8 Opal Creek Scenic Recreation Area C-4 Crooked River National Grassland D-4 to E-5 Opal Creek Wilderness C-4 Cummins Creek Wilderness A,B-5 Oregon Badlands Wilderness D-5 to E-6 Deschutes National Forest C-7 to D-4 Oregon Cascades Recreation Area C,D-7 Diamond Craters Natural Area F-7 to G-8 Oregon -

Oregon Caves Domain of the Cavemen

Oregon Caves NM: Historic Resource Study OREGON CAVES Domain of the Cavemen: A Historic Resource Study of Oregon Caves National Monument DOMAIN OF THE CAVEMEN A Historic Resource Study of Oregon Caves National Monument by Stephen R. Mark Historian 2006 National Park Service Pacific West Region TABLE OF CONTENTS orca/hrs/index.htm Last Updated: 06-Mar-2007 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/orca/hrs/index.htm[10/30/2013 3:19:32 PM] Oregon Caves NM: Historic Resource Study (Table of Contents) OREGON CAVES Domain of the Cavemen: A Historic Resource Study of Oregon Caves National Monument TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover (HTML) Cover (PDF) Preface (PDF) Acknowledgments (PDF) Introduction: The Marble Halls of Oregon (PDF) 1: Locked in a Colonial Hinterland, 1851-1884 (PDF) Exploration and westward expansion Cultural collision and its consequences Social and economic transition Discovery of the Oregon Caves 2: The Closing of a Frontier, 1885-1915 (PDF) Developing a "private" show cave Into a void The advent of federal land management 3: Boosterism's Public-Private Partnership, 1816-1933 (PDF) Highways to Oregon Caves Beginnings of a recreational infrastructure Transfer to the National Park Service 4: Improving a Little Landscape Garden, 1934-1943 (PDF) New Lights, but an old script Camp Oregon Caves, NM-1 Development of Grayback Campground CCC projects at Oregon Caves Expanded concession facilities NPS master plans for Oregon Caves Other vehicles for shaping visitor experience 5: Decline from Rustic Ideal, 1944-1995 (PDF) Postwar park development -

Draft North Cascade 2012 Implementation Plan

North Cascade District Implementation Plan June 2012 Table of Contents Page Introduction ____________________________________________________________ 1 District Overview ________________________________________________________ 3 Land Ownership ______________________________________________________ 3 Forest Land Management Classification ____________________________________ 3 Background ________________________________________________________ 3 Major Change to FLMCS _____________________________________________ 4 Current Condition _____________________________________________________ 6 History ___________________________________________________________ 6 Physical Elements _____________________________________________________ 7 Geology and Soils ___________________________________________________ 7 Topography ________________________________________________________ 9 Water ____________________________________________________________ 9 Climate ___________________________________________________________ 9 Natural Disturbance _________________________________________________ 9 Biological Elements __________________________________________________ 10 Vegetation ________________________________________________________ 10 Forest Health _____________________________________________________ 11 Fish and Wildlife __________________________________________________ 11 Human Uses ________________________________________________________ 16 Forest Management ________________________________________________ 16 Roads ___________________________________________________________